Annotated Bibliography of New Netherland Archeology In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

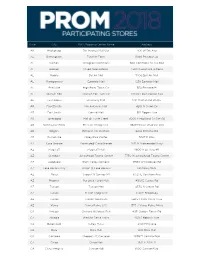

Prom 2018 Event Store List 1.17.18

State City Mall/Shopping Center Name Address AK Anchorage 5th Avenue Mall-Sur 406 W 5th Ave AL Birmingham Tutwiler Farm 5060 Pinnacle Sq AL Dothan Wiregrass Commons 900 Commons Dr Ste 900 AL Hoover Riverchase Galleria 2300 Riverchase Galleria AL Mobile Bel Air Mall 3400 Bell Air Mall AL Montgomery Eastdale Mall 1236 Eastdale Mall AL Prattville High Point Town Ctr 550 Pinnacle Pl AL Spanish Fort Spanish Fort Twn Ctr 22500 Town Center Ave AL Tuscaloosa University Mall 1701 Macfarland Blvd E AR Fayetteville Nw Arkansas Mall 4201 N Shiloh Dr AR Fort Smith Central Mall 5111 Rogers Ave AR Jonesboro Mall @ Turtle Creek 3000 E Highland Dr Ste 516 AR North Little Rock Mc Cain Shopg Cntr 3929 Mccain Blvd Ste 500 AR Rogers Pinnacle Hlls Promde 2202 Bellview Rd AR Russellville Valley Park Center 3057 E Main AZ Casa Grande Promnde@ Casa Grande 1041 N Promenade Pkwy AZ Flagstaff Flagstaff Mall 4600 N Us Hwy 89 AZ Glendale Arrowhead Towne Center 7750 W Arrowhead Towne Center AZ Goodyear Palm Valley Cornerst 13333 W Mcdowell Rd AZ Lake Havasu City Shops @ Lake Havasu 5651 Hwy 95 N AZ Mesa Superst'N Springs Ml 6525 E Southern Ave AZ Phoenix Paradise Valley Mall 4510 E Cactus Rd AZ Tucson Tucson Mall 4530 N Oracle Rd AZ Tucson El Con Shpg Cntr 3501 E Broadway AZ Tucson Tucson Spectrum 5265 S Calle Santa Cruz AZ Yuma Yuma Palms S/C 1375 S Yuma Palms Pkwy CA Antioch Orchard @Slatten Rch 4951 Slatten Ranch Rd CA Arcadia Westfld Santa Anita 400 S Baldwin Ave CA Bakersfield Valley Plaza 2501 Ming Ave CA Brea Brea Mall 400 Brea Mall CA Carlsbad Shoppes At Carlsbad -

"Smackdown on the Hudson" the Patroon, the West India Company, and the Founding of Albany

"Smackdown on the Hudson" The Patroon, the West India Company, and the Founding of Albany Lesson Procedures Essential question: How was the colony of New Netherland ruled by the Dutch West India Company and the patroons? Grade 7 Content Understandings, New York State Standards: Social Studies Standards This lesson covers European Exploration and Colonization of the Americas and Life in Colonial Communities, focusing on settlement patterns and political life in New Netherland. By studying the conflict between the Petrus Stuyvesant and the Brant van Slichtenhorst, students will consider the sources of historic documents and evaluate their reliability. Common Core Standards: Reading Standards By analyzing historic documents, students will develop essential reading, writing, and critical thinking skills. They will read and analyze informational texts and draw inferences from those texts. Students will explain what happened and why based on information from the readings. Additionally, as a class, students will discuss general academic and domain- specific words or phrases relevant to the unit. Speaking and Listening Standards Students will engage in group and teacher-led collaborative discussions, using textual evidence to pose hypotheses and respond to specific questions. They will also report to the class on their group’s assigned topic, explaining their ideas, analyses, and observations and citing reasons and evidence to support their claims. New Netherland Institute New Netherland Research Center "Smackdown on the Hudson" 2 Writing Standards To conclude this lesson, students write a letter to the editor of the Rensselaerwijck Times that draws evidence from informational texts and supports claims with clear reasons and relevant evidence. Historical Context: In 1614, soon after the founding of the New Netherland Company (predecessor to the West India Company, est. -

