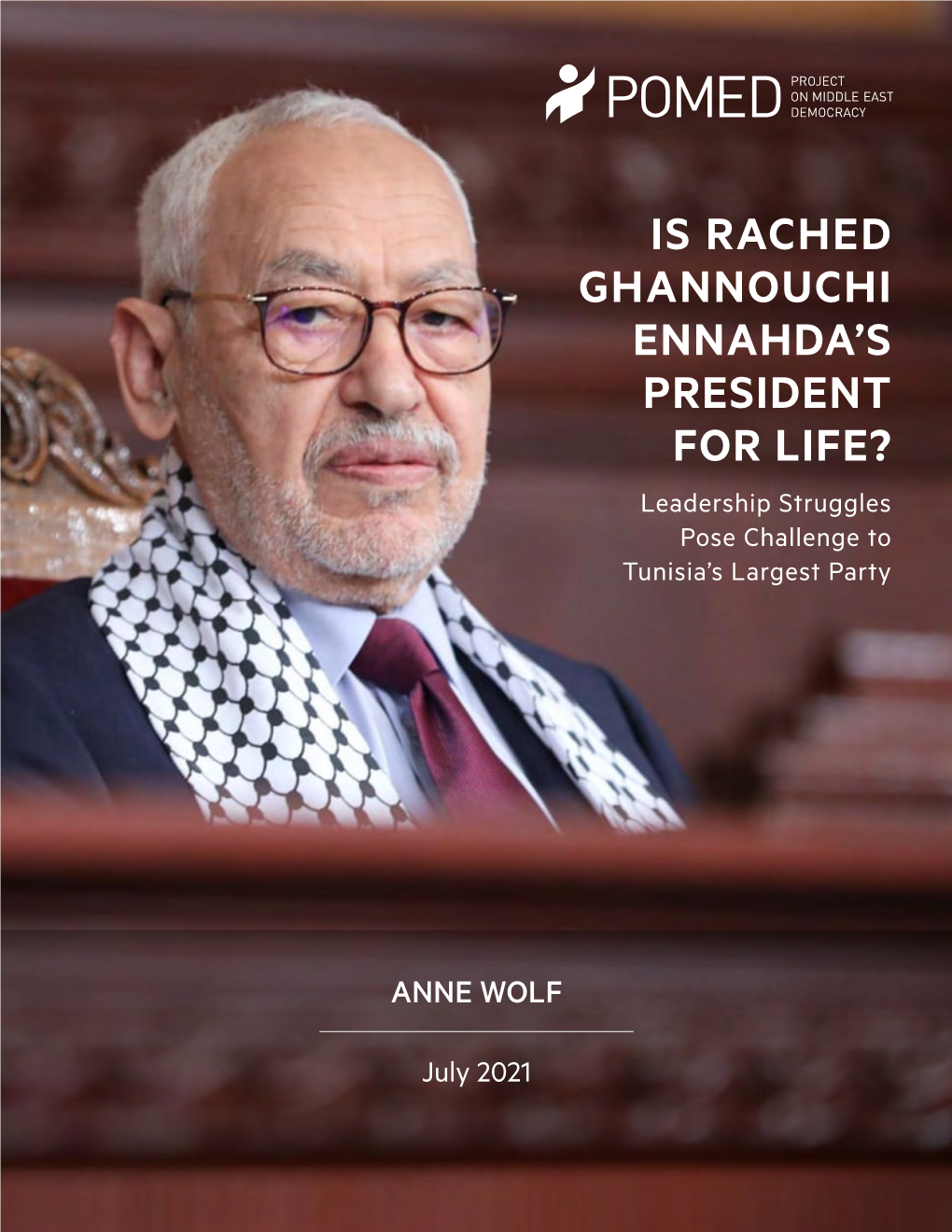

Is Rached Ghannouchi Ennahda's President for Life?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ennahda's Approach to Tunisia's Constitution

