Arxiv:0706.1988V3 [Physics.Ed-Ph] 15 Jun 2016 M ~R + M ~R R~ = 1 1 2 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Building Blocks That Fall from the Sky

Building blocks that fall from the sky How did life on Earth begin? Scientists from the “Heidelberg Initiative for the Origin of Life” have set about answering this truly existential question. Indeed, they are going one step further and examining the conditions under which life can emerge. The initiative was founded by Thomas Henning, Director at the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy in Heidelberg, and brings together researchers from chemistry, physics and the geological and biological sciences. 18 MaxPlanckResearch 3 | 18 FOCUS_The Origin of Life TEXT THOMAS BUEHRKE he great questions of our exis- However, recent developments are The initiative was triggered by the dis- tence are the ones that fasci- forcing researchers to break down this covery of an ever greater number of nate us the most: how did the specialization and combine different rocky planets orbiting around stars oth- universe evolve, and how did disciplines. “That’s what we’re trying er than the Sun. “We now know that Earth form and life begin? to do with the Heidelberg Initiative terrestrial planets of this kind are more DoesT life exist anywhere else, or are we for the Origins of Life, which was commonplace than the Jupiter-like gas alone in the vastness of space? By ap- founded three years ago,” says Thom- giants we identified initially,” says Hen- proaching these puzzles from various as Henning. HIFOL, as the initiative’s ning. Accordingly, our Milky Way alone angles, scientists can answer different as- name is abbreviated, not only incor- is home to billions of rocky planets, pects of this question. -

Exploring Exoplanet Populations with NASA's Kepler Mission

SPECIAL FEATURE: PERSPECTIVE PERSPECTIVE SPECIAL FEATURE: Exploring exoplanet populations with NASA’s Kepler Mission Natalie M. Batalha1 National Aeronautics and Space Administration Ames Research Center, Moffett Field, 94035 CA Edited by Adam S. Burrows, Princeton University, Princeton, NJ, and accepted by the Editorial Board June 3, 2014 (received for review January 15, 2014) The Kepler Mission is exploring the diversity of planets and planetary systems. Its legacy will be a catalog of discoveries sufficient for computing planet occurrence rates as a function of size, orbital period, star type, and insolation flux.The mission has made significant progress toward achieving that goal. Over 3,500 transiting exoplanets have been identified from the analysis of the first 3 y of data, 100 planets of which are in the habitable zone. The catalog has a high reliability rate (85–90% averaged over the period/radius plane), which is improving as follow-up observations continue. Dynamical (e.g., velocimetry and transit timing) and statistical methods have confirmed and characterized hundreds of planets over a large range of sizes and compositions for both single- and multiple-star systems. Population studies suggest that planets abound in our galaxy and that small planets are particularly frequent. Here, I report on the progress Kepler has made measuring the prevalence of exoplanets orbiting within one astronomical unit of their host stars in support of the National Aeronautics and Space Admin- istration’s long-term goal of finding habitable environments beyond the solar system. planet detection | transit photometry Searching for evidence of life beyond Earth is the Sun would produce an 84-ppm signal Translating Kepler’s discovery catalog into one of the primary goals of science agencies lasting ∼13 h. -

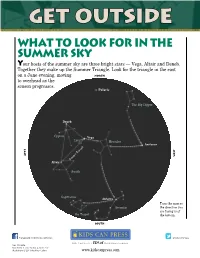

Get Outside What to Look for in the Summer Sky Your Hosts of the Summer Sky Are Three Bright Stars — Vega, Altair and Deneb

Get Outside What to Look for in the Summer Sky Your hosts of the summer sky are three bright stars — Vega, Altair and Deneb. Together they make up the Summer Triangle. Look for the triangle in the east on a June evening, moving NORTH to overhead as the season progresses. Polaris The Big Dipper Deneb Cygnus Vega Lyra Hercules Arcturus EaST West Summer Triangle Altair Aquila Sagittarius Antares Turn the map so Scorpius the direction you are facing is at the Teapot the bottom. south facebook.com/KidsCanBooks @KidsCanPress GET OUTSIDE Text © 2013 Jane Drake & Ann Love Illustrations © 2013 Heather Collins www.kidscanpress.com Get Outside Vega The Keystone The brightest star in the Between Vega and Arcturus, Summer Triangle, Vega is look for four stars in a wedge or The summer bluish white. It is in the keystone shape. This is the body solstice constellation Lyra, the Harp. of Hercules, the Strongman. His feet are to the north and Every day from late Altair his arms to the south, making December to June, the The second-brightest star in his figure kneel Sun rises and sets a little the triangle, Altair is white. upside down farther north along the Altair is in the constellation in the sky. horizon. But about June Aquila, the Eagle. 21, the Sun seems to stop Keystone moving north. It rises in Deneb the northeast and sets in The dimmest star of the the northwest, seemingly Summer Triangle, Deneb would in the same spots for be the brightest if it were not so Hercules several days. -