Fort Orange Garden Club Records, 1923-2007, MG

MG 237 Page 1 A Guide to the Fort Orange Garden Club Records Collection Summary Collection Title: Fort Orange Garden Club Records Call Number: MG 237 Creator: Fort Orange Garden Club Inclusive Dates: 1923-2007 Bulk Dates: Abstract: Contains material regarding the Fort Orange Garden Club such as minutes and reports from meetings, genealogies, general histories, personal histories, membership lists, projects, flower shows, public works, newspaper articles, awards, magazines, scrapbooks, maps, memorabilia, photographs, and slides. Quantity: 21 boxes (Boxes 1-12 files, 13-15 photos, 16 slim file, 17-19 slides, 20 & 21 oversized) Administrative Information Custodial History: Preferred Citation: Fort Orange Garden Club Records Albany Institute of History & Art Library, New York. Acquisition Information: Accession #: Accession Date: Processing Information: Processed by Daniel M. Hart; completed on November 23, 2013 Restrictions Restrictions on Access: None MG 237 Page 2 Restrictions on Use: Permission to publish material must be obtained in writing prior to publication from the Chief Librarian & Archivist, Albany Institute of History & Art, 125 Washington Avenue, Albany, NY 12210. Index Term Persons Becker, John A., Mrs. (see Thompson, Lenden, Joanne Martha, Ms.) Lehman, Orin Beebe, Richard T., Mrs. (Jean) Mahar, Edward F., Mrs. (Christie) Bourdillon, Jacques, Mrs. (Margaret) McKinney, Laurence, Mrs. (Alice) Corning, Betty Meserve, Kathleen K. Corning II, Erastus, Mrs. (Elizabeth Platt Mosher, John Fayette, Mrs. (Helen) Corning) Oberting, Suzanne Crary, Grace Palmer, Edward DeLancy, Mrs. Crummey, Edward J., Mrs. (Betty) (Melissa) Darling, A. Graeme, Mrs. (Marie) Pruyn, Robert C., Mrs. (Anna) DeGraff, John T., Mrs. (Harriett) Reynolds, Nancy Devitt, Robert, Mrs. (Carol) Rockwell, Richard C., Mrs. (Marge) Douglas, Richard A., Mrs. -

Journal of the Holland Society of New York Fall 2015 the Holland Society of New York

de Halve Maen Journal of The Holland Society of New York Fall 2015 The Holland Society of New York GIFT ITEMS for Sale www.hollandsociety.org “Beggars' Medal,” worn by William of Orange at the time of his assassination and adopted by The Holland Society of New York on March 30, 1887 as its official badge The medal is available in: Sterling Silver 14 Carat Gold $2,800.00 Please allow 6 weeks for delivery - image is actual size 100% Silk “Necktie” $85.00 “Self-tie Bowtie” $75.00 “Child's Pre-tied Bowtie” $45.00 “Lapel Pin” Designed to be worn as evidence of continuing pride in membership. The metal lapel pin depicts the Lion of Holland in red enamel upon a golden field. Extremely popular with members since 189 when adoped by the society. $45.00 Make checks payable to: The Holland Society of New York “Rosette” and mail to: 20 West 44th Street, Silk moiré lapel pin in orange, a New York, NY 10036 color long associated with the Dutch $25.00 Or visit our website and pay with Prices include shipping The Holland Society of New York 20 WEST 44TH STREET, NEW YORK, NY 10036 de Halve Maen President Magazine of the Dutch Colonial Period in America Robert R. Schenck Treasurer Secretary VOL. LXXXVIII Fall 2015 NUMBER 3 John G. Nevius R. Dean Vanderwarker III Domine IN THIS ISSUE: Rev. Paul D. Lent Advisory Council of Past Presidents 46 Editor’s Corner Roland H. Bogardus Kenneth L. Demarest Jr. Colin G. Lazier Rev. Louis O. Springsteen Peter Van Dyke W. -

