On Experiencers and Minimality

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Not So Quirky: on Subject Case in Ice- Landic1

5 Not so Quirky: On Subject Case in Ice- landic 1 JÓHANNES GÍSLI JÓNSSON 1 Introduction The purpose of this paper is to provide an overview of subject case in Icelandic, extending and refining the observations of Jónsson (1997-1998) and some earlier work on this topic. It will be argued that subject case in Icelandic is more predictable from lexical semantics than previous studies have indicated (see also Mohanan 1994 and Narasimhan 1998 for a similar conclusion about Hindi). This is in line with the work of Jónsson (2000) and Maling (2002) who discuss various semantic generalizations about case as- signment to objects in Icelandic. This paper makes two major claims. First, there are semantic restrictions on non-nominative subjects in Icelandic which go far beyond the well- known observation that such subjects cannot be agents. It will be argued that non-nominative case is unavailable to all kinds of subjects that could be described as agent-like, including subjects of certain psych-verbs and intransitive verbs of motion and change of state. 1 I would like to thank audiences in Marburg, Leeds, York and Reykjavík and three anony- mous reviewers for useful comments. This study was supported by grants from the Icelandic Science Fund (Vísindasjóður) and the University of Iceland Research Fund (Rannsóknasjóður HÍ). New Perspectives in Case Theory. Ellen Brandner and Heike Zinsmeister (eds.). Copyright © 2003, CSLI Publications. 129 130 / JOHANNES GISLI JONSSON Second, the traditional dichotomy between structural and lexical case is insufficient in that two types of lexical case must be recognized: truly idio- syncratic case and what we might call semantic case. -

Feature Clusters

Chapter 2 Feature Clusters 1. Introduction The goal of this Chapter is to address certain issues that pertain to the properties of feature clusters and the rules that govern their co-occurrences. Feature clusters come as fully specified (e.g. [+c+m] associated with people in (1a)) and ‘underspecified’ (e.g. [-c] associated with acquaintances in (1a)). Such partitioning of feature clusters raises the question of the implications of notions such as ‘underspecified’ and ‘fully specified’ in syntactic and semantic terms. The sharp contrast between the grammaticality of the middle derivation in (1b) and ungrammaticality of (1c) takes the investigation into rules that regulate the co-realization of feature clusters of the base-verb (1a). Another issue that is discussed in this Chapter is the status of arguments versus adjuncts in the Theta System. This topic is also of importance for tackling the issue of middles in Chapter 4 since – intriguingly enough – whereas (1c) is not an acceptable middle derivation in English, (1d) is. (1a) People[+c+m] don’t send expensive presents to acquaintances[-c] (1b) Expensive presents send easily. (1c) *Expensive presents send acquaintances easily. (1d) Expensive presents do not send easily to foreign countries. In section 2 of this Chapter, the properties of feature clusters with respect to syntax and semantics are examined. Section 3 sets the background for Section 4 by addressing the issue of conditions on thematic roles that have been assumed in the literature. Section 4 deals with conditions that govern the co-occurrences of feature clusters in the Theta System. The discussion in section 4 will necessitate the discussion of adjunct versus argument status of certain phrases. -

