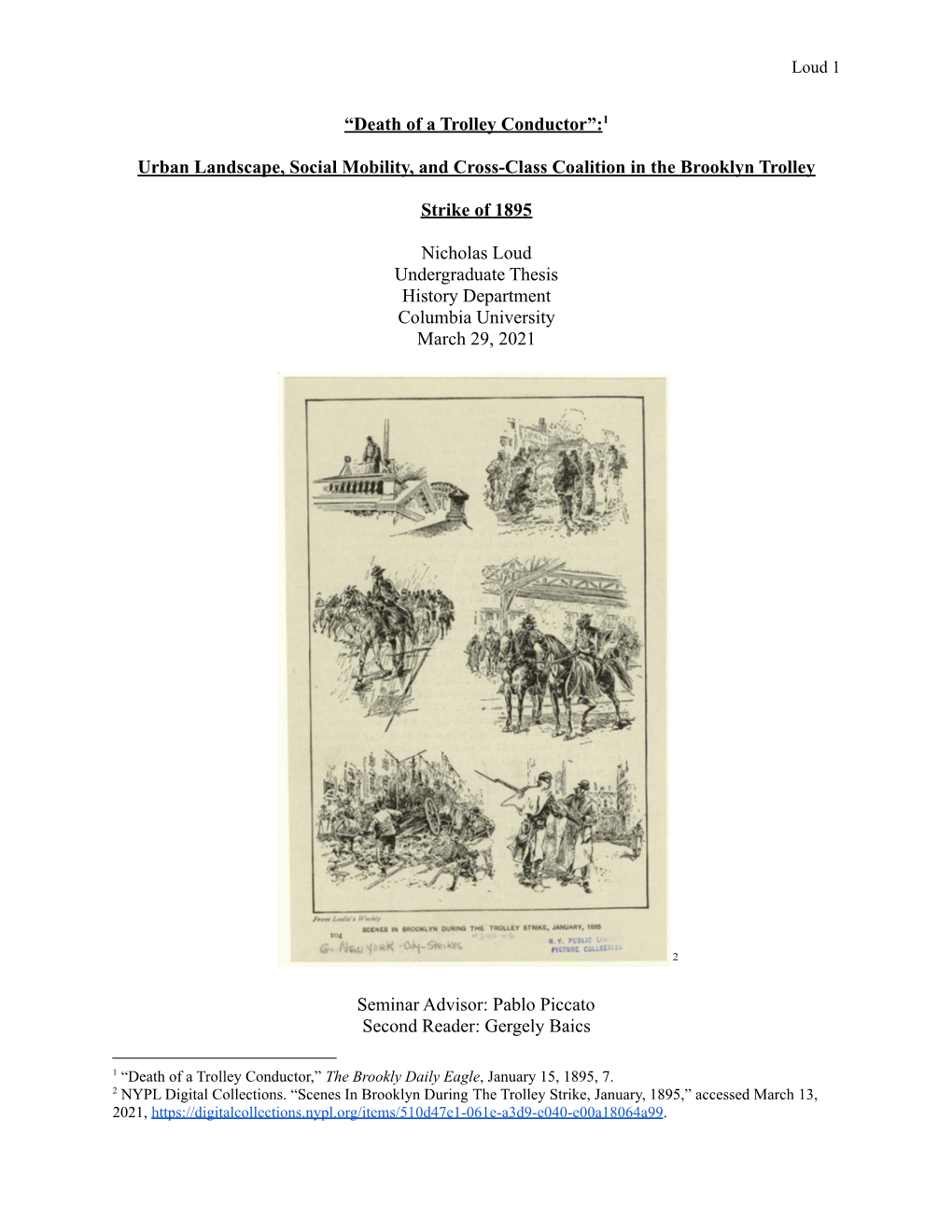

Nicholas Loud Undergraduate History Thesis.Docx

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

RAIL OPERATORS' REPORTING MARKS February 24, 2010 a AA

RAIL OPERATORS' REPORTING MARKS February 24, 2010 A AA ANN ARBOR AAM ASHTOLA AND ALLEGHENY MOUNTAIN AB ATLANTIC AND BIRMINGHAM RAILWAY ABA ATLANTA, BIRMINGHAM AND ATLANTIC ABB AKRON AND BARBERTON BELT RAILROAD ABC ATLANTA, BIRMINGHAM AND COAST ABL ALLEYTON AND BIG LAKE ABLC ABERNETHY-LOUGHEED LOGGING COMPANY ABMR ALBION MINES RAILWAY ABR ARCADIA AND BETSEY RIVER ABS ABILENE AND SOUTHERN ABSO ABBEVILLE SOUTHERN RAILWAY ABYP ALABAMA BY-PRODUCTS CORP. AC ALGOMA CENTRAL ACAL ATLANTA AND CHARLOTTE AIR LINE ACC ALABAMA CONSTRUCTION COMPANY ACE AMERICAN COAL ENTERPRISES ACHB ALGOMA CENTRAL AND HUDSON BAY ACL ATLANTIC COAST LINE ACLC ANGELINA COUNTY LUMBER COMPANY ACM ANACONDA COPPER MINING ACR ATLANTIC CITY RAILROAD ACRR ASTORIA AND COLUMBIA RIVER ACRY AMES AND COLLEGE RAILWAY ACTY AUSTIN CITY RAILROAD ACY AKRON, CANTON AND YOUNGSTOWN ADIR ADIRONDACK RAILWAY ADPA ADDISON AND PENNSYLVANIA RAILWAY AE ALTON AND EASTERN AEC ATLANTIC AND EAST CAROLINA AER ANNAPOLIS AND ELK RIDGE RAILROAD AF AMERICAN FORK RAILROAD AG ATLANTIC AND GULF RAILROAD AGR ALDER GULCH RAILROAD AGP ARGENTINE AND GRAY'S PEAK AGS ALABAMA GREAT SOUTHERN AGW ATLANTIC AND GREAT WESTERN AHR ALASKA HOME RAILROAD AHUK AHUKINI TERMINAL RAILWAY AICO ASHLAND IRON COMPANY AJ ARTEMUS-JELLICO RAILROAD AK ALLEGHENY AND KINZUA RAILROAD AKC ALASKA CENTRAL AKN ALASKA NORTHERN AL ALMANOR ALBL ALAMEDA BELT LINE ALBP ALBERNI PACIFIC ALBR ALBION RIVER RAILROAD ALC ALLEN LUMBER COMPANY ALCR ALBION LUMBER COMPANY RAILROAD ALGC ALLEGHANY CENTRAL (MD) ALLC ALLEGANY CENTRAL (NY) ALM ARKANSAS AND LOUISIANA -