![Arxiv:2012.09981V1 [Astro-Ph.SR] 17 Dec 2020 2 O](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3257/arxiv-2012-09981v1-astro-ph-sr-17-dec-2020-2-o-73257.webp)

Arxiv:2012.09981V1 [Astro-Ph.SR] 17 Dec 2020 2 O

Contrib. Astron. Obs. Skalnat´ePleso XX, 1 { 20, (2020) DOI: to be assigned later Flare stars in nearby Galactic open clusters based on TESS data Olga Maryeva1;2, Kamil Bicz3, Caiyun Xia4, Martina Baratella5, Patrik Cechvalaˇ 6 and Krisztian Vida7 1 Astronomical Institute of the Czech Academy of Sciences 251 65 Ondˇrejov,The Czech Republic(E-mail: [email protected]) 2 Lomonosov Moscow State University, Sternberg Astronomical Institute, Universitetsky pr. 13, 119234, Moscow, Russia 3 Astronomical Institute, University of Wroc law, Kopernika 11, 51-622 Wroc law, Poland 4 Department of Theoretical Physics and Astrophysics, Faculty of Science, Masaryk University, Kotl´aˇrsk´a2, 611 37 Brno, Czech Republic 5 Dipartimento di Fisica e Astronomia Galileo Galilei, Vicolo Osservatorio 3, 35122, Padova, Italy, (E-mail: [email protected]) 6 Department of Astronomy, Physics of the Earth and Meteorology, Faculty of Mathematics, Physics and Informatics, Comenius University in Bratislava, Mlynsk´adolina F-2, 842 48 Bratislava, Slovakia 7 Konkoly Observatory, Research Centre for Astronomy and Earth Sciences, H-1121 Budapest, Konkoly Thege Mikl´os´ut15-17, Hungary Received: September ??, 2020; Accepted: ????????? ??, 2020 Abstract. The study is devoted to search for flare stars among confirmed members of Galactic open clusters using high-cadence photometry from TESS mission. We analyzed 957 high-cadence light curves of members from 136 open clusters. As a result, 56 flare stars were found, among them 8 hot B-A type ob- jects. Of all flares, 63 % were detected in sample of cool stars (Teff < 5000 K), and 29 % { in stars of spectral type G, while 23 % in K-type stars and ap- proximately 34% of all detected flares are in M-type stars. -

Messier Objects

Messier Objects From the Stocker Astroscience Center at Florida International University Miami Florida The Messier Project Main contributors: • Daniel Puentes • Steven Revesz • Bobby Martinez Charles Messier • Gabriel Salazar • Riya Gandhi • Dr. James Webb – Director, Stocker Astroscience center • All images reduced and combined using MIRA image processing software. (Mirametrics) What are Messier Objects? • Messier objects are a list of astronomical sources compiled by Charles Messier, an 18th and early 19th century astronomer. He created a list of distracting objects to avoid while comet hunting. This list now contains over 110 objects, many of which are the most famous astronomical bodies known. The list contains planetary nebula, star clusters, and other galaxies. - Bobby Martinez The Telescope The telescope used to take these images is an Astronomical Consultants and Equipment (ACE) 24- inch (0.61-meter) Ritchey-Chretien reflecting telescope. It has a focal ratio of F6.2 and is supported on a structure independent of the building that houses it. It is equipped with a Finger Lakes 1kx1k CCD camera cooled to -30o C at the Cassegrain focus. It is equipped with dual filter wheels, the first containing UBVRI scientific filters and the second RGBL color filters. Messier 1 Found 6,500 light years away in the constellation of Taurus, the Crab Nebula (known as M1) is a supernova remnant. The original supernova that formed the crab nebula was observed by Chinese, Japanese and Arab astronomers in 1054 AD as an incredibly bright “Guest star” which was visible for over twenty-two months. The supernova that produced the Crab Nebula is thought to have been an evolved star roughly ten times more massive than the Sun. -

