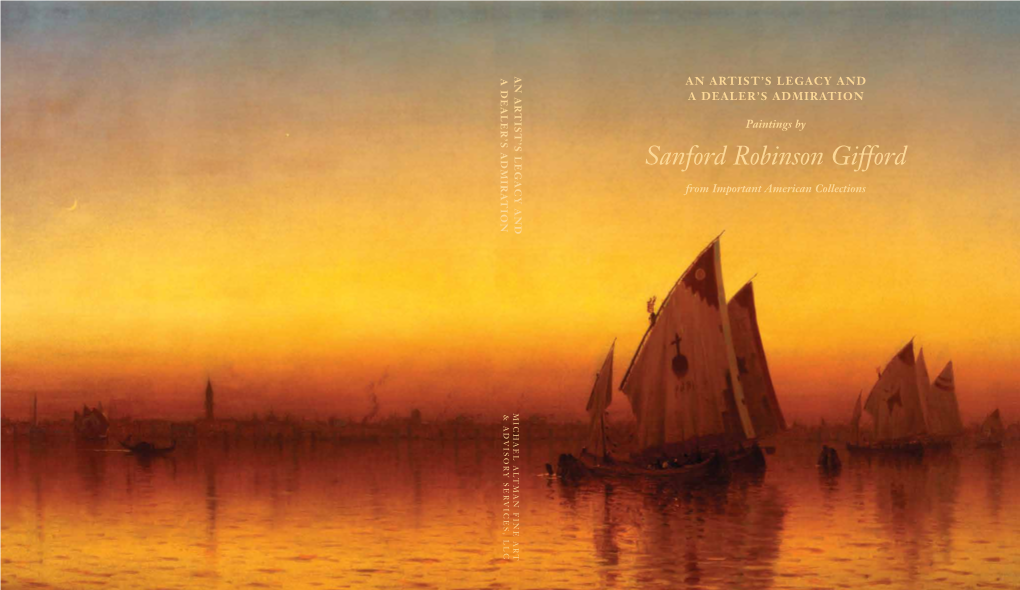

Sanford Robinson Gifford

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hudson River School

Hudson River School 1796 1800 1801 1805 1810 Asher 1811 Brown 1815 1816 Durand 1820 Thomas 1820 1821 Cole 1823 1823 1825 John 1826 Frederick 1827 1827 1827 1830 Kensett 1830 Robert 1835 John S Sanford William Duncanson David 1840 Gifford Casilear Johnson Jasper 1845 1848 Francis Frederic Thomas 1850 Cropsey Edwin Moran Worthington Church Thomas 1855 Whittredge Hill 1860 Albert 1865 Bierstadt 1870 1872 1875 1872 1880 1880 1885 1886 1910 1890 1893 1908 1900 1900 1908 1908 1902 Compiled by Malcolm A Moore Ph.D. IM Rocky Cliff (1857) Reynolds House Museum of American Art The Beeches (1845) Metropolitan Museum of Art Asher Brown Durand (1796-1886) Kindred Spirits (1862) Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art The Fountain of Vaucluse (1841) Dallas Museum of Art View from Mount Holyoke, Northampton, Massachusetts, after a Thunderstorm - the Oxbow. (1836) Metropolitan Museum of Art Thomas Cole (1801-48) Distant View of Niagara Falls (1836) Art Institute of Chicago Temple of Segesta with the Artist Sketching (1836) Museum of Fine Arts, Boston John William Casilear (1811-1893) John Frederick Kensett (1816-72) Lake George (1857) Metropolitan Museum of Art View of the Beach at Beverly, Massachusetts (1869) Santa Barbara Museum of Art David Johnson (1827-1908) Natural Bridge, Virginia (1860) Reynolda House Museum of American Art Lake George (1869) Metropolitan Museum of Art Worthington Whittredge (1820-1910) Jasper Francis Cropsey (1823-1900) Indian Encampment (1870-76) Terra Foundation for American Art Starrucca Viaduct, Pennsylvania (1865) Toledo Museum of Art Sanford Robinson Gifford (1823-1880) Robert S Duncanson (1821-1902) Whiteface Mountain from Lake Placid (1866) Smithsonian American Art Museum On the St. -