Kings Highway Barrens # K

Barrens Kings Highway Pine Bush Preserve Albany Green Trail – 2.1 miles –2.1 Trail Green miles –1.2 Red Trail adjacent tothispartofthepreserve. linked AlbanyandSchenectadyislocated beyond. ThehistoricKingsHighwaythat stateand habitattypeinNewYork a rare high quality pine barrens vernal ponds, severalsmallbut trailare east ofthered Well native prairiesfoundinthisregion. aswellthe invasive blacklocustforests native pitchpine-oak andhighly forests A looptrailallowsvisitorstoenjoyboth Kings Barrens Highway Trailhead #9 Trailhead Photo by Kirstin Russell This gently rolling sand-plain is home to a unique variety of rare plants and animals including the federally endangered Karner plants and animalsincludingthefederallyendangered bluebutterfly. sand-plainishometoauniquevarietyofrare This gentlyrolling intheworld. examplesofaninlandpinebarrens The AlbanyPineBushisoneofthebestremaining totheAlbanyPineBushPreserve Welcome Great Blue Heron # # # # # # # # little # 0.96# # brown bat # # 81 # # # # # # # # # # Kings Rd # # 80 # # # # # # # # # # # # # three way # sedge # # # # 82 # # # # # hognose snake # # D# # # # # 9 # # 0.24 # Kings Highway # # 84 # # # Barrens # # # # # D 83 k k k k k Curry Rd Ex k k t Gilmore k Te fisher r k k k k k 85 r k Te Ryan Pl k N Dennis k k k k k 86 W E k k k S k k LEGEND k Rifle Range Rd k Albany Pine Bush Trails k Red k k 1.18 big bluestem k Green k k Indian grass k k & Trailhead 87 k k Trail Segment Distances (miles) k k Numbered Trail Locations k Interstate Highway 90 k k Other Roads k k 88 Railroads k Kings Rd Power Lines k I 90 Albany Pine Bush Lands k k Wetlands Oak eeTr Ln k Lakes, Ponds k 5 Foot Contours k k E Old State Rd k Kings Ct Truax Trail 89 k k Barrens k E k k Ly dius St k k k 12 D k k k k k k k k. -

A-Brief-History-Of-The-Mohican-Nation

wig d r r ksc i i caln sr v a ar ; ny s' k , a u A Evict t:k A Mitfsorgo 4 oiwcan V 5to cLk rid;Mc-u n,5 3 ss l Y gew y » w a. 3 k lz x OWE u, 9g z ca , Z 1 9 A J i NEI x i c x Rat 44MMA Y t6 manY 1 YryS y Y s 4 INK S W6 a r sue`+ r1i 3 My personal thanks gc'lo thc, f'al ca ° iaag, t(")mcilal a r of the Stockbridge-IMtarasee historical C;orrunittee for their comments and suggestions to iatataraare tlac=laistcatic: aal aac c aracy of this brief' history of our people ta°a Raa la€' t "din as for her c<arefaal editing of this text to Jeff vcic.'of, the rlohican ?'yews, otar nation s newspaper 0 to Chad Miller c d tlac" Land Resource aM anaagenient Office for preparing the map Dorothy Davids, Chair Stockbridge -Munsee Historical Committee Tke Muk-con-oLke-ne- rfie People of the Waters that Are Never Still have a rich and illustrious history which has been retrained through oral tradition and the written word, Our many moves frorn the East to Wisconsin left Many Trails to retrace in search of our history. Maanv'rrails is air original design created and designed by Edwin Martin, a Mohican Indian, symbol- izing endurance, strength and hope. From a long suffering proud and deternuned people. e' aw rtaftv f h s is an aatathCutic basket painting by Stockbridge Mohican/ basket weavers. -

Risk Assessment: Asset Identification & Characterization

This Working Draft Submittal is a preliminary draft document and is not to be used as the basis for final design, construction or remedial action, or as a basis for major capital decisions. Please be advised that this document and associated deliverables have not undergone internal reviews by URS. SECTION 3b - RISK ASSESSMENT: ASSET IDENTIFICATION & CHARACTERIZATION SECTION 3b - RISK ASSESSMENT: IDENTIFICATION AND CHARACTERIZATION OF ASSETS Overview An inventory of geo-referenced assets in Rensselaer County has been created in order to identify and characterize property and persons potentially at risk from the identified hazards. Understanding the type and number of hazards that exist in relation to known hazard areas is an important step in the process of formulating the risk assessment and quantifying the vulnerability of the municipalities that make up Rensselaer County. For this plan, six key categories of assets have been mapped and analyzed using GIS data provided by Rensselaer County, with some additional data drawn from other public sources: 1. Improved property: This category includes all developed properties according to parcel data provided by Rensselaer County and equalization rates from the New York State Office of Real Property Services. Impacts to improved properties are presented as a percentage of each community’s total value of improvements that may be exposed to the identified hazards. 2. Emergency facilities: This category covers all facilities dedicated to the management and response of emergency or disaster situations, and includes emergency operations centers (EOCs), fire stations, police stations, ambulance stations, shelters, and hospitals. Impacts to these assets are presented by tabulating the number of each type of facility present in areas that may be exposed to the identified hazards. -

