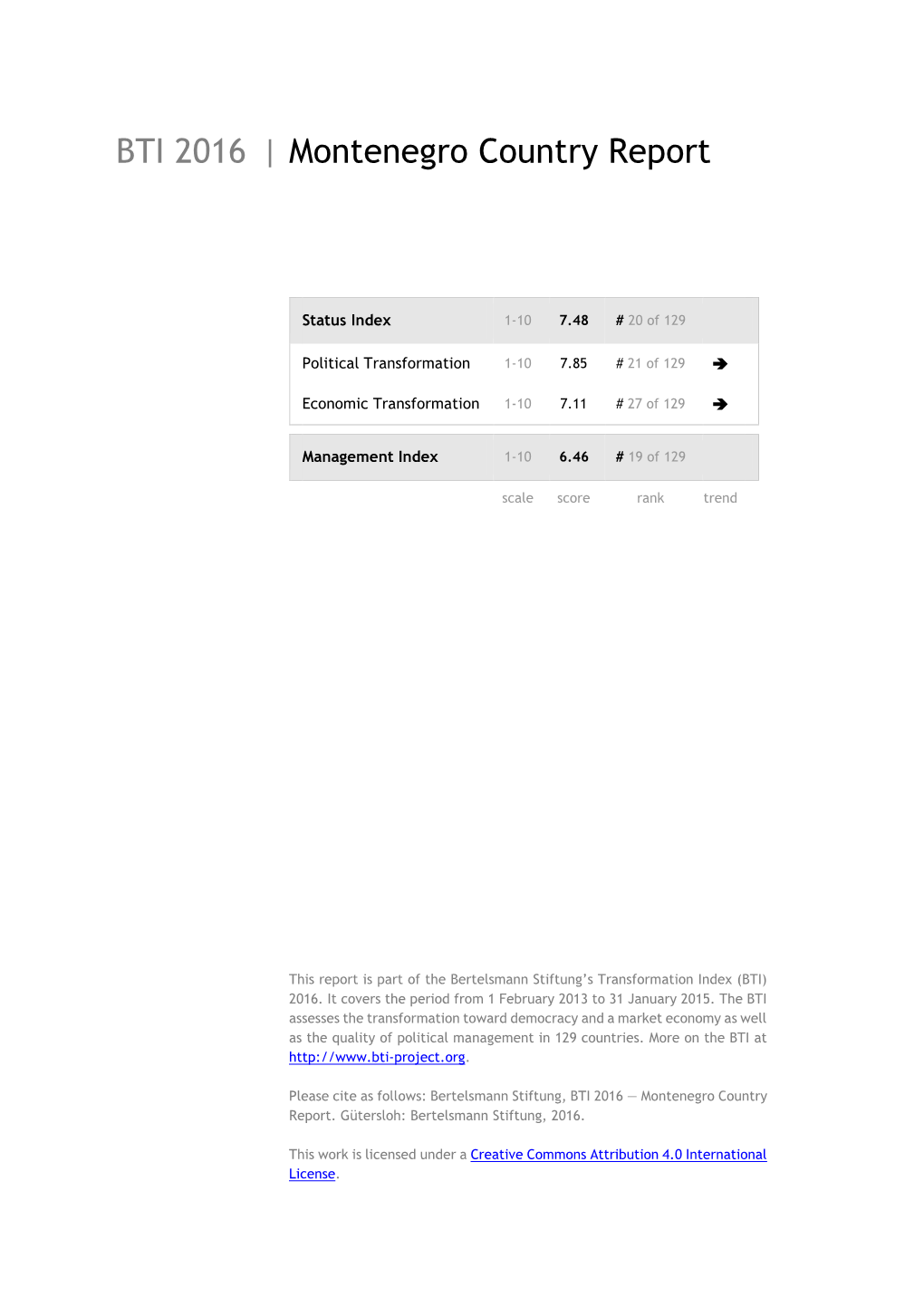

Montenegro Country Report BTI 2016

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Montenegro Country Report BTI 2014

