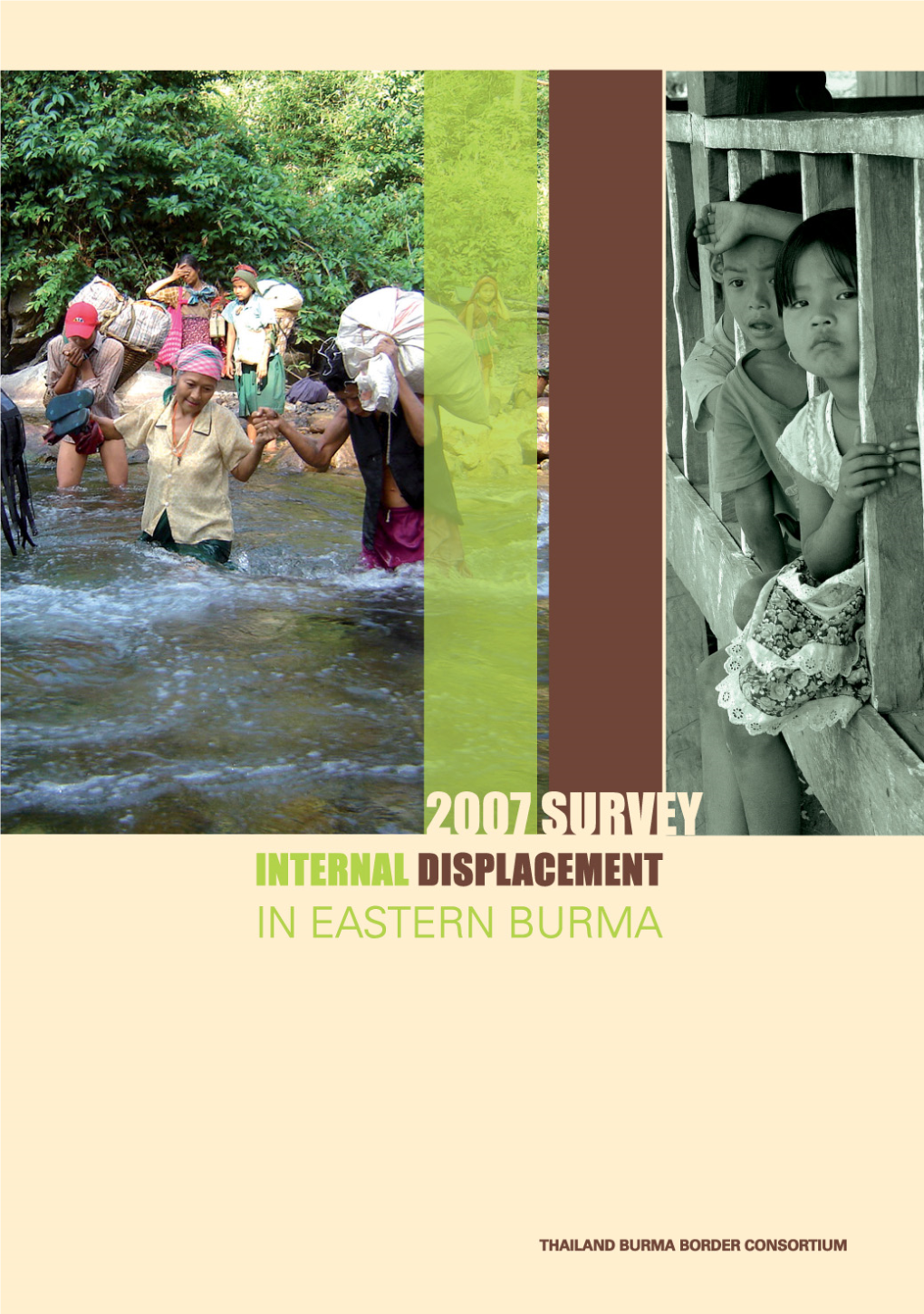

Internal Displacement in Eastern Burma

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Important Facts About the 2015 General Election Enlightened Myanmar Research Foundation - Emref

