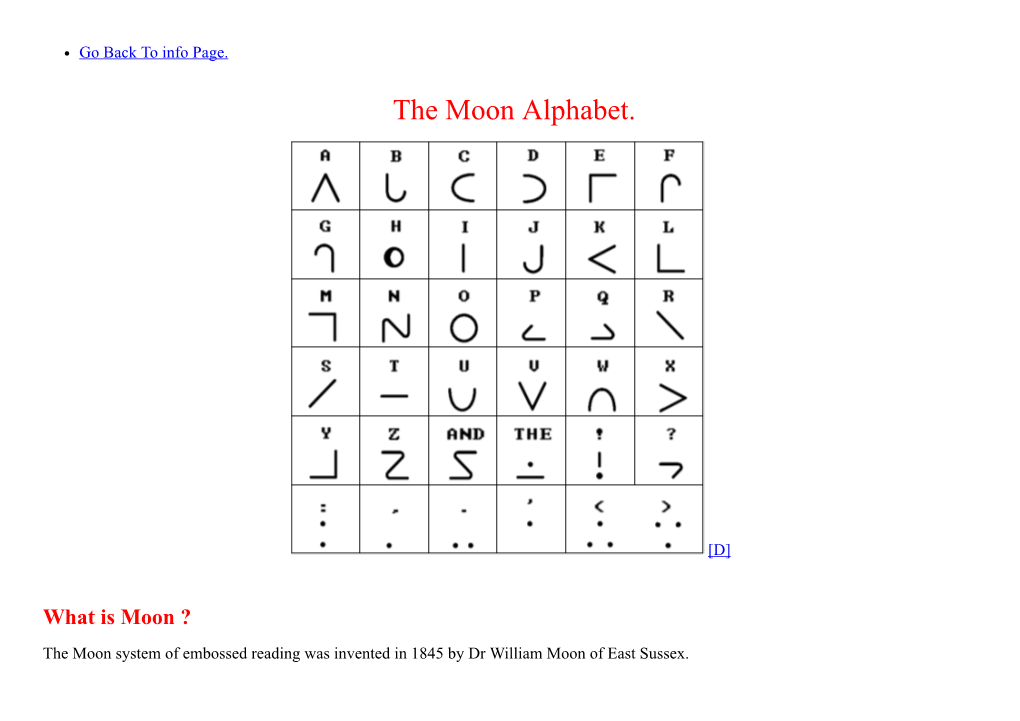

The Moon Alphabet

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

History of the Education of the Blind

HISTORY OF THE EDUCATION OF THE BLIND HISTORY OF THE EDUCATION OF THE BLIND BY W. H. ILLINGWORTH, F.G.T.B. SUPERINTENDENT OP HENSHAW's BLIND ASYLUM, OLD TRAFFORD, MANCHESTER HONORARY SECRETARY TO THE BOARD OF EXAMINERS OF THE COLLEGE OF TEACHERS OF THE BLIND LONDON SAMPSON LOW, MARSTON & COMPANY, LTD. 1910 PRISTKD BY HAZELL, WATSON AND VINEY, LI)., LONDON AND AYLKSBURY. MY BELOVED FRIEND AND COUNSELLOR HENRY J. WILSON (SECRETARY OP THE GARDNER'S TRUST FOR THE BLIND) THIS LITTLE BOOK IS RESPECTFULLY DEDICATED IN THE EARNEST HOPE THAT IT MAY BE THE HUMBLE INSTRUMENT IN GOD'S HANDS OF ACCOMPLISHING SOME LITTLE ADVANCEMENT IN THE GREAT WORK OF THE EDUCATION OF THE BLIND W. II. ILLINGWORTH AUTHOR 214648 PREFACE No up-to-date treatise on the important and interesting " " subject of The History of the Education of the Blind being in existence in this country, and the lack of such a text-book specially designed for the teachers in our blind schools being grievously felt, I have, in response to repeated requests, taken in hand the compilation of such a book from all sources at my command, adding at the same time sundry notes and comments of my own, which the experience of a quarter of a century in blind work has led me to think may be of service to those who desire to approach and carry on their work as teachers of the blind as well equipped with information specially suited to their requirements as circumstances will permit. It is but due to the juvenile blind in our schools that the men and women to whom their education is entrusted should not only be acquainted with the mechanical means of teaching through the tactile sense, but that they should also be so steeped in blind lore that it becomes second nature to them to think of and see things from the blind person's point of view. -