Introduction to Astronomy from Darkness to Blazing Glory

Introduction to Astronomy From Darkness to Blazing Glory Published by JAS Educational Publications Copyright Pending 2010 JAS Educational Publications All rights reserved. Including the right of reproduction in whole or in part in any form. Second Edition Author: Jeffrey Wright Scott Photographs and Diagrams: Credit NASA, Jet Propulsion Laboratory, USGS, NOAA, Aames Research Center JAS Educational Publications 2601 Oakdale Road, H2 P.O. Box 197 Modesto California 95355 1-888-586-6252 Website: http://.Introastro.com Printing by Minuteman Press, Berkley, California ISBN 978-0-9827200-0-4 1 Introduction to Astronomy From Darkness to Blazing Glory The moon Titan is in the forefront with the moon Tethys behind it. These are two of many of Saturn’s moons Credit: Cassini Imaging Team, ISS, JPL, ESA, NASA 2 Introduction to Astronomy Contents in Brief Chapter 1: Astronomy Basics: Pages 1 – 6 Workbook Pages 1 - 2 Chapter 2: Time: Pages 7 - 10 Workbook Pages 3 - 4 Chapter 3: Solar System Overview: Pages 11 - 14 Workbook Pages 5 - 8 Chapter 4: Our Sun: Pages 15 - 20 Workbook Pages 9 - 16 Chapter 5: The Terrestrial Planets: Page 21 - 39 Workbook Pages 17 - 36 Mercury: Pages 22 - 23 Venus: Pages 24 - 25 Earth: Pages 25 - 34 Mars: Pages 34 - 39 Chapter 6: Outer, Dwarf and Exoplanets Pages: 41-54 Workbook Pages 37 - 48 Jupiter: Pages 41 - 42 Saturn: Pages 42 - 44 Uranus: Pages 44 - 45 Neptune: Pages 45 - 46 Dwarf Planets, Plutoids and Exoplanets: Pages 47 -54 3 Chapter 7: The Moons: Pages: 55 - 66 Workbook Pages 49 - 56 Chapter 8: Rocks and Ice: -

![Arxiv:2012.15102V2 [Hep-Ph] 13 May 2021 T > Tc](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5512/arxiv-2012-15102v2-hep-ph-13-may-2021-t-tc-185512.webp)

Arxiv:2012.15102V2 [Hep-Ph] 13 May 2021 T > Tc

Confinement of Fermions in Tachyon Matter at Finite Temperature Adamu Issifu,1, ∗ Julio C.M. Rocha,1, y and Francisco A. Brito1, 2, z 1Departamento de F´ısica, Universidade Federal da Para´ıba, Caixa Postal 5008, 58051-970 Jo~aoPessoa, Para´ıba, Brazil 2Departamento de F´ısica, Universidade Federal de Campina Grande Caixa Postal 10071, 58429-900 Campina Grande, Para´ıba, Brazil We study a phenomenological model that mimics the characteristics of QCD theory at finite temperature. The model involves fermions coupled with a modified Abelian gauge field in a tachyon matter. It reproduces some important QCD features such as, confinement, deconfinement, chiral symmetry and quark-gluon-plasma (QGP) phase transitions. The study may shed light on both light and heavy quark potentials and their string tensions. Flux-tube and Cornell potentials are developed depending on the regime under consideration. Other confining properties such as scalar glueball mass, gluon mass, glueball-meson mixing states, gluon and chiral condensates are exploited as well. The study is focused on two possible regimes, the ultraviolet (UV) and the infrared (IR) regimes. I. INTRODUCTION Confinement of heavy quark states QQ¯ is an important subject in both theoretical and experimental study of high temperature QCD matter and quark-gluon-plasma phase (QGP) [1]. The production of heavy quarkonia such as the fundamental state ofcc ¯ in the Relativistic Heavy Iron Collider (RHIC) [2] and the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) [3] provides basics for the study of QGP. Lattice QCD simulations of quarkonium at finite temperature indicates that J= may persists even at T = 1:5Tc [4] i.e. -