Important Facts about the 2015 Myanmar General Election Enlightened Myanmar Research Foundation (EMReF) 2015 October Important Facts about the 2015 General Election Enlightened Myanmar Research Foundation - EMReF 1 Important Facts about the 2015 General Election Enlightened Myanmar Research Foundation - EMReF ENLIGHTENED MYANMAR RESEARCH ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ABSTRACT FOUNDATION (EMReF) This report is a product of the Information Enlightened Myanmar Research Foundation EMReF is an accredited non-profit research Strategies for Societies in Transition program. (EMReF has been carrying out political-oriented organization dedicated to socioeconomic and This program is supported by United States studies since 2012. In 2013, EMReF published the political studies in order to provide information Agency for International Development Fact Book of Political Parties in Myanmar (2010- and evidence-based recommendations for (USAID), Microsoft, the Bill & Melinda Gates 2012). Recently, EMReF studied The Record different stakeholders. EMReF has been Foundation, and the Tableau Foundation.The Keeping and Information Sharing System of extending its role in promoting evidence-based program is housed in the University of Pyithu Hluttaw (the People’s Parliament) and policy making, enhancing political awareness Washington's Henry M. Jackson School of shared the report to all stakeholders and the and participation for citizens and CSOs through International Studies and is run in collaboration public. Currently, EMReF has been regularly providing reliable and trustworthy information with the Technology & Social Change Group collecting some important data and information on political parties and elections, parliamentary (TASCHA) in the University of Washington’s on the elections and political parties. performances, and essential development Information School, and two partner policy issues. -

Weekly Security Review (27 August – 2 September 2020)

Commercial-In-Confidence Weekly Security Review (27 August – 2 September 2020) Weekly Security Review Safety and Security Highlights for Clients Operating in Myanmar 27 August – 2 September 2020 Page 1 of 27 Commercial-In-Confidence Weekly Security Review (27 August – 2 September 2020) EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................................................................................. 3 Internal Conflict ....................................................................................................................................... 4 Nationwide .......................................................................................................................................... 4 Rakhine State ....................................................................................................................................... 4 Shan State ............................................................................................................................................ 5 Myanmar and the World ......................................................................................................................... 8 Election Watch ........................................................................................................................................ 8 Social and Political Stability ................................................................................................................... 11 Transportation ...................................................................................................................................... -

Appendix 6 Satellite Map of Proposed Project Site

APPENDIX 6 SATELLITE MAP OF PROPOSED PROJECT SITE Hakha Township, Rim pi Village Tract, Chin State Zo Zang Village A6-1 Falam Township, Webula Village Tract, Chin State Kim Mon Chaung Village A6-2 Webula Village Pa Mun Chaung Village Tedim Township, Dolluang Village Tract, Chin State Zo Zang Village Dolluang Village A6-3 Taunggyi Township, Kyauk Ni Village Tract, Shan State A6-4 Kalaw Township, Myin Ma Hti Village Tract and Baw Nin Village Tract, Shan State A6-5 Ywangan Township, Sat Chan Village Tract, Shan State A6-6 Pinlaung Township, Paw Yar Village Tract, Shan State A6-7 Symbol Water Supply Facility Well Development by the Procurement of Drilling Rig Nansang Township, Mat Mon Mun Village Tract, Shan State A6-8 Nansang Township, Hai Nar Gyi Village Tract, Shan State A6-9 Hopong Township, Nam Hkok Village Tract, Shan State A6-10 Hopong Township, Pawng Lin Village Tract, Shan State A6-11 Myaungmya Township, Moke Soe Kwin Village Tract, Ayeyarwady Region A6-12 Myaungmya Township, Shan Yae Kyaw Village Tract, Ayeyarwady Region A6-13 Labutta Township, Thin Gan Gyi Village Tract, Ayeyarwady Region Symbol Facility Proposed Road Other Road Protection Dike Rainwater Pond (New) : 5 Facilities Rainwater Pond (Existing) : 20 Facilities A6-14 Labutta Township, Laput Pyay Lae Pyauk Village Tract, Ayeyarwady Region A6-15 Symbol Facility Proposed Road Other Road Irrigation Channel Rainwater Pond (New) : 2 Facilities Rainwater Pond (Existing) Hinthada Township, Tha Si Village Tract, Ayeyarwady Region A6-16 Symbol Facility Proposed Road Other Road -

Initial Rapid Assessment of Selected Idp Settlements in Kayin and Tanintharyi, Myanmar