Liicycle PARADE L'abbing Ihkougil PARK PLAZA Fnlkancl THIRTY-FIFTH

-- -- liICYCLE PARADE l'AbbING IHKOUGIl PARK PLAZA FNlKANCl THIRTY-FIFTH ANNUAL REPORT OF THE CITY OF BROOKLYN AND THE FIRST OF THE COUNTY OF KINGS FOR THE YEAR 1895 BROOKLYN PRINTED FOR THE COMMISSIONER THE OFFICIAL LIST. Commissioner, FRANK SQUIER. Deputy Commissioner, HENRY L. PALMER. Secretary, JOHN EDWARD SMITII, General Superintendent, RUDOLPH ULRICH. Landscape Architects, Advisory, OLMSTED, OLMSTED & ELIOT. Paymaster, ROBERT H. SMITH. Assistant Paymaster, OSCAR C. WHEDON. Property and Labor Clerk, WILLIAM A. BOOTH. Stenographer, MAY G. HAMILTON. THECOMMISSIONER~S REPORT OF THE WORK OF THE DURINGTHE YEAR 1895. OFIJICE OF THE COMMISSIONEROF THE DEPARTMENTOF PARKS, " LITCHFIELD MANSION,"PROSPECT PARK, BROOI~LYN,January st, 1896. To the Honorable, the Common Council : GENTLEMEN-I have the honor herewith to submit to your Honorable Body my Annual Report concerning the care of the Parks and Parkways of the City of Brooklyn and of the County of Kings, which have been under my charge during the year 1895. There have been more than the usual developments in the way of care and improvement of the parks, and in addition there has been an acquisition of property which doubles the area of park lands existing at the beginning of the year, thus placing the city somewhat on a par with other great cities of the country. Steps have also been taken in the direction of increas- ing the pleasure drives, and the County now owns nearly all the property needed for the creation of the most charming drive in the world-the Hay Ridge Parkway, or, as it is popularly called, the Shore Drive. -