Arab Christians and the Qurʾan from the Origins of Islam to the Medieval Period History of Christian-Muslim Relations

Arab Christians and the Qurʾan from the Origins of Islam to the Medieval Period History of Christian-Muslim Relations Editorial Board Jon Hoover (University of Nottingham) Sandra Toenies Keating (Providence College) Tarif Khalidi (American University of Beirut) Suleiman Mourad (Smith College) Gabriel Said Reynolds (University of Notre Dame) Mark Swanson (Lutheran School of Theology at Chicago) David Thomas (University of Birmingham) VOLUME 35 Christians and Muslims have been involved in exchanges over matters of faith and morality since the founding of Islam. Attitudes between the faiths today are deeply coloured by the legacy of past encounters, and often preserve centuries-old negative views. The History of Christian-Muslim Relations, Texts and Studies presents the surviving record of past encounters in a variety of forms: authoritative, text editions and annotated translations, studies of authors and their works and collections of essays on particular themes and historical periods. It illustrates the development in mutual perceptions as these are contained in surviv- ing Christian and Muslim writings, and makes available the arguments and rhetorical strategies that, for good or for ill, have left their mark on attitudes today. The series casts light on a history marked by intellectual creativity and occasional breakthroughs in communication, although, on the whole beset by misunderstanding and misrepresentation. By making this history better known, the series seeks to contribute to improved recognition between Christians and Muslims in the future. A number of volumes of the History of Christian-Muslim Relations series are published within the subseries Christian-Muslim Relations. A Bibliographical History. The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/hcmr Arab Christians and the Qurʾan from the Origins of Islam to the Medieval Period Edited by Mark Beaumont LEIDEN | BOSTON Cover illustration: translation by Mark Beaumont of Qurʾan 4:171. -

Jtc1/Sc2/Wg2 N4128 L2/11-280

JTC1/SC2/WG2 N4128 L2/11-280 2011-06-29 Universal Multiple-Octet Coded Character Set International Organization for Standardization Organisation Internationale de Normalisation Международная организация по стандартизации Doc Type: Working Group Document Title: Preliminary proposal for encoding the Moon script in the SMP of the UCS Source: Michael Everson Status: Individual Contribution Action: For consideration by JTC1/SC2/WG2 and UTC Date: 2011-06-29 1. Introduction. The Moon System of Embossed Reading, also known as the Moon alphabet, Moon type, or Moon code) is a writing system for the blind which embossed symbols chiefly derived by applying simplifications to the shapes of the letters of the Latin alphabet. It was introduced in 1945 by William Moon (1818–1894), a blind Englishman from Brighton, East Sussex, who founded the Brighton Society for the Blind in 1860. The Moon script is easily learned, particularly by those who have newly become blind and who find Braille daunting. There is evidence that some people who get used to reading by touch are able to transition from Moon script to Braille. Moon was adopted in Britain and in North America, though it was more popular in the 19th century and earlier 20th century than it is today. Nevertheless, a variety of printed literature exists in Moon script, and efforts are being made to adapt modern embossing technology 2. Processing. Short texts in Moon script are written from left to right, but longer embossed texts have boustrophedon directionality: at the end of a line there is a sort of parenthesis which guides the fingers to the next line, which the reader then follows. -

ONIX for Books Codelists Issue 47

ONIX for Books Codelists Issue 47 31 October 2019 DOI: 10.4400/akjh Go to latest Issue All ONIX standards and documentation – including this document – are copyright materials, made available free of charge for general use. A full license agreement (DOI: 10.4400/nwgj) that governs their use is available on the EDItEUR website. All ONIX users should note that this issue of the ONIX codelists does not include support for codelists used only with ONIX version 2.1. ONIX 2.1 remains fully usable, using Issue 36 of the codelists or earlier, and Issue 36 continues to be available via the archive section of the EDItEUR website (https://www.editeur.org/15/Archived-Previous-Releases). These codelists are also available within a multilingual online browser at https://ns.editeur.org/onix. Codelists are revised quarterly. Layout of codelists This document contains ONIX for Books codelists Issue 46, intended primarily for use with ONIX 3.0. The codelists are arranged in a single table for reference and printing. They may also be used as controlled vocabularies, independent of ONIX. This document does not differentiate explicitly between codelists for ONIX 3.0 and those that are used with earlier releases, but lists used only with earlier releases have been removed. For details of which code list to use with which data element in each version of ONIX, please consult the main Specification for the appropriate release. Occasionally, a handful of codes within a particular list are defined as either deprecated, or not valid for use in a particular version of ONIX or with a particular data element. -