2013 Unicef Myanmar Nina Victoria Mattus Justiniani [INITIAL RAPID ASSESS MENT OF SELECTED IDP SETTLEMENTS IN KAYIN AND TANINTHARYI, MYANMAR] A report on 131 villages with internally displaced persons in Kayin state and Tanintharyi region, South East Myanmar. This report is based on an initial rapid assessment exercise carried out by volunteers from various faith-based organizations in late February to April, 2013. TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements ...................................................................................................................................... iv Acronyms ...................................................................................................................................................... v EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .................................................................................................................................. 6 I. INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................................................... 10 BACKGROUND ......................................................................................................................................... 10 OBJECTIVES OF THE INITIAL RAPID ASSESSMENT .................................................................................. 10 METHODOLOGY, SCOPE AND LIMITATIONS ........................................................................................... 11 III. IDP CHILDREN AND THEIR VILLAGES ................................................................................................... -

The Union Report the Union Report : Census Report Volume 2 Census Report Volume 2

THE REPUBLIC OF THE UNION OF MYANMAR The 2014 Myanmar Population and Housing Census The Union Report The Union Report : Census Report Volume 2 Volume Report : Census The Union Report Census Report Volume 2 Department of Population Ministry of Immigration and Population May 2015 The 2014 Myanmar Population and Housing Census The Union Report Census Report Volume 2 For more information contact: Department of Population Ministry of Immigration and Population Office No. 48 Nay Pyi Taw Tel: +95 67 431 062 www.dop.gov.mm May, 2015 Figure 1: Map of Myanmar by State, Region and District Census Report Volume 2 (Union) i Foreword The 2014 Myanmar Population and Housing Census (2014 MPHC) was conducted from 29th March to 10th April 2014 on a de facto basis. The successful planning and implementation of the census activities, followed by the timely release of the provisional results in August 2014 and now the main results in May 2015, is a clear testimony of the Government’s resolve to publish all information collected from respondents in accordance with the Population and Housing Census Law No. 19 of 2013. It is my hope that the main census results will be interpreted correctly and will effectively inform the planning and decision-making processes in our quest for national development. The census structures put in place, including the Central Census Commission, Census Committees and Offices at all administrative levels and the International Technical Advisory Board (ITAB), a group of 15 experts from different countries and institutions involved in censuses and statistics internationally, provided the requisite administrative and technical inputs for the implementation of the census. -

December 2008

cover_asia_report_2008_2:cover_asia_report_2007_2.qxd 28/11/2008 17:18 Page 1 Central Committee for Drug Lao National Commission for Drug Office of the Narcotics Abuse Control Control and Supervision Control Board Vienna International Centre, P.O. Box 500, A-1400 Vienna, Austria Tel: (+43 1) 26060-0, Fax: (+43 1) 26060-5866, www.unodc.org Opium Poppy Cultivation in South East Asia Lao PDR, Myanmar, Thailand OPIUM POPPY CULTIVATION IN SOUTH EAST ASIA IN SOUTH EAST CULTIVATION OPIUM POPPY December 2008 Printed in Slovakia UNODC's Illicit Crop Monitoring Programme (ICMP) promotes the development and maintenance of a global network of illicit crop monitoring systems in the context of the illicit crop elimination objective set by the United Nations General Assembly Special Session on Drugs. ICMP provides overall coordination as well as direct technical support and supervision to UNODC supported illicit crop surveys at the country level. The implementation of UNODC's Illicit Crop Monitoring Programme in South East Asia was made possible thanks to financial contributions from the Government of Japan and from the United States. UNODC Illicit Crop Monitoring Programme – Survey Reports and other ICMP publications can be downloaded from: http://www.unodc.org/unodc/en/crop-monitoring/index.html The boundaries, names and designations used in all maps in this document do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations. This document has not been formally edited. CONTENTS PART 1 REGIONAL OVERVIEW ..............................................................................................3 -

Dooplaya Situation Update: Kawkareik Township, January to October 2016

Situation Update July 18, 2017 / KHRG # 16-92-S1 Dooplaya Situation Update: Kawkareik Township, January to October 2016 This Situation Update describes events occurring in Kawkareik Township, Dooplaya District during the period between January and October 2016, and includes issues regarding army base locations, rape, drugs, villagers’ livelihood, military activities, refugee concerns, development, education, healthcare, land and taxation. • In the last two months, a Burmese man from A--- village raped and killed a 17-year-old girl. The man was arrested and was sent to Tatmadaw military police. The man who committed the rape was also under the influence of drugs. • Drug abuse has been recognised as an ongoing issue in Dooplaya District. Leaders and officials have tried to eliminate drugs, but the drug issue remains. • Refugees from Noh Poe refugee camp in Thailand are concerned that they will face difficulties if they return to Burma/Myanmar because Bo San Aung’s group (DKBA splinter group) started fighting with BGF and Tatmadaw when the refugees were preparing for their return to Burma/Myanmar. The ongoing fighting will cause problems for refugees if they return. Local people residing in Burma/Myanmar are also worried for refugees if they return because fighting could break out at any time. • There are many different armed groups in Dooplaya District who collect taxes. A local farmer reported that he had to pay a rice tax to many different armed groups, which left him with little money after. Situation Update | Kawkareik Township, Dooplaya District (January to October 2016) The following Situation Update was received by KHRG in November 2016. -