BTI 2014 | Montenegro Country Report Status Index 1-10 7.50 # 22 of 129 Political Transformation 1-10 7.90 # 23 of 129 Economic Transformation 1-10 7.11 # 28 of 129 Management Index 1-10 6.51 # 18 of 129 scale score rank trend This report is part of the Bertelsmann Stiftung’s Transformation Index (BTI) 2014. It covers the period from 31 January 2011 to 31 January 2013. The BTI assesses the transformation toward democracy and a market economy as well as the quality of political management in 129 countries. More on the BTI at http://www.bti-project.org. Please cite as follows: Bertelsmann Stiftung, BTI 2014 — Montenegro Country Report. Gütersloh: Bertelsmann Stiftung, 2014. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. BTI 2014 | Montenegro 2 Key Indicators Population M 0.6 HDI 0.791 GDP p.c. $ 14206.2 Pop. growth1 % p.a. 0.1 HDI rank of 187 52 Gini Index 28.6 Life expectancy years 74.5 UN Education Index 0.838 Poverty3 % 0.0 Urban population % 63.5 Gender inequality2 - Aid per capita $ 163.1 Sources: The World Bank, World Development Indicators 2013 | UNDP, Human Development Report 2013. Footnotes: (1) Average annual growth rate. (2) Gender Inequality Index (GII). (3) Percentage of population living on less than $2 a day. Executive Summary Preparations for EU accession have dominated the political agenda in Montenegro during the period under review. Recognizing the progress made by the country on seven key priorities identified in its 2010 opinion, the European Commission in October 2011 proposed to start accession negotiations. -

Izvještaj O Medijskom Predstavljanju Za Predsjedničke Izbore 2018

Crna Gora AGENCIJA ZA ELEKTRONSKE MEDIJE Broj: 02 – 929 Podgorica, 23.04.2018.godine IZVJEŠTAJ O MEDIJSKOM PREDSTAVLJANJU TOKOM KAMPANJE ZA IZBORE ZA PREDSJEDNIKA CRNE GORE ODRŽANE 15. APRILA 2018. GODINE Zakonski okvir Zakon o izboru odbornika i poslanika1, u okviru Poglavlja VII Predstavljanje podnosilaca izbornih lista i kandidata sa izbornih lista (čl. 50 - 64b.), reguliše prava i obaveze elektronskih i štampanih medija u toku predizborne kampanje. Predstavljanje kandidata posredstvom javnih emitera, u skladu sa ovim zakonom, vrši se na osnovu pravila koja donosi nadležni organ javnog emitera, odnosno komercijalnog i neprofitnog emitera. Pravila se moraju donijeti i učiniti dostupnim javnosti u roku od najkasnije 10 dana od dana raspisivanja izbora. Pravo na medijsko praćenje u predizbornoj kampanji počinje od dana potvrđivanja izborne liste učesnika predizborne kampanje i prestaje 24 časa prije dana održavanja izbora. Zakon propisuje da se od dana potvrđivanja izborne liste, odnosno kandidature, stiče pravo da se posredstvom nacionalnog javnog emitera Radio Televizija Crne Gore, kao i posredstvom regionalnih i lokalnih javnih emitera, u okviru istih dnevnih termina, odnosno rubrika, svakodnevno, u jednakom trajanju i besplatno obavještavaju građani o kandidatima, programima i aktivnostima. Radio Televizija Crne Gore, regionalni i lokalni javni emiteri obavezni su da, u vrijeme izborne kampanje, u blokovima komercijalnog marketinga, svakodnevno, u jednakom trajanju i u istom terminu, obezbijede besplatno i ravnopravno objavljivanje najava svih promotivnih skupova podnosilaca izbornih lista. Takođe, javni emiteri su obavezni da u blokovima komercijalnog marketinga obezbijede emitovanje: - političko-propagandnih TV-klipova, odnosno audio-klipova, u obimu ne manjem od 200 sekundi dnevno, zavisno od planiranog broja reklamnih blokova političkog marketinga; - trominutnih izvještaja sa promotivnog skupa, dva puta dnevno, u terminima odmah nakon centralnih večernjih informativnih emisija televizije i radija. -