BROOKINGS DOHA CENTER ANALYSIS PAPER Number 10, February 2014 CONVINCE, COERCE, OR COMPROMISE? ENNAHDA’S APPROACH TO TUNISIA’S CONSTITUTION MONICA L. MARKS B ROOKINGS The Brookings Institution is a private non-profit organization. Its mission is to conduct high- quality, independent research and, based on that research, to provide innovative, practical recommendations for policymakers and the public. The conclusions and recommendations of any Brookings publication are solely those of its author(s) and do not reflect the views of the Institution, its management, or its scholars. Copyright © 2014 THE BROOKINGS INSTITUTION 1775 Massachusetts Avenue, N.W. Washington, D.C. 20036 U.S.A. www.brookings.edu BROOKINGS DOHA CENTER Saha 43, Building 63, West Bay, Doha, Qatar www.brookings.edu/doha TABLE OF C ONN T E T S I. Executive Summary ............................................................................................................1 II. Introduction ......................................................................................................................3 III. Diverging Assessments .................................................................................................4 IV. Ennahda as an “Army?” ..............................................................................................8 V. Ennahda’s Introspection .................................................................................................11 VI. Challenges of Transition ................................................................................................13 -

President for Life, and Then Some - Nytimes.Com Page 1 of 2

Letter from Africa - President for Life, and Then Some - NYTimes.com Page 1 of 2 • Reprints This copy is for your personal, noncommercial use only. You can order presentation-ready copies for distribution to your colleagues, clients or customers here or use the "Reprints" tool that appears next to any article. Visit www.nytreprints.com for samples and additional information. Order a reprint of this article now. May 11, 2010 President for Life, and Then Some By HOWARD W. FRENCH In the months before his death in 1993 at the age of 88 (or, as widely rumored, as old as 100) and after 33 years in power, the president of Ivory Coast, Félix Houphouët-Boigny, fondly repeated a formula he had once announced publicly to the nation. “A king of the Baoulé has no right to know the identity of his successor,” he is reported to have said. Mr. Houphouët-Boigny may have belonged to royal lineage, but critics said he seemed to be forgetting that the Baoulé were only one of Ivory Coast’s 50 or so ethnic groups, and that he was the president of a would-be modern country. Few were fooled about the old leader’s real intention to rule as president for life, come what may in his aftermath. And the aftermath in Ivory Coast has indeed been grim. West Africa’s most prosperous country has been ripped apart by a civil war whose roots trace directly back to the contested circumstances of his succession, and the old regime has been replaced by a predatory authoritarianism under new leaders determined to hang on at all costs. -

To Download Senator Rubio's Speech Transcript

Remarks as Delivered to the Ronald Reagan Institute on April 30, 2019 By Senator Marco Rubio Thank you very much. Thank you, Fred, for inviting me, for introducing me, that’s very kind. I want to thank John Heubusch, Roger Zakheim, Rachel Hoff, and your colleagues at the Institute for giving me this opportunity and for organizing this event to mark the 35th anniversary of that speech, which you just saw a snippet of a moment ago. I wanted to spend today with you doing 3 things. The first, I wanted to talk about the historic significance of that speech, not just to U.S.- China relations, but to the cause of freedom and liberty around the world. Then I wanted to turn to the complex and challenging relationship today between China in the 21st century and our country. And third, some of the difficult choices we face with regards to that relationship. Let’s talk first about the speech. Some of you here today probably don’t remember that speech very well in 1984. I would have been in 8th grade. Actually, April 1984, I would have been in 7th grade. I remember that year only because it was Dan Marino’s second year and the Dolphins were a football team. But we’re coming back. Many people who work for me weren’t even born in 1984. But it was a part, as you said, of that historic six-day visit, and it was directed at the Chinese people. And the speech was typical Reagan. It overflowed with hope and optimism. -