American Art & Pennsylvania Impressionists (1619) Lot 29

American Art & Pennsylvania Impressionists (1619) December 9, 2018 EDT Lot 29 Estimate: $20000 - $30000 (plus Buyer's Premium) GEORGE INNESS (AMERICAN 1825-1894) "SIASCONSET BEACH" (NANTUCKET ISLAND) Signed and dated 'G. Inness 1883' bottom right, oil on canvas 18 x 26 in. (45.7 x 66cm) Provenance: The Artist. The Estate of the Artist. Fifth Avenue Art Galleries, New York, New York, sale of February 12-14, 1895, no. 39 (as "Siasconset"). Acquired directly from the above sale. Collection of Edward Thaw, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. His wife, Mrs. Edward Thaw, Dublin, New Hampshire. The Old Print Shop Inc., New York, New York, 1947. Collection of Mrs. Lucius D. Potter, Greenfield, Massachusetts. Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Walter Beinecke, Jr., Port Clyde, Maine. Joseph Murphy Auction, Kennebunkport, Maine, sale of October 1994, no. 62. Acquired directly from the above sale. Richardson-Clarke Gallery, Boston, Massachusetts; jointly with Vose Galleries, Boston, Massachusetts. Acquired directly from the above. Collection of Richard M. Scaife, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. EXHIBITED: "Exhibition of the Paintings Left by the Late George Inness," American Fine Art Society, New York, New York, December 27, 1894, no. 197. LITERATURE: LeRoy Ireland, The Works of George Inness,Austin, Texas: University of Texas Press, 1965, p. 274, no. 1105 (illustrated as "Shore at Siasconset, Nantucket Island, Mass."). Robert A. diCurio, Art on Nantucket, Nantucket: Nantucket Historical Association, 1982, p. 187 (illustrated as 'Siasconset Beach." p. 188. ) Vose Art Notes 4, Vose Galleries, Boston, Massachusetts, Winter 1995, no. 3 (illustrated). Michael Quick, George Inness: A Catalogue Raisonné,New Brunswick, New Jersey and London, United Kingdom: Rutgers University Press, volume II, no. -

SURROUNDED by NATURE by Kathleen Mcmillen

SURROUNDED BY NATURE by Kathleen McMillen Stephen Pentak paints nature at its most alluring and enticing. Cal moving water, his universal images are both peaceful and challeng A painter of endangered places, Pentak is also a dedicated catch- time visiting pristine places where trout live. While observing the w experience of being surrounded by nature and often takes photogr with artist Joseph Albers—whose angular shapes balanced with co “Art is not an object, it is an experience.” Pentak was born in Denver, and spent his youth in upstate New Yo Hudson River Valley and the Adirondack Mountains. During this pe meditative and a life-long learning experience. His first exposure to Thomas Cole, Frederic Church, Albert Bierstadt, George Inness an Having set aside traditional brushes and pallet knives, Pentak use brushes to achieve the surface he prefers. He paints on birch pane stable surface for him to work on. He begins by applying layers an crimson, violet, and finally blue or green. Each step either covers o reflections and glare on the surfaces. The various layers of paint a framed. After all, those raw edges reveal the process. “I started out doing more conceptual, nonobjective minimalist paint my interest in the outdoors evolved into my work. I sort of let it in th flop painter,” Pentak says, “I see my paintings in two ways. There’s landscape, you know it has representations of the observable worl you never forget that you are looking at paint on panel applied with compositional structure. The duality takes you back and forth betw 2005, VII.VIII Two Birches Variant, 48 x 30 Oil on panel made with paint.” Pentak initially studied engineering and worked part-time as a surv lost his eye for seeing the land in geometric grids, which is still evi strong, horizontal plane of the water and then breaks the placidity creates a tension that resolves itself, like breathing in and out—inh Despite limited subject matter, none of Pentak’s paintings is like an same subject. -

