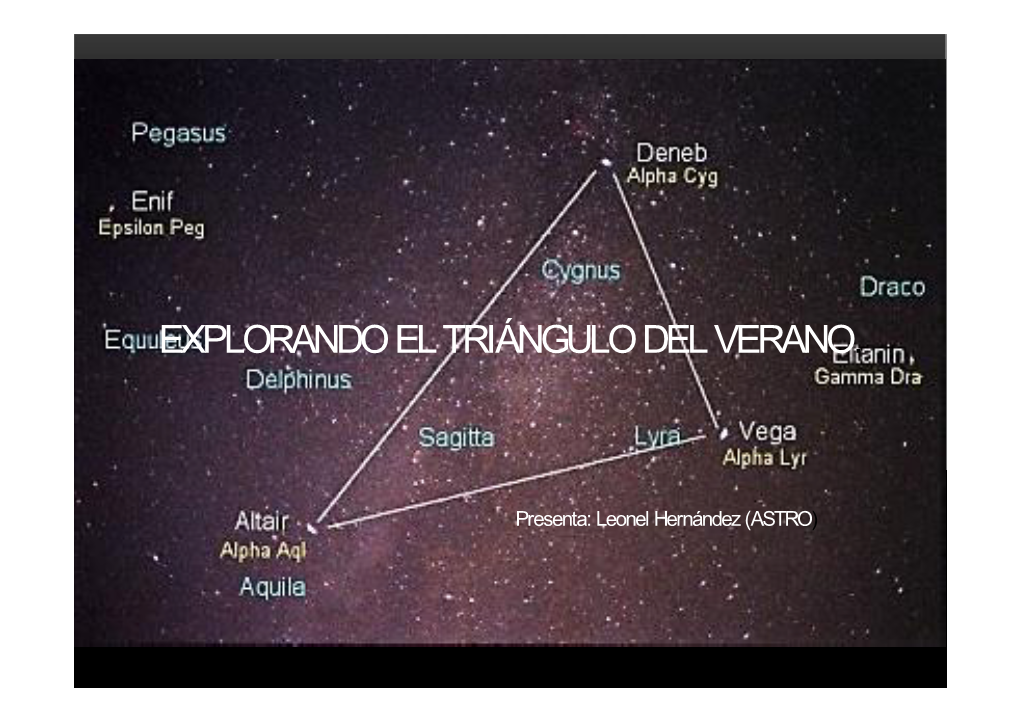

Explorando El Triángulo Del Verano

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Messier Objects

Messier Objects From the Stocker Astroscience Center at Florida International University Miami Florida The Messier Project Main contributors: • Daniel Puentes • Steven Revesz • Bobby Martinez Charles Messier • Gabriel Salazar • Riya Gandhi • Dr. James Webb – Director, Stocker Astroscience center • All images reduced and combined using MIRA image processing software. (Mirametrics) What are Messier Objects? • Messier objects are a list of astronomical sources compiled by Charles Messier, an 18th and early 19th century astronomer. He created a list of distracting objects to avoid while comet hunting. This list now contains over 110 objects, many of which are the most famous astronomical bodies known. The list contains planetary nebula, star clusters, and other galaxies. - Bobby Martinez The Telescope The telescope used to take these images is an Astronomical Consultants and Equipment (ACE) 24- inch (0.61-meter) Ritchey-Chretien reflecting telescope. It has a focal ratio of F6.2 and is supported on a structure independent of the building that houses it. It is equipped with a Finger Lakes 1kx1k CCD camera cooled to -30o C at the Cassegrain focus. It is equipped with dual filter wheels, the first containing UBVRI scientific filters and the second RGBL color filters. Messier 1 Found 6,500 light years away in the constellation of Taurus, the Crab Nebula (known as M1) is a supernova remnant. The original supernova that formed the crab nebula was observed by Chinese, Japanese and Arab astronomers in 1054 AD as an incredibly bright “Guest star” which was visible for over twenty-two months. The supernova that produced the Crab Nebula is thought to have been an evolved star roughly ten times more massive than the Sun. -