ESS9 Appendix A3 Political Parties Ed

APPENDIX A3 POLITICAL PARTIES, ESS9 - 2018 ed. 3.0 Austria 2 Belgium 4 Bulgaria 7 Croatia 8 Cyprus 10 Czechia 12 Denmark 14 Estonia 15 Finland 17 France 19 Germany 20 Hungary 21 Iceland 23 Ireland 25 Italy 26 Latvia 28 Lithuania 31 Montenegro 34 Netherlands 36 Norway 38 Poland 40 Portugal 44 Serbia 47 Slovakia 52 Slovenia 53 Spain 54 Sweden 57 Switzerland 58 United Kingdom 61 Version Notes, ESS9 Appendix A3 POLITICAL PARTIES ESS9 edition 3.0 (published 10.12.20): Changes from previous edition: Additional countries: Denmark, Iceland. ESS9 edition 2.0 (published 15.06.20): Changes from previous edition: Additional countries: Croatia, Latvia, Lithuania, Montenegro, Portugal, Slovakia, Spain, Sweden. Austria 1. Political parties Language used in data file: German Year of last election: 2017 Official party names, English 1. Sozialdemokratische Partei Österreichs (SPÖ) - Social Democratic Party of Austria - 26.9 % names/translation, and size in last 2. Österreichische Volkspartei (ÖVP) - Austrian People's Party - 31.5 % election: 3. Freiheitliche Partei Österreichs (FPÖ) - Freedom Party of Austria - 26.0 % 4. Liste Peter Pilz (PILZ) - PILZ - 4.4 % 5. Die Grünen – Die Grüne Alternative (Grüne) - The Greens – The Green Alternative - 3.8 % 6. Kommunistische Partei Österreichs (KPÖ) - Communist Party of Austria - 0.8 % 7. NEOS – Das Neue Österreich und Liberales Forum (NEOS) - NEOS – The New Austria and Liberal Forum - 5.3 % 8. G!LT - Verein zur Förderung der Offenen Demokratie (GILT) - My Vote Counts! - 1.0 % Description of political parties listed 1. The Social Democratic Party (Sozialdemokratische Partei Österreichs, or SPÖ) is a social above democratic/center-left political party that was founded in 1888 as the Social Democratic Worker's Party (Sozialdemokratische Arbeiterpartei, or SDAP), when Victor Adler managed to unite the various opposing factions. -

Sustainability Index 2006/2007

MEDIA SUSTAINABILITY INDEX 2006/2007 The Development of Sustainable Independent Media in Europe and Eurasia MEDIA SUSTAINABILITY INDEX 2006/2007 The Development of Sustainable Independent Media in Europe and Eurasia www.irex.org/msi Copyright © 2007 by IREX IREX 2121 K Street, NW, Suite 700 Washington, DC 20037 E-mail: [email protected] Phone: (202) 628-8188 Fax: (202) 628-8189 www.irex.org Project managers: Mark Whitehouse and Drusilla Menaker IREX Project and Editorial Support: Blake Saville, Drusilla Menaker, Mark Whitehouse, Michael Clarke, Leon Morse Copyeditor: Kelly Kramer, WORDtoWORD Editorial Services Design and layout: OmniStudio Printer: Kirby Lithographic Company, Inc. Notice of Rights: Permission is granted to display, copy, and distribute the MSI in whole or in part, provided that: (a) the materials are used with the acknowledgement “The Media Sustainability Index (MSI) is a product of IREX with funding from USAID.”; (b) the MSI is used solely for personal, noncommercial, or informational use; and (c) no modifications of the MSI are made. Acknowledgment: This publication was made possible through support provided by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) under Cooperative Agreement No. DGS-A-00-99-00015-00. Disclaimer: The opinions expressed herein are those of the panelists and other project researchers and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or IREX. ISSN 1546-0878 ii USAID The United States Agency for International Development (USAID) is an independent agency that provides economic, development, -

