The Physical, Emotional, and Behavioural Effects of High-Density Crowding on Mumbai’S Suburban Rail Passengers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Understanding Users' Satisfaction Towards Public Transit System In

International Journal of Geo-Information Article Understanding Users’ Satisfaction Towards Public Transit System in India: A Case-Study of Mumbai Rahul Deb Das 1,2 1 Department of Geography, University of Zurich, CH-8006 Zurich, Switzerland; [email protected] or [email protected] 2 IBM, Mies-van-der-Rohe-Strasse 6, 80807 Munich, Germany Abstract: In this work, we present a novel approach to understand the quality of public transit system in resource constrained regions using user-generated contents. With growing urban population, it is getting difficult to manage travel demand in an effective way. This problem is more prevalent in developing cities due to lack of budget and proper surveillance system. Due to resource constraints, developing cities have limited infrastructure to monitor transport services. To improve the quality and patronage of public transit system, authorities often use manual travel surveys. But manual surveys often suffer from quality issues. For example, respondents may not provide all the detailed travel information in a manual travel survey. The survey may have sampling bias. Due to close-ended design (specific questions in the questionnaire), lots of relevant information may not be captured in a manual survey process. To address these issues, we investigated if user-generated contents, for example, Twitter data, can be used to understand service quality in Greater Mumbai in India, which can complement existing manual survey process. To do this, we assumed that, if a tweet is relevant to public transport system and contains negative sentiment, then that tweet expresses user’s dissatisfaction towards the public transport service. -

India 2020 Crime & Safety Report: Mumbai

India 2020 Crime & Safety Report: Mumbai This is an annual report produced in conjunction with the Regional Security Office at the U.S. Consulate General in Mumbai. OSAC encourages travelers to use this report to gain baseline knowledge of security conditions in India. For more in-depth information, review OSAC’s India-specific webpage for original OSAC reporting, consular messages, and contact information, some of which may be available only to private-sector representatives with an OSAC password. Travel Advisory The current U.S. Department of State Travel Advisory at the date of this report’s publication assesses most of India at Level 2, indicating travelers should exercise increased caution due to crime and terrorism. Some areas have increased risk: do not travel to the state of Jammu and Kashmir (except the eastern Ladakh region and its capital, Leh) due to terrorism and civil unrest; and do not travel to within ten kilometers of the border with Pakistan due to the potential for armed conflict. Review OSAC’s report, Understanding the Consular Travel Advisory System Overall Crime and Safety Situation The Consulate represents the United States in Western India, including the states of Maharashtra, Gujarat, Madhya Pradesh, Chhattisgarh, and Goa. Crime Threats The U.S. Department of State has assessed Mumbai as being a MEDIUM-threat location for crime directed at or affecting official U.S. government. Although it is a city with an estimated population of more than 25 million people, Mumbai remains relatively safe for expatriates. Being involved in a traffic accident remains more probable than being a victim of a crime, provided you practice good personal security. -

Transport in India Transport in the Republic of India Is an Important

Transport in India Transport in the Republic of India is an important part of the nation's economy. Since theeconomic liberalisation of the 1990s, development of infrastructure within the country has progressed at a rapid pace, and today there is a wide variety of modes of transport by land, water and air. However, the relatively low GDP of India has meant that access to these modes of transport has not been uniform. Motor vehicle penetration is low with only 13 million cars on thenation's roads.[1] In addition, only around 10% of Indian households own a motorcycle.[2] At the same time, the Automobile industry in India is rapidly growing with an annual production of over 2.6 million vehicles[3] and vehicle volume is expected to rise greatly in the future.[4] In the interim however, public transport still remains the primary mode of transport for most of the population, and India's public transport systems are among the most heavily utilised in the world.[5] India's rail network is the longest and fourth most heavily used system in the world transporting over 6 billionpassengers and over 350 million tons of freight annually.[5][6] Despite ongoing improvements in the sector, several aspects of the transport sector are still riddled with problems due to outdated infrastructure, lack of investment, corruption and a burgeoning population. The demand for transport infrastructure and services has been rising by around 10% a year[5] with the current infrastructure being unable to meet these growing demands. According to recent estimates by Goldman Sachs, India will need to spend $1.7 Trillion USD on infrastructure projects over the next decade to boost economic growth of which $500 Billion USD is budgeted to be spent during the eleventh Five-year plan. -