ONIX for Books Codelists Issue 46

ONIX for Books Codelists Issue 46 10 July 2019 DOI: 10.4400/akjh Go to latest Issue All ONIX standards and documentation – including this document – are copyright materials, made available free of charge for general use. A full license agreement (DOI: 10.4400/nwgj) that governs their use is available on the EDItEUR website. All ONIX users should note that this issue of the ONIX codelists does not include support for codelists used only with ONIX version 2.1. ONIX 2.1 remains fully usable, using Issue 36 of the codelists or earlier, and Issue 36 continues to be available via the archive section of the EDItEUR website (https://www.editeur.org/15/Archived-Previous-Releases). These codelists are also available within a multilingual online browser at https://ns.editeur.org/onix. Codelists are revised quarterly. Layout of codelists This document contains ONIX for Books codelists Issue 46, intended primarily for use with ONIX 3.0. The codelists are arranged in a single table for reference and printing. They may also be used as controlled vocabularies, independent of ONIX. This document does not differentiate explicitly between codelists for ONIX 3.0 and those that are used with earlier releases, but lists used only with earlier releases have been removed. For details of which code list to use with which data element in each version of ONIX, please consult the main Specification for the appropriate release. Occasionally, a handful of codes within a particular list are defined as either deprecated, or not valid for use in a particular version of ONIX or with a particular data element. -

Transcription of Foreign Tongues

V.-TRANSCRIPTION OF FOREIGN TONGUES. By L. C. WHARTOK. [Read at the dleeting of the Philological rSociety on Friday, Dee. 4, 1925.1 TRANSCRIPTIONis made necessary for one sole reason, the absence of a single universally accepted alphabet, which would obviate all but a small portion of the problem which we have before us. How, for instance, is anyone to refer to events in world-history even in the most cursory and popular way if he is to avoid con- fusing his readers by using forms like “ Meer JaEer ” when quoting Macaulay and “ Mir Dschaffir ” when citing a German contemporary of Macaulay’s. Compare Erskine and Areskine with their nltmerous variants. How, too, is Hertzen, the son of the great Russian writer Iskender (Aleksandr Gertsen) to be perceived to belong to the same family as his father ? I have so far avoided quoting anything in foreign scripts and hope to avoid it in this the first part of my paper, reserving the bulk of it for the critical part. There are, then, certain purposes for which transcription is necessary; I group these under the following five heads, first remarking that I am quite deliberately postponing to a later stage the discussion of the distinction between transliteration and transcription. Now these five groups are as follows:- (a) bibliographical, (b) connected with library catalogues, (c) similarly connected with documentation, (d) connected with historical and other scientific (e.g. phonetic) research, and lastly (e) commercial. If I may, I will justify the addition of this last group first, though some may wish to classify my illustration under Documentation. -

On the Subject of the Hyperlink

Keep Talking and Nobody Explodes Mod The Hyperlink On the Subject of The Hyperlink UdSKWKZFdrU To disarm the module, the defuser needs to describe each character encrypted in the various methods of encryption to the expert, you have to plug the set of characters into a specific link. The video contains a voiceover line which comes from the cards in Modules Against Humanity[1] and you must find out which module is being referred to. Once you have done that, tell your defuser the module that was referenced and submit it. Refer to “Determining Valid Link” to determine which link is used. Refer to “How to Operate The Hyperlink” to tell your defuser how to navigate it. Refer to “Exceptions and Notes” at the bottom for clarifications and confusions. Refer to "References" to find links you may need to solve the module. Encryptions found within The Hyperlink can be any of the following, capitals will always be spelled in the NATO Phonetic Alphabet[2], while lowercase letters will always be single letters. Color Encryption FF0 Necronomicon[16] 0FF Alphabetic Position[3] 800 Ogham 08F American Sign Language[4] 8F8 Pigpen[17] 888 Binary[5] 008 Semaphore[18] F80 Boozleglyphs[6] 880 Standard[19] FFF Braille[7] 88F Standard Galactic Alphabet[20] 8F0 Cube Symbols[8] F08 SYNC-125 [3][21] 00F "Deaf" Semaphore Telegraph[9] F88 Tap Code[22] FF8 Elder Futhark[10] F00 Unown[23] 808 14-Segment Display[11] 0F8 Webdings F0F Lombax[12] 000 Wingdings 0F0 Maritime Flags[13] 088 Wingdings 2 F8F Moon Type[14] 8FF Wingdings 3 080 Morse Code[15] 80F Zoni[24] Keep Talking and Nobody Explodes Mod The Hyperlink Determining Valid Link The valid link can be determined by looking at the square directly underneath the status light: If the square is gray, the link has not been generated yet. -