The Bulletin RAYMOND R

ERA BULLETIN — APRIL, 2016 The Bulletin Electric Railroaders’ Association, Incorporated Vol. 59, No. 4 April, 2016 The Bulletin RAYMOND R. BERGER, 1941-2016 Published by the Electric by Eric R. Oszustowicz Railroaders’ Association, Incorporated, PO Box On March 1, 2016, Raymond R. Berger corresponded regularly. In addition, the pho- 3323, New York, New York 10163-3323. passed away at age 74. He was an ERA tographic results of his travels were shared member since 1958. Ray will be missed by through countless presentations at which he us all. Ray was on the ERA’s Board of Direc- would educate attendees through meticulous For general inquiries, tors for many years and also served for a narration regarding the transit systems dis- contact us at bulletin@ time as the Chairman of its New York Divi- played. erausa.org. ERA’s website is sion when it was still operationally independ- Ray was a retired transit professional and www.erausa.org. ent. was a respected member of NYCT’s Division To state that Ray performed work for the of Car Equipment. Think of Ray the next time Editorial Staff: ERA is quite an understate- you ride an R-142 or R- Editor-in-Chief: ment. All who perform work 142A since he contributed to Bernard Linder Tri-State News and for the ERA do so on a their basic design. Commuter Rail Editor: strictly volunteer basis. Ray Ray was a religious man. Ronald Yee was an extremely busy indi- He attained secular mem- North American and World vidual with many interests, bership in the Third Order of News Editor: Alexander Ivanoff but he was always available St. -

The Street Railway Journal

; OCT 2 1890 I NEW YORK: I I CHICAGO* ) Vol. i. liberty Street.) October, 1885. I 32 \12 Lakeside Building./ NO. 12. President Calvin A. Richards. advance of the times; to do that, has now family circle engrossing all his time out- become a motto with him and guides him side of business hours. The subject of our sketch, President of in all his railroad transactions. the American Street Railway Association The railroad which he represents is now The Car Timer's Last Gasp. and of the Metropolitan Railroad, of Bos- probably the largest street railroad in the ton, was born in Dorchester Mass., fifty- world in equipment, in miles of track, and "Timers is like machines," said a gray, seven years ago, and received his educa- in the number of passengers carried. oracular driver on the Third avenue line. tion in the public schools of "Timers is like machines. Boston. His business train- They gets so used to timin' ing was received with his that they can't let up, but father, an old and honored keeps along at it sleepin' or merchant of Boston. wakin'. If some o' them Mr. Richards was en- fellers was a-dyin' they'd gaged in business, him- want to spot the ticker afore self, until 1872, when he peggin' out, just to see if retired from active work, death was up to the scratch. and with his family, made Why, there was Pete Long a long visit to Europe. On —the allfiredest particular- his return from abroad, he ist man I ever see. -

Pullman Company Archives

PULLMAN COMPANY ARCHIVES THE NEWBERRY LIBRARY Guide to the Pullman Company Archives by Martha T. Briggs and Cynthia H. Peters Funded in Part by a Grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities Chicago The Newberry Library 1995 ISBN 0-911028-55-2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ............................................. v - xii ... Access Statement ............................................ xiii Record Group Structure ..................................... xiv-xx Record Group No . 01 President .............................................. 1 - 42 Subgroup No . 01 Office of the President ...................... 2 - 34 Subgroup No . 02 Office of the Vice President .................. 35 - 39 Subgroup No . 03 Personal Papers ......................... 40 - 42 Record Group No . 02 Secretary and Treasurer ........................................ 43 - 153 Subgroup No . 01 Office of the Secretary and Treasurer ............ 44 - 151 Subgroup No . 02 Personal Papers ........................... 152 - 153 Record Group No . 03 Office of Finance and Accounts .................................. 155 - 197 Subgroup No . 01 Vice President and Comptroller . 156 - 158 Subgroup No. 02 General Auditor ............................ 159 - 191 Subgroup No . 03 Auditor of Disbursements ........................ 192 Subgroup No . 04 Auditor of Receipts ......................... 193 - 197 Record Group No . 04 Law Department ........................................ 199 - 237 Subgroup No . 01 General Counsel .......................... 200 - 225 Subgroup No . 02 -