Guide Du Ciel Profond

Guide du ciel profond Olivier PETIT 8 mai 2004 2 Introduction hjjdfhgf ghjfghfd fg hdfjgdf gfdhfdk dfkgfd fghfkg fdkg fhdkg fkg kfghfhk Table des mati`eres I Objets par constellation 21 1 Androm`ede (And) Andromeda 23 1.1 Messier 31 (La grande Galaxie d'Androm`ede) . 25 1.2 Messier 32 . 27 1.3 Messier 110 . 29 1.4 NGC 404 . 31 1.5 NGC 752 . 33 1.6 NGC 891 . 35 1.7 NGC 7640 . 37 1.8 NGC 7662 (La boule de neige bleue) . 39 2 La Machine pneumatique (Ant) Antlia 41 2.1 NGC 2997 . 43 3 le Verseau (Aqr) Aquarius 45 3.1 Messier 2 . 47 3.2 Messier 72 . 49 3.3 Messier 73 . 51 3.4 NGC 7009 (La n¶ebuleuse Saturne) . 53 3.5 NGC 7293 (La n¶ebuleuse de l'h¶elice) . 56 3.6 NGC 7492 . 58 3.7 NGC 7606 . 60 3.8 Cederblad 211 (N¶ebuleuse de R Aquarii) . 62 4 l'Aigle (Aql) Aquila 63 4.1 NGC 6709 . 65 4.2 NGC 6741 . 67 4.3 NGC 6751 (La n¶ebuleuse de l’œil flou) . 69 4.4 NGC 6760 . 71 4.5 NGC 6781 (Le nid de l'Aigle ) . 73 TABLE DES MATIERES` 5 4.6 NGC 6790 . 75 4.7 NGC 6804 . 77 4.8 Barnard 142-143 (La tani`ere noire) . 79 5 le B¶elier (Ari) Aries 81 5.1 NGC 772 . 83 6 le Cocher (Aur) Auriga 85 6.1 Messier 36 . 87 6.2 Messier 37 . 89 6.3 Messier 38 . -

A Basic Requirement for Studying the Heavens Is Determining Where In

Abasic requirement for studying the heavens is determining where in the sky things are. To specify sky positions, astronomers have developed several coordinate systems. Each uses a coordinate grid projected on to the celestial sphere, in analogy to the geographic coordinate system used on the surface of the Earth. The coordinate systems differ only in their choice of the fundamental plane, which divides the sky into two equal hemispheres along a great circle (the fundamental plane of the geographic system is the Earth's equator) . Each coordinate system is named for its choice of fundamental plane. The equatorial coordinate system is probably the most widely used celestial coordinate system. It is also the one most closely related to the geographic coordinate system, because they use the same fun damental plane and the same poles. The projection of the Earth's equator onto the celestial sphere is called the celestial equator. Similarly, projecting the geographic poles on to the celest ial sphere defines the north and south celestial poles. However, there is an important difference between the equatorial and geographic coordinate systems: the geographic system is fixed to the Earth; it rotates as the Earth does . The equatorial system is fixed to the stars, so it appears to rotate across the sky with the stars, but of course it's really the Earth rotating under the fixed sky. The latitudinal (latitude-like) angle of the equatorial system is called declination (Dec for short) . It measures the angle of an object above or below the celestial equator. The longitud inal angle is called the right ascension (RA for short). -

Governs the Making of Photocopies Or Other Reproductions of Copyrighted Materials

