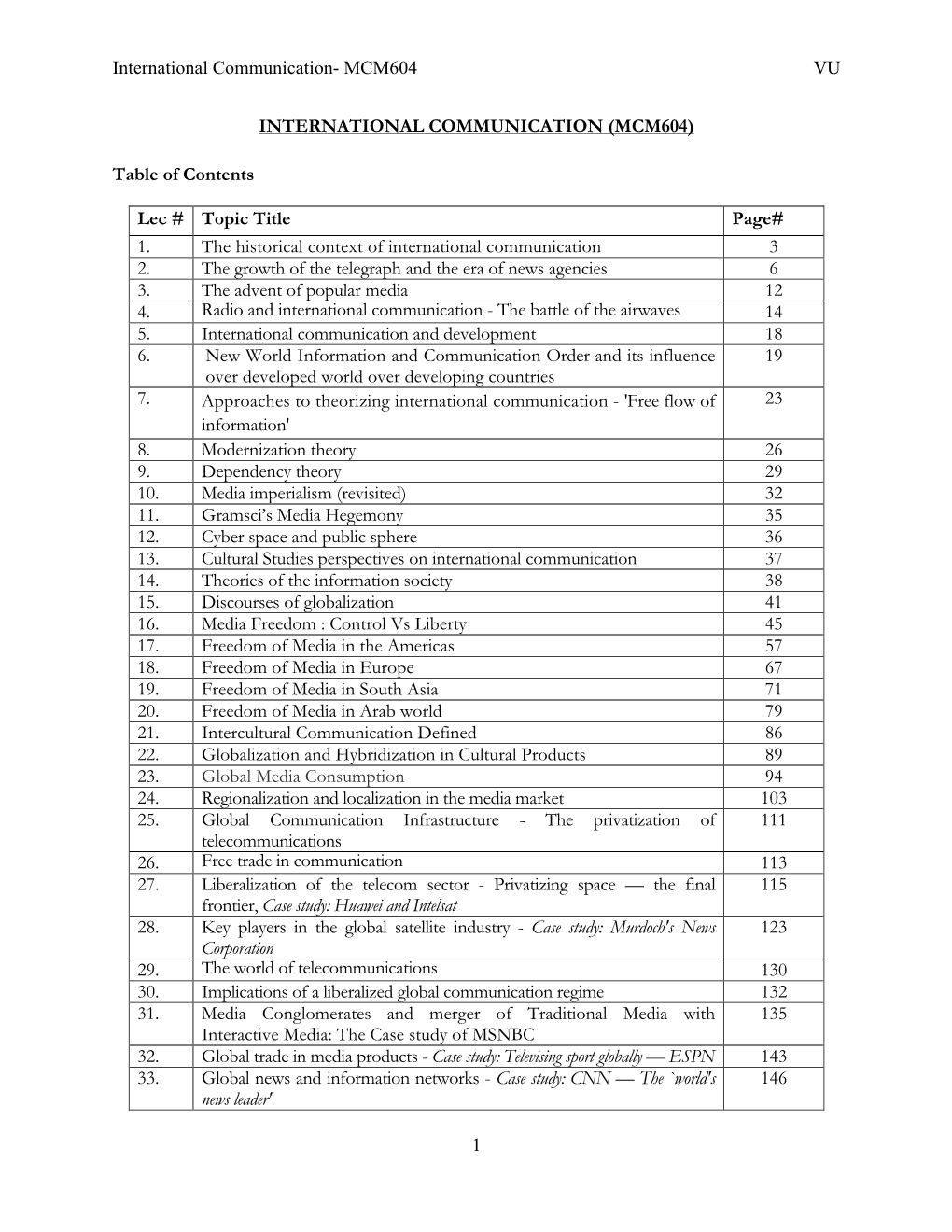

International Communication- MCM604 VU

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Finding Aid to the Historymakers ® Video Oral History with Douglas Holloway