English 2014

The Border Consortium November 2014 PROTECTION AND SECURITY CONCERNS IN SOUTH EAST BURMA / MYANMAR With Field Assessments by: Committee for Internally Displaced Karen People (CIDKP) Human Rights Foundation of Monland (HURFOM) Karen Environment and Social Action Network (KESAN) Karen Human Rights Group (KHRG) Karen Offi ce of Relief and Development (KORD) Karen Women Organisation (KWO) Karenni Evergreen (KEG) Karenni Social Welfare and Development Centre (KSWDC) Karenni National Women’s Organization (KNWO) Mon Relief and Development Committee (MRDC) Shan State Development Foundation (SSDF) The Border Consortium (TBC) 12/5 Convent Road, Bangrak, Suite 307, 99-B Myay Nu Street, Sanchaung, Bangkok, Thailand. Yangon, Myanmar. E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] www.theborderconsortium.org Front cover photos: Farmers charged with tresspassing on their own lands at court, Hpruso, September 2014, KSWDC Training to survey customary lands, Dawei, July 2013, KESAN Tatmadaw soldier and bulldozer for road construction, Dawei, October 2013, CIDKP Printed by Wanida Press CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................................................................... 1 1. INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................. 3 1.1 Context .................................................................................................................................. 4 1.2 Methodology ........................................................................................................................ -

Union NPED Minister Attends ASEAN Economic Ministers Meeting

THENew MOST RELIABLE NEWSPAPER LightAROUND YOU of Myanmar Volume XXI, Number 131 4th Waning of Wagaung 1375 ME Sunday, 25 August, 2013 INSIDE Union NPED Minister attends ASEAN INSIDE I AM PROUD Abe leaves for trip OF BEING A Economic Ministers meeting to 3 GCC coun- PHONGYI tries, Djibouti KYAUNGTHAR Maung Hlaing PAGE-8 Mann Creek water reaches Footprint of PAGE-3 Buddha at Mann Settawya Pagoda PERFORMING ARTS PAGE-4 PAGE-2 Brazil’s Rousseff’s Tourists enjoy popularity riding elephants rises in poll as in Thabeikkyin Union Minister for National Planning and Economic Development Dr Kan Zaw poses for documentary economy stumbles region photo together with his counterparts of ASEAN countries.—MNA N AY P YI T AW, 24 talks on cooperation the opening of ASEAN with ASEAN dialogue Aug—Union Minister for between the government Economy and Investment partners. He held talks National Planning and and entrepreneurs at Summit held at Brunei with Mr Toshimitsu Economic Development the working lunch of International Convention Motegi, Japanese Minister Dr Kan Zaw attended the the ASEAN Economy Center. for Economy, Trade and working dinner of ASEAN Advisory Council. Afterwards, he Industry on 20 August, a PAGE-6 PAGE-7 Economic Ministers at He attended 45th attended the coordination delegation led by Chairman Flood victims Empire Hotel & Country meetings of ASEAN meetings, a dinner hosted of ASEAN-US Economic and University of Brunei accommodated Club on 18 August in Economic Ministers and by His Royal Highness Council Mr Alexander Darussalam. Brunei. 10th ASEAN Economic Prince Mohamed Bilkiah Feldman and US trade After that, the Union in safe places in On 19 August, the Community Council, and the Minister for Foreign representative Mr Michael minister held talks with Kalay Tsp Union minister also Ministerial level meeting of Affairs and Trade and the Froman on 21 August. -

PA) PROFILES LENYA LANDSCAPE (“R2R Lenya”, Aka Lenya Proposed Protected Area, Which Is Currently Lenya Reserved Forest