Arbeitshilfe Schriftcodes Nach ISO 15924

Arbeitsstelle für Standardisierung (AfS) Projekt RDA 5. Februar 2014 Arbeitshilfe Schriftcodes nach ISO 15924 Blau unterlegte deutsche Bezeichnungen benötigen ggf. Überarbeitung - 5.2.2014 Code N° English Name Nom français Deutscher Name Date Afak 439 Afaka afaka Afaka-Schrift 2010-12-21 Aghb 239 Caucasian Albanian aghbanien Alwanische Schrift 2012-10-16 Arab 160 Arabic arabe Arabische Schrift 2004-05-01 Armi 124 Imperial Aramaic araméen impérial Reichsaramäische Schrift 2009-06-01 Armn 230 Armenian arménien Armenische Schrift 2004-05-01 Avst 134 Avestan avestique Avestische Schrift 2009-06-01 Bali 360 Balinese balinais Balinesische Schrift 2006-10-10 Bamu 435 Bamum bamoum Bamun-Schrift 2009-06-01 Bass 259 Bassa Vah bassa Bassa-Schrift 2010-03-26 Batk 365 Batak batik Batak-Schrift 2010-07-23 Beng 325 Bengali bengalî Bengalische Schrift 2004-05-01 Blis 550 Blissymbols symboles Bliss Bliss-Symbol 2004-05-01 Bopo 285 Bopomofo bopomofo Zhuyin Fuhao 2004-05-01 Brah 300 Brahmi brahma Brahmi-Schrift 2010-07-23 Arbeitshilfe AH-003 1 | 7 Code N° English Name Nom français Deutscher Name Date Brai 570 Braille braille Brailleschrift 2004-05-01 Bugi 367 Buginese bouguis Lontara-Schrift 2006-06-21 Buhd 372 Buhid bouhide Buid-Schrift 2004-05-01 Cakm 349 Chakma chakma Chakma-Schrift 2012-02-06 Unified Canadian Aboriginal Vereinheitlichte Silbenzeichen Cans 440 syllabaire autochtone canadien unifié 2004-05-29 Syllabics kanadischer Ureinwohner Cari 201 Carian carien Karische Schrift 2007-07-02 Cham 358 Cham cham (čam, tcham) Cham-Schrift 2009-11-11 Cher -

Gazetteer Service - Application Profile of the Web Feature Service Best Practice

Best Practices Document Open Geospatial Consortium Approval Date: 2012-01-30 Publication Date: 2012-02-17 External identifier of this OGC® document: http://www.opengis.net/doc/wfs-gaz-ap ® Reference number of this OGC document: OGC 11-122r1 Version 1.0 ® Category: OGC Best Practice Editors: Jeff Harrison, Panagiotis (Peter) A. Vretanos Gazetteer Service - Application Profile of the Web Feature Service Best Practice Copyright © 2012 Open Geospatial Consortium To obtain additional rights of use, visit http://www.opengeospatial.org/legal/ Warning This document defines an OGC Best Practices on a particular technology or approach related to an OGC standard. This document is not an OGC Standard and may not be referred to as an OGC Standard. This document is subject to change without notice. However, this document is an official position of the OGC membership on this particular technology topic. Document type: OGC® Best Practice Paper Document subtype: Application Profile Document stage: Approved Document language: English OGC 11-122r1 Contents Page 1 Scope ..................................................................................................................... 13 2 Conformance ......................................................................................................... 14 3 Normative references ............................................................................................ 14 4 Terms and definitions ........................................................................................... 15 5 Conventions -

Chapter 1 Introduction, Statement of the Problem

CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION, STATEMENT OF THE PROBLEM, AND AIM OF THE STUDY 1.1 INTRODUCTION The processes of reading and writing, two of the four language arts along with listening and speaking, are integral features of the lives of many people. While reading and writing are often used as leisure activities, they also play an important role in determining the level of success. "Today, more than ever, those with the ability to communicate through reading and writing have the key that opens doors of employment, recreation, and enlightenment” (Holbrook, Koenig, & Smith 1996:1). Before the invention of the printing press by Gutenberg in the fifteenth century, books were in short supply, as they had to be written manually by monks. Moreover, the cost of books was prohibitive, with the result that only the wealthy could afford to buy and read them. This privileged group included the clergy and certain members of the nobility (Humphrey & Humphrey 1990:31). With the proliferation of printing houses and the production of books, magazines, journals and newspapers on a large scale, anyone who can read has the opportunity to do so. Even if books and other reading materials are unaffordable, libraries throughout the world stock large quantities of reading materials that are easily accessible to the average reader. But reading is certainly not confined to books, newspapers, magazines or journals. Today, many people read hundreds or even thousands of words daily without even looking at a book, newspaper or magazine to do this. They read their mail, street signs, advertisements on billboards, package labels, the wording in television commercials, etc. -