Finding Aid to The HistoryMakers ® Video Oral History with Douglas Holloway Overview of the Collection Repository: The HistoryMakers®1900 S. Michigan Avenue Chicago, Illinois 60616 [email protected] www.thehistorymakers.com Creator: Holloway, Douglas V., 1954- Title: The HistoryMakers® Video Oral History Interview with Douglas Holloway, Dates: December 13, 2013 Bulk Dates: 2013 Physical 9 uncompressed MOV digital video files (4:10:46). Description: Abstract: Television executive Douglas Holloway (1954 - ) is the president of Ion Media Networks, Inc. and was an early pioneer of cable television. Holloway was interviewed by The HistoryMakers® on December 13, 2013, in New York, New York. This collection is comprised of the original video footage of the interview. Identification: A2013_322 Language: The interview and records are in English. Biographical Note by The HistoryMakers® Television executive Douglas V. Holloway was born in 1954 in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. He grew up in the inner-city Pittsburgh neighborhood of Homewood. In 1964, Holloway was part of the early busing of black youth into white neighborhoods to integrate Pittsburgh schools. In 1972, he entered Northeastern University in Boston, Massachusetts as a journalism major. Then, in 1974, Holloway transferred to Emerson College, and graduated from there in 1975 with his B.S. degree in mass communications and television production. In 1978, he received his M.B.A. from Columbia University with an emphasis in marketing and finance. Holloway was first hired in a marketing position with General Foods (later Kraft Foods). He soon moved into the television and communications world, and joined the financial strategic planning team at CBS in 1980. -

Murdoch's Global Plan For

CNYB 05-07-07 A 1 5/4/2007 7:00 PM Page 1 TOP STORIES Portrait of NYC’s boom time Wall Street upstart —Greg David cashes in on boom on the red hot economy in options trading Page 13 PAGE 2 ® New Yorkers are stepping to the beat of Dancing With the Stars VOL. XXIII, NO. 19 WWW.NEWYORKBUSINESS.COM MAY 7-13, 2007 PRICE: $3.00 PAGE 3 Times Sq. details its growth, worries Murdoch’s about the future PAGE 3 global plan Under pressure, law firms offer corporate clients for WSJ contingency fees PAGE 9 421-a property tax Times, CNBC and fight heads to others could lose Albany; unpacking out to combined mayor’s 2030 plan Fox, Dow Jones THE INSIDER, PAGE 14 BY MATTHEW FLAMM BUSINESS LIVES last week, Rupert Murdoch, in a ap images familiar role as insurrectionist, up- RUPERT MURDOCH might bring in a JOINING THE PARTY set the already turbulent media compatible editor for The Wall Street Journal. landscape with his $5 billion offer for Dow Jones & Co. But associ- NEIL RUBLER of Vantage Properties ates and observers of the News media platform—including the has acquired several Corp. chairman say that last week planned Fox Business cable chan- thousand affordable was nothing compared with what’s nel—and take market share away housing units in the in store if he acquires the property. from rivals like CNBC, Reuters past 16 months. Campaign staffers They foresee a reinvigorated and the Financial Times. trade normal lives for a Dow Jones brand that will combine Furthermore, The Wall Street with News Corp.’s global assets to Journal would vie with The New chance at the White NEW POWER BROKERS House PAGE 39 create the foremost financial news York Times to shape the national and information provider. -

Media Ownership Chart

In 1983, 50 corporations controlled the vast majority of all news media in the U.S. At the time, Ben Bagdikian was called "alarmist" for pointing this out in his book, The Media Monopoly . In his 4th edition, published in 1992, he wrote "in the U.S., fewer than two dozen of these extraordinary creatures own and operate 90% of the mass media" -- controlling almost all of America's newspapers, magazines, TV and radio stations, books, records, movies, videos, wire services and photo agencies. He predicted then that eventually this number would fall to about half a dozen companies. This was greeted with skepticism at the time. When the 6th edition of The Media Monopoly was published in 2000, the number had fallen to six. Since then, there have been more mergers and the scope has expanded to include new media like the Internet market. More than 1 in 4 Internet users in the U.S. now log in with AOL Time-Warner, the world's largest media corporation. In 2004, Bagdikian's revised and expanded book, The New Media Monopoly , shows that only 5 huge corporations -- Time Warner, Disney, Murdoch's News Corporation, Bertelsmann of Germany, and Viacom (formerly CBS) -- now control most of the media industry in the U.S. General Electric's NBC is a close sixth. Who Controls the Media? Parent General Electric Time Warner The Walt Viacom News Company Disney Co. Corporation $100.5 billion $26.8 billion $18.9 billion 1998 revenues 1998 revenues $23 billion 1998 revenues $13 billion 1998 revenues 1998 revenues Background GE/NBC's ranks No. -