The Street Railway Journal

Vol. X No. 3. The Trolley Cars in Bremen. The length of the line is 6.21 miles, of which 4 miles is laid with single track, and 2.21 miles with double track. Among the progressive communities of Northern The entire system consists of two lines, one running from Germany, the flourishing city of Bremen, with its white the Burgerpark to Freihafen, and the other from Horn to houses and well kept streets, was one of the earliest to the Hohen Thor, the lines from the railroad station to the adopt electric traction. The steady horse car had for corner of the Langen and Kaisers Strassen being common many years carried the staid burgers of the old Hanse to both systems. City by the Weser, along its narrow, picturesque streets, The power station for the generation and supply of crowded with historical memories, when to be a city of the current is located on the Schlachthof, near to the line to principal Hanseatic League meant almost to be a repub- the Burgerpark. It is a brick building constructed in lic. But the expansion of the town by the growing trade three parts, one containing the engine and generator of the world, a goodly part of which has chosen Bremen room, the second the boilers, and the third and smallest FIG. 1. — ELECTRIC CARS PASSING THE MARKET PLACE—BREMEN, GERMANY. as its inlet to the vast markets of the North German ter- the coal bins. It covers 4,777 square feet of ground ritories, determined a beneficial change in transportation space. -

Transportation: Past, Present and Future “From the Curators”

Transportation: Past, Present and Future “From the Curators” Transportationthehenryford.org in America/education Table of Contents PART 1 PART 2 03 Chapter 1 85 Chapter 1 What Is “American” about American Transportation? 20th-Century Migration and Immigration 06 Chapter 2 92 Chapter 2 Government‘s Role in the Development of Immigration Stories American Transportation 99 Chapter 3 10 Chapter 3 The Great Migration Personal, Public and Commercial Transportation 107 Bibliography 17 Chapter 4 Modes of Transportation 17 Horse-Drawn Vehicles PART 3 30 Railroad 36 Aviation 101 Chapter 1 40 Automobiles Pleasure Travel 40 From the User’s Point of View 124 Bibliography 50 The American Automobile Industry, 1805-2010 60 Auto Issues Today Globalization, Powering Cars of the Future, Vehicles and the Environment, and Modern Manufacturing © 2011 The Henry Ford. This content is offered for personal and educa- 74 Chapter 5 tional use through an “Attribution Non-Commercial Share Alike” Creative Transportation Networks Commons. If you have questions or feedback regarding these materials, please contact [email protected]. 81 Bibliography 2 Transportation: Past, Present and Future | “From the Curators” thehenryford.org/education PART 1 Chapter 1 What Is “American” About American Transportation? A society’s transportation system reflects the society’s values, Large cities like Cincinnati and smaller ones like Flint, attitudes, aspirations, resources and physical environment. Michigan, and Mifflinburg, Pennsylvania, turned them out Some of the best examples of uniquely American transporta- by the thousands, often utilizing special-purpose woodwork- tion stories involve: ing machines from the burgeoning American machinery industry. By 1900, buggy makers were turning out over • The American attitude toward individual freedom 500,000 each year, and Sears, Roebuck was selling them for • The American “culture of haste” under $25. -