Middle East Brief, No

Judith and Sidney Swartz Director and Professor of Politics Islamists in Power and Women’s Rights: Shai Feldman Associate Director The Case of Tunisia Kristina Cherniahivsky Charles (Corky) Goodman Professor Carla B. Abdo-Katsipis of Middle East History and Associate Director for Research Naghmeh Sohrabi uch scholarship has been devoted to the question Myra and Robert Kraft Professor Mof Islamist governance, its compatibility with of Arab Politics Eva Bellin democracy, and its sociopolitical implications for women. Henry J. Leir Professor of the Some assert that Islamists cannot be in support of Economics of the Middle East democracy, and women who support democracy would not Nader Habibi support Islamists, as traditional Muslim law accords women Renée and Lester Crown Professor 1 of Modern Middle East Studies fewer rights than men. In the context of the 2010-11 Jasmine Pascal Menoret Revolution in Tunisia, many asked whether Tunisian Senior Fellows women would lose rights, particularly those concerning Abdel Monem Said Aly, PhD 2 Kanan Makiya personal status and family law, when the Islamist political party Ennahda won 41 percent of the votes in the 2011 Goldman Senior Fellow Khalil Shikaki, PhD Constituent Assembly elections and maintained a significant 3 Research Fellow proportion of seats in subsequent elections. Monica Marks David Siddhartha Patel, PhD elaborates on this concern, explaining that those opposed Marilyn and Terry Diamond to Ennahda believed that it would “wage a war against Junior Research Fellow Mohammed Masbah, PhD women’s rights, mandate the hijab, and enforce a separate Neubauer Junior Research Fellow sphere ethos aimed at returning Tunisia’s feminists back to Serra Hakyemez, PhD their kitchens.”4 Junior Research Fellows Jean-Louis Romanet Perroux, PhD This Brief argues that Ennahda’s inclusion in Tunisia’s government has had Ahmad Shokr, PhD a counterintuitive impact on gender-based progress in the country. -

About Tunisia's “Muslim Democrats”?

Crown Family Director Professor of the Practice in Politics Gary Samore What Is “Muslim” about Tunisia’s “Muslim Director for Research Charles (Corky) Goodman Professor Democrats”? of Middle East History Naghmeh Sohrabi Associate Director Andrew F. March Kristina Cherniahivsky Associate Director for Research t the end of its 2016 annual party congress, held in David Siddhartha Patel AHammamet, Tunisia, the traditionally Islamist party Myra and Robert Kraft Professor Ennahda formally declared that the label “political Islam” of Arab Politics Eva Bellin “does not express the essence of its current identity nor Founding Director [does it] reflect the substance of its future vision.” Their Professor of Politics statement continued: “Ennahda believes its work to be within Shai Feldman an authentic endeavor to form a broad trend of Muslim Henry J. Leir Professor of the Economics of the Middle East democrats who reject any contradiction between the values Nader Habibi of Islam and those of modernity.”1 The party portrayed the Renée and Lester Crown Professor change in its identity as driven by political realities and by of Modern Middle East Studies Pascal Menoret the experience of five years of democratic transition: “We Founding Senior Fellows discovered the difference between belief in abstract principles Abdel Monem Said Aly like freedom and democracy, for which we had paid a high Khalil Shikaki price over decades, and the transformation of those principles Goldman Faculty Leave Fellow Andrew March into tangible political achievements, following -

Islam and Politics in Tunisia

Islam and Politics in Tunisia How did the Islamist party Ennahda respond to the rise of Salafism in post-Arab Spring Tunisia and what are possible ex- planatory factors of this reaction? April 2014 Islam and Politics in a Changing Middle East Stéphane Lacroix Rebecca Koch Paris School of© International Affairs M.A. International Security Student ID: 100057683 [email protected] Words: 4,470 © The copyright of this paper remains the property of its author. No part of the content may be repreoduced, published, distributed, copied or stored for public use without written permission of the author. All authorisation requests should be sent to [email protected] Table of Contents 1. Introduction ............................................................................................................. 3 2. Definitions and Theoretical Framework ............................................................... 4 3. Analysis: Ennahda and the Tunisian Salafi movements ...................................... 7 3.1 Ennahda ........................................................................................................................ 7 3.2 Salafism in Tunisia ....................................................................................................... 8 3.3 Reactions of Ennahda to Salafism ................................................................................ 8 4. Discussion ................................................................................................................ 11 5. Conclusion -