Warning Concerning Copyright Restrictions The Copyright Law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted materials. Under certain conditions specified in the law, libraries and archives are authorized to furnish a photocopy or other reproduction. One of these specified conditions is that the photocopy or reproduction is not to be used for any purpose other than private study, scholarship, or research. If electronic transmission of reserve material is used for purposes in excess of what constitutes "fair use," that user may be liable for copyright infringement. University of Nevada, Reno A Photometric Survey and Analysis of the M29 and M52 Open Star Clusters at the University of Nevada, Reno A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Science in Physics by Matthew N. Tooth Dr. Melodi Rodrigue, Ph.D., Thesis Advisor December, 2012 UNIVERSITY OF NEVADA THE HONORS PROGRAM RENO We recommend that the thesis prepared under our supervision by Matthew N. Tooth entitled A Photometric Survey and Analysis of the M29 and M52 Open Star Clusters at the University of Nevada, Reno be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Science, Physics ______________________________________________ Melodi Rodrigue, Ph.D., Thesis Advisor ______________________________________________ David Bennum, Ph.D., Thesis Reader ______________________________________________ Tamara Valentine, Ph.D., Director, Honors Program December, 2012 ! i! Abstract One of the many tools at an astronomer’s disposal is photometry. By measuring the magnitudes of stars in star clusters in various wavelength filters we can obtain data that can provide important pieces of information about groups of stars. -

Patrick Moore's Practical Astronomy Series

Patrick Moore’s Practical Astronomy Series Other Titles in this Series Navigating the Night Sky Astronomy of the Milky Way How to Identify the Stars and The Observer’s Guide to the Constellations Southern/Northern Sky Parts 1 and 2 Guilherme de Almeida hardcover set Observing and Measuring Visual Mike Inglis Double Stars Astronomy of the Milky Way Bob Argyle (Ed.) Part 1: Observer’s Guide to the Observing Meteors, Comets, Supernovae Northern Sky and other transient Phenomena Mike Inglis Neil Bone Astronomy of the Milky Way Human Vision and The Night Sky Part 2: Observer’s Guide to the How to Improve Your Observing Skills Southern Sky Michael P. Borgia Mike Inglis How to Photograph the Moon and Planets Observing Comets with Your Digital Camera Nick James and Gerald North Tony Buick Telescopes and Techniques Practical Astrophotography An Introduction to Practical Astronomy Jeffrey R. Charles Chris Kitchin Pattern Asterisms Seeing Stars A New Way to Chart the Stars The Night Sky Through Small Telescopes John Chiravalle Chris Kitchin and Robert W. Forrest Deep Sky Observing Photo-guide to the Constellations The Astronomical Tourist A Self-Teaching Guide to Finding Your Steve R. Coe Way Around the Heavens Chris Kitchin Visual Astronomy in the Suburbs A Guide to Spectacular Viewing Solar Observing Techniques Antony Cooke Chris Kitchin Visual Astronomy Under Dark Skies How to Observe the Sun Safely A New Approach to Observing Deep Space Lee Macdonald Antony Cooke The Sun in Eclipse Real Astronomy with Small Telescopes Sir Patrick Moore and Michael Maunder Step-by-Step Activities for Discovery Transit Michael K. -

The Messier Catalog

The Messier Catalog Messier 1 Messier 2 Messier 3 Messier 4 Messier 5 Crab Nebula globular cluster globular cluster globular cluster globular cluster Messier 6 Messier 7 Messier 8 Messier 9 Messier 10 open cluster open cluster Lagoon Nebula globular cluster globular cluster Butterfly Cluster Ptolemy's Cluster Messier 11 Messier 12 Messier 13 Messier 14 Messier 15 Wild Duck Cluster globular cluster Hercules glob luster globular cluster globular cluster Messier 16 Messier 17 Messier 18 Messier 19 Messier 20 Eagle Nebula The Omega, Swan, open cluster globular cluster Trifid Nebula or Horseshoe Nebula Messier 21 Messier 22 Messier 23 Messier 24 Messier 25 open cluster globular cluster open cluster Milky Way Patch open cluster Messier 26 Messier 27 Messier 28 Messier 29 Messier 30 open cluster Dumbbell Nebula globular cluster open cluster globular cluster Messier 31 Messier 32 Messier 33 Messier 34 Messier 35 Andromeda dwarf Andromeda Galaxy Triangulum Galaxy open cluster open cluster elliptical galaxy Messier 36 Messier 37 Messier 38 Messier 39 Messier 40 open cluster open cluster open cluster open cluster double star Winecke 4 Messier 41 Messier 42/43 Messier 44 Messier 45 Messier 46 open cluster Orion Nebula Praesepe Pleiades open cluster Beehive Cluster Suburu Messier 47 Messier 48 Messier 49 Messier 50 Messier 51 open cluster open cluster elliptical galaxy open cluster Whirlpool Galaxy Messier 52 Messier 53 Messier 54 Messier 55 Messier 56 open cluster globular cluster globular cluster globular cluster globular cluster Messier 57 Messier -