From Volition to Obligation: a Force-Involved Change Through Subjectification

Concentric: Studies in Linguistics 42.2 (November 2016): 65-97 DOI: 10.6241/concentric.ling.42.2.03 From Volition to Obligation: A Force-Involved Change through Subjectification Ting-Ting Christina Hsu Chung Yuan Christian University This paper aims to show the importance of subjectification (Traugott 1989, Langacker 1990) for the emergence of deontic modals with the development of the deontic modal ai3 in Southern Min. Materials under examination are early texts of Southern Min in the playscripts of Li Jing Ji ‘The Legend of Litchi Mirror’ and a collection of folk stories in contemporary Southern Min. The deontic modal ai3 in Southern Min is assumed to have developed from the intentional ai3 through subjectification on the basis of their parallel force-dynamic structures which represent the preservation of their force interactions throughout the development of the deontic modal ai3 (Talmy 2000). Because subjectifica- tion is also known to contribute to the emergence of epistemic modals (Traugott 1989, Sweetser 1990), it can then be seen as a general process through which force-involved modals can emerge. Key words: subjectification, force dynamics, volition, deontic modal, intentional verb 1. Introduction The structure of human language is reflective of human cognition (Berlin & Kay 1969, Sweetser 1990) and determined by the perceptual system (Fillmore 1971, Clark 1973). The development of modals is also affected by cognitive processes. One of these processes is subjectification, which increases speakers’ involvement in the proposition or grounding of a predication (Traugott 1989, Langacker 1990). Subjec- tification is assumed to contribute to the emergence of epistemic modals since a speaker’s perspectives or roles are specifically important for epistemic modals (Sweetser 1990). -

1 the Syntax of Scope Anna Szabolcsi January 1999 Submitted to Baltin—Collins, Handbook of Contemporary Syntactic Theory

1 The Syntax of Scope Anna Szabolcsi January 1999 Submitted to Baltin—Collins, Handbook of Contemporary Syntactic Theory 1. Introduction This chapter reviews some representative examples of scopal dependency and focuses on the issue of how the scope of quantifiers is determined. In particular, we will ask to what extent independently motivated syntactic considerations decide, delimit, or interact with scope interpretation. Many of the theories to be reviewed postulate a level of representation called Logical Form (LF). Originally, this level was invented for the purpose of determining quantifier scope. In current Minimalist theory, all output conditions (the theta-criterion, the case filter, subjacency, binding theory, etc.) are checked at LF. Thus, the study of LF is enormously broader than the study of the syntax of scope. The present chapter will not attempt to cover this broader topic. 1.1 Scope relations We are going to take the following definition as a point of departure: (1) The scope of an operator is the domain within which it has the ability to affect the interpretation of other expressions. Some uncontroversial examples of an operator having scope over an expression and affecting some aspect of its interpretation are as follows: Quantifier -- quantifier Quantifier -- pronoun Quantifier -- negative polarity item (NPI) Examples (2a,b) each have a reading on which every boy affects the interpretation of a planet by inducing referential variation: the planets can vary with the boys. In (2c), the teachers cannot vary with the boys. (2) a. Every boy named a planet. `for every boy, there is a possibly different planet that he named' b. -

Dative Constructions in Romance and Beyond

Dative constructions in Romance and beyond Edited by Anna Pineda Jaume Mateu language Open Generative Syntax 7 science press Open Generative Syntax Editors: Elena Anagnostopoulou, Mark Baker, Roberta D’Alessandro, David Pesetsky, Susi Wurmbrand In this series: 1. Bailey, Laura R. & Michelle Sheehan (eds.). Order and structure in syntax I: Word order and syntactic structure. 2. Sheehan, Michelle & Laura R. Bailey (eds.). Order and structure in syntax II: Subjecthood and argument structure. 3. BacskaiAtkari, Julia. Deletion phenomena in comparative constructions: English comparatives in a crosslinguistic perspective. 4. Franco, Ludovico, Mihaela Marchis Moreno & Matthew Reeve (eds.). Agreement, case and locality in the nominal and verbal domains. 5. Bross, Fabian. The clausal syntax of German Sign Language: A cartographic approach. 6. Smith, Peter W., Johannes Mursell & Katharina Hartmann (eds.). Agree to Agree: Agreement in the Minimalist Programme. 7. Pineda, Anna & Jaume Mateu (eds.). Dative constructions in Romance and beyond. ISSN: 25687336 Dative constructions in Romance and beyond Edited by Anna Pineda Jaume Mateu language science press Pineda, Anna & Jaume Mateu (eds.). 2020. Dative constructions in Romance and beyond (Open Generative Syntax 7). Berlin: Language Science Press. This title can be downloaded at: http://langsci-press.org/catalog/book/258 © 2020, the authors Published under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Licence (CC BY 4.0): http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ISBN: 978-3-96110-249-5 (Digital) 978-3-96110-250-1 -

