Fifty Years of Sino-Italian Bilateral Relations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

October 22, 1962 Amintore Fanfani Diaries (Excepts)

Digital Archive digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org International History Declassified October 22, 1962 Amintore Fanfani Diaries (excepts) Citation: “Amintore Fanfani Diaries (excepts),” October 22, 1962, History and Public Policy Program Digital Archive, Italian Senate Historical Archives [the Archivio Storico del Senato della Repubblica]. Translated by Leopoldo Nuti. http://digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org/document/115421 Summary: The few excerpts about Cuba are a good example of the importance of the diaries: not only do they make clear Fanfani’s sense of danger and his willingness to search for a peaceful solution of the crisis, but the bits about his exchanges with Vice-Minister of Foreign Affairs Carlo Russo, with the Italian Ambassador in London Pietro Quaroni, or with the USSR Presidium member Frol Kozlov, help frame the Italian position during the crisis in a broader context. Credits: This document was made possible with support from the Leon Levy Foundation. Original Language: Italian Contents: English Translation The Amintore Fanfani Diaries 22 October Tonight at 20:45 [US Ambassador Frederick Reinhardt] delivers me a letter in which [US President] Kennedy announces that he must act with an embargo of strategic weapons against Cuba because he is threatened by missile bases. And he sends me two of the four parts of the speech which he will deliver at midnight [Rome time; 7 pm Washington time]. I reply to the ambassador wondering whether they may be falling into a trap which will have possible repercussions in Berlin and elsewhere. Nonetheless, caught by surprise, I decide to reply formally tomorrow. I immediately called [President of the Republic Antonio] Segni in Sassari and [Foreign Minister Attilio] Piccioni in Brussels recommending prudence and peace for tomorrow’s EEC [European Economic Community] meeting. -

Atti Parlamentari Della Biblioteca "Giovarmi Spadolini" Del Senato L'8 Ottobre

SENATO DELLA REPUBBLICA XVII LEGISLATURA Doc. C LXXII n. 1 RELAZI ONE SULLE ATTIVITA` SVOLTE DAGLI ENTI A CARATTERE INTERNAZIONALISTICO SOTTOPOSTI ALLA VIGILANZA DEL MINISTERO DEGLI AFFARI ESTERI (Anno 2012) (Articolo 3, quarto comma, della legge 28 dicembre 1982, n. 948) Presentata dal Ministro degli affari esteri (BONINO) Comunicata alla Presidenza il 16 settembre 2013 PAGINA BIANCA Camera dei Deputati —3— Senato della Repubblica XVII LEGISLATURA — DISEGNI DI LEGGE E RELAZIONI — DOCUMENTI INDICE Premessa ................................................................................... Pag. 5 1. Considerazioni d’insieme ................................................... » 6 1.1. Attività degli enti ......................................................... » 7 1.2. Collaborazione fra enti ............................................... » 10 1.3. Entità dei contributi statali ....................................... » 10 1.4. Risorse degli Enti e incidenza dei contributi ordinari statali sui bilanci ......................................................... » 11 1.5. Esercizio della funzione di vigilanza ....................... » 11 2. Contributi ............................................................................ » 13 2.1. Contributi ordinari (articolo 1) ................................. » 13 2.2. Contributi straordinari (articolo 2) .......................... » 15 2.3. Serie storica 2006-2012 dei contributi agli Enti internazionalistici beneficiari della legge n. 948 del 1982 .............................................................................. -