Life, Art, and Letters of George Inness

LIFE, ART AND LETTERS OF GEORGE INNE.5S GEORGE INNESSJr. «*« <.-:..; : vM ( > EX LIBRIS '< WHITNEY MUSEUM OF AMERICAN ART 10WEST 8TH STREET-NEW YORK jfn LIFE, ART, AND LETTERS OF GEORGE INNESS Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2012 with funding from Metropolitan New York Library Council - METRO http://archive.org/details/lifelettersOOinne GEORGE INNBSS (Painted by George Inness, Jr.) LIFE, ART, AND LITTERS OF GEORGE INNESS BY GEORGE INNESS, Jr. ILLUSTRATED WITH PORTRAITS AND MANY REPRODUCTIONS OF PAINTINGS WITH AN INTRODUCTION BY ELLIOTT DAINGERFIELD NEW YORK THE CENTURY CO. 1917 Copyright, 1917, by The Centuky Co. Published, October, 1917 I DEDICATE THIS BOOK TO MY DEAR WIFE JULIA GOODRICH INNESS WHO HAS FILLED MY LIFE WITH HAPPINESS AND WHOSE HELP AND COUNSEL HAVE MADE THIS WORK POSSIBLE PREFACE What I would like to give you is George Inness; as he was, as lie talked, as he lived—not what I saw in him or how I interpreted him, but him—and hav- ing given you all I can remember of what he said and did I want you to form your own opinion. My story shall be a simple rendering of facts—as I remember them ; in other words, I will put the pig- ment on the canvas and leave it to you to form the picture. George Inness, Jr. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I wish to acknowledge the courtesy of the follow- ing persons and institutions who have been of great assistance in furnishing me with the material for this book: Mrs. J. Scott Hartley, Mr. James W. Ells- worth, Mr. Thomas B. -

The Charles Hosmer Morse Museum of American Art Receives the Extraordinary American Art Collection of Theodore E

March 9, 2021 CONTACT: FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Emily Sujka Cell: (407) 907-4021 Office: (407) 645-5311, ext. 109 [email protected] The Charles Hosmer Morse Museum of American Art Receives the Extraordinary American Art Collection of Theodore E. Stebbins Jr. and Susan Cragg Stebbins Note to Editors: Attached is a high-resolution image of Theodore E. Stebbins Jr. and Susan Cragg Stebbins. Images of several paintings in the gift are available via this Dropbox link: https://www.dropbox.com/sh/7d3r2vyp4nyftmi/AABg2el2ZCP180SIEX2GTcFTa?dl=0. WINTER PARK, FL—Theodore E. Stebbins Jr. and Susan Cragg Stebbins have given their outstanding collection of American art to The Charles Hosmer Morse Museum of American Art in Winter Park, Florida. The couple have made their gift in honor of Mrs. Stebbins’s parents, Evelyn and Henry Cragg, longtime residents of Winter Park. Mr. Cragg was a member of the Charles Homer Morse Foundation board of trustees from its founding in 1976 until his death in 1988. It is impossible to think about American art scholarship, museum culture, and collecting without the name Theodore Stebbins coming to mind. Stebbins has had an illustrious career as a professor of art history and as curator at the Yale University Art Gallery (1968–77), the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (1977–2000), and the Harvard Art Museums (2001–14). Many of Stebbins’s former students occupy positions of importance throughout the art world. Among his numerous publications are his broad survey of American works on paper, American Master Drawings and Watercolors: A History of Works on Paper from Colonial Times to the Present (1976), and his definitive works on American painter Martin Johnson Heade (1819–1904) including the Life and Work of Martin Johnson Heade (2000). -