Imagining Outer Space Also by Alexander C

Imagining Outer Space Also by Alexander C. T. Geppert FLEETING CITIES Imperial Expositions in Fin-de-Siècle Europe Co-Edited EUROPEAN EGO-HISTORIES Historiography and the Self, 1970–2000 ORTE DES OKKULTEN ESPOSIZIONI IN EUROPA TRA OTTO E NOVECENTO Spazi, organizzazione, rappresentazioni ORTSGESPRÄCHE Raum und Kommunikation im 19. und 20. Jahrhundert NEW DANGEROUS LIAISONS Discourses on Europe and Love in the Twentieth Century WUNDER Poetik und Politik des Staunens im 20. Jahrhundert Imagining Outer Space European Astroculture in the Twentieth Century Edited by Alexander C. T. Geppert Emmy Noether Research Group Director Freie Universität Berlin Editorial matter, selection and introduction © Alexander C. T. Geppert 2012 Chapter 6 (by Michael J. Neufeld) © the Smithsonian Institution 2012 All remaining chapters © their respective authors 2012 All rights reserved. No reproduction, copy or transmission of this publication may be made without written permission. No portion of this publication may be reproduced, copied or transmitted save with written permission or in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, or under the terms of any licence permitting limited copying issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency, Saffron House, 6–10 Kirby Street, London EC1N 8TS. Any person who does any unauthorized act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages. The authors have asserted their rights to be identified as the authors of this work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. First published 2012 by PALGRAVE MACMILLAN Palgrave Macmillan in the UK is an imprint of Macmillan Publishers Limited, registered in England, company number 785998, of Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire RG21 6XS. -

Guide Du Ciel Profond

Guide du ciel profond Olivier PETIT 8 mai 2004 2 Introduction hjjdfhgf ghjfghfd fg hdfjgdf gfdhfdk dfkgfd fghfkg fdkg fhdkg fkg kfghfhk Table des mati`eres I Objets par constellation 21 1 Androm`ede (And) Andromeda 23 1.1 Messier 31 (La grande Galaxie d'Androm`ede) . 25 1.2 Messier 32 . 27 1.3 Messier 110 . 29 1.4 NGC 404 . 31 1.5 NGC 752 . 33 1.6 NGC 891 . 35 1.7 NGC 7640 . 37 1.8 NGC 7662 (La boule de neige bleue) . 39 2 La Machine pneumatique (Ant) Antlia 41 2.1 NGC 2997 . 43 3 le Verseau (Aqr) Aquarius 45 3.1 Messier 2 . 47 3.2 Messier 72 . 49 3.3 Messier 73 . 51 3.4 NGC 7009 (La n¶ebuleuse Saturne) . 53 3.5 NGC 7293 (La n¶ebuleuse de l'h¶elice) . 56 3.6 NGC 7492 . 58 3.7 NGC 7606 . 60 3.8 Cederblad 211 (N¶ebuleuse de R Aquarii) . 62 4 l'Aigle (Aql) Aquila 63 4.1 NGC 6709 . 65 4.2 NGC 6741 . 67 4.3 NGC 6751 (La n¶ebuleuse de l’œil flou) . 69 4.4 NGC 6760 . 71 4.5 NGC 6781 (Le nid de l'Aigle ) . 73 TABLE DES MATIERES` 5 4.6 NGC 6790 . 75 4.7 NGC 6804 . 77 4.8 Barnard 142-143 (La tani`ere noire) . 79 5 le B¶elier (Ari) Aries 81 5.1 NGC 772 . 83 6 le Cocher (Aur) Auriga 85 6.1 Messier 36 . 87 6.2 Messier 37 . 89 6.3 Messier 38 . -

