Navigating Implicit Bias Within Corporate Volunteer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Touchstones of Popular Culture Among Contemporary College Students in the United States

Minnesota State University Moorhead RED: a Repository of Digital Collections Dissertations, Theses, and Projects Graduate Studies Spring 5-17-2019 Touchstones of Popular Culture Among Contemporary College Students in the United States Margaret Thoemke [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://red.mnstate.edu/thesis Part of the Higher Education and Teaching Commons Recommended Citation Thoemke, Margaret, "Touchstones of Popular Culture Among Contemporary College Students in the United States" (2019). Dissertations, Theses, and Projects. 167. https://red.mnstate.edu/thesis/167 This Thesis (699 registration) is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at RED: a Repository of Digital Collections. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Projects by an authorized administrator of RED: a Repository of Digital Collections. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Touchstones of Popular Culture Among Contemporary College Students in the United States A Thesis Presented to The Graduate Faculty of Minnesota State University Moorhead By Margaret Elizabeth Thoemke In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Teaching English as a Second Language May 2019 Moorhead, Minnesota iii Copyright 2019 Margaret Elizabeth Thoemke iv Dedication I would like to dedicate this thesis to my three most favorite people in the world. To my mother, Heather Flaherty, for always supporting me and guiding me to where I am today. To my husband, Jake Thoemke, for pushing me to be the best I can be and reminding me that I’m okay. Lastly, to my son, Liam, who is my biggest fan and my reason to be the best person I can be. -

Pastor Brian Writes— Before Actually Sitting Down Additional Services

January, 2016 UPCOMING EVENTS Pastor Brian Writes— January 10—Mission Sunday Before actually sitting down additional services. Hospital and and taking time to reflect on the home visits. Let’s not forget all the January 10—Food for the Poor year’s past I have to admit if felt baptisms in 2015! somewhat frustrated. “NOT There were family events, January 10—Dave Ramsey FPU MUCH!”, I said. Not much council meetings, elder meetings, Seminar happened in 2015. It seemed to worship team practice, and just come and go. “Same old’ Confirmation which gives evidence January 17—Bowling Family same old’.” That is until someone to the fact that Mission and Event who heard me say that reminded ministry was also an important part me just how far I was from reality. of a very busy 2015. Canteen Visit the calendar at www.friendshiplutheran.com In reality it was a busy year Run, Panera Bread mission, like so many before it and I was Elizabeth Circle, Men’s Tuesday once again reminded to give Morning Bible Study, Thursday INSIDE THIS ISSUE: thanks to the ONE who made it all Morning Bible Study and small possible and who saw all of us groups that were in full swing. Budgets 2 through it. So, I did what I suppose THE STORY concluded in May. With the Young Crowd 2-5 many of us have done before. I Prayer and praise took place on Family Events 5 flipped back my desk calendar to Thursdays. Central Illinois District Lent Schedule & Themes 6 January and paged slowly through conferences took place twice in it. -

Confessions of a Black Female Rapper: an Autoethnographic Study on Navigating Selfhood and the Music Industry

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University African-American Studies Theses Department of African-American Studies 5-8-2020 Confessions Of A Black Female Rapper: An Autoethnographic Study On Navigating Selfhood And The Music Industry Chinwe Salisa Maponya-Cook Georgia State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/aas_theses Recommended Citation Maponya-Cook, Chinwe Salisa, "Confessions Of A Black Female Rapper: An Autoethnographic Study On Navigating Selfhood And The Music Industry." Thesis, Georgia State University, 2020. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/aas_theses/66 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of African-American Studies at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in African-American Studies Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CONFESSIONS OF A BLACK FEMALE RAPPER: AN AUTOETHNOGRAPHIC STUDY ON NAVIGATING SELFHOOD AND THE MUSIC INDUSTRY by CHINWE MAPONYA-COOK Under the DireCtion of Jonathan Gayles, PhD ABSTRACT The following research explores the ways in whiCh a BlaCk female rapper navigates her selfhood and traditional expeCtations of the musiC industry. By examining four overarching themes in the literature review - Hip-Hop, raCe, gender and agency - the author used observations of prominent BlaCk female rappers spanning over five deCades, as well as personal experiences, to detail an autoethnographiC aCCount of self-development alongside pursuing a musiC career. MethodologiCally, the author wrote journal entries to detail her experiences, as well as wrote and performed an aCCompanying original mixtape entitled The Thesis (available on all streaming platforms), as a creative addition to the research. -