A PROLOG Implementation of Government-Binding Theory

A PROLOG Implementation of Government-Binding Theory Robert J. Kuhns Artificial Intelligence Center Arthur D. Little, Inc. Cambridge, MA 02140 USA Abstrae_~t For the purposes (and space limitations) of A parser which is founded on Chomskyts this paper we only briefly describe the theories Government-Binding Theory and implemented in of X-bar, Theta, Control, and Binding. We also PROLOG is described. By focussing on systems of will present three principles, viz., Theta- constraints as proposed by this theory, the Criterion, Projection Principle, and Binding system is capable of parsing without an Conditions. elaborate rule set and subcategorization features on lexical items. In addition to the 2.1 X-Bar Theory parse, theta, binding, and control relations are determined simultaneously. X-bar theory is one part of GB-theory which captures eross-categorial relations and 1. Introduction specifies the constraints on underlying structures. The two general schemata of X-bar A number of recent research efforts have theory are: explicitly grounded parser design on linguistic theory (e.g., Bayer et al. (1985), Berwick and Weinberg (1984), Marcus (1980), Reyle and Frey (1)a. X~Specifier (1983), and Wehrli (1983)). Although many of these parsers are based on generative grammar, b. X-------~X Complement and transformational grammar in particular, with few exceptions (Wehrli (1983)) the modular The types of categories that may precede or approach as suggested by this theory has been follow a head are similar and Specifier and lagging (Barton (1984)). Moreover, Chomsky Complement represent this commonality of the (1986) has recently suggested that rule-based pre-head and post-head categories, respectively. -

Principles and Parameters Set out from Europe

Principles and Parameters Set Out from Europe Mark Baker MIT Linguistics 50th Anniversary, 9 December 2011 1. The Opportunity Afforded (1980-1995) The conception of universal principles plus finite discrete parameters of variation offered: The hope and challenge of simultaneously doing justice to both the similarities and the differences among languages. The discovery and expectation of patterns in crosslinguistic variation. These were first presented with respect to “medium- sized” differences in European languages: The subjacency parameter (Rizzi, 1982) The pro-drop parameter (Chomsky, 1981; Kayne, 1984; Rizzi, 1982) They were then perhaps extended to the largest differences among languages around the world: The configurationality parameter(s) (Hale, 1983) “The more languages differ, the more they are the same” Example 1: Mohawk (Baker, 1988, 1991, 1996) Mohawk seems nonconfigurational, with no “syntactic” evidence of a VP containing the object and not the subject: (1) a. Sak wa-ha-hninu-’ ne ka-nakt-a’. Sak FACT-3mS-buy-PUNC NE 3n-bed-NSF b. Sak kanakta wahahninu’ c. Kanakta’ wahahninu’ ne Sak d. Kanakta’ Sak wahahninu’ e. Wahahninu’ ne Sak ne kanakta’ f. Wahahninu’ ne kanakta’ ne Sak g. Wahahninu’ ne kanakta’ h. Kanakta’ wahahninu’ i. Sak wahahninu’ j. Wahahninu’ ne Sak k. Wahahninu. All: ‘Sak/he bought a bed/it.’ There are also no differences between subject and object in binding (Condition C, neither c- commands the other) or wh-extraction (both are islands, no “subject condition”) (Baker 1992) Mohawk is polysynthetic (agreement, noun incorporation, applicative, causative, directionals…): (2) a. Sak wa-ha-nakt-a-hninu-’ Sak FACT-3mS-bed-Ø-buy-PUNC ‘Sak bought the bed.’ 1 b. -