Hints Into Kepler's Method

Stefano Gattei [email protected] Hints into Kepler’s method ABSTRACT The Italian Academy, Columbia University February 4, 2009 Some of Johannes Kepler’s works seem very different in character. His youthful Mysterium cosmographicum (1596) argues for heliocentrism on the basis of metaphysical, astronomical, astrological, numerological, and architectonic principles. By contrast, Astronomia nova (1609) is far more tightly argued on the basis of only a few dynamical principles. In the eyes of many, such a contrast embodies a transition from Renaissance to early modern science. However, Kepler did not subsequently abandon the broader approach of his early works: similar metaphysical arguments reappeared in Harmonices mundi libri V (1619), and he reissued the Mysterium cosmographicum in a second edition in 1621, in which he qualified only some of his youthful arguments. I claim that the conceptual and stylistic features of the Astronomia nova – as well as of other “minor” works, such as Strena seu De nive sexangula (1611) or Nova stereometria doliorum vinariorum (1615) – are intimately related and were purposely chosen because of the response he knew to expect from the astronomical community to the revolutionary changes in astronomy he was proposing. Far from being a stream-of-consciousness or merely rhetorical kind of narrative, as many scholars have argued, Kepler’s expository method was carefully calculated both to convince his readers and to engage them in a critical discussion in the joint effort to know God’s design. By abandoning the perspective of the inductivist philosophy of science, which is forced by its own standards to portray Kepler as a “sleepwalker,” I argue that the key lies in the examination of Kepler’s method: whether considering the functioning and structure of the heavens or the tiny geometry of the little snowflakes, he never hesitated to discuss his own intellectual journey, offering a rational reconstruction of the series of false starts, blind alleys, and failures he encountered. -

Aspects of Spatially Homogeneous and Isotropic Cosmology

Faculty of Technology and Science Department of Physics and Electrical Engineering Mikael Isaksson Aspects of Spatially Homogeneous and Isotropic Cosmology Degree Project of 15 credit points Physics Program Date/Term: 02-04-11 Supervisor: Prof. Claes Uggla Examiner: Prof. Jürgen Fuchs Karlstads universitet 651 88 Karlstad Tfn 054-700 10 00 Fax 054-700 14 60 [email protected] www.kau.se Abstract In this thesis, after a general introduction, we first review some differential geom- etry to provide the mathematical background needed to derive the key equations in cosmology. Then we consider the Robertson-Walker geometry and its relation- ship to cosmography, i.e., how one makes measurements in cosmology. We finally connect the Robertson-Walker geometry to Einstein's field equation to obtain so- called cosmological Friedmann-Lema^ıtre models. These models are subsequently studied by means of potential diagrams. 1 CONTENTS CONTENTS Contents 1 Introduction 3 2 Differential geometry prerequisites 8 3 Cosmography 13 3.1 Robertson-Walker geometry . 13 3.2 Concepts and measurements in cosmography . 18 4 Friedmann-Lema^ıtre dynamics 30 5 Bibliography 42 2 1 INTRODUCTION 1 Introduction Cosmology comes from the Greek word kosmos, `universe' and logia, `study', and is the study of the large-scale structure, origin, and evolution of the universe, that is, of the universe taken as a whole [1]. Even though the word cosmology is relatively recent (first used in 1730 in Christian Wolff's Cosmologia Generalis), the study of the universe has a long history involving science, philosophy, eso- tericism, and religion. Cosmologies in their earliest form were concerned with, what is now known as celestial mechanics (the study of the heavens). -

The Feeble Giant. Discovery of a Large and Diffuse Milky Way Dwarf Galaxy in the Constellation of Crater

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Apollo MNRAS 459, 2370–2378 (2016) doi:10.1093/mnras/stw733 Advance Access publication 2016 April 13 The feeble giant. Discovery of a large and diffuse Milky Way dwarf galaxy in the constellation of Crater G. Torrealba,‹ S. E. Koposov, V. Belokurov and M. Irwin Institute of Astronomy, Madingley Rd, Cambridge CB3 0HA, UK Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/mnras/article-abstract/459/3/2370/2595158 by University of Cambridge user on 24 July 2019 Accepted 2016 March 24. Received 2016 March 24; in original form 2016 January 26 ABSTRACT We announce the discovery of the Crater 2 dwarf galaxy, identified in imaging data of the VLT Survey Telescope ATLAS survey. Given its half-light radius of ∼1100 pc, Crater 2 is the fourth largest satellite of the Milky Way, surpassed only by the Large Magellanic Cloud, Small Magellanic Cloud and the Sgr dwarf. With a total luminosity of MV ≈−8, this galaxy is also one of the lowest surface brightness dwarfs. Falling under the nominal detection boundary of 30 mag arcsec−2, it compares in nebulosity to the recently discovered Tuc 2 and Tuc IV and UMa II. Crater 2 is located ∼120 kpc from the Sun and appears to be aligned in 3D with the enigmatic globular cluster Crater, the pair of ultrafaint dwarfs Leo IV and Leo V and the classical dwarf Leo II. We argue that such arrangement is probably not accidental and, in fact, can be viewed as the evidence for the accretion of the Crater-Leo group.