Lackawanna Valley

MAN and the NATURAL WORLD: ROMANTICISM (Nineteenth-Century American Landscape Painting) NINETEENTH-CENTURY AMERICAN LANDSCAPE PAINTING Online Links: Thomas Cole – Wikipedia Hudson River School – Wikipedia Frederic Edwin Church – Wikipedia Cole's Oxbow – Smarthistory Cole's Oxbow (Video) – Smarthistory Church's Niagara and Heart of the Andes - Smarthistory Thomas Cole. The Oxbow (View from Mount Holyoke, Northampton, Massachusetts, after a Thunderstorm), 1836, oil on canvas Thomas Cole (1801-1848) was one of the first great professional landscape painters in the United States. Cole emigrated from England at age 17 and by 1820 was working as an itinerant portrait painter. With the help of a patron, he traveled to Europe between 1829 and 1832, and upon his return to the United States he settled in New York and became a successful landscape painter. He frequently worked from observation when making sketches for his paintings. In fact, his self-portrait is tucked into the foreground of The Oxbow, where he stands turning back to look at us while pausing from his work. He is executing an oil sketch on a portable easel, but like most landscape painters of his generation, he produced his large finished works in the studio during the winter months. Cole painted this work in the mid- 1830s for exhibition at the National Academy of Design in New York. He considered it one of his “view” paintings because it represents a specific place and time. Although most of his other view paintings were small, this one is monumentally large, probably because it was created for exhibition at the National Academy. -

George Inness in the 1860S

“The Fact of the Indefinable”: George Inness in the 1860s Adrienne Baxter Bell, Ph.D. Professor of Art History Marymount Manhattan College Swedenborg and the Arts Conference 7 June 2017 George Inness, Clearing Up, 1860, oil on canvas, George Walter Vincent Smith Art Museum, Springfield, Mass. George Inness, A Winter Sky, 1866, oil on canvas, Cleveland Museum of Art Sunset George Inness, On the Delaware River, 1861-1863, George Inness, , 1860-65, oil on canvas, Brooklyn Museum oil on canvas, private collection Above right: George Inness, Christmas Eve (Winter Moonlight), 1866, Montclair Art Museum Below right: George Inness, A Winter Sky, 1866, Cleveland Museum of Art Below: George Inness, Peace and Plenty, 1865, oil on canvas, Metropolitan Museum of Art Thomas Moran, Mountain of the Holy Cross,1875, Thomas Cole, The Subsiding of the Waters of the Deluge, 1829, Smithsonian American Art Museum oil on canvas, Autry Museum of the American West, Los Angeles Ralph Waldo Emerson (left), Emanuel Swedenborg (center), George Inness (right) William Page, Self-Portrait, Mathew Brady, George Inness, Inness’s house (above) at 1860-61, oil on canvas, 1862, photograph Eagleswood Military Academy (below) Detroit Institute of the Arts George Inness, The Valley of the Shadow of Death, 1867, oil on canvas, Frances Lehman Loeb Art Gallery, Vassar College LEFT: The Jewish poet Süßkind von Trimberg (ca. 1230-1300) at right, Codex Manesse, 1304-1340, Heidelberg University Library BELOW: Marc Chagall, The Praying Jew (Rabbi of Vitebsk), 1914, oil on canvas, Art Institute of Chicago George Inness, The Valley of the Shadow of Death, 1867, oil on canvas, Frances Lehman Loeb Art Gallery, Vassar College George Inness, A June Day, 1881, oil on canvas, J.M.W. -