FY13 High-Level Deliverables

National Optical Astronomy Observatory Fiscal Year Annual Report for FY 2013 (1 October 2012 – 30 September 2013) Submitted to the National Science Foundation Pursuant to Cooperative Support Agreement No. AST-0950945 13 December 2013 Revised 18 September 2014 Contents NOAO MISSION PROFILE .................................................................................................... 1 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................................ 2 2 NOAO ACCOMPLISHMENTS ....................................................................................... 4 2.1 Achievements ..................................................................................................... 4 2.2 Status of Vision and Goals ................................................................................. 5 2.2.1 Status of FY13 High-Level Deliverables ............................................ 5 2.2.2 FY13 Planned vs. Actual Spending and Revenues .............................. 8 2.3 Challenges and Their Impacts ............................................................................ 9 3 SCIENTIFIC ACTIVITIES AND FINDINGS .............................................................. 11 3.1 Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory ....................................................... 11 3.2 Kitt Peak National Observatory ....................................................................... 14 3.3 Gemini Observatory ........................................................................................ -

Astronomical Coordinate Systems

Appendix 1 Astronomical Coordinate Systems A basic requirement for studying the heavens is being able to determine where in the sky things are located. To specify sky positions, astronomers have developed several coordinate systems. Each sys- tem uses a coordinate grid projected on the celestial sphere, which is similar to the geographic coor- dinate system used on the surface of the Earth. The coordinate systems differ only in their choice of the fundamental plane, which divides the sky into two equal hemispheres along a great circle (the fundamental plane of the geographic system is the Earth’s equator). Each coordinate system is named for its choice of fundamental plane. The Equatorial Coordinate System The equatorial coordinate system is probably the most widely used celestial coordinate system. It is also the most closely related to the geographic coordinate system because they use the same funda- mental plane and poles. The projection of the Earth’s equator onto the celestial sphere is called the celestial equator. Similarly, projecting the geographic poles onto the celestial sphere defines the north and south celestial poles. However, there is an important difference between the equatorial and geographic coordinate sys- tems: the geographic system is fixed to the Earth and rotates as the Earth does. The Equatorial system is fixed to the stars, so it appears to rotate across the sky with the stars, but it’s really the Earth rotating under the fixed sky. The latitudinal (latitude-like) angle of the equatorial system is called declination (Dec. for short). It measures the angle of an object above or below the celestial equator. -

Deep Sky Explorer Atlas

Deep Sky Explorer Atlas Reference manual Star charts for the southern skies Compiled by Auke Slotegraaf and distributed under an Attribution-Noncommercial 3.0 Creative Commons license. Version 0.20, January 2009 Deep Sky Explorer Atlas Introduction Deep Sky Explorer Atlas Reference manual The Deep Sky Explorer’s Atlas consists of 30 wide-field star charts, from the south pole to declination +45°, showing all stars down to 8th magnitude and over 1 000 deep sky objects. The design philosophy of the Atlas was to depict the night sky as it is seen, without the clutter of constellation boundary lines, RA/Dec fiducial markings, or other labels. However, constellations are identified by their standard three-letter abbreviations as a minimal aid to orientation. Those wishing to use charts showing an array of invisible lines, numbers and letters will find elsewhere a wide selection of star charts; these include the Herald-Bobroff Astroatlas, the Cambridge Star Atlas, Uranometria 2000.0, and the Millenium Star Atlas. The Deep Sky Explorer Atlas is very much for the explorer. Special mention should be made of the excellent charts by Toshimi Taki and Andrew L. Johnson. Both are free to download and make ideal complements to this Atlas. Andrew Johnson’s wide-field charts include constellation figures and stellar designations and are highly recommended for learning the constellations. They can be downloaded from http://www.cloudynights.com/item.php?item_id=1052 Toshimi Taki has produced the excellent “Taki’s 8.5 Magnitude Star Atlas” which is a serious competitor for the commercial Uranometria atlas. His atlas has 149 charts and is available from http://www.asahi-net.or.jp/~zs3t-tk/atlas_85/atlas_85.htm Suggestions on how to use the Atlas Because the Atlas is distributed in digital format, its pages can be printed on a standard laser printer as needed. -