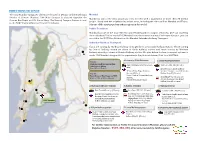

How to Reach TISS: Navigation

DIRECTIONS TO VENUE The two Mumbai Campuses of TISS are located in Deonar in the North-East Mumbai Section of Greater Mumbai. The Main Campus is situated opposite the Mumbai is one of the most populous cities in India with a population of more than 20 million Deonar Bus Depot on V.N. Purav Marg. The Naoroji Campus Annexe is next people. Along with the neighbouring urban areas, including the cities of Navi Mumbai and Thane, to the BARC Hospital Gate on Deonar Farm Road. it is one of the most populous urban regions in the world. Public Transport Mumbai has one of the most efficient and reliable public transport networks. One can travel by Auto-rickshaw/Taxi to reach TISS Mumbai from the nearest stations. For longer distance, you can use either the BEST Bus Network or the Mumbai Suburban Railway Transport. Suburban Railway Transport If you are coming by Harbour Railway Line, get down at Govandi Railway Station. Those coming by Central Railway should get down at Kurla Railway station and those coming by Western Railway should get down at Bandra Railway station. We give below the best transport options to 6 reach TISS Mumbai along with the approximate Bus/Auto-rickshaw/Taxi fare and time. 1. Lokmanya Tilak Terminus 2. DaDar Railway Junction Step S1: From GovanDi Station to TISS Auto-rickshaw Fare: INR 50 (25 Taxi Fare: INR 130 (50 min) Take Auto-rickshaw min) Fare: INR 11 (5 min) Board Train to Kurla Railway Walk to Tilak Nagar Railway Station, Change to Govandi station Step S2: Station (500 m), Follow Step S1 (50 min) From Deonar Bus Depot to TISS Board Train to Govandi Railway Station, Board Bus# 92, 93, 521, 520, Walk to TISS at 200 m (5 min) AC 592 to Deonar Bus Depot 8 Follow Step S1 (30 min) Follow Step S2 (60 min) 3. -

49469-007: Mumbai Metro Rail Systems Project

Mumbai Metro Rail Systems Project (RRP IND 49469) SECTOR ASSESSMENT (SUMMARY): TRANSPORT (RAIL AND URBAN)1 Sector Road Map 1. Sector Performance, Problems, and Opportunities 1. Urban transport. Efficient and sustainable urban transport systems and mobility are critical for the smooth functioning of India’s cities. From 1981 to 2011, the number of total registered vehicles grew at a rate of 11.7% per year, compared to population growth of 2% per year.2 The rapid increase in the number of vehicles has led to severe air pollution, which is becoming a serious health hazard in many cities. The government is consequently committed to promoting public transport systems. Public transportation infrastructure in India needs high levels of investment and massive upgrading to spur a modal shift from private vehicles. It is estimated that over 50% of Indians will be living in urban areas by 2050.3 In 2006, the Government of India issued the National Urban Transport Policy (NUTP) that provides a broad framework for development of urban transport.4 Metro rail is seen as a necessary solution for developing mass rapid transit systems in India’s large cities, while smaller and medium-sized cities are exploring the option of bus rapid transit. 2. In India, the states and union territories plan, execute, and develop urban transport facilities. However, the current suburban railway system is within the purview of the national railway administration. Indian Railways has been operating suburban rail services in Chennai, Delhi, Hyderabad, Kolkata, and Mumbai, as a means of rail-based mass transit with a focus on long-haul freight and passenger movement. -

Visceral Politics of Food: the Bio-Moral Economy of Work- Lunch in Mumbai, India

Visceral politics of food: the bio-moral economy of work- lunch in Mumbai, India Ken Kuroda London School of Economics and Political Science A thesis submitted to the Department of Anthropology of the London School of Economics for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, London, March 2018 1 Declaration I certify that the thesis I have presented for examination for the MPhil/PhD degree of the London School of Economics and Political Science is solely my own work other than where I have clearly indicated that it is the work of others (in which case the extent of any work carried out jointly by me and any other person is clearly identified in it). The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. Quotation from it is permitted, provided that full acknowledgement is made. This thesis may not be reproduced without my prior written consent. I warrant that this authorisation does not, to the best of my belief, infringe the rights of any third party. I declare that my thesis consists of 98896 words. 2 Abstract This Ph.D. examines how commuters in Mumbai, India, negotiate their sense of being and wellbeing through their engagements with food in the city. It focuses on the widespread practice of eating homemade lunches in the workplace, important for commuters to replenish mind and body with foods that embody their specific family backgrounds, in a society where religious, caste, class, and community markers comprise complex dietary regimes. Eating such charged substances in the office canteen was essential in reproducing selfhood and social distinction within Mumbai’s cosmopolitan environment. -