A Call to the Wild

Q UESTROYAL F INE A RT, LLC A Call to the Wild Thomas Moran John Frederick Kensett Evening Clouds, 1902 New England Coastal Scene with Figures, 1864 Oil on canvas Oil on canvas 141/8 x 20 inches 141/4 x 243/16 inches Monogrammed, inscribed, and dated Monogrammed and dated lower right: JF.K. / ’64. lower left: TMORAN / N.A. / 1902” March 8 – 30, 2019 An Exhibition and Sale A Call to the Wild Louis M. Salerno, Owner Brent L. Salerno, Co-Owner Chloe Heins, Director Nina Sangimino, Assistant Director Ally Chapel, Senior Administrator Megan Gatton, Gallery Coordinator Pavla Berghen-Wolf, Research Associate Will Asencio, Art Handler Rita J. Walker, Controller Photography by Timothy Pyle, Light Blue Studio and Ally Chapel Q UESTROYAL F INE A RT, LLC 903 Park Avenue (at 79th Street), Third Floor, New York, NY 10075 :(212) 744-3586 :(212) 585-3828 : Monday–Friday 10–6, Saturday 10–5 and by appointment : gallery@questroyalfineart.com www.questroyalfineart.com A Call to the Wild Those of us who acquire Hudson River School paintings will of composition, in the application of brushstroke, in texture, in possess something more than great works of art. Each is a perspective, in tone and color, each artist creates a unique visual glimpse of our native land, untouched by man. These paintings language. They have left us a painted poetry that required a compel us to contemplate, they draw us beyond the boundaries combination of imagination and extraordinary technical ability. of a time and space that define our present lives so that we may The magnitude of the artistic achievement of this first American consider eternal truths. -

The Hudson River School at the New-York Historical Society: Nature and the American Vision

The Hudson River School at the New-York Historical Society: Nature and the American Vision Marie-François-Régis Gignoux (1814–1882) Mammoth Cave, Kentucky , ca. 1843 Oil on canvas Gift of an Anonymous Donor, X.21 After training at the French École des Beaux-Arts , Gignoux immigrated to the United States, where he soon established himself as a landscape specialist. He was drawn to a vast underground system of corridors and chambers in Kentucky known as Mammoth Cave. The site portrayed has been identified as the Rotunda—so named because its grand, uninterrupted interior space recalls that of the Pantheon in Rome. Gignoux created a romantic image rooted in fact and emotion. In contrast to the bright daylight glimpsed through the cavern mouth, the blazing fire impresses a hellish vision that contemporaneous viewers may have associated with the manufacture of gunpowder made from the bat guano harvested and rendered in vats in that very space since the War of 1812. William Trost Richards (1833–1905) June Woods (Germantown) , 1864 Oil on linen The Robert L. Stuart Collection, S–127 Richards followed the stylistic trajectory of the Hudson River School early in his career, except for a brief time in the early 1860s, when he altered his technique and compositional approach in response to the Pre-Raphaelite aesthetics of the English critic John Ruskin. Ruskin’s call for absolute fidelity to nature manifested itself in the United States in a radical 1 group of artists who formed the membership of the Association for the Advancement of Truth in Art, to which Richards was elected in 1863. -

NINETEENTH CENTURY AMERICAN PAINTINGS at BOWDOIN COLLEGE Digitized by the Internet Archive

V NINETEENTH CENTURY^ AMERIGAN PAINTINGS AT BOWDOIN COLLEGE NINETEENTH CENTURY AMERICAN PAINTINGS AT BOWDOIN COLLEGE Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2015 https://archive.org/details/nineteenthcenturOObowd_0 NINETEENTH CENTURY AMERICAN PAINTINGS AT BOWDOIN COLLEGE BOWDOIN COLLEGE MUSEUM OF ART 1974 Copyright 1974 by The President and Trustees of Bowdoin College This Project is Supported by a Grant from The National Endowment for The Arts in Washington, D.C. A Federal Agency Catalogue Designed by David Berreth Printed by The Brunswick Publishing Co. Brunswick, Maine FOREWORD This catalogue and the exhibition Nineteenth Century American Paintings at Bowdoin College begin a new chapter in the development of the Bow- doin College Museum of Art. For many years, the Colonial and Federal portraits have hung in the Bowdoin Gallery as a permanent exhibition. It is now time to recognize that nineteenth century American art has come into its own. Thus, the Walker Gallery, named in honor of the donor of the Museum building in 1892, will house the permanent exhi- bition of nineteenth century American art; a fitting tribute to the Misses Walker, whose collection forms the basis of the nineteenth century works at the College. When renovations are complete, the Bowdoin and Boyd Galleries will be refurbished to house permanent installations similar to the Walker Gal- lery's. During the renovations, the nineteenth century collection will tour in various other museiniis before it takes its permanent home. My special thanks and congratulations go to David S. Berreth, who developed the original idea for the exhibition to its present conclusion. His talent for exhibition installation and ability to organize catalogue materials will be apparent to all. -

