Participate in the Atmosphere. Distribution of Involvements and Attachments As Urban Construction Olivier Ocquidant

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Soixante-Quatre Mots De La Ville Le Trésor Des Mots De La Ville

CSU UMR CNRS 7112 59/61 rue Pouchet 75017 Paris France Soixante-quatre mots de la ville Le Trésor des mots de la ville : une maquette au 1/5e février 2005 Le Trésor des mots de la ville : une maquette au 1/5e Sommaire Avertissement 3 Les notices 4 Dictionnaires de langue et encyclopédies 238 Index des entrées par langue 251 Index des auteurs 253 Liste alphabétique des entrées 255 2 Le Trésor des mots de la ville : une maquette au 1/5e Avertissement Cette simulation ou modèle réduit du Trésor des mots de la ville comprend huits entrées sur 40 (environ) pour chacune des huits langues étudiées. C’est donc une maquette au 1/5e. Les notices sont données par ordre alphabétique général (après translittération de l’entrée pour l’arabe et le russe), comme ce sera le cas dans l’ouvrage. Aucun critère thématique n’a présidé au choix des notices présentées ici. > Dans cette maquette, les translittérations qui font appel à des signes diacritiques inhabituels n’apparaissent pas correctement. Il en est de même du nom de l’entrée donné en caractères arabes ou cyrilliques. Chaque notice est précédée – D’une spécification géographique. Il s’agit de l’aire pour laquelle le mot est traité dans la notice, non d’une aire où il serait exclusivement en usage. – D’une ou plusieurs citations de document donnant des solutions de traduction du mot vers le français (exceptionnellement vers l’anglais). – D’une ou plusieurs citations de documents donnant des définitions du mot dans la langue originale (et ici traduites en français). -

Bodacc Bulletin Officiel Des Annonces Civiles Et Commerciales Annexé Au

o Quarante-troisième année. – N 195 B ISSN 0298-2978 Vendredi 9 octobre 2009 BODACCBULLETIN OFFICIEL DES ANNONCES CIVILES ET COMMERCIALES ANNEXÉ AU JOURNAL OFFICIEL DE LA RÉPUBLIQUE FRANÇAISE Standard......................................... 01-40-58-75-00 DIRECTION DES JOURNAUX OFFICIELS Annonces....................................... 01-40-58-77-56 Renseignements documentaires 01-40-58-79-79 26, rue Desaix, 75727 PARIS CEDEX 15 Abonnements................................. 01-40-58-79-20 www.journal-officiel.gouv.fr (8h30à 12h30) www.bodacc.fr Télécopie........................................ 01-40-58-77-57 BODACC “B” Modifications diverses - Radiations Avis aux lecteurs Les autres catégories d’insertions sont publiées dans deux autres éditions séparées selon la répartition suivante Ventes et cessions .......................................... Créations d’établissements ............................ @ Procédures collectives .................................... ! BODACC “A” Procédures de rétablissement personnel .... Avis relatifs aux successions ......................... * Avis de dépôt des comptes des sociétés .... BODACC “C” Banque de données BODACC servie par les sociétés : Altares-D&B, EDD, Extelia, Questel, Tessi Informatique, Jurismedia, Pouey International, Scores et Décisions, Les Echos, Creditsafe, Coface services, Cartegie, La Base Marketing, Infolegale, France Telecom Orange et Telino. Conformément à l’article 4 de l’arrêté du 17 mai 1984 relatif à la constitution et à la commercialisation d’une banque de données télématique des informations contenues dans le BODACC, le droit d’accès prévu par la loi no 78-17 du 6 janvier 1978 s’exerce auprès de la Direction des Journaux officiels. Le numéro : 2,50 € Abonnement. − Un an (arrêté du 21 novembre 2008 publié au Journal officiel du 27 novembre 2008) : France : 367,70 €. Pour l’expédition par voie aérienne (outre-mer) ou pour l’étranger : paiement d’un supplément modulé selon la zone de destination ; tarif sur demande Paiement à réception de facture. -

Making a New World David and the Revolution

Making a New World David and the Revolution 'Never was any such event so inevitable yet so completely unforeseen', was how the great historian Alexis de Tocqueville characterized the coming of the French Revolution. From a distance of more than two hundred years, we can see that the Revolution was the result of a series of social, economic and political pressures which, though manageable in themselves, had the cumulative effect of toppling the monarchy and chang- ing the course of French and European history. By the mid-1780s the whole framework of the ancien regime seemed close to breakdown. As a legacy of its expensive involvement in the American War of Independence (1778-83), 70 Let's Hope that France was facing bankruptcy and the government was forced this Game Ends Soon, to borrow more and more money to cover its deficits. The 1789 . Coloured public was also aware of how the lavish and extravagant engraving ; 36-5 - 24cm, expenditure of the court added to the nation's debts, and they 141e" 9 1 zin were outraged at the waste. Tensions also existed between the aristocracy and the emerging middle classes, with the latter group trying hard to gain social acceptance and a rise in their influence and status . Of course these issues of politics and class were of little importance to the poor, the vast majority of whom lived in degradation and misery trying to scratch a living from the land. They laid the blame for their misfortunes squarely at the feet of the Church and the aristocracy which claimed crip- pling tithes and feudal dues (70). -