THE WARP of the SERBIAN IDENTITY Anti-Westernism, Russophilia, Traditionalism

HELSINKI COMMITTEE FOR HUMAN RIGHTS IN SERBIA studies17 THE WARP OF THE SERBIAN IDENTITY anti-westernism, russophilia, traditionalism... BELGRADE, 2016 THE WARP OF THE SERBIAN IDENTITY Anti-westernism, russophilia, traditionalism… Edition: Studies No. 17 Publisher: Helsinki Committee for Human Rights in Serbia www.helsinki.org.rs For the publisher: Sonja Biserko Reviewed by: Prof. Dr. Dubravka Stojanović Prof. Dr. Momir Samardžić Dr Hrvoje Klasić Layout and design: Ivan Hrašovec Printed by: Grafiprof, Belgrade Circulation: 200 ISBN 978-86-7208-203-6 This publication is a part of the project “Serbian Identity in the 21st Century” implemented with the assistance from the Open Society Foundation – Serbia. The contents of this publication are the sole responsibility of the Helsinki Committee for Human Rights in Serbia, and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Open Society Foundation – Serbia. CONTENTS Publisher’s Note . 5 TRANSITION AND IDENTITIES JOVAN KOMŠIĆ Democratic Transition And Identities . 11 LATINKA PEROVIĆ Serbian-Russian Historical Analogies . 57 MILAN SUBOTIĆ, A Different Russia: From Serbia’s Perspective . 83 SRĐAN BARIŠIĆ The Role of the Serbian and Russian Orthodox Churches in Shaping Governmental Policies . 105 RUSSIA’S SOFT POWER DR. JELICA KURJAK “Soft Power” in the Service of Foreign Policy Strategy of the Russian Federation . 129 DR MILIVOJ BEŠLIN A “New” History For A New Identity . 139 SONJA BISERKO, SEŠKA STANOJLOVIĆ Russia’s Soft Power Expands . 157 SERBIA, EU, EAST DR BORIS VARGA Belgrade And Kiev Between Brussels And Moscow . 169 DIMITRIJE BOAROV More Politics Than Business . 215 PETAR POPOVIĆ Serbian-Russian Joint Military Exercise . 235 SONJA BISERKO Russia and NATO: A Test of Strength over Montenegro . -

“Thirty Years After Breakup of the SFRY: Modern Problems of Relations Between the Republics of the Former Yugoslavia”

RUSSIAN ACADEMY OF SCIENCES, INSTITUTE OF ECONOMICS “Thirty years after breakup of the SFRY: modern problems of relations between the republics of the former Yugoslavia” 15th independence anniversary of Montenegro: achievements and challenges Prof. dr Gordana Djurovic University of Monenegro 21 May 2021 1 An overview: from Doclea to the Kingdom of Montenegro (1) • During the Roman Empire, the territory of Montenegro was actually the territory of Duklja (DOCLEA). Doclea was originally the name of the Roman city on the site of modern Podgorica (Ribnica), built by Roman Emperor Diocletian, who hailed from this region of Roman Dalmatia. • With the arrival of the Slovenes in the 7th century, Christianity quickly gained primacy in this region. • Doclea (Duklja) gradually became a Principality (Knezevina - Arhontija) in the second part of the IX century. • The first known prince (knez-arhont) was Petar (971-990), (or Petrislav, according to Kingdom of Doclea by 1100, The Chronicle of the Priest of Dioclea or Duklja , Ljetopis popa Dukljanina, XIII century). In 1884 a during the rule of King Constantine Bodin lead stamp was found, on which was engraved in Greek "Petar prince of Doclea"; In that period, Doclea (Duklja) was a principality (Byzantine vassal), and Petar was a christianized Slav prince (before the beginning of the Slavic mission of Cirilo and Metodije in the second part of the IX century (V.Nikcevic, Crnogorski jezik, 1993). • VOJISLAVLJEVIĆ DYNASTY (971-1186) - The first ruler of the Duklja state was Duke Vladimir (990 – 1016.). His successor was duke Vojislav (1018-1043), who is considered the founder of Vojislavljević dynasty, the first Montenegrin dynasty. -

6.7 Mediter En Cifras

5 balance ingles ES07:4 Dossier 13/9/07 11:11 Página 189 Mediterranean Politics | Turkey-Balkans Montenegro: The Difficult Rebirth of a Mediterranean State Jean-Arnault Dérens, After signing the Dayton Peace Agreement in December Editor in Chief 1995, Milo Djukanovic began a process of progressive Courrier des Balkans, Arcueil distancing. He began to approach the West as well Panorama as Montenegrin separatist movements headed by the Liberal Alliance of Montenegro (LSCG). In the summer With Montenegro’s independence resulting from a of 1996, the final rupture came with the break-up of referendum held on 21st May 2006, Europe and the the Democratic Party of Socialists (DPS), successor Mediterranean Basin gained a new State. In reality, of the former Communists League. Milo Djukanovic 2007 it is the rebirth of a State, since the full independence and his followers kept control of the party, obliging Med. of the small mountain principality had been Momir Bulatovic to create a new party, the Socialist recognised at the Congress of Berlin in 1878. People’s Party (SNP). At the presidential elections of Montenegro was admitted to the League of Nations autumn 1996, Milo Djukanovic defeated his rival. in 1918, despite its annexation that same year The subsequent years, particularly marked by the into the new Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Kosovo crisis and NATO bombings in the spring of Slovenes. Within the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, 1999 – which did not spare Montenegro – accentuated 189 Montenegro had enjoyed near independence for this political evolution. Milo Djukanovic posed as an many years. Faced with serious environmental advocate of Montenegrin ‘sovereignty,’ even if he had challenges and the weight of organised crime, this not yet uttered the word independence. -