Rp. 149.000,- Rp

Indovision Basic Packages SUPER GALAXY GALAXY VENUS MARS Rp. 249.000,- Rp. 179.000,- Rp. 149.000,- Rp. 149.000,- Animax Animax Animax Animax AXN AXN AXN AXN BeTV BeTV BeTV BeTV Channel 8i Channel 8i Channel 8i Channel 8i E! Entertainment E! Entertainment E! Entertainment E! Entertainment FOX FOX FOX FOX FOXCrime FOXCrime FOXCrime FOXCrime FX FX FX FX Kix Kix Kix Kix MNC Comedy MNC Comedy MNC Comedy MNC Comedy MNC Entertainment MNC Entertainment MNC Entertainment MNC Entertainment One Channel One Channel One Channel One Channel Sony Entertainment Television Sony Entertainment Television Sony Entertainment Television Sony Entertainment Television STAR World STAR World STAR World STAR World Syfy Universal Syfy Universal Syfy Universal Syfy Universal Thrill Thrill Thrill Thrill Universal Channel Universal Channel Universal Channel Universal Channel WarnerTV WarnerTV WarnerTV WarnerTV Al Jazeera English Al Jazeera English Al Jazeera English Al Jazeera English BBC World News BBC World News BBC World News BBC World News Bloomberg Bloomberg Bloomberg Bloomberg Channel NewsAsia Channel NewsAsia Channel NewsAsia Channel NewsAsia CNBC Asia CNBC Asia CNBC Asia CNBC Asia CNN International CNN International CNN International CNN International Euronews Euronews Euronews Euronews Fox News Fox News Fox News Fox News MNC Business MNC Business MNC Business MNC Business MNC News MNC News MNC News MNC News Russia Today Russia Today Russia Today Russia Today Sky News Sky News Sky News Sky News BabyTV BabyTV BabyTV BabyTV Boomerang Boomerang Boomerang Boomerang -

Your Pace Or Mine: Culture, Time and Negotiation

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Institutional Knowledge at Singapore Management University Singapore Management University Institutional Knowledge at Singapore Management University Research Collection School Of Law School of Law 1-2006 Your Pace or Mine: Culture, Time and Negotiation Ian MACDUFF Singapore Management University, [email protected] DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1571-9979.2006.00084.x Follow this and additional works at: https://ink.library.smu.edu.sg/sol_research Part of the Dispute Resolution and Arbitration Commons Citation MACDUFF, Ian. Your Pace or Mine: Culture, Time and Negotiation. (2006). Negotiation Journal. 22, (1), 31-45. Research Collection School Of Law. Available at: https://ink.library.smu.edu.sg/sol_research/879 This Journal Article is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Law at Institutional Knowledge at Singapore Management University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Research Collection School Of Law by an authorized administrator of Institutional Knowledge at Singapore Management University. For more information, please email [email protected]. Published in Negotiation Journal, Volume 22, Issue 1, January 2006, Pages 31-45. http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1571-9979.2006.00084.x Your Pace or Mine? Culture, Time, and Negotiation Ian Macduff This article explores the impact that different perceptions of time may have on cross-cultural negotiations. Beyond obvious issues of punc- tuality and timekeeping, differences may occur in the value placed on the uses of time and the priorities given to past, present, or future ori- entations. -