Bibles and Other Sacred Writings in Special Media. Reference Circular. INSTITUTION Library of Congress, Washington, DC

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 443 430 IR 057 862 AUTHOR Nussbaum, Ruth, Comp.; O'Connor, Catherine, Comp.; Herndon, James, Comp.; Emanuel, Shirley, Comp. TITLE Bibles and Other Sacred Writings in Special Media. Reference Circular. INSTITUTION Library of Congress, Washington, DC. National Library Service for the Blind and Physically Handicapped. REPORT NO LC-NLSBPH-99-02 PUB DATE 1999-09-00 NOTE 53p AVAILABLE FROM Reference Section, National Library Service for the Blind and Physically Handicapped, Library of Congress, Washington, DC 20542. PUB TYPE Reference Materials Bibliographies (131) Reference Materials Directories/Catalogs (132) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC03 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Biblical Literature; Blindness; Braille; *Large Type Materials; *Media Adaptation; Physical Disabilities; *Religion IDENTIFIERS *Religious Publications ABSTRACT This reference circular lists Bibles and sacred texts of many world religions, in a variety of languages, translations, and versions, that are available in special media. Commentaries, concordances, liturgies, prayer books, hymnals, and magazines are also listed. Priority was given to citing complete works; portions of works are listed if they are unique in availability, narration, or medium. Braille is grade 2 unless otherwise noted, and large print is 14-point unless otherwise stated. Full-text electronic resources are also listed. The first section alphabetically lists organizations and companies (with contact information) that provide individuals with a visual disability materials that are free, on loan, or for purchase. Prices of the materials listed are subject to change. Subsequent sections list materials, with their book numbers, available through the braille and talking-book program of the National Library Service for the Blind and Physically Handicapped, Library of Congress. -

ISO 15924 - Alphabetical Code List

ISO 15924 - Alphabetical Code List http://www.unicode.org/iso15924/iso15924-codes.html ISO 15924 Code Lists Previous | RA Home | Next Codes for the representation of names of scripts Codes pour la représentation des noms d’écritures Table 1 Alphabetical list of four-letter script codes Liste alphabétique des codets d’écriture à quatre lettres Property Code N° English Name Nom français Date Value Alias Afak 439 Afaka afaka 2010-12-21 Arab 160 Arabic arabe Arabic 2004-05-01 Imperial Armi 124 Imperial Aramaic araméen impérial 2009-06-01 _Aramaic Armn 230 Armenian arménien Armenian 2004-05-01 Avst 134 Avestan avestique Avestan 2009-06-01 Bali 360 Balinese balinais Balinese 2006-10-10 Bamu 435 Bamum bamoum Bamum 2009-06-01 Bass 259 Bassa Vah bassa 2010-03-26 Batk 365 Batak batik Batak 2010-07-23 Beng 325 Bengali bengalî Bengali 2004-05-01 Blis 550 Blissymbols symboles Bliss 2004-05-01 Bopo 285 Bopomofo bopomofo Bopomofo 2004-05-01 Brah 300 Brahmi brahma Brahmi 2010-07-23 Brai 570 Braille braille Braille 2004-05-01 Bugi 367 Buginese bouguis Buginese 2006-06-21 Buhd 372 Buhid bouhide Buhid 2004-05-01 Cakm 349 Chakma chakma Chakma 2012-02-06 Unified Canadian syllabaire autochtone Canadian Cans 440 2004-05-29 Aboriginal Syllabics canadien unifié _Aboriginal Cari 201 Carian carien Carian 2007-07-02 Cham 358 Cham cham (čam, tcham) Cham 2009-11-11 Cher 445 Cherokee tchérokî Cherokee 2004-05-01 Cirt 291 Cirth cirth 2004-05-01 Copt 204 Coptic copte Coptic 2006-06-21 Cprt 403 Cypriot syllabaire chypriote Cypriot 2004-05-01 1 of 6 8/16/12 1:56 PM ISO