I Sing Because I'm Free‖: Developing a Systematic Vocal Pedagogy For

―I Sing Because I‘m Free‖: Developing a Systematic Vocal Pedagogy for the Modern Gospel Singer D. M. A. Document Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Musical Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Crystal Yvonne Sellers Graduate Program in Music The Ohio State University 2009 Dissertation Committee: Loretta Robinson, Advisor Karen Peeler C. Patrick Woliver Copyright by Crystal Yvonne Sellers 2009 Abstract ―I Sing Because I‘m Free‖: Developing a Systematic Vocal Pedagogy for the Modern Gospel Singer With roots in the early songs and Spirituals of the African American slave, and influenced by American Jazz and Blues, Gospel music holds a significant place in the music history of the United States. Whether as a choral or solo composition, Gospel music is accompanied song, and its rhythms, textures, and vocal styles have become infused into most of today‘s popular music, as well as in much of the music of the evangelical Christian church. For well over a century voice teachers and voice scientists have studied thoroughly the Classical singing voice. The past fifty years have seen an explosion of research aimed at understanding Classical singing vocal function, ways of building efficient and flexible Classical singing voices, and maintaining vocal health care; more recently these studies have been extended to Pop and Musical Theater voices. Surprisingly, to date almost no studies have been done on the voice of the Gospel singer. Despite its growth in popularity, a thorough exploration of the vocal requirements of singing Gospel, developed through years of unique tradition and by hundreds of noted Gospel artists, is virtually non-existent. -

Don't Make Me Think, Revisited

Don’t Make Me Think, Revisited A Common Sense Approach to Web Usability Steve Krug Don’t Make Me Think, Revisited A Common Sense Approach to Web Usability Copyright © 2014 Steve Krug New Riders www.newriders.com To report errors, please send a note to [email protected] New Riders is an imprint of Peachpit, a division of Pearson Education. Editor: Elisabeth Bayle Project Editor: Nancy Davis Production Editor: Lisa Brazieal Copy Editor: Barbara Flanagan Interior Design and Composition: Romney Lange Illustrations by Mark Matcho and Mimi Heft Farnham fonts provided by The Font Bureau, Inc. (www.fontbureau.com) Notice of Rights All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. For information on getting permission for reprints and excerpts, contact [email protected]. Notice of Liability The information in this book is distributed on an “As Is” basis, without warranty. While every precaution has been taken in the preparation of the book, neither the author nor Peachpit shall have any liability to any person or entity with respect to any loss or damage caused or alleged to be caused directly or indirectly by the instructions contained in this book or by the computer software and hardware products described in it. Trademarks It’s not rocket surgery™ is a trademark of Steve Krug. Many of the designations used by manufacturers and sellers to distinguish their products are claimed as trademarks. Where those designations appear in this book, and Peachpit was aware of a trademark claim, the designations appear as requested by the owner of the trademark. -

An Intergenerational Narrative Analysis of Black Mothers and Daughters

Still Waiting to Exhale: An Intergenerational Narrative Analysis of Black Mothers and Daughters DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Jamila D. Smith, B.A., MFA College of Education and Human Ecology The Ohio State University 2012 Dissertation Committee: Professor Elaine Richardson, Advisor Professor Adrienne D. Dixson Professor Carmen Kynard Professor Wendy Smooth Professor Cynthia Tyson Copyright by Jamila D. Smith 2012 Abstract This dissertation consists of a nine month, three-state ethnographic study on the intersectional effects of race, age, gender, and place in the lives of fourteen Black mothers and daughters, ages 15-65, who attempt to analyze and critique the multiple and competing notions of Black womanhood as “at risk” and “in crisis.” Epistemologically, the research is grounded in Black women’s narrative and literacy practices, and fills a gap in the existing literature on Black girlhood and Black women’s lived experiences through attention to the development of mother/daughter relationships, generational narratives, societal discourse, and othermothering. I argue that an in-depth analysis and critique of the dominant “at risk” and “in crisis” discourse is necessary to understand the conversations that are and are not taking place between Black mothers and daughters about race, gender, age, and place; that it is important to understand the ways in which Black girls respond to media portrayals and stereotypes; and that it is imperative that we closely examine the existing narratives at play in the everyday lives of intergenerational Black girls and women in Black communities. -

STATIONS of the CROSS Introduction, Contents, Ideas for Use and Scripts © 2011, Cornerstone Media, Inc