Beads from the Hudson's Bay Company's Principal Depot, York Factory, Manitoba, Canada

BEADS: Journal of the Society of Bead Researchers Volume 25 Volume 25 (2013) Article 6 1-1-2013 Beads from the Hudson's Bay Company's Principal Depot, York Factory, Manitoba, Canada Karlis Karklins Gary F. Adams Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/beads Part of the Archaeological Anthropology Commons, History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons, Science and Technology Studies Commons, and the Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons Repository Citation Karklins, Karlis and Adams, Gary F. (2013). "Beads from the Hudson's Bay Company's Principal Depot, York Factory, Manitoba, Canada." BEADS: Journal of the Society of Bead Researchers 25: 72-100. Available at: https://surface.syr.edu/beads/vol25/iss1/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in BEADS: Journal of the Society of Bead Researchers by an authorized editor of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BEADS FROM THE HUDSON’S BAY COMPANY’S PRINCIPAL DEPOT, YORK FACTORY, MANITOBA, CANADA Karlis Karklins and Gary F. Adams There is no other North American fur trade establishment whose half a dozen times in two separate international conflicts. longevity and historical significance can rival that of York Factory. It witnessed a naval engagement and suffered three direct Located in northern Manitoba, Canada, at the base of Hudson Bay, attacks. The factory was rebuilt seven times and was the it was the Hudson’s Bay Company’s principal Bay-side trading base of operations for such fur trade personalities as Pierre post and depot for over 250 years. -

Dutch Influences on Law and Governance in New York

DUTCH INFLUENCES 12/12/2018 10:05 AM ARTICLES DUTCH INFLUENCES ON LAW AND GOVERNANCE IN NEW YORK *Albert Rosenblatt When we talk about Dutch influences on New York we might begin with a threshold question: What brought the Dutch here and how did those beginnings transform a wilderness into the greatest commercial center in the world? It began with spices and beaver skins. This is not about what kind of seasoning goes into a great soup, or about European wearing apparel. But spices and beaver hats are a good starting point when we consider how and why settlers came to New York—or more accurately—New Netherland and New Amsterdam.1 They came, about four hundred years ago, and it was the Dutch who brought European culture here.2 I would like to spend some time on these origins and their influence upon us in law and culture. In the 17th century, several European powers, among them England, Spain, and the Netherlands, were competing for commercial markets, including the far-east.3 From New York’s perspective, the pivotal event was Henry Hudson’s voyage, when he sailed from Holland on the Halve Maen, and eventually encountered the river that now bears his name.4 Hudson did not plan to come here.5 He was hired by the Dutch * Hon. Albert Rosenblatt, former Judge of the New York Court of Appeals, is currently teaching at NYU School of Law. 1 See COREY SANDLER, HENRY HUDSON: DREAMS AND OBSESSION 18–19 (2007); ADRIAEN VAN DER DONCK, A DESCRIPTION OF NEW NETHERLAND 140 (Charles T. -

Pinebush Transportation Study Update

Pinebush Transportation Study Update September 2004 SUMMARY The Albany County Department of Public Works submitted a proposal under CDTC's 2000-01 Community and Transportation Linkage Planning Program requesting that CDTC staff update the 1985 Pinebush Area Transportation Study to "address all of the changes which have occurred since the completion of the Pinebush Area Transportation Study in 1990." The county's proposal indicated that the study would be used to develop a consensus and gain support of all the municipalities and interested parties in the area. The county's proposal was approved and $20,000 was programmed for the study. To accomplish the goals of the linkage study, CDTC staff looked at the transportation system in the Pinebush Study area and identified physical changes that took place over the fifteen-year period, such as intersection configuration, bicycle/pedestrian accommodation, physical condition, etc. To evaluate how the current transportation system is performing, CDTC staff first compared current traffic counts with the 1985 counts and determined where growth, if any occurred. Next, CDTC staff identified the locations where traffic growth exceeded the background growth rate for Albany County and identified any attendant development that occurred that could explain the increase in traffic growth. CDTC staff looked at capacity and level-of-service (LOS) issues at all the locations where current counts were taken. Threshold analysis was conducted at all the intersections and links where current counts were available. Intersection level of service analysis using HCM was conducted at those intersections where current traffic counts and signal timing plans are available. Speed-delay runs were conducted along three major corridors in the study area--New Karner Road, Washington Avenue Extension and Western Avenue. -