Ennahda, Salafism and the Tunisian Transition

religions Article From Victim to Hangman? Ennahda, Salafism and the Tunisian Transition Francesco Cavatorta 1,*,† and Stefano Torelli 2,† 1 Department of Political Science, Laval University, Quebec, QC G1V 0A6, Canada 2 Italian Institute for International Political Studies (ISPI), 20121 Milan, Italy; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] † We are very grateful to the three referees whose insightful comments have improved the manuscript considerably. All errors remain of course our own. Abstract: The article revisits the notion of post-Islamism that Roy and Bayat put forth to investigate its usefulness in analysing the Tunisian party Ennahda and its role in the Tunisian transition. The article argues that the notion of post-Islamism does not fully capture the ideological and political evolution of Islamist parties, which, despite having abandoned their revolutionary ethos, still compete in the political arena through religious categories that subsume politics to Islam. It is only by taking seriously these religious categories that one can understand how Ennahda dealt with the challenge coming from Salafis. Keywords: political Islam; Tunisia; Salafism; Ennahda democratization 1. Introduction Political Islam has been a prominent research topic for the last three decades and the literature on it is as impressive as it is broad. While it is impossible to do full justice Citation: Cavatorta, Francesco, and to how scholars have approached the topic, there are three clusters of research that can Stefano Torelli. 2021. From Victim to be identified. First is the ever-present debate about the compatibility between Islam Hangman? Ennahda, Salafism and the and democracy, which informs the way Islamist parties are analysed (Schwedler 2011). -

Islamism After the Arab Spring: Between the Islamic State and the Nation-State the Brookings Project on U.S

Islamism after the Arab Spring: Between the Islamic State and the nation-state The Brookings Project on U.S. Relations with the Islamic World U.S.-Islamic World Forum Papers 2015 January 2017 Shadi Hamid, William McCants, and Rashid Dar The Brookings Institution is a nonprofit organization devoted to independent research and policy solutions. Its mission is to conduct high-quality, independent research and, based on that research, to provide in- novative, practical recommendations for policymakers and the public. The conclusions and recommendations of any Brookings publication are solely those of its author(s), and do not reflect the views of the Institu- tion, its management, or its other scholars. Project on U.S. Relations with the Islamic World Center for Middle East Policy at Brookings Brookings recognizes that the value it provides to any supporter is in its absolute commitment to quality, 1775 Massachusetts Avenue, NW independence and impact. Activities supported by its Washington, DC 20036 donors reflect this commitment and the analysis and recommendations are not determined by any donation. www.brookings.edu/islamic-world STEERING n 2015, we returned to Doha for the views of the participants of the work- COMMITTEE the 12th annual U.S.-Islamic World ing groups or the Brookings Institution. MArtiN INDYK Forum. Co-convened annually by Select working group papers will be avail- Executive Ithe Brookings Project on U.S. Relations able on our website. Vice President with the Islamic World and the State of Brookings Qatar, the Forum is the premier inter- We would like to take this opportunity BRUCE JONES national gathering of leaders in govern- to thank the State of Qatar for its sup- Vice President ment, civil society, academia, business, port in convening the Forum with us. -

Will Xi Jinping Succeed?

1 Will Xi Jinping Succeed? William H. Overholt I want to offer you a way of understanding China and a very different way of viewing its current leadership. China is the latecomer of a group of Asian miracle economies. It faces a turning point shared by all the Asian miracles, a crisis of success. These crises of success are caused by complexity. Economic success creates a highly differentiated society. The extraordinary complexity of a modern economy can’t be managed from the offices of the top leaders. Likewise, the social complexity requires different political management. The crisis of success A crisis of success is a moment in development of a successful business or a country where continued success requires organizational transformation. Think of an entrepreneur who invents a cool widget and the business takes off, managed as the entourage of that one successful inventor. Soon the point comes where a simple business becomes complicated. It needs to list 1 2 on the stock exchange. It needs professional accounting and professional human resources management. It needs a board of directors and a public rule book. It requires an organizational transformation, and its future success or failure depends on successful transformation. Call it an Elon Musk moment. Xi Jinping’s job is to manage China’s Elon Musk moment. These crises of success share certain characteristics. Like South Korea and Taiwan in the 1980s China finds itself overleveraged, threatened by debt, bubbles, inflation and bankruptcies. The big companies find themselves indebted and unprofitable. Politics also grows more complex, with rising demonstrations and powerful interest groups demanding control over policies. -