STATIONS OF THE CROSS Introduction, Contents, Ideas for Use and Scripts © 2011, Cornerstone Media, Inc. Introduction: This Stations of the Cross Kit is primarily designed to facilitate prayer. Since prayer is any conversation with God, these prayer moments can happen privately or in groups. This kit can be used for large congregations, or for small groups such as youth meetings and retreats, or simply loaned to individuals for private reflection. What is unique about this kit is the use of music. Because this devotional service is designed for teens and adults together, the selection of the songs is done carefully, with both age groups in mind. Each year in February, new songs are selected, and a new kit is produced. For the greatest effect, we recommend you use the newest version. In addition to the Stations of the Cross on CD One, you will find four additional Holy Week Meditations on CD Two. It is our hope that this ancient devotional will fit well with modern songs, and that you, the current generation of adults and teens, will experience “A Journey You’ll Never Forget.” Cornerstone Media would like to thank the Youth Office for the Archdiocese of Louisville, Kentucky for making possible the first version of “Stations of the Cross.” Thanks also goes to Jerry Finn for writing the first script. God bless you. Contents CD One: STATIONS OF THE CROSS CD Two: THE THEMES OF HOLY WEEK • Opening Narration • Station One: Jesus is condemned to death • Holy Thursday: • Station Two: Jesus accepts his cross Why Should We Stay? • Station Three: -

A Sense of Knowing

Catholic Women's Network 877 Spinosa Drive Non-Profit Org. U.S. Postage Sunnyvale C A 94087 PAID 408.245.8663 FAX408.738.2767 Permit No. 553 etworfc Sunnyvale CA for Women's Spirituality Issue No. 88 %sA non-profit educational publication since 1988 September/October/November 2004 Jeri Becker and intuition Wisdom Women to speak at CWN 15th anniversary A Celebration of Wisdom and Freedom will be the theme ofa day-long program, Saturday, August 28 in Cupertino, CA as CWN celebrates 15 years of educational minis try- Columnist Jeri Becker, newly-freed from prison after 23 years will be a featured speaker. Jeri, now living in Santa Rosa, CA has been an artist and columnist for CWN since 1995, a leader of 12- step groups and peer coun selor in prison. Penny Mann, an InterPlay Jeri Becker leader and ordained minister who uses storytelling, move ment, and song, will facilitate the celebrations of the day. Penny has been a featured ritual leader of several CWN June gatherings in the past. The morning pro gram will offer dra matizations of the Voices of five women from history. Speak a sense of ing wisdom of the past for the present will be: *Author Patricia Lynn Reilly as Eve, knowing the Big Momma * Spiritual Director Intuition—our mysterious "sense of knowing" gives us guidance and answers Suzanne Young as Mary, Woman of~ perplexing questions in our lives, if we know how to ask the questions. It might take the Many Faces form of a voice we hear as St. Joan of Arc did . -

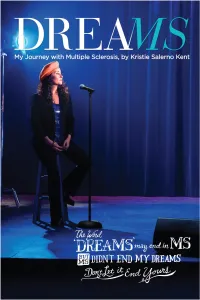

Dreams-041015 1.Pdf

DREAMS My Journey with Multiple Sclerosis By Kristie Salerno Kent DREAMS: MY JOURNEY WITH MULTIPLE SCLEROSIS. Copyright © 2013 by Acorda Therapeutics®, Inc. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. Author’s Note I always dreamed of a career in the entertainment industry until a multiple sclerosis (MS) diagnosis changed my life. Rather than give up on my dream, following my diagnosis I decided to fight back and follow my passion. Songwriting and performance helped me find the strength to face my challenges and help others understand the impact of MS. “Dreams: My Journey with Multiple Sclerosis,” is an intimate and honest story of how, as people living with MS, we can continue to pursue our passion and use it to overcome denial and find the courage to take action to fight MS. It is also a story of how a serious health challenge does not mean you should let go of your plans for the future. The word 'dreams' may end in ‘MS,’ but MS doesn’t have to end your dreams. It has taken an extraordinary team effort to share my story with you. This book is dedicated to my greatest blessings - my children, Kingston and Giabella. You have filled mommy's heart with so much love, pride and joy and have made my ultimate dream come true! To my husband Michael - thank you for being my umbrella during the rainy days until the sun came out again and we could bask in its glow together. Each end of our rainbow has two pots of gold… our precious son and our beautiful daughter! To my heavenly Father, thank you for the gifts you have blessed me with. -