Draft, Historical Background Report, B.R.T. Central

B.R.T. CENTRAL POWERHOUSE 153 Second Street Brooklyn, New York DRAFT HISTORICAL BACKGROUND REpORT January 2005 Higgins & Quasebarth 270 Lafayette Street New York, NY 10012 (212) 274-9468 INTRODUCTION & SUMMARY 2 This draft report has been compiled by Higgins & Quasebarth for Gowanus Village LLC to explore the historical development of the site to inform the process for the potential redevelopment of the parcel. The documentation included in this report is based on historical map research, various written sources including early newspapers, and correspondence with historians at Metropolitan Transit Authority (MTA). Other possible sources which have not yet been reviewed include the records of MTA, and possibly ConEdison, and the resources available at the Brooklyn Historical Society which has been closed due to construction. Also, an additional site visit and inspection of the existing fabric would be helpful in revealing the amount of historic fabric that remains. 153 Second Street is a monumental, three-story brick powerhouse located immediately east of the Gowanus Canal on Second Street in Brooklyn, New York. The block is bounded by the Gowanus Canal to the west, Third Avenue to the east, to the south by Second Street, and, histOrically, to the north by the First Street Basin, which has been infilled. Constructed between 1900 and 1904, the building was part of the Brooklyn Rapid Transit's Central Powerhouse complex, which fully occupied this block. The north section of the building was demolished between 1938 and 1950. The Central Powerhouse was constructed as part of the Brooklyn Rapid Transit (ERT) electrification project when all of the consolidated Brooklyn surface and elevated railways were electrified. -

How We Got to Coney Island

How We Got to Coney Island .......................... 9627$$ $$FM 06-28-04 08:03:55 PS .......................... 9627$$ $$FM 06-28-04 08:03:55 PS How We Got to Coney Island THE DEVELOPMENT OF MASS TRANSPORTATION IN BROOKLYN AND KINGS COUNTY BRIAN J. CUDAHY Fordham University Press New York 2002 .......................... 9627$$ $$FM 06-28-04 08:03:55 PS Copyright ᭧ 2002 by Fordham University Press All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means— electronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording, or any other—except for brief quotations in printed reviews, without the prior permission of the publisher. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Cudahy, Brian J. How we got to Coney Island : the development of mass transportation in Brooklyn and Kings County / Brian J. Cudahy. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-8232-2208-X (cloth)—ISBN 0-8232-2209-8 (pbk.) 1. Local transit—New York Metropolitan Area—History. 2. Transportation—New York Metropolitan Area—History. 3. Coney Island (New York, N.Y.)—History. I. Title. HE4491.N65 C8 2002 388.4Ј09747Ј23—dc21 2002009084 Printed in the United States of America 02 03 04 05 06 5 4 3 2 1 First Edition .......................... 9627$$ $$FM 06-28-04 08:03:55 PS CONTENTS Foreword vii Preface xiii 1. A Primer on Coney Island and Brooklyn 1 2. Street Railways (1854–1890) 24 3. Iron Piers and Iron Steamboats (1845–1918) 49 4. Excursion Railways (1864–1890) 67 5. Elevated Railways (1880–1890) 104 6. -

Brooklyn Rapid Transit Company (BRT) Central Power Station Engine House

DESIGNATION REPORT Brooklyn Rapid Transit Company (BRT) Central Power Station Engine House Landmarks Preservation Designation Report Designation List 515 Commission BRT Engine House LP-2639 October 29, 2019 DESIGNATION REPORT Brooklyn Rapid Transit Company (BRT) Central Power Station Engine House LOCATION Borough of Brooklyn 153 2nd Street (aka 322 Third Avenue, 340 Third Avenue) LANDMARK TYPE Individual SIGNIFICANCE The monumental BRT Central Power Station Engine House is a prominent reminder of the era when the Gowanus Canal was a significant inland waterway and the Gowanus neighborhood was a major industrial center. Landmarks Preservation Designation Report Designation List 515 Commission BRT Engine House LP-2639 October 29, 2019 “New Central Station,” The Street Railway Journal, February 14, 1903 LANDMARKS PRESERVATION COMMISSION COMMISSIONERS Lisa Kersavage, Executive Director Sarah Carroll, Chair Mark Silberman, General Counsel Frederick Bland, Vice Chair Timothy Frye, Director of Special Projects and Diana Chapin Strategic Planning Wellington Chen Kate Lemos McHale, Director of Research Michael Devonshire Cory Herrala, Director of Preservation Michael Goldblum John Gustafsson REPORT BY Anne Holford-Smith Matthew A. Postal, Research Department Everardo Jefferson Jeanne Lutfy Adi Shamir-Baron EDITED BY Kate Lemos McHale and Margaret Herman Landmarks Preservation Designation Report Designation List 515 Commission BRT Engine House LP-2639 October 29, 2019 3 of 25 Brooklyn Rapid Transit Company (BRT) Central Power Station Engine House 153 2nd Street, Brooklyn Designation List 515 LP-2639 Built: 1901-04 Consulting engineer: Thomas E. Murray Landmark Site: Borough of Brooklyn Tax Map Block 967, Lot 1 in part, consisting of the land beneath the Brooklyn Rapid Transit Company (BRT) Central Power Station Engine House. -