Re-Thinking Secularism in Post-Independence Tunisia

The Journal of North African Studies ISSN: 1362-9387 (Print) 1743-9345 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/fnas20 Re-thinking secularism in post-independence Tunisia Rory McCarthy To cite this article: Rory McCarthy (2014) Re-thinking secularism in post-independence Tunisia, The Journal of North African Studies, 19:5, 733-750, DOI: 10.1080/13629387.2014.917585 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13629387.2014.917585 Published online: 12 May 2014. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 465 View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=fnas20 Download by: [Rory McCarthy] Date: 15 December 2015, At: 02:37 The Journal of North African Studies, 2014 Vol. 19, No. 5, 733–750, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13629387.2014.917585 Re-thinking secularism in post- independence Tunisia Rory McCarthy* St Antony’s College, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK The victory of a Tunisian Islamist party in the elections of October 2011 seems a paradox for a country long considered the most secular in the Arab world and raises questions about the nature and limited reach of secularist policies imposed by the state since independence. Drawing on a definition of secularism as a process of defining, managing, and intervening in religious life by the state, this paper identifies how under Habib Bourguiba and Zine al-Abidine Ben Ali the state sought to subordinate religion and to claim the sole right to interpret Islam for the public in an effort to win the monopoly over religious symbolism and, with it, political control. -

Political Islam: a 40 Year Retrospective

religions Article Political Islam: A 40 Year Retrospective Nader Hashemi Josef Korbel School of International Studies, University of Denver, Denver, CO 80208, USA; [email protected] Abstract: The year 2020 roughly corresponds with the 40th anniversary of the rise of political Islam on the world stage. This topic has generated controversy about its impact on Muslims societies and international affairs more broadly, including how governments should respond to this socio- political phenomenon. This article has modest aims. It seeks to reflect on the broad theme of political Islam four decades after it first captured global headlines by critically examining two separate but interrelated controversies. The first theme is political Islam’s acquisition of state power. Specifically, how have the various experiments of Islamism in power effected the popularity, prestige, and future trajectory of political Islam? Secondly, the theme of political Islam and violence is examined. In this section, I interrogate the claim that mainstream political Islam acts as a “gateway drug” to radical extremism in the form of Al Qaeda or ISIS. This thesis gained popularity in recent years, yet its validity is open to question and should be subjected to further scrutiny and analysis. I examine these questions in this article. Citation: Hashemi, Nader. 2021. Political Islam: A 40 Year Keywords: political Islam; Islamism; Islamic fundamentalism; Middle East; Islamic world; Retrospective. Religions 12: 130. Muslim Brotherhood https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12020130 Academic Editor: Jocelyne Cesari Received: 26 January 2021 1. Introduction Accepted: 9 February 2021 Published: 19 February 2021 The year 2020 roughly coincides with the 40th anniversary of the rise of political Islam.1 While this trend in Muslim politics has deeper historical and intellectual roots, it Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral was approximately four decades ago that this subject emerged from seeming obscurity to with regard to jurisdictional claims in capture global attention. -

Everyday Life

Everyday Life The North Korean people live under a strict communist regime. They have no say in how their country is managed. The central government controls nearly every aspect of life in the country. Most jobs don’t have salaries. Food and clothing are mostly provided by the government. People who do have a job with a paycheck earn around $1,500 per year. The majority of North Korean people are very poor. They don’t have things like washing machines, fridges, or even bicycles. Practicing a religion is not allowed as the state sees it as a threat. Instead, children are raised to worship Kim Il Sung, “the President for life”. There are over 34,000 statues of Kim Il Sung in North Korea, and all wedding ceremonies must take place in front of one. Portraits of Kim Il Sung and Kim Jong Il can be found pretty much everywhere. All citizens must hang these portraits, which are provided by the government. Once a month, the police come over and check whether the portraits are still hanging and properly taken care of. Electricity is very unreliable in the country; most homes only have electricity a few hours per day. When buildings on one side of the street are blacked out, the other side gets electricity. When this situation occurs, there is a mad rush of children who run to their friends’ apartments on the other side. Internet is only available to the elite in North Korea. Even cellphones are extremely rare. Only people who are trusted by the government can buy a cell phone, but they must pay a registration fee of $825.