George Condo

GEORGE CONDO Bibliographie / Bibliography Bücher und Kataloge / Books and catalogs 2019 ‘George Condo. Life is worth Living‘, Almine Rech Editions 2018 ‘George Condo at Cycladic’, Museum of Cycladic Art, Athens 2016 Kittelmann, Udo / Rappe, Felicia: ‘Condo: Confrontation‘, Museum Berggruen, Nationalgalerie, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Berlin Kehlmann, Daniel: ‘Gesichter, Fratzen, Condo‘, Museum Berggruen, Nationalgalerie, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Berlin 2015 Baker, Simon: ‘George Condo: Painting Reconfigured’, London: Thames and Hudson Ltd. 2014 ‘George Condo: Ink Drawings’, London: Skarstedt. 2013 ‘George Condo. Paintings Sculpture’, Berlin: Distanz Verlag. 2012 Rugoff, Ralph / Hollein, Max: ‘George Condo Mental States’, München: Prestel Verlag. 2011 Rugoff, Ralph: ‘George Condo: Mental States’, Manchester: Hayward Publishing. 2010 Troncy, Eric: ‘Cartoon Abstractions’, Paris: Galerie Jerome de Noirmont. Berckemeyer, Olivia / Wurlitzer, Bernd: ‘Physical’, Berlin: Kunsthaller Autocenter. 2009 Lorguin, Olivier / Lorguin, Bertrand: ‘George Condo: La civilisation perdue, édition bilingue français-anglais’, Paris: Fondation Dina Vierny-Musée Maillol / Editions Gallimard. Kellein, Thomas: ‘George Condo’, Brussels: Xavier Hufkens. Haendel, Karl: ‘Beg borrow and steal’, Miami: Rubell Family Collection. 2008 ‘George Condo: Artificial Realism’, Moskow: Gary Tatintsian Gallery Inc. 2007 Caruso, Laura (ed.): ‘Radar: Selections from the Collection of Vicki and Kent Logan’, Denver: Denver Art Museum, pp. 76-79. ‘Create your own Museum: Highlights from a Private Collection’, Moscow: Gary Tantintsian Gallery Inc., pp. 38-43. ‘Impulse: Works on Paper from the Logan Collection’, Vail, Colorado: The Logan Collection, pp. 8-9, 22, 36, 38. Jacobs, Dan: ‘Negotiating Reality: Recent Works from the Logan Collection’, Denver: University of Denver, pp. 24-25, 68. Kirwin, Liza / Moore, Alan W. : ‘East Village USA’, New Museum of Contemporary Art, 8 November, p. -

THEODORE JONES, Alias TED JOANS

THEODORE JONES, alias TED JOANS JAZZ POET, MUSICIAN, PAINTER and CARTOONIST 4th July 1928 – 25 th April 2003 The phrase Jazz is my religion and surrealism is my point of view written by Ted Joans resumes him well, but we shall see that these are not his only artistic dimensions. Passing away two months before his 75 th birthday Ted Joans had lived several lives: • He was born in 1928 on American Independence Day, on a boat where his father was an entertainer, and had lived in several towns, notably New York during 10 years, between 1951 and 1960. • He exiled himself to Europe , particularly to Paris where he resided for quite some time. • In parallel he travelled in Africa , his point of attachement being Mali where he kept a house at Timbuktu , more or less up to his death. • He also travelled punctually in Central America , and Mexico was not unknown to him. • He died in Canada . Teenager his first emotions as a young reader were surrealist , then upon his arrival in France he wrote to André Breton , who opened wide the doors to his movement. Previously Ted Joans had also invested in the Beat movement: amongst others he knew Jack Kerouac in New York and he frequented the famous Beat Hotel , situated at 9, rue Gît-le Cœur in Paris with William Burroughs and Allen Ginsberg . In music Ted Joans was rarely mistaken, he admired and knew (some very closely) all the greatest jazzmen, from Louis Armstrong to Albert Ayler , Duke Ellington to John Coltrane , Charlie Parker to Archie Shepp , in passing Charlie Mingus . -