Freepint Report: Product Review of Factiva

FreePint Report: Product Review of Factiva December 2014 Product Review of Factiva In-depth, independent review of the product, plus links to related resources “...has some 32,000 sources spanning all forms of content of which thousands are not available on the free web. Some source archives go back to 1951...” [SAMPLE] www.freepint.com © Free Pint Limited 2014 Contents Introduction & Contact Details 4 Sources - Content and Coverage 5 Technology - Search and User Interface 8 Technology - Outputs, Analytics, Alerts, Help 18 Value - Competitors, Development & Pricing 29 FreePint Buyer’s Guide: News 33 Other Products 35 About the Reviewer 36 ^ Back to Contents | www.freepint.com - 2 - © Free Pint Limited 2014 About this Report Reports FreePint raises the value of information in the enterprise, by publishing articles, reports and resources that support information sources, information technology and information value. A FreePint Subscription provides customers with full access to everything we publish. Customers can share individual articles and reports with anyone at their organisations as part of the terms and conditions of their license. Some license levels also enable customers to place materials on their intranets. To learn more about FreePint, visit http://www.freepint.com/ Disclaimer FreePint Report: Product Review of Factiva (ISBN 978-1-78123-181-4) is a FreePint report published by Free Pint Limited. The opinions, advice, products and services offered herein are the sole responsibility of the contributors. Whilst all reasonable care has been taken to ensure the accuracy of the publication, the publishers cannot accept responsibility for any errors or omissions. Except as covered by subscriber or purchaser licence agreement, this publication MAY NOT be copied and/or distributed without the prior written agreement of the publishers. -

Latinoamérica, En La Comunicación Mundial

http://dx.doi.org/10.12795/Ambitos.1999-2000.i03-04.03 ÁMBITOS. Nº 3-4. 2º Semestre 1999-1er Semestre 2000 (pp. 45-59) Latinoamérica en la Comunicación Mundial Dra. Mª Antonia Martín Díez Universidad Europea de Madrid Visión genérica de la comunicación en América Latina por medio de diferentes apartados en los que se reflejan desde la dependencia de los Estados Unidos hasta los logros e intentos de desa- rrollar medios de comunicación que busquen y profundicen en las raíces culturales latinoame- ricanas. El surgimiento de grandes grupos autóctonos de comunicación y sus alianzas con gru- pos de los países desarrollados es otro de los aspectos a resaltar. a estructura de la comunicación latinoamericana se encuentra inmersa dentro del sistema internacional de la información1 . En ella encontramos, obviamente, las tendencias de intercambio e interdependencia actuales. LEstas se pueden producir bien como relaciones paralelas (junto a), bien como relaciones opuestas (frente a). Entre las numerosas tendencias que subyacen en la estructura de la comu- nicación latinoamericana cuya investigación nos ha llevado a descubrir, destaca- mos las siguientes: 1-. Regionalización versus globalización. 2-. Poder autónomo versus poder dependiente. 3-. Proteccionismo versus librecambismo. 4-. Estatismo versus privatización. 5-. Civilización occidental versus otras civilizaciones. 6-. Culturas propias versus cultura norteamericana. 7-. Exposición ideológica directa versus método del entretenimiento. 1 Ver sobre el tema, S. NÚÑEZ DE PRADO y Mª A. MARTÍN, Estructura de la comunicación mundial, Madrid, Univérsitas, pp. 61-78. http://dx.doi.org/10.12795/Ambitos.1999-2000.i03-04.03 46 Latinoamérica en la comunicación mundial Vamos a recorrer cada uno de esos grupos de tendencias: I)-. -

Media Tracking List Edition January 2021

AN ISENTIA COMPANY Australia Media Tracking List Edition January 2021 The coverage listed in this document is correct at the time of printing. Slice Media reserves the right to change coverage monitored at any time without notification. National National AFR Weekend Australian Financial Review The Australian The Saturday Paper Weekend Australian SLICE MEDIA Media Tracking List January PAGE 2/89 2021 Capital City Daily ACT Canberra Times Sunday Canberra Times NSW Daily Telegraph Sun-Herald(Sydney) Sunday Telegraph (Sydney) Sydney Morning Herald NT Northern Territory News Sunday Territorian (Darwin) QLD Courier Mail Sunday Mail (Brisbane) SA Advertiser (Adelaide) Sunday Mail (Adel) 1st ed. TAS Mercury (Hobart) Sunday Tasmanian VIC Age Herald Sun (Melbourne) Sunday Age Sunday Herald Sun (Melbourne) The Saturday Age WA Sunday Times (Perth) The Weekend West West Australian SLICE MEDIA Media Tracking List January PAGE 3/89 2021 Suburban National Messenger ACT Canberra City News Northside Chronicle (Canberra) NSW Auburn Review Pictorial Bankstown - Canterbury Torch Blacktown Advocate Camden Advertiser Campbelltown-Macarthur Advertiser Canterbury-Bankstown Express CENTRAL Central Coast Express - Gosford City Hub District Reporter Camden Eastern Suburbs Spectator Emu & Leonay Gazette Fairfield Advance Fairfield City Champion Galston & District Community News Glenmore Gazette Hills District Independent Hills Shire Times Hills to Hawkesbury Hornsby Advocate Inner West Courier Inner West Independent Inner West Times Jordan Springs Gazette Liverpool -