Mumbai 2006: Railway Dwellers Case Report

MSc. Environment and Sustainable Development Field Trip MSc. Urban Development Planning 2006 Addressing the Costs & Opportunities of Relocation in the Transformation of the Living Conditions of the Poor The Case of Railway Slum Dwellers 5,930 words We certify that the work submitted is our own and that any material derived or quoted from the published or unpublished work of other persons has been duly acknowledged. We confirm that we have read the notes on plagiarism in the MSc course guide. Group Members Christian Bruckhart Leena Patel Daniel Viliesid Marc Sielschott Diana Sandoval Nahla Sabet Dimitra Adamantidou Yuko Kanasaka Hannah Griffiths June 2nd, 2006 Addressing the Costs & Opportunities of Relocation in the Transformation of Living Conditions of the Poor The Case of Railway Slum Dwellers TABLE OF CONTENTS _Toc136952770 1 ACRONYMS AND GLOSSARY ........................................................................................ 6 2 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS.................................................................................................. 10 3 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................................ 11 3.1 Background.........................................................................................................11 3.2 Terms of Reference.............................................................................................11 3.3 Diagnosis and Findings.......................................................................................12 3.4 Strategies, -

Travel Based Multitasking on the Mumbai Local and Metro: Measurement, Classification and Variation by Karthikeyan Kuppu Sundara

Travel Based Multitasking on the Mumbai Local and Metro: Measurement, Classification and Variation By Karthikeyan Kuppu Sundara Raman Bachelor in Architecture Indian Institute of Technology, Kharagpur Kharagpur, India (2017) Submitted to the Department of Urban Studies and Planning in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master in City Planning at the MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY February 2019 © 2019 Karthikeyan Kuppu Sundara Raman. All Rights Reserved The author hereby grants to MIT the permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of the thesis document in whole or in part in any medium now known or hereafter created. Author________________________________________________________________________ Department of Urban Studies and Planning December 19, 2018 Certified by ___________________________________________________________________ Associate Professor Jinhua Zhao Department of Urban Studies and Planning Thesis Supervisor Accepted by___________________________________________________________________ Associate Professor P. Christopher Zegras Chair, MCP Committee Department of Urban Studies and Planning Travel Based Multitasking on the Mumbai Local and Metro: Measurement, Classification and Variation By Karthikeyan Kuppu Sundara Raman Submitted to the Department of Urban Studies and Planning on January 14, 2019 in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master in City Planning Abstract Review of travel based multitasking (TBM) behavior has shown that activities performed during travel is of growing interest in the field of transportation planning and mobility behavior. There is a lack of literature looking at this subject in cities in developing countries. This thesis examines TBM activities occurring on mass transit modes in the Mumbai Metropolitan Region. It takes the Western Line of the Mumbai Suburban Railway and the upcoming Line II and III of the Mumbai Metro as case studies to understand TBM activities in the Indian context. -

World Bank Document

The World Bank Mumbai Urban Transport Project 3 (P159782) Note to Task Teams: The following sections are system generated and can only be edited online in the Portal. Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Project Information Document/ Integrated Safeguards Data Sheet (PID/ISDS) Concept Stage | Date Prepared/Updated: 29-Aug-2017 | Report No: PIDISDSC20633 Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Jun 28, 2017 Page 1 of 12 The World Bank Mumbai Urban Transport Project 3 (P159782) BASIC INFORMATION A. Basic Project Data OPS TABLE Country Project ID Parent Project ID (if any) Project Name India P159782 Mumbai Urban Transport Project 3 (P159782) Region Estimated Appraisal Date Estimated Board Date Practice Area (Lead) SOUTH ASIA Aug 20, 2018 Dec 18, 2018 Transport & ICT Financing Instrument Borrower(s) Implementing Agency Investment Project Financing Mumbai Railway Vikas Mumbai Railway Vikas Corporation (MRVC) Corporation (MRVC) Proposed Development Objective(s) The Project’s Development Objective is to improve the network connectivity, service quality and safety of Mumbai’s suburban railway system with particular attention to female passengers, and better integrate the system with the Mumbai Metropolitan Region Plan both at the network level and through transit oriented development initiatives at specific stations. Financing (in USD Million) Finance OLD Financing Source Amount Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank 500.00 Borrower 1,500.00 International Bank for Reconstruction and Development 500.00 Total Project Cost 2,500.00 Environmental Assessment Category Concept Review Decision A-Full Assessment Track II-The review did authorize the preparation to continue Note to Task Teams: End of system generated content, document is editable from here. -