Quaderni D'italianistica : Revue Officielle De La Société Canadienne

ANGELO PRINCIPE CENTRING THE PERIPHERY. PRELIMINARY NOTES ON THE ITALLVN CANADL\N PRESS: 1950-1990 The Radical Press From the end of the Second World War to the 1980s, eleven Italian Canadian radical periodicals were published: seven left-wing and four right- wing, all but one in Toronto.' The left-wing publications were: II lavoratore (the Worker), La parola (the Word), La carota (the Carrot), Forze nuove (New Forces), Avanti! Canada (Forward! Canada), Lotta unitaria (United Struggle), and Nuovo mondo (New World). The right-wing newspapers were: Rivolta ideale (Ideal Revolt), Tradizione (Tradition), // faro (the Lighthouse or Beacon), and Occidente (the West or Western civilization). Reading these newspapers today, one gets the impression that they were written in a remote era. The socio-political reality that generated these publications has been radically altered on both sides of the ocean. As a con- sequence of the recent disintegration of the communist system, which ended over seventy years of East/West confrontational tension, in Italy the party system to which these newspapers refer no longer exists. Parties bear- ing new names and advancing new policies have replaced the older ones, marking what is now considered the passage from the first to the second Republic- As a result, the articles on, or about, Italian politics published ^ I would like to thank several people who helped in different ways with this paper. Namely: Nivo Angelone, Roberto Bandiera, Damiano Berlingieri, Domenico Capotorto, Mario Ciccoritti, Elio Costa, Celestino De luliis, Odoardo Di Santo, Franca lacovetta, Teresa Manduca, Severino Martelluzzi, Roberto Perin, Concetta V. Principe, Guido Pugliese, Olga Zorzi Pugliese, and Gabriele Scardellato. -

Esercitati GRATIS On-Line! N

N. Domanda A B C D 885 DA CHI ERA COMPOSTO IL SERRISTORI, RICASOLI, PERUZZI, GUERRAZZI, LAMBRUSCHINI, GOVERNO PROVVISORIO RIDOLFI, CAPPONI PUCCIONI MONTANELLI, GIORGINI, MORDINI TOSCANO PROCLAMATO L'8 MAZZONI FEBBRAIO 1849 IN SEGUITO ALLA FUGA DA FIRENZE DI LEOPOLDO II? 886 NEL MARZO 1849, DURANTE LA A NOVARA A MONCALIERI A MAGENTA A CUSTOZA SECONDA FASE DELLA PRIMA GUERRA DI INDIPENDENZA, IN QUALE LOCALITA' LE TRUPPE DEL REGNO DI SARDEGNA FURONO SCONFITTE DALLE TRUPPE AUSTRIACHE? 887 IN QUALE LOCALITA' VITTORIO A VIGNALE A VILLAFRANCA A CUSTOZA A NOVARA EMANUELE II ACCETTO' LE CONDIZIONI ARMISTIZIALI DEL FELDMARESCIALLO RADETZKY? 888 QUALE TRA I SEGUENTI FRANCESCO CARLO PISACANE SILVIO PELLICO DANIELE MANIN PERSONAGGI PRESE PARTE ALLA DOMENICO DIFESA DI ROMA NEL 1849? GUERRAZZI 889 IN SEGUITO ALLA RESA DELLA PORTARE AIUTO PORTARE AIUTO AL ATTACCARE I ASSEDIARE PIO IX REPUBBLICA ROMANA, CON ALLA DIFESA DI GOVERNO FRANCESI A A GAETA QUALE OBIETTIVO GARIBALDI, VENEZIA PROVVISORIO CIVITAVECCHIA INSIEME A 4000 UOMINI, LASCIO' TOSCANO ROMA? 890 CHI E' L'AUTORE DELL'OPUSCOLO GIUSEPPE GIUSEPPE GIUSTI GIUSEPPE FERRARI GIUSEPPE MAZZINI "LA FEDERAZIONE MONTANELLI REPUBBLICANA", PUBBLICATO A CAPOLAGO NEL 1851? 891 QUALI POTENZE INTERRUPPERO SPAGNA E PRUSSIA E RUSSIA E IMPERO FRANCIA E LE RELAZIONI DIPLOMATICHE CON PORTOGALLO AUSTRIA OTTOMANO INGHILTERRA IL REGNO DELLE DUE SICILIE NEL 1856? 892 QUALE DIPLOMATICO SABAUDO EMILIO VISCONTI LUIIG AMEDEO COSTANTINO LUIGI PRINETTI COLLABORO' IN MODO DECISIVO VENOSTA MELEGARI NIGRA CON CAVOUR NELLE TRATTATIVE -