The Concept of Intentional Action in the Grammar of Kathmandu Newari

THE CONCEPT OF INTENTIONAL ACTION IN THE GRAMMAR OF KATHMANDU NEWARI by DAVID J. HARGREAVES A DISSERTATION Presented to the Department of Linguistics and the Graduate School of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy August 1991 ii APPROVED: Dr. Scott DeLancey iii An Abstract of the Dissertation of David J. Hargreaves for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Linguistics to be taken August 1991 Title: THE CONCEPT OF INTENTIONAL ACTION IN THE GRAMMAR OF KATHMANDU NEWARI Approved: Dr. Scott DeLancey This study describes the relationship between the concept of intentional action and the grammatical organization of the clause in Kathmandu Newari, a Tibeto-Burman language spoken primarily in the Kathmandu valley of Nepal. In particular, the study focuses on the conceptual structure of "intentional action" along with the lexical, morphological, and syntactic reflexes of this notion in situated speech. The construal of intentional action consists of two distinct notions: one involving the concept of self-initiated force and the other involving mental representation or awareness. The distribution of finite inflectional forms for verbs results from the interaction of these two notions with a set of evidential/discourse principles which constrain the attribution of intentional action to certain discourse roles in situated interaction. iv VITA NAME OF AUTHOR: David J. Hargreaves PLACE OF BIRTH: Detroit, Michigan DATE OF BIRTH: March 10, 1955 GRADUATE AND UNDERGRADUATE -

How to Understand Conjugation in Japanese, Words That Form the Predicate, Such As Verbs and Adjectives, Change Form According to Their Meaning and Function

How to Understand Conjugation In Japanese, words that form the predicate, such as verbs and adjectives, change form according to their meaning and function. This change of word form is called conjugation, and words that change their forms are called conjugational words. Yōgen (用言: roughly verbs and adjectives) Complex Japanese predicates can be divided into several “words” when one looks at formal characteristics such as accent and breathing. (Here, a “word” is almost equivalent to an accent unit, or the smallest a unit governed by breathing pauses, and is larger than the word described in school grammar.) That is, the Japanese predicate does not consist of one word; rather it is a complex of yōgen, made up of a series of words. Each of the “words” that make up the predicate (i.e., yōgen complex) undergoes word form change, and words in a similar category may be strung together in a row. Therefore, altogether there is quite a wide variety of forms of predicates. Some people do not divide the yōgen complex into words, however. They treat the predicate as a single entity, and call the entire variety of changes conjugation. Some try to integrate all variety of such word form change into a single chart. This chart not only tends to be enormous in size, but also each word shows the same inflection cyclically. There is much redundancy in this approach. When dealing with Japanese, it will be much simpler if one separates the description of the order in which the components of the predicate (yōgen complex) appear and the description of the word form change of individual words. -