Special Chases Made Several Months Ago

Fifth Avenue, Atlantic Avenue, Liv¬ Return Company.Transfers between the lines at Effect of of ingston Street, Court Street, Joralemon nated Wyckoff arid Myrtle avenues to show cause its franchise End Fulton of this company and the Brooklyn, ( Borough line). pany why settled months ago by advancing the Transfers Street, Bocrum Place, Street, should not be forfeited was reached. King Alfonso Leaves Madrid for Lines Livingston Street. Queens County & Suburban Railroad "South Brooklyn Railroad fares of the subways," said Mr. Levy. Twenty-six .On account Company, President of "At that Paris When the lines of "The Rogers Avenue Line will be op¬ Company,'the Nassau Electric Railroad of the discontinuance of Borough Connolly Queens time 7 cents would have been To-night ; Queen Has Cold B. R. T. twenty-six the erated via Flatbush the Sixteenth Avenue that the board was restrained 600 Avenue, Livingston will line of the explained sufficient to operate the as PARIS, Oct. will At Brooklyn City Railroad Company are Company be continued as hereto¬ system, but 17..King Alfonso Street, Court Street, Joralemon Street, fore. Brooklyn City Railroad Company over from action because of a Fed¬ the interest has now leave for separated from the Brooklyn Rapid Boerum Place. Transfers between the DeKalb the tracks of the South Rail¬ taking been so largely Madrid Paris to-morrow even¬ Brooklyn eral court increased as was Transit system at Avenue.line of this and the way Company this will ex¬ injunction. and expenses so enlarged by ing, originally planned, accord¬ midnight to-night "The St. John's Place line will be op¬ company tend company to a points To-night the results will be: erated via Flatbush Avenue, Livingston Montague Street line of the Brooklyn its Gravesend Avenue line from "This is the case of the company delay I fear it will cost more than 7 ing dispatch from the Spanish Six hundred Joralemon Sixteenth Avenue to Ninth Avenue where we have obtained a writ of pro¬ cents to the capital to-day. -

SEMAPHORE January 2019 the LIST January Meeting Will Be Held on Friday, January 18Th at the Historic Van Bourgondien House in West Babylon

SEMAPHORE January 2019 The LIST January meeting will be held on Friday, January 18th at the Historic Van Bourgondien House in West Babylon. This house is located at 600 Albin Avenue in West Babylon. The LIRR West Babylon Team Yard is located approximately 1/4 mile NW from the house also on Albin Avenue. Immediately adjacent to the house are soccer fields with a large parking lot for our use. Parking is also on site at the rear of the house down a long driveway. Albin Avenue is just off Arnold Avenue. Arnold Avenue begins at Route 109 on the north, just south of Sunrise Highway and on the south end it is off Great East Neck Road. The Meeting starts at 8:00pm. THIS MONTH: Mr. Philip Eng, President of the Long Island Rail Road will be our guest presenter for the January meeting. Mr. Eng will provide an informative look inside the LIRR of today, and many of its capital improvement projects. IN THIS ISSUE: Page 2 LIST Order Form Page 3 LIST Happenings Page 4 LIRR Modeler Page 5 LIRR News Page 6, 7 & 8 B R T Street Car R.P.O. Service, Part 1 Page 9 Upcoming Events For regular updates and other important information, visit the Chapter website at: LIST-NRHS.org The Chapter mailing address is: LIST—NRHS P O Box 507 Babylon, New York 11702-0507 Page 2 SEMAPHORE The following price list is for LIST members only! #________LIRR Main Line East by D. Morrison *new book @$18 each Total _______ #________LIRR Trackside with Matt Herson by M.