The Importance of Nonverbal Communication in Business and How Professors at the University of North Georgia Train Students on the Subject

University of North Georgia Nighthawks Open Institutional Repository Honors Theses Honors Program Spring 2018 The mpI ortance of Nonverbal Communication in Business and How Professors at the University of North Georgia Train Students on the Subject Britton Bailey University of North Georgia, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.northgeorgia.edu/honors_theses Part of the Business Commons Recommended Citation Bailey, Britton, "The mporI tance of Nonverbal Communication in Business and How Professors at the University of North Georgia Train Students on the Subject" (2018). Honors Theses. 33. https://digitalcommons.northgeorgia.edu/honors_theses/33 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors Program at Nighthawks Open Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Nighthawks Open Institutional Repository. The Importance of Nonverbal Communication in Business and How Professors at the University of North Georgia Train Students on the Subject A Thesis Submitted to The Faculty of the University of North Georgia In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements of The Degree in Bachelor of Business Administration in Management With Honors Britton G. Bailey Spring 2018 Nonverbal Communication 3 Acknowledgments I would like to thank Dr. Mohan Menon, Dr. Benjamin Garner, and Dr. Stephen Smith for their guidance and advice during the course of this project. Secondly, I would like to thank the many other professors and mentors who have given me advice, not only during the course of this project, but also through my collegiate life. Lastly, I would like to thank Rebecca Bailey, Loren Bailey, Briana Bailey, Kandice Cantrell and countless other friends and family for their love and support. -

Esf-15 Public Information & Warning

ESF-15 PUBLIC INFORMATION & WARNING CONTENTS PAGE I. PURPOSE ESF 15.2 II. SITUATIONS AND ASSUMPTIONS ESF 15.2 A. Situations ESF 15.2 B. Assumptions ESF 15.3 III. WARNING SYSTEMS ESF 15.3 A. General ESF 15.3 B. Primary Warning System ESF 15.4 C. Alternate (redundant) Warning System ESF 15.7 D. Additional Tools for Warning ESF 15.10 E. Vulnerable Populations ESF 15.10 IV. PUBLIC INFORMATION SYSTEM ESF 15.10 A. General ESF 15.10 B. Joint Information System (JIS) ESF 15.11 C. Public Information Coordination Center (PICC) ESF 15.11 D. Interpreters / Functional Needs / Vulnerable Populations ESF 15.12 V. CONCEPT OF OPERATIONS ESF 15.12 A. Operational Time Frames ESF 15.12 VI. ORGANIZATION AND ASSIGNMENT RESPONSIBILITIES ESF 15.14 A. Primary Agencies ESF 15.14 B. Support Agencies ESF 15.15 C. State Support Agency ESF 15.15 D. Federal Support Agency ESF 15.15 VII. DIRECTION AND CONTROL ESF 15.15 VIII. CONTINUITY OF OPERATIONS ESF 15.15 A. General ESF 15.15 B. Alternate site for EOC ESF 15.16 IX. ADMINISTRATION AND LOGISTICS ESF 15.16 X. ESF DEVELOPMENT AND MAINTENANCE ESF 15.16 XI. REFERENCES ESF 15.16 APPENDICES 1. Activation List ESF 15.18 2. Organizational Chart ESF 15.19 3. Media Points of Contact ESF 15.20 4. Format and Procedures for News Releases ESF 15.24 5. Initial Media Advisory on Emergency ESF 15.25 6. Community Bulletin Board Contacts ESF 15.26 7. Interpreters Contact List ESF 15.27 8. Public Information Call Center (PICC) Plan ESF 15.28 9. -