Geology and Ecology in the Nineteenth Century American Landscape Paintings of Frederic E

Curriculum Units by Fellows of the Yale-New Haven Teachers Institute 2001 Volume II: Art as Evidence: The Interpretation of Objects Reading the Landscape: Geology and Ecology in the Nineteenth Century American Landscape Paintings of Frederic E. Church Curriculum Unit 01.02.01 by Stephen P. Broker Introduction This curriculum unit uses nineteenth century American landscape paintings to teach high school students about topics in geography, geology, ecology, and environmental science. The unit blends subject matter from art and science, two strongly interconnected and fully complementary disciplines, to enhance learning about the natural world and the interaction of humans in natural systems. It is for use in The Dynamic Earth (An Introduction to Physical and Historical Geology), Environmental Science, and Advanced Placement Environmental Science, courses I teach currently at Wilbur Cross High School. Each of these courses is an upper level (Level 1 or Level 2) science elective, taken by high school juniors and seniors. Because of heavy emphasis on outdoor field and laboratory activities, each course is limited in enrollment to eighteen students. The unit has been developed through my participation in the 2001 Yale-New Haven Teachers Institute seminar, "Art as Evidence: The Interpretation of Objects," seminar leader Jules D. Prown (Yale University, Professor of the History of Art, Emeritus). The "objects" I use in developing unit activities include posters or slides of studio landscape paintings produced by Frederic Church (1826-1900), America's preeminent landscape painter of the nineteenth century, completed during his highly productive years of the 1840s through the 1860s. Three of Church's oil paintings referred to may also be viewed in nearby Connecticut or New York City art museums. -

JERVIS MCENTEE (American, 1828-1891) Vermont Sugaring Oil on Canvas 20 X 30 Inches (50.8 X 76.2 Cm) Signed Lower Right: Mce N.A

JERVIS MCENTEE (American, 1828-1891) Vermont Sugaring Oil on canvas 20 x 30 inches (50.8 x 76.2 cm) Signed lower right: McE_N.A. PROVENANCE: Barridoff Galleries, Portland, Maine, American and European Art, August 6, 1997, lot 179. Jervis McEntee was born in the Hudson River Valley, in Rondout, New York, in 1828. At the age of twenty-two, McEntee studied for a year with Hudson River School master, Frederic E. Church, in New York City. He then worked briefly in the flour and feed business, before deciding, in 1855, to devote himself entirely to painting. He took up a studio at the legendary Tenth Street Studio Building, where artists such as Winslow Homer, Albert Bierstadt, and Church himself worked and exhibited. In 1858, McEntee had an additional studio built next to his father's home in Rondout, where the artist spent many summers painting the nearby Catskill Mountains. He was elected an associate member of the National Academy in 1860, and became a full member the following year. During the Civil War, he fought with the Union Army. McEntee's belief in the capacity of the natural landscape to arouse profound emotions often inspired him to exhibit his paintings with passages of poetry, reflecting the influence of the poet Henry Pickering (1781-1838) who boarded with the McEntee family during the artist's childhood and introduced the young boy to fine art, poetry, and literature. During his lifetime, McEntee's work was shown at such venues as the National Academy of Design, the Brooklyn Art Association, the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, the Boston Art Club, the Boston Athenaeum, the Art Institute of Chicago, the Royal Academy in London, and the Paris Exposition of 1867.