Italy's Atlanticism Between Foreign and Internal

UNISCI Discussion Papers, Nº 25 (January / Enero 2011) ISSN 1696-2206 ITALY’S ATLANTICISM BETWEEN FOREIGN AND INTERNAL POLITICS Massimo de Leonardis 1 Catholic University of the Sacred Heart Abstract: In spite of being a defeated country in the Second World War, Italy was a founding member of the Atlantic Alliance, because the USA highly valued her strategic importance and wished to assure her political stability. After 1955, Italy tried to advocate the Alliance’s role in the Near East and in Mediterranean Africa. The Suez crisis offered Italy the opportunity to forge closer ties with Washington at the same time appearing progressive and friendly to the Arabs in the Mediterranean, where she tried to be a protagonist vis a vis the so called neo- Atlanticism. This link with Washington was also instrumental to neutralize General De Gaulle’s ambitions of an Anglo-French-American directorate. The main issues of Italy’s Atlantic policy in the first years of “centre-left” coalitions, between 1962 and 1968, were the removal of the Jupiter missiles from Italy as a result of the Cuban missile crisis, French policy towards NATO and the EEC, Multilateral [nuclear] Force [MLF] and the revision of the Alliance’ strategy from “massive retaliation” to “flexible response”. On all these issues the Italian government was consonant with the United States. After the period of the late Sixties and Seventies when political instability, terrorism and high inflation undermined the Italian role in international relations, the decision in 1979 to accept the Euromissiles was a landmark in the history of Italian participation to NATO. -

Capitolo Primo La Formazione Di Bettino Craxi

CAPITOLO PRIMO LA FORMAZIONE DI BETTINO CRAXI 1. LA FAMIGLIA Bettino, all’anagrafe Benedetto Craxi nasce a Milano, alle 5 di mattina, il 24 febbraio 1934, presso la clinica ostetrica Macedonio Melloni; primo di tre figli del padre Vittorio Craxi, avvocato siciliano trasferitosi nel capoluogo lombardo e di Maria Ferrari, originaria di Sant’Angelo Lodigiano. 1 L’avvocato Vittorio è una persona preparata nell’ambito professionale ed ispirato a forti ideali antifascisti. Vittorio Craxi è emigrato da San Fratello in provincia di Messina a causa delle sue convinzioni socialiste. Trasferitosi nella città settentrionale, lascia nella sua terra una lunga tradizione genealogica, cui anche Bettino Craxi farà riferimento. La madre, Maria Ferrari, figlia di fittavoli del paese lodigiano è una persona sensibile, altruista, ma parimenti ferma, autorevole e determinata nei principi.2 Compiuti sei anni, Bettino Craxi è iscritto al collegio arcivescovile “De Amicis” di Cantù presso Como. Il biografo Giancarlo Galli narra di un episodio in cui Bettino Craxi è designato come capo classe, in qualità di lettore, per augurare il benvenuto all’arcivescovo di Milano, cardinal Ildefonso Schuster, in visita pastorale. 3 La presenza come allievo al De Amicis è certificata da un documento custodito presso la Fondazione Craxi. Gli ex alunni di quella scuola, il 31 ottobre 1975 elaborano uno statuto valido come apertura di cooperativa. Il resoconto sarà a lui indirizzato ed ufficialmente consegnato il 10 ottobre 1986, allor quando ritornerà all’istituto in veste di Presidente del Consiglio; in quell’occasione ricorderà la sua esperienza durante gli anni scolastici e commemorerà l’educatore laico e socialista a cui la scuola è dedicata. -

Rivista Di "Diritto E Pratica Tributaria"