Universidade Federal De Juiz De Fora Faculdade De Comunicação Social Mestrado Em Comunicação

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DE JUIZ DE FORA FACULDADE DE COMUNICAÇÃO SOCIAL MESTRADO EM COMUNICAÇÃO Pedro Augusto Silva Miranda INTIMIDADE MEDIADA: as estratégias narrativas do GloboNews Em Pauta na comunicação com o público Juiz de Fora 2019 Pedro Augusto Silva Miranda INTIMIDADE MEDIADA: as estratégias narrativas do GloboNews Em Pauta na comunicação com o público Dissertação apresentada ao Programa de Pós- graduação em Comunicação, da Universidade Federal de Juiz de Fora como requisito parcial a obtenção do grau de Mestre em Comunicação. Área de concentração: Comunicação e Sociedade. Orientadora: Prof.a Dra. Cláudia de Albuquerque Thomé Juiz de Fora 2019 Ficha catalográfica elaborada através do programa de geração automática da Biblioteca Universitária da UFJF, com os dados fornecidos pelo(a) autor(a) Miranda, Pedro Augusto Silva. Intimidade Mediada : as estratégias narrativas do GloboNews Em Pauta na comunicação com o público / Pedro Augusto Silva Miranda. -- 2019. 173 p. Orientadora: Cláudia de Albuquerque Thomé Dissertação (mestrado acadêmico) - Universidade Federal de Juiz de Fora, Faculdade de Comunicação Social. Programa de Pós Graduação em Comunicação, 2019. 1. Narrativas. 2. Estratégias. 3. TV por assinatura. 4. Telejornalismo. 5. GloboNews Em Pauta. I. Thomé, Cláudia de Albuquerque, orient. II. Título. Dedico este trabalho aos meus pais, Xavier e Maria, e ao meu irmão Junior. Exemplos de coragem, dedicação e amor incondicional. AGRADECIMENTOS Agradeço, primeiramente, a Deus, por permitir que esse momento acontecesse e por ser luz em meio às adversidades dessa caminhada. Obrigado por me fazer acreditar e mostrar que todos os meus sonhos são possíveis. Agradeço a minha família, pai, mãe e irmão, por sempre estarem ao meu lado com muito amor e acreditando em mim e que tudo daria certo. -

Maximising Availability of International Connectivity in Developing Countries: Strategies to Ensure Global Digital Inclusion Acknowledgements

REGULATORY AND MARKET ENVIRONMENT International Telecommunication Union Telecommunication Development Bureau Place des Nations Maximising Availability CH-1211 Geneva 20 OF INTERNATIONAL CONNECTIVITY Switzerland www.itu.int IN DEVELOPING COUNTRIES: STRATEGIES TO ENSURE GLOBAL DIGITAL INCLUSION ISBN: 978-92-61-22491-2 9 7 8 9 2 6 1 2 2 4 9 1 2 Printed in Switzerland Geneva, 2016 INCLUSION GLOBAL DIGITAL TO ENSURE STRATEGIES CONNECTIVITY IN DEVELOPING COUNTRIES: OF INTERNATIONAL AVAILABILITY MAXIMISING Telecommunication Development Sector Maximising availability of international connectivity in developing countries: Strategies to ensure global digital inclusion Acknowledgements The International Telecommunication Union (ITU) would like to thank ITU experts Mike Jensen, Peter Lovelock, and John Ure (TRPC) for the preparation of this report. This report was produced by the ITU Telecommunication Development Bureau (BDT). ISBN: 978-92-61-22481-3 (paper version) 978-92-61-22491-2 (electronic version) 978-92-61-22501-8 (EPUB) 978-92-61-22511-7 (MOBI) Please consider the environment before printing this report. © ITU 2016 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, by any means whatsoever, without the prior written permission of ITU. Table of Contents 1 Introduction and background 1 2 The dynamics of international capacity provision in developing countries 2 2.1 The Global context 2 2.2 International capacity costs 3 2.3 Global transit 4 3 International connectivity provision 5 3.1 Ways and means of enabling international