Curriculum Vitae

DAWN-MICHELLE BAUDE Writer, Editor, World Traveler [email protected] Education — Ph.D. in English, University of Illinois - Chicago, IL, 2004 Emphasis: History of Rhetoric, Postmodern Poetry, Modern American Poetry, 20th-Century American Nonfiction — D.E.A. (Diplôme des Etudes Approfondis) in English, Université de Paris-Sorbonne (Paris IV) - Paris, France, 1997 Emphasis: Shakespearean Prosody — M.F.A. in Creative Writing, Mills College - Oakland, CA, 1989 Emphasis: Fiction, Shakespeare — M.A. in Poetics, New College of California - San Francisco, CA, 1986 Emphasis: Literary Theory, Modernism, Postmodernism, Hermeticism — B.A. in English, San Diego State University - San Diego, CA, 1982 Emphasis: Creative Writing Honors, Awards & Recognitions (selected) — Fellow, Jentel Artist Residency - Banner, WY, 2021 For unpublished excerpts from FREEZE FRAME (autofiction) — Associate Artist, Atlantic Center for the Arts - New Smyrna Beach, FL, 2021 For unpublished excerpts from FREEZE FRAME (fiction) — Fellow, PlySpace Residency Program - Muncie, IN, 2020-21 For unpublished excerpts from FREEZE FRAME (autofiction) — Maggie Award Co-Nominee with Kim Foster, Veronica Klash and T.R. Witcher for Best Feature - March 2020 For “Now You See—Just looking isn’t the same as really seeing” personal essay published in the Desert Companion folio, “In the Realm of the Senses” - April 2019 SEE — The FOLIO Award Co-Winner with Kim Foster, Veronica Klash and T.R. Witcher - October 2019 For “Now You See—Just looking isn’t the same as really seeing” personal -

A Historical Materialist Analysis of the Theological Turn of Alain Badiou

Archives of Defeat? A historical materialist analysis of the theological turn of Alain Badiou. Thomas Matthew Rudman A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the Department of English, Manchester Metropolitan University for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy August 2015 1 ABSTRACT This thesis offers a historical materialist analysis of the use of messianic discourses in contemporary theoretical and literary texts. It focuses on the way the recent ‘theological turn’ in Marxist theory relates to two major historical developments: the ascendency of neoliberal capitalism and the perceived absence of any socialist alternative. In theoretical terms, it produces a symptomatic analysis of Alain Badiou and his attempt to re-invigorate communist militancy via the figure of Saint Paul. Rather than follow Badiou’s avowedly atheistic turn to Paul, I undertake a materialist analysis of the texts of early Christianity in order to show that their style of ideological and political subversion is not incompatible with the egalitarian aims of Marxism. I extend this analysis of the radical potentiality of Christian discourses by examining the significance of messianic discourses in contemporary fiction in novels by Eoin McNamee and Roberto Bolaño. Both novelists deploy the conventions of crime fiction to narrate stories of revolutionary disillusionment and the impact of neoliberal economics in the north of Ireland and the Mexico-US border. My analysis focuses on issues of literary form and how the use of messianic imagery produces formal ruptures in the texts which trouble or disturb their manifest ideologies, notably the sense of revolutionary disillusionment and the notion that there is no longer any possibility of radical social change. -

2017 4Th Quarter

The Philatelic Communicator Journal of the American Philatelic Society Writers Unit #30 -30- www.wu30.org Fourth Quarter 2017 Issue 198 In Paris, Passion Battles the Decline of Stamp Collecting The New York Times / By ELAINE SCIOLINO OCT. 18, 2017 Myself, a long time New York Times reader, did not Arrondissement (district) has long been the city’s see this article with my morning tea on October stamp district. There are reportedly about 30 stamp 18th. That story and its section was whisked out of shops that line the Rue Drouot near the Hôtel the house by my dear Drouot, one of the wife as she went to world’s oldest auction work. She does that all houses. the time. Gene Fricks There are also a few sent me a copy. That’s more shops in the the main reason I got to Passage des Panora- read it. The Times would mas in the Second be happy to allow me to Arrondissement as reprint that article but well as a few more the price would be a bit shops in the Eighth high for our small Arrondissement. group. I somewhat fear There used to be even using the photos many more dealers in they published. So I the Carré Marigny, an Parisinfo.com found a couple of simi- open air court that lar photos from Google was donated to the Images that might be city in 1860 to be used safe enough. IFSDA, for stamp dealers. It is the International Feder- still busy on weekends ation of Stamp Dealers but certainly not as Associations, reprinted much as even a few the article at their site decades ago. -

Jumping Electrons by Larry Cheng Ball Game, Gray Began the Lecture, Over Ten Angstroms, a Significant the Flier Read "A Chemist with Slides for Visual Aid