ISSN 0012-3447 LUGLIO - AGOSTO PUBBLICAZIONE BIMESTRALE Vol. LXXXV - N. 4 FONDATORE ANTONIO UCKMAR DIRETTORE VICTOR UCKMAR UNIVERSITÀ DI GENOVA DIRETTORE SCIENTIFICO CESARE GLENDI UNIVERSITÀ DI PARMA COMITATO DI DIREZIONE ANDREA AMATUCCI MASSIMO BASILAVECCHIA PIERA FILIPPI UNIVERSITÀ FEDERICO II DI NAPOLI UNIVERSITÀ DI TERAMO UNIVERSITÀ DI BOLOGNA GUGLIELMO FRANSONI FRANCO GALLO ANTONIO LOVISOLO UNIVERSITÀ DI FOGGIA UNIVERSITÀ LUISS DI ROMA UNIVERSITÀ DI GENOVA CORRADO MAGNANI GIANNI MARONGIU GIUSEPPE MELIS UNIVERSITÀ DI GENOVA UNIVERSITÀDIGENOVA UNIVERSITÀ LUISS DI ROMA SEBASTIANO MAURIZIO MESSINA LIVIA SALVINI DARIO STEVANATO UVNIVERSITÀ DI ERONA UNIVERSITÀ LUISS DI ROMA UNIVERSITÀ DI TRIESTE www.edicolaprofessionale.com/DPT Tariffa R.O.C.: Poste Italiane S.p.a. - Spedizione in abbonamento postale - D.L. 353/2003 (conv. in L. 27/02/2004 n. 46) art. 1, comma 1, DCB Milano REDAZIONE Direttore e coordinatore della redazione: Antonio Lovisolo. Capo redazione: Fabio Graziano. Comitato di redazione: P. de’ Capitani, F. Capello, G. Corasaniti, C. Corrado Oliva, F. Menti, L.G. Mottura, A. Piccardo, P. Piciocchi, M. Procopio, A. Quattrocchi, N. Raggi, P. Stizza, R. Succio, A. Uricchio, S. Zagà. Segretaria di redazione: Marila Muscolo. Hanno collaborato nel 2014: F. Amatucci, A. Baldassarre, F. Capello, S. Carrea, F. Cerioni, M. Ciarleglio, A. Comelli, A. Contrino, G. Corasaniti, E. Core, S. Dalla Bontà, A. Elia, F. Gallo, G. Giangrande, A. Giovannini, F. Graziano, A. Kostner, I. Lanteri, A. Lovisolo, A. Marcheselli, A. Marinello, G. Marino, G. Marongiu, G. Melis, F. Menti, C. Mione, R. Mistrangelo, M. Procopio, P. Puri, F. Rasi, A. Renda, G. Rocco, S.M. Ronco, G. Salanitro, C. Sallustio, M.V. -

KEY QUESTIONS the Big Six

Italy Donor Profile KEY QUESTIONS the big six Who are the main actors in Italian development cooperation? The MAECI leads on strategy; Italy’s new develop- from other ministries, including Finance and Environ- ment agency, AICS, implements ment. The Joint Development Cooperation Commit- tee (Comitato Congiunto) decides on operational is- The Italian Prime Minister engages in development when sues, including on funding for projects over €2 million it comes to high-level commitments or international con- (US$2.2 million). It is chaired by the MAECI and com- ferences. Giuseppe Conte (no party affiliation) is Prime posed of the heads of MAECI’s DGCS and the develop- Minister of Italy since June 2018. The new government, ment agency AICS. which is based on an usual coalition of the anti-estab- lishment 5-Star Movement and the right-wing League, The Italian Agency for Development Cooperation may shift strategic priorities in development policy. (AICS) was set up in January 2016. It is in charge of devel- Many key positions are still vacant due to the still ongo- oping, supervising, and directly implementing pro- ing government formation, including the Prime Minis- grams. The agency may only autonomously approve pro- ter’s Diplomatic Advisor and the Director of the Italian ject funds of up to €2 million (US$2.2 million). Its staff Agency for Development Cooperation (AICS). number is limited by law to 200. Italian civil society or- ganizations (CSOs) are concerned that the human re- The 2014 law on cooperation profoundly restructured It- source constraint could limit the agency’s capacity to aly’s development cooperation system: It strongly aligns implement the planned increase in development pro- development policy with foreign affairs. -