Charles Messier (1730-1817) Was an Observational Astronomer Working

Charles Messier (1730-1817) was an observational Catalogue (NGC) which was being compiled at the same astronomer working from Paris in the eighteenth century. time as Messier's observations but using much larger tele He discovered between 15 and 21 comets and observed scopes, probably explains its modern popularity. It is a many more. During his observations he encountered neb challenging but achievable task for most amateur astron ulous objects that were not comets. Some of these objects omers to observe all the Messier objects. At «star parties" were his own discoveries, while others had been known and within astronomy clubs, going for the maximum before. In 1774 he published a list of 45 of these nebulous number of Messier objects observed is a popular competi objects. His purpose in publishing the list was so that tion. Indeed at some times of the year it is just about poss other comet-hunters should not confuse the nebulae with ible to observe most of them in a single night. comets. Over the following decades he published supple Messier observed from Paris and therefore the most ments which increased the number of objects in his cata southerly object in his list is M7 in Scorpius with a decli logue to 103 though objects M101 and M102 were in fact nation of -35°. He also missed several objects from his list the same. Later other astronomers added a replacement such as h and X Per and the Hyades which most observers for M102 and objects 104 to 110. It is now thought proba would feel should have been included. -

September 2013

NEWBURY ASTRONOMICAL SOCIETY MONTHLY MAGAZINE - SEPTEMBER 2013 WELCOME TO THE 2013-2014 ASTRONOMY SESSION After the summer recess we are back and into the 2013 – Attendance at the monthly Beginner’s meetings has also 2014 astronomical observing session that runs from been at an all-time high with an average attendance of 60 September 2013 through to June 2014. The Newbury to 70. For the time being the monthly meetings will Astronomical Society had its most successful year in the continue to be held at St. Mary’s Church Hall, Greenham. last session. The membership of the society is now at an Details can be found on the Beginners website at the all-time high with 100 paid up members. The numbers address shown at the bottom of this page. have grown so much over the last couple of sessions it has Last session three additional special practical events, become necessary to move the main speaker meeting to a known as Telescope Workshop Evenings were held at the larger venue. The move to the new venue will take place th Ashford Hill Village Hall. These events were well attended starting with the first meeting on 6 September. so it is intended to hold a number of similar events this The new venue not only offers more space for the session. The themes for the last session workshops were: increased membership but also has its own parking area Assembling your new telescope, Setting up your telescope and the advantage of a dark site for observing when it is for observing and Imaging using a webcam mounted to a clear. -

Édition Août 2014 « DU SAVOIR AU VÉCU »

Édition Août 2014 « DU SAVOIR AU VÉCU » SOMMAIRE Le mot de l’éditeur ................................................................................................ 4 Événements, nouvelles et anecdotes ................................................................... 5 11 juillet à St-Pierre, un vendredi occupé ................................................................... 5 Un 24 juillet à St-Pierre… ............................................................................................. 5 De nouveaux membres à St-Pierre .............................................................................. 6 SMI 9 août Massif du Sud ............................................................................................ 6 Question d’astronomie .......................................................................................... 7 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko .................................................................................... 7 La sonde Rosetta, des précisions de Pierre ................................................................. 8 Gamma du Cygne......................................................................................................... 8 La région du Cygne ...................................................................................................... 9 M 57 par les pros ....................................................................................................... 10 UGC 10822 ................................................................................................................