Dahisar (E)Corridor of Mumbai Metro

ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT FOR ANDHERI (E)- DAHISAR (E)CORRIDOR OF MUMBAI METRO A PROJECT BY MUMBAI METROPOLITON REGION DEVELOPMENT AUTHORITY (MMRDA) PREPARED BY FINE ENVIROTECH ENGINEERS APRIL 2018 INDEX EIA report of proposed Andher (E) –Dahisar (E) Corridor of Mumbai Metro Project by MMRDA CONTENT No. Description Page No. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 0.1 INTRODUCTION 1 0.1.1 Objective and Scope of the Study 1 0.1.2 Approach and Methodology 1 0.1.3 Need of the Project 1 0.1.4 General Advantages of Metro Railway System: 1 0.2 PROJECT DESCRIPTION 2 0.2.1 Transport Demand and Forecast 2 0.2.2 Proposed Metro Corridor 2 0.2.2.1 Route Alignment 2 0.2.2.2 Route Length and Stations 2 0.2.2.3 Rolling Stock Requirement 3 0.2.3 Construction Methodology 3 0.3 Purpose of preparation of EIA Report 3 0.3.1 Applicability of Environmental, Coastal Regulatory Zone notification 3 and Forest Clearance 0.3.2 ENVIRONMENTAL BASELINE DATA 3 0.3.2.1 Environmental Scoping 3 0.3.3 Land Environment 4 0.3.4 Water Environment 4 0.3.4.1 Water Resources 4 0.3.4.2 Ground Water 4 0.3.4.3 Water Quality 4 0.3.5 Meteorology 4 0.3.6 Air Environment 4 0.3.7 Noise Environment 4 0.3.8 Existing Trees 5 0.3.9 Socio- Economic Conditions 5 0.3.10 Socio-Economic Survey 5 0.3.11 Archaeological Sites 5 0.4 NEGATIVE ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACTS 5 0.4.1 General 5 0.4.2 Environmental Impacts 5 0.4.3 Impacts Due To Project Location 5 0.4.4 Impacts Due To Project Design 6 0.4.5 Impacts Due To Project Construction 6 0.4.6 Impacts Due To Project Operation 6 0.4.7 Impacts Due to Depot 7 0.5 POSITIVE -

Engendering Mumbai's Suburban Railway System

Engendering Mumbai's Suburban Railway System Amita Bhide Ratoola Kundu Payal Tiwari A Study Conducted by Centre for Urban Policy and Governance, Tata Institute of Social Sciences Engendering Mumbai’s Suburban Railway System Amita Bhide Ratoola Kundu Payal Tiwari A Study Conducted by Centre for Urban Policy and Governance Tata Institute of Social Sciences 2016 Contents List of Tables ...................................................................................... 1 Acknowledgement ............................................................................... 2 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ....................................................................... 4 1 Introduction and Methodology .................................................... 9 1.1 The Suburban Railway System and the transitioning economic geography of Mumbai ................................................................................................................................. 9 1.2 Increased workforce participation rate amongst women in the city ...................... 11 1.3 Methodology ........................................................................................................... 13 2 Experiences of Commuting ........................................................ 19 2.1 Profile and travel behaviour of respondents .......................................................... 19 2.2 Affordability ............................................................................................................. 24 2.3 Accessibility ............................................................................................................ -

1.Introduction

PRE – FEASIBILITY STUDY OF PROPOSED QUARDUPLING OF VIRAR – DAHANU ROAD SECTION 11.. INTRODUCTION 1.1 BACKGROUND Mumbai, with a population of over 13 million is the largest metropolis in India and one of the most populous cities in the world. It is expected to have a population of 34.0 million by 2031. To cater to the mobility needs, an efficient suburban rail system runs across of MMR. The existing suburban rail system is one of the most crowded and overloaded suburban systems in the world. Two zonal railways, the Western Railway (WR) and the Central Railway (CR), operate the Mumbai Suburban Railway system. Western Railway operates the Western Line from Churchgate to Dahanu Road (124 km) and the Central Railway operates the Central and Harbour Lines. The Corridor from Churchgate to Mumbai Central and from Borivili to Virar consists of quadruple lines, while Mumbai Central to Borivili has 5 lines except Mahim to Santacruz, where 5th line is under construction. Further, two harbour lines of Central Railway run parallel to Western Railway network from Santacruz to Andheri. The City is expanding towards Virar and beyond. Many large and medium scaled industries have come up between Virar and Dahanu Road due to comparatively cheaper land. To meet the mobility requirements, Indian Railways (IR) and Government of Maharashtra (GoM) through Mumbai Rail Vikas Corporation (MRVC) Ltd., Metropolitan Regional Development Authority (MMRDA) and the World Bank (WB) have planned a comprehensive investment scheme for improving and expanding the transportation network of Mumbai, through Mumbai Urban Transport Project (MUTP). MUTP I & II has given the kick to provide 5th & 6th Lines between Kurla – Thane, Quadrupling of section between Borivali – Virar, 5th Line between Mahim – Santacruz, conversion of services from DC to AC, 5th & 6th lines between CSTM – Kurla and Thane – Diwa, 6th line between Borivali – Mumbai Central, Extension of Harbour line from Andheri to Goregaon and DC to AC conversion from CST Mumbai to Thane.