Renzo Zaffanella Su Pietro Nenni

IL PROFILO UMANO E POLITICO DI NENNI NEL RICORDO DI RENZO ZAFFANELLA* Intervistato da Agostino Melega** Questa volta sono io a chiamare al telefono Zaffanella:<<Renzo, mi potresti rilasciare un’intervista su Pietro Nenni, per l’inserto de L’Eco del popolo su Cronaca?>> <<Volentieri! >>, mi risponde subito pronto, ed il giorno dopo lo raggiungo nella sua abitazione. Trovo l’ex sindaco di Cremona molto disponibile e sereno nel recuperare il filo della memoria sulla figura di Pietro Nenni, del quale il 1° di gennaio di quest’anno è ricorso il trentennale della scomparsa. Il mio interlocutore ha preparato per l’occasione una serie di appunti e di date precise, che hanno contrassegnato, con la vita di Nenni, le vicende politiche del nostro Paese e non solo, e subito confida: <<In una sola cosa non sono stato d’accordo con Nenni: nell’insistere nel rapporto d’alleanza fra il Psiup – si chiamava così il Partito socialista nel 1946 -, ossia fra il Partito socialista italiano di unità proletaria e i comunisti. Nenni non fu certo il solo a portare avanti quel dissanguamento. Fra il 1945 e il 1946 erano infatti molti, fra i socialisti, quelli che spingevano per arrivare a fondere addirittura insieme i due partiti socialista e comunista. E così si portò avanti un’alleanza, quella del Fronte Democratico Popolare, che da una parte impoverì a dismisura la nostra rappresentanza parlamentare e politica, dall’altra ebbe l’effetto di vederci cacciar fuori dall’Internazionale socialista. Nenni, romagnolo generoso, era un passionale, e non si accorse del gioco tattico e del freddo cinismo di Togliatti che tagliava erba nel campo del nostro elettorato, e lo faceva con una determinazione scientifica>>. -

European Public Opinion and Migration: Achieving Common Progressive Narratives

EUROPEAN PUBLIC OPINION AND MIGRATION: ACHIEVING COMMON PROGRESSIVE NARRATIVES Tamás BOROS Marco FUNK Hedwig GIUSTO Oliver GRUBER Sarah KYAMBI Hervé LE BRAS Lisa PELLING Timo RINKE Thilo SCHOLLE EUROPEAN PUBLIC OPINION AND MIGRATION: ACHIEVING COMMON PROGRESSIVE NARRATIVES ACHIEVING EUROPEAN PUBLIC OPINION AND MIGRATION: Luigi TROIANI EUROPEAN PUBLIC OPINION AND MIGRATION: ACHIEVING COMMON PROGRESSIVE NARRATIVES Published by: FEPS – Foundation for European Progressive Studies Rue Montoyer 40 - 1000 Brussels, Belgium T: +32 2 234 69 00 Email: [email protected] Website: www.feps-europe.eu Friedrich Ebert Stiftung Budapest Regional Project „Flight, Migration, Integration in Europe” Fővám tér 2-3 - H-1056 Budapest, Hungary Email: [email protected] Website: www.fes.de/en/displacement-migration-integration/ Friedrich Ebert Stiftung EU Office Brussels Rue du Taciturne 38 - 1000 Brussels, Belgium Email: [email protected] Website: www.fes-europe.eu Fondazione Pietro Nenni Via Caroncini 19 - 00197 Rome, Italy T: +39 06 80 77 486 Email: [email protected] Website: www.fondazionenenni.it Fondation Jean Jaurès 12 cité Malesherbes - 75 009 Paris, France T: +33 1 40 23 24 00 Website: https://jean-jaures.org/ Copyright © 2019 by FEPS, Friedrich Ebert Stiftung, Fondazione Pietro Nenni, Fondation Jean Jaurès Edited by: Marco Funk, Hedwig Giusto, Timo Rinke, Olaf Bruns English language editor: Nicole Robinson This study was produced with the financial support of the European Parliament Cover picture : Shutterstock Book layout: Triptyque.be This study does not represent the collective views of FEPS, Friedrich Ebert Stiftung, Fondazione Pietro Nenni or Fondation Jean Jaurès, but only the opinion of the respective author. The respon- sibility of FEPS, Friedrich Ebert Stiftung, Fondazione Pietro Nenni and Fondation Jean Jaurès is limited to approving its publication as worthy of consideration for the global progressive movement. -