Ot Workshop the GREATEST of THESE IS LOVE Based on 1 Corinthians 13

T e Greatest T ese . IS ot workshop THE GREATEST OF THESE IS LOVE Based on 1 Corinthians 13 This retreat package is prepared with already available materials from the L WML Catalog. It is designed to accomplish two goals: • To provide a complete retreat package complete with Bible study, sketches to introduce sections of the study, suggestions for using various avenues for the study, hymns, get-acquainted activities, devotions, suggested schedules for retreats of various time lengths, and extra activities for weekend retreats. • To illustrate how to put together existing materials from the L WML Catalog on a given topic and create a personalized retreat or program. Permission to copy any materials from this project is given and encouraged for group use. The Christian Resources Editors Committee 1999-2001 The Gt-eatest of These is LOVE MATERIALS INCLUDED (in the order in which they appear in the packet) How to Plan a Retreat Overnight Retreat Schedule Weekend Retreat Schedule Helps and Suggestions Hymn and Song Suggestions A Welcome Litany Chris Fiechtl #5376 Meditation on Corinthians Diane Rahe #5363 Let Me Introduce You ... Lisa Moore #5604 Heart Patterns with LOVE Verses Heart Quilt Template At the End ofthe Day Vivian Nelson #5305 Energized by Freedom Ruth Koch # 23 More Bright Ideas The Greatest of These is Love Rev. Victor Roth #5205 Love in Action Dorothy Kohr #5316 Who is My Neighbor? Unknown #5260 Who Will Wear the Crown? Ruth Dexheimer #5432 Collection ofLitanies Friendship Hearts Template One in Christ Cheryl Schultz #5455 Collection ofLitanies Evaluation Form Sample Love Notes from Scripture Sample Registration and Publicity Materials •!• HOW TO PLAN A RETREAT When your group determines they would like to have a retreat, they will need to decide: 1. -

Misleading and Misrepresenting the American Youth: “Little Orphan Annie” and the Orphan Myth in the Twentieth Century ___

MISLEADING AND MISREPRESENTING THE AMERICAN YOUTH: “LITTLE ORPHAN ANNIE” AND THE ORPHAN MYTH IN THE TWENTIETH CENTURY ________________ A Senior Honors Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of The Honors College University of Houston ________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Arts _______________ By Amanda G. Beck May 2020 MISLEADING AND MISREPRESENTING THE AMERICAN YOUTH: “LITTLE ORPHAN ANNIE” AND THE ORPHAN MYTH IN THE TWENTIETH CENTURY _______________________________________ Amanda G. Beck APPROVED: _______________________________________ Marina Trninic, Visiting Assistant Professor Honors College Thesis Director ______________________________________ Douglas Erwing, Lecturer Honors College Second Reader _____________________________________ Robert Cremins, Lecturer Honors College Honors Reader _______________________________ William Monroe Dean of the Honors College ! MISLEADING AND MISREPRESENTING THE AMERICAN YOUTH: “LITTLE ORPHAN ANNIE” AND THE ORPHAN MYTH IN THE TWENTIETH CENTURY ________________ An Abstract of a Senior Honors Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of The Honors College University of Houston ________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Arts _______________ By Amanda G. Beck May 2020 ! Abstract ____________________________ This interdisciplinary thesis examines the myth of the orphan in twentieth-century America as exemplified through the recurring story of “Little Orphan Annie,” an iconic American figure of independence, resilience, and optimism. By providing historical context and literary analysis for each of Annie’s crucial moments in the twentieth century, this thesis shows how the character has advanced a misguided perception of orphan and youth agency. While evolving to represent different decades of American society in the twentieth century through different mediums, Annie has further misled Americans in their perception of orphan and youth agency. -

Raw Thought: the Weblog of Aaron Swartz Aaronsw.Com/Weblog

Raw Thought: The Weblog of Aaron Swartz aaronsw.com/weblog 1 What’s Going On Here? May 15, 2005 Original link I’m adding this post not through blogging software, like I normally do, but by hand, right into the webpage. It feels odd. I’m doing this because a week or so ago my web server started making funny error messages and not working so well. The web server is in Chicago and I am in California so it took a day or two to get someone to check on it. The conclusion was the hard drive had been fried. When the weekend ended, we sent the disk to a disk repair place. They took a look at it and a couple days later said that they couldn’t do anything. The heads that normally read and write data on a hard drive by floating over the magnetized platter had crashed right into it. While the computer was giving us error messages it was also scratching away a hole in the platter. It got so thin that you could see through it. This was just in one spot on the disk, though, so we tried calling the famed Drive Savers to see if they could recover the rest. They seemed to think they wouldn’t have any better luck. (Please, plase, please, tell me if you know someplace to try.) I hadn’t backed the disk up for at least a year (in fairness, I was literally going to back it up when I found it giving off error messages) and the thought of the loss of all that data was crushing.