EC: “In Montenegro Still No Confiscation of Assets for Corruption Offences”

ISSN 1800-7678 EuropeanElectronic monthly magazine pulse for European Integration – No 85, October 2012 FOCUS OF THIS ISSUE EC: “In Montenegro still no confiscation of assets for corruption offences” interview President of the Monitoring Centre Zlatko Vujović analysis Will the election of the new Prime Minister influence the course of negotiations with EU? region How justified are the demands to revise EU visa policy towards Western Balkans? European pulse Foreword / Calendar Foreword: No surprises Coalition “European Montenegro” won the 14 October parliamentary elections, but for the first time in 11 years the alliance between Democratic Party of Socialists (DPS) and Social-democratic party (SDP) failed to win the absolute majority and will need support of minority parties to form the government. A few days earlier, the European Commission (EC) published its annual progress report on Montenegro, recommending urgent amendments to the constitution in order to push through the reform of judiciary. It also asked for a more substantial track record in the fight against organised crime and high-level corruption. Both were to be expected. The opposition, somewhat refreshed and seemingly more serious, didn’t manage to displace DPS, always prone to abuse of public resources in election campaigns – in the only country member of the Council of Europe which never changed the government since the fall of the Berlin Wall. For many, EC’s 2012 report Vladan Žugić on Montenegro was too complimentary, but it would have been hard for Štefan Füle to reverse the words of praise for Montenegro's progress that the EC published only a few months earlier, in its May report, to which Montenegro owes the opening of membership negotiations. -

Divided to the Detriment of the Profession

THE EDITORS’ ROLE IN MEDIA INTEGRITY PROTECTION IN MONTENEGRO DIVIDED TO THE DETRIMENT OF THE PROFESSION by DANIELA VRANKOVIĆ INTRODUCTION The editors in the media in Montenegro, particularly the editors at public broadcaster RTCG, are vulnerable to political divisions and conflicts in the coun- try. That is well illustrated by the resignation of the editors at TVCG as a conse- quence of negotiations between political parties in early 2016.1 No one mentioned the law, the legal procedure or the public broadcaster’s independence, although all of this is strictly regulated in the TVCG’s legal framework. Yet, its programme along with part of the private media was perceived as a stronghold of the ruling Democratic Party of Socialists (DPS), and that is why the opposition insisted on the resignations in the first place. On the other hand, the rest of the media are seen as government opponents. It is of no relevance whether this division is true in its particulars; the fact is that it prevents the media community from reaching agreement and unity in most matters related to journalism. Media regulations in Montenegro hardly mention editors. Basically, they have no delegated responsibilities. No legal responsibility means no legal rights. Self-regulation also pays no special attention to the status of editors. Several non-governmental organisations have proposed amendments to media legisla- tion, some of which have to do with the role of editors in the media. However, this is not likely to become a subject of public discussion any time soon. In this kind of situation, the public interest, supposedly guarded by editors, is rarely the interest that prevails. -

Montenegro Integration Perspectives and Synergic Effects Of

Integration Perspectives and Synergic Effects of European Transformation in the Countries Targeted by EU Enlargement and Neighbourhood Policies Montenegro Jelena Džankiü Jadranka Kaluÿeroviü, Ivana Vojinoviü, Ana Krsmanoviü, Milica Dakoviü, Gordana Radojeviü, Ivan Jovetiü, Vojin Goluboviü, Mirza Muleškoviü, Milika Mirkoviü, ISSP – Institute for Strategic Studies and Prognosis Bosiljka Vukoviü June 2008 TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER 1 POLITICAL TRANSFORMATION PROCESS IN MONTENEGRO ............. 4 1.1 Introduction........................................................................................................... 5 1.2 The Creation of Democratic Institutions and Their Functioning ............................. 7 1.2.1 Political institutions in Montenegro throughout history: the effect of political traditions on the development of democratic institutions................................................ 7 1.2.2 The constitutional establishment of Montenegro .......................................... 12 1.2.3 Observations ................................................................................................ 26 1.3 The Implementation of the EU’s Democratic Requirements................................. 27 1.3.1 Transparency ............................................................................................... 27 1.3.2 Decision-making processes .......................................................................... 29 1.3.3 Minority rights............................................................................................ -