PERFIJ.,ES Pietro N Enni Y Giuseppe Saragat

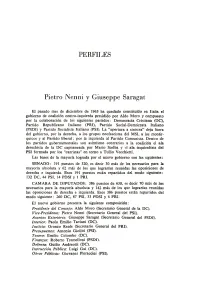

PERFIJ.,ES Pietro N enni y Giuseppe Saragat El pasado mes de diciembre de 1963 ha quedado constituído en Italia el gobierno de coalición centro-izquierda presidido por Aldo Moro y compuesto por la colaboración de los siguientes partidos: Democracia Cristiana (DC), Partido Republicano Italiano (PRI), Partido Social-Demócrata Italiano (PSDI) y Partido Socialista Italiano (PSI). La "apertura a sinistra" deja fuera del gobierno, por la derecha, a los grupos neofascistas del MSI, a los monár quicos y al Partido liberal; por la izquierda al Partido Comunista. Dentro de los partidos gubernamentales son asimismo contrarios a la coalición el ala derechista de la DC capitaneada por Mario Scelba y el ala izquierdista del PSI formada por los "carristas" en tomo a Tullio Vecchietti. Las bases de la mayoría lograda por el nuevo gobierno son las siguientes: SENADO: 191 puestos de 320, es decir 30 más de los necesarios para la mayoría absoluta y 62 más de los que lograrían reunidas las oposiciones de derecha e izquierda. Esos 191 puestos están repartidos del modo siguiente: 132 DC, 44 PSI, 14 PDSI y 1 PRI. CAMARA DE DIPUTADOS: 386 puestos de 630, es decir 70 más de los necesarios para la mayoría absoluta y 142 más de los que lograrían reunidas las oposiciones de derecha e izquierda. Esos 386 puestos están repartidos del modo siguiente: 260 DC, 87 PSI, 33 PDSI y 6 PRI. El nuevo gobierno presenta la siguiente composición: Presidente del Consejo: Aldo Moro (Secretario General de la DC). Vice-Presidente: Pietro Nenni (Secretario General del PSI). Asuntos Exteriores: Giuseppe Saragat (Secretario General del PSDI). -

Governo Conte

Il Governo Conte Documento di analisi e approfondimento dei componenti del nuovo esecutivo Composizione del Governo Conte • Prof. Avv. Giuseppe Conte, Presidente del Consiglio dei Ministri • Dep. Luigi Di Maio. Vicepresidente del Consiglio dei Ministri e Ministro dello Sviluppo Economico, del Lavoro e delle Politiche Sociali • Sen. Matteo Salvini, Vicepresidente del Consiglio dei Ministri e Ministro dell’Interno • Dep. Riccardo Fraccaro, Ministro per i Rapporti con il Parlamento e la Democrazia Diretta • Sen. Avv. Giulia Bongiorno, Ministro per la Pubblica Amministrazione • Sen. Avv. Erika Stefani, Ministro per gli Affari Regionali e le Autonomie • Sen. Barbara Lezzi, Ministro per il Sud • Dep. Lorenzo Fontana, Ministro per la Famiglia e la Disabilità • Prof. Paolo Savona, Ministro per gli Affari Europei • Prof. Enzo Moavero Milanesi, Ministro degli Affari Esteri e della Cooperazione Internazionale • Dep. Avv. Alfonso Bonafede, Ministro della Giustizia • Dott.ssa Elisabetta Trenta, Ministro della Difesa • Prof. Giovanni Tria, Ministro dell’Economia e delle Finanze • Sen. Gian Marco Centinaio, Ministro delle Politiche Agricole, Alimentari e Forestali • Gen. Sergio Costa, Ministro dell’Ambiente e della Tutela del Territorio e del Mare • Sen. Danilo Toninelli, Ministro delle Infrastrutture e dei Trasporti • Dott. Marco Bussetti, Ministro dell’Istruzione, dell’Università e della Ricerca • Dott. Alberto Bonisoli, Ministro dei Beni e delle Attività Culturali e del Turismo • Dep. Giulia Grillo, Ministro della Salute • Dep. Giancarlo Giorgetti, Sottosegretario alla Presidenza del Consiglio dei Ministri con funzione di Segretario dei Consiglio dei Ministri 2 Presidente del Consiglio dei Ministri Giuseppe Conte Nato a Volturara Appula (Foggia) nel 1964, avvocato civilista e professore universitario. Laurea in giurisprudenza conseguita presso l'università «La Sapienza» di Roma (1988).