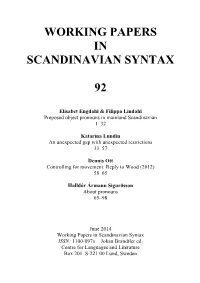

Working Papers in Scandinavian Syntax 92 (2014) 1–32 ! 2

WORKING PAPERS IN SCANDINAVIAN SYNTAX 92 Elisabet Engdahl & Filippa Lindahl Preposed object pronouns in mainland Scandinavian 1–32 Katarina Lundin An unexpected gap with unexpected restrictions 33–57 Dennis Ott Controlling for movement: Reply to Wood (2012) 58–65 Halldór Ármann Sigur!sson About pronouns 65–98 June 2014 Working Papers in Scandinavian Syntax ISSN: 1100-097x Johan Brandtler ed. Centre for Languages and Literature Box 201 S-221 00 Lund, Sweden Preface: Working Papers in Scandinavian Syntax is an electronic publication for current articles relating to the study of Scandinavian syntax. The articles appearing herein are previously unpublished reports of ongoing research activities and may subsequently appear, revised or unrevised, in other publications. The WPSS homepage: http://project.sol.lu.se/grimm/working-papers-in-scandinavian-syntax/ The 93rd volume of WPSS will be published in December 2014. Papers intended for publication should be submitted no later than October 15, 2014. Contact: Johan Brandtler, editor [email protected]! Preposed object pronouns in mainland Scandinavian* Elisabet Engdahl & Filippa Lindahl University of Gothenburg Abstract We report on a study of preposed object pronouns using the Scandinavian Dialect Corpus. In other Germanic languages, e.g. Dutch and German, preposing of un- stressed object pronouns is restricted, compared with subject pronouns. In Danish, Norwegian and Swedish, we find several examples of preposed pronouns, ranging from completely unstressed to emphatically stressed pronouns. We have investi- gated the type of relation between the anaphoric pronoun and its antecedent and found that the most common pattern is rheme-topic chaining followed by topic- topic chaining and left dislocation with preposing. -

Discernment and Volition: Two Aspects of Politeness

Volume 3 Issue 1 INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF HUMANITIES AND June 2016 CULTURAL STUDIES ISSN 2356-5926 Discernment and Volition: Two Aspects of Politeness Bikhtiyar Omar Fattah English Department,Faculty of Education,University of Koya Kurdistan Region, Iraq [email protected] Abstract This study is titled "Discernment and Volition: Two aspects of politeness". It aims at examining two problematic concepts (Discernment and Volition) by presenting how they have been considered in the politeness studies and how they can be enriched with new senses that can enable them to be applicable in all languages. This study consists of seven sections. At the very beginning, it gains deeper insight into the concepts of Discernment and Volition to be critically reconsidered. Then, it compares them to their closest concepts politic and Polite to present the points of similarities and differences between them. After that, both Discernment-dominated and Volitional dominated cultures will be considered. This study also moves on to identifying the elements that constitute Discernment, and those that constitute volitional interactions, as well as clarifying the process of their interpretation within the context. Finally, this study comprehensively introduces the methodology that can work for examining Discernment and Volition, clarifies the process of data collection and illustrates the process of data analysis. Keywords: Discernment, Volition, Culturally-recommended utterances, Honorifics, and Rationality. http://www.ijhcs.com/index Page 385 Volume 3 Issue 1 INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF HUMANITIES AND June 2016 CULTURAL STUDIES ISSN 2356-5926 1. Introduction Discernment and Volition are two aspects of language use that they function as two bases of making polite interactions. -

Handout 1: Basic Notions in Argument Structure

Handout 1: Basic Notions in Argument Structure Seminar The verb phrase and the syntax-semantics interface , Andrew McIntyre 1 Introduction 1.1 Some basic concepts Part of the knowledge we have about certain linguistic expressions is that they must or may appear with certain other expressions (their arguments ) in order to be interpreted semantically and in order to produce a syntactically well-formed phrase/sentence. (1) John put the book near the door put takes John, the book and near the door as arguments near takes the door and arguably the book as arguments (2) Fred’s reliance on Mary reliance takes on Mary and Fred as arguments (3) John is fond of his stamp collection fond takes his stamp collection and John as arguments An expression taking an argument is called a predicate in modern & philosophical terminology (distinguish from old terminology where predicate = verb phrase). An argument can itself be a predicate (4) Gertrude got angry (in some theories, angry is an argument of get , and Gertrude is an argument of both get and angry ) Some linguists say that arguments can be shared by two predicates, e.g. in (1) the book might be taken to be an argument of both put and near . Argument structure (valency) : the (study of) the arguments taken by expressions. In syntax, we say a predicate (e.g. a verb) has, takes, subcategorises for, selects this or that (or so-and-so many) argument(s). You cannot say you know a word unless you know its argument structure. A word’s argument structure must be mentioned in its lexical entry (=the information associated with the word in the mental lexicon , i.e.