Episodes from a Hudson River Town Peak of the Catskills, Ulster County’S 4,200-Foot Slide Mountain, May Have Poked up out of the Frozen Terrain

1 Prehistoric Times Our Landscape and First People The countryside along the Hudson River and throughout Greene County always has been a lure for settlers and speculators. Newcomers and longtime residents find the waterway, its tributaries, the Catskills, and our hills and valleys a primary reason for living and enjoying life here. New Baltimore and its surroundings were formed and massaged by the dynamic forces of nature, the result of ongoing geologic events over millions of years.1 The most prominent geographic features in the region came into being during what geologists called the Paleozoic era, nearly 550 million years ago. It was a time when continents collided and parted, causing upheavals that pushed vast land masses into hills and mountains and complementing lowlands. The Kalkberg, the spiny ridge running through New Baltimore, is named for one of the rock layers formed in ancient times. Immense seas covered much of New York and served as collect- ing pools for sediments that consolidated into today’s rock formations. The only animals around were simple forms of jellyfish, sponges, and arthropods with their characteristic jointed legs and exoskeletons, like grasshoppers and beetles. The next integral formation event happened 1.6 million years ago during the Pleistocene epoch when the Laurentide ice mass developed in Canada. This continental glacier grew unyieldingly, expanding south- ward and retreating several times, radically altering the landscape time and again as it traveled. Greene County was buried. Only the highest 5 © 2011 State University of New York Press, Albany 6 / Episodes from a Hudson River Town peak of the Catskills, Ulster County’s 4,200-foot Slide Mountain, may have poked up out of the frozen terrain. -

New York Genealogical and Biographical Record, Vol 21

K<^' ^ V*^'\^^^ '\'*'^^*/ \'^^-\^^^'^ V' ar* ^ ^^» "w^^^O^o a • <L^ (r> ***^^^>^^* '^ "h. ' ^./ ^^0^ Digitized by the internet Archive > ,/- in 2008 with funding from ' A^' ^^ *: '^^'& : The Library of Congress r^ .-?,'^ httpy/www.archive.org/details/pewyorkgepealog21 newy THE NEW YORK Genealogical\nd Biographical Record. DEVOTED TO THE INTERESTS OF AMERICAN GENEALOGY AND BIOGRAPHY. ISSUED QUARTERLY. VOLUME XXL, 1890. 868; PUBLISHED BY THE SOCIETY, Berkeley Lyceuim, No. 23 West 44TH Street, NEW YORK CITY. 4125 PUBLICATION COMMITTEE: Rev. BEVERLEY R. BETTS, Chairman. Dr. SAMUEL S. PURPLE.. Gen. JAS. GRANT WILSON. Mr. THOS. G. EVANS. Mr. EDWARD F. DE LANCEY. Mr. WILLL\M P. ROBINSON. Press of J. J. Little & Co., Astor Place, New York. INDEX OF SUBJECTS. Albany and New York Records, 170. Baird, Charles W., Sketch of, 147. Bidwell, Marshal] S., Memoir of, i. Brookhaven Epitaphs, 63. Cleveland, Edmund J. Captain Alexander Forbes and his Descendants, 159. Crispell Family, 83. De Lancey, Edward F. Memoir of Marshall S. Bidwell, i. De Witt Family, 185. Dyckman Burial Ground, 81. Edsall, Thomas H. Inscriptions from the Dyckman Burial Ground, 81. Evans, Thomas G. The Crispell Family, 83. The De Witt Family, 185. Fernow, Berlhold. Albany and New York Records, 170 Fishkill and its Ancient Church, 52. Forbes, Alexander, 159. Heermans Family, 58. Herbert and Morgan Records, 40. Hoes, R. R. The Negro Plot of 1712, 162. Hopkins, Woolsey R Two Old New York Houses, 168. Inscriptions from Morgan Manor, N. J. , 112. John Hart, the Signer, 36. John Patterson, by William Henry Lee, 99. Jones, William Alfred. The East in New York, 43. Kelby, William.