ANNEX 11: Lenya Profile LANDSCAPE / SEASCAPE AND PROTECTED AREA (PA) PROFILES LENYA LANDSCAPE (“R2R Lenya”, aka Lenya Proposed Protected Area, which is currently Lenya Reserved Forest) Legend for this map of Lenya Landscape is provided at the end of this annex. I. Baseline landscape context 1. 1 Defining the landscape: Lenya Landscape occupies the upper Lenya River Basin in Kawthaung District, and comprises the Lenya Proposed National Park (LPNP), which was announced in 2002 for the protection of Gurney’s pitta and other globally and nationally important species, all of which still remain (see below). The LPNP borders align with those of the Lenya Reserve Forest (RF) under which the land is currently classified, however its status as an RF has to date not afforded it the protection from encroachment and other destructive activities to protect the HCVs it includes. The Lenya Proposed National Park encompasses an area of 183,279ha directly south of the Myeik-Kawthaung district border, with the Lenya Proposed National Park Extension boundary to the north, the Parchan Reserve Forest to the south and the Thai border to the east. The site is located approximately 260km south of the regional capital of Dawei and between 20-30km east of the nearest administrative town of Bokpyin. Communities are known to reside within the LPNP area as well as on its immediate boundaries across the LPNP. Some small settled areas can be found in the far south-east, along the Thai border, where heavy encroachment by smallholder agriculture can also be found and where returning Myanmar migrants to Thailand may soon settle; Karen villages which have resettled (following the signing of a peace treaty between the Karen National Union (KNU) and the Myanmar government) on land along the Lenya River extending into the west of LPNP; and in the far north where a significant number of hamlets (in addition to the Yadanapon village) have developed in recent years along the the Yadanapon road from Lenya village to Thailand. -

System of Impunity

SYSTEM OF IMPUNITY Nationwide Patterns of Sexual Violence by the Military Regime’s Army and Authorities in Burma The Women’s League of Burma (WLB) September 2004 Women’s League of Burma The Women’s League of Burma (WLB) is an umbrella organisation comprising 11 women’s organisations of different ethnic backgrounds from Burma. WLB was founded on 9th December, 1999. Its mission is to work for women’s empowerment and advancement of the status of women, and to work for the increased participation of women in all spheres of society in the democracy movement, and in peace and national reconciliation processes through capacity building, advocacy, research and documentation. Aims • To work for the empowerment and development of women. • To encourage women’s participation in decision-making in all spheres of life. • To enable women to participate effectively in the movement for peace, democracy and national reconciliation. By working together, and encouraging cooperation between the different groups, the Women’s League of Burma hopes to build trust, solidarity and mutual understanding among women of all nationalities in Burma. The 11 member organisations are listed on the inside back cover of this report. Contact address: Women's League of Burma ( WLB) P O Box 413, G P O Chiangmai 50000 Thailand [email protected] www.womenorfburma.org Table of Contents Page Number Acknowledgements Acronyms Map 1 Map of Burma: States & Divisions Map 2 Locations of Sexual Violence Documented in this Report Executive Summary .................................................................................. 1 Methodology .............................................................................................. 3 Background Over four decades of military rule ............................................... 3 Continuing civil war ....................................................................... 4 Increased militarization .................................................................... 5 Systematic sexual violence in Burma .............................................. -

Fact Book of Political Parties in Myanmar

Myanmar Development Research (MDR) (Present) Enlightened Myanmar Research (EMR) Wing (3), Room (A-305) Thitsar Garden Housing. 3 Street , 8 Quarter. South Okkalarpa Township. Yangon, Myanmar +951 562439 Acknowledgement of Myanmar Development Research This edition of the “Fact Book of Political Parties in Myanmar (2010-2012)” is the first published collection of facts and information of political parties which legally registered at the Union Election Commission since the pre-election period of Myanmar’s milestone 2010 election and the post-election period of the 2012 by-elections. This publication is also an important milestone for Myanmar Development Research (MDR) as it is the organization’s first project that was conducted directly in response to the needs of civil society and different stakeholders who have been putting efforts in the process of the political transition of Myanmar towards a peaceful and developed democratic society. We would like to thank our supporters who made this project possible and those who worked hard from the beginning to the end of publication and launching ceremony. In particular: (1) Heinrich B�ll Stiftung (Southeast Asia) for their support of the project and for providing funding to publish “Fact Book of Political Parties in Myanmar (2010-2012)”. (2) Party leaders, the elected MPs, record keepers of the 56 parties in this book who lent their valuable time to contribute to the project, given the limited time frame and other challenges such as technical and communication problems. (3) The Chairperson of the Union Election Commission and all the members of the Commission for their advice and contributions.