Fond Za Zdravstveno Osiguranje Crne Gore

Fond za zdravstveno osiguranje Crne Gore IZVJEŠTAJ O RADU FONDA ZA ZDRAVSTVENO OSIGURANJE CRNE GORE ZA 2019. GODINU Podgorica, mart 2020. godine Adresa: Ul. Vaka Đurovića bb 81000 Podgorica, Crna Gora Tel: +382 20 404 101; Fax: +382 20 665 315 Web site: www.fzocg.me UVOD Fond za zdravstveno osiguranje Crne Gore, shodno Zakonu o zdravstvenom osiguranju, vrši javna ovlašćenja u rješavanju o pravima i obavezama iz obaveznog zdravstvenog osiguranja. Fond ima svojstvo pravnog lica, sa pravima, obavezama i odgovornostima utvrđenim Zakonom i Statutom. Ovom odredbom zakonodavac je Fondu dao određenu samostalnost i autonomiju u izvršavanju tih javnih ovlašćenja. Organi upravljanja Fondom su Upravni odbor i direktor. Poslovi koje obavlja Fond su sljedeći: Sprovodi zdravstveno osiguranje, u skladu sa zakonom; Učestvuje u sprovođenju zdravstvene politike u vezi sa obaveznim zdravstvenim osiguranjem; U vršenju ovih poslova sarađuje se sa Ministarstvom zdravlja i Vladom Crne Gore, kao i drugim organima i institucijama koje su nadležne i imaju odgovornost za obezbjeđivanje i stvaranje uslova za ostvarivanje zdravstvenog osiguranja. Obavlja poslove u vezi sa ostvarivanjem prava osiguranih lica, brine o zakonitom ostvarivanju tih prava i pruža potrebnu pomoć u ostvarivanju prava i zaštitu njihovih interesa; U okviru obavljanja ovih poslova propisuje postupke i načine ostavarivanja prava osiguranih lica u vezi ostvarivanja zdravstvene zaštite, prava na naknadu zarade za vrijeme privremene spriječenosti za rad, prava na putne troškove i dr. Kroz ova akta obezbjeđuje i ostvarivanje prava i zaštitu interesa osiguranih lica. Vodi evidenciju o ostvarenim pravima osiguranih lica iz obaveznog zdravstvenog osiguranja; Za realizaciju tih zakonskih ovlašćenja u Fondu je uspostavljena obimna evidencija o korišćenju zdravstvenih usluga i drugih prava iz zdravstvenog osiguranja. -

The Montenegrin Political Landscape: the End of Political Stability? by Milena Milosevic, Podgorica-Based Journalist Dr

ELIAMEP Briefing Notes 27 /2012 July 2012 The Montenegrin political landscape: The end of political stability? by Milena Milosevic, Podgorica-based journalist Dr. Ioannis Armakolas, “Stavros Costopoulos” Research Fellow, ELIAMEP, Greece The recent start of accession negotiations between the European Commission and Montenegro came against the background of the ever perplexing politics in this Western Balkan country. The minor coalition partner in the ruling government – the Social Democratic Party (SDP) - announced the possibility that it will run in the elections independently from the Democratic Party of Socialists (DPS), the successor of the Communist Party and the party of former Montenegrin leader Milo Djukanovic. SDP and DPS have been in coalition in the national government continuously since 1998. In contast, opposition parties are traditionally perceived as weak and incapable of convincing voters that they can provide a genuine alternative to DPS-led governments. However, at the beginning of July, news of two opposition parties trying to unite all anti-government forces, with the help of the country’s former foreign minister Miodrag Lekic, once again heated up the debate over the opposition’s strength. At about the same time, news concerning the formation of new parties have also dominated the headlines in the local press. Most of the attention is on “Positive Montenegro“, a newly-formed party whose name essentially illustrates its platform: positive change in the society burdened by past mistakes and divisions. The ambivalent context within which the contours of the current Montenegrin political landscape are being drawn further complicates this puzzle. On one hand, the country’s foreign policy and relations with its neigbours are continuously praised by the international community.