The California Tech I VOLUME LXXXIX NUMBER 27 PASADENA, CALIFORNIA FRIDAY 13 MAY 1988 Jumping Electrons by Larry Cheng ball game, Gray began the lecture, over ten angstroms, a significant The flier read "A Chemist with slides for visual aid. He ex ly long way in terms of molecules, Looks at Electron Transport in Bi plained how chemists were now between different atoms in some ology. Harry B. Gray, PhD." Tick "sneaking up" on the secrets ofhow proteins in a space ofonly one mil ets had been handed out in Chem electron reactions and other reac lionth of a second. 1c lecture that Wednesday morn tions stored energy in living cells. This seems to confirm the the ing by Professor Gray to his fresh "Food," Gray said, "makes ory that "the stupid electron does men students and teaching electrons." jump." In comparison, electrons assistants. Many of them showed Theorists have claimed that could only jump comparable dis up that night. Also in attendance these high energy electrons move tances over water molecules in the were members of the Profs down in energy through an "elec space ofa month. Experiments by research group, and many others tron transport chain" which has yet others in 1984 had even shown even a large number ofhigh school to be fully explained. It is known electrons to jump through steroids students (rumor had it that extra that the same sort ofprocess works in the space of one billionth of a credit was in the air). in such machines as a car engine, second. Harry Gray illustrates the finer points of Electron Jumping in the Watson Those in attendance were treat but for some reason the cellular He explained that steroids had ed to a lecture that was both en process is much more efficient. -

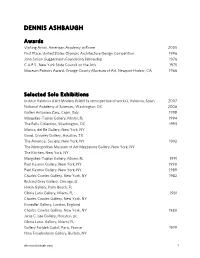

Dennis Ashbaugh Profile

DENNIS ASHBAUGH Awards Visiting Artist, American Academy in Rome 2005 First Place, United States Olympic Architecture Design Competition 1996 John Simon Guggenheim Foundation Fellowship 1976 C.A.P.S., New York State Council on the Arts 1975 Museum Patrons Award, Orange County Museum of Art, Newport Harbor, CA 1966 Selected Solo Exhibitions Institut Valencia d’Art Modern IVAM (a retrospective of works), Valencia, Spain 2007 National Academy of Sciences, Washington, DC 2006 Galleri Antonina Zaru, Capri, Italy 1998 Margulies-Taplan Gallery, Miami, FL 1994 The Ralls Collection, Washington, DC 1993 Marisa, del Re Gallery, New York, NY Good, Crowley Gallery, Houston, TX The Americas Society, New York, NY 1992 The Metropolitan Museum of Art Mezzanine Gallery, New York, NY The Kitchen, New York, NY Margulies-Taplan Gallery, Miami, FL 1991 Paul Kasmin Gallery, New York, NY 1990 Paul Kasmin Gallery, New York, NY 1989 Charles Cowles Gallery, New York, NY 1982 Richard Gray Gallery, Chicago, IL Hokin Gallery, Palm Beach, FL Gloria Luria Gallery, Miami, FL 1981 Charles Cowles Gallery, New York, NY Knoedler Gallery, London, England Charles Cowles Gallery, New York, NY 1980 Janie C. Lee Gallery, Houston, pc Gloria Luria. Gallery, Miami, FL Gallery Farideh Cadot, Paris, France 1979 Nina Freudenheim Gallery, Buffalo, NY dennisashbaugh.com 1 Alexandria Monett Gallery, Brussels, Belgium 1977 PS I, Long Island City, NY Seattle Art Museum, Seattle, WA 1976 Gallery Farideh Cadot, Paris, France Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, NY 1975 Tower Gallery, -

Our New Transmitter Arrives at Mt Lofty

INSIDE > Meet our first Indigenous broadcaster > Why we should all worry about the new terror laws > New SA music on The Piping Shrike Hour > NAIDOC 2006 coverage > Jazz legends and innovators WINTER 2006 PROGRAM GUIDE Our new tra nsmitter arrives a t Mt Lofty see inside for details of when we switch on Radioand Adelaide power Program Guide upWinter 2006 i ii There was a bit of heaving and a lot of ho ho ho at Mount Lofty on May 17, when our new 5 kilowatt transmitter arrived packed in a couple of big boxes. This transmitter was partly funded through the donations of our supporters during our powering up campaign of 2002/03 and is the final part of the upgrade to our FM transmission, following our move We are a community radio station to a new site with larger antenna in owned and operated by The University of Adelaide. 2003. The other half of the money came from a grant form the Federal In Adelaide tune into 101.5 FM Everywhere else streaming in Real Audio Government through the Community at radio.adelaide.edu.au Broadcasting Foundation, which we We provide diverse radio to Adelaide greatly appreciate. and the world with a focus on lifelong learning, arts, ideas, news, local issues, For tech heads it's an RVR 5000 current affairs and good music in many watt solid state FM transmitter with 5 genres. plug in RF power transmitters, plug We have a large and committed team of in power supply, single 30-watt high volunteers and a small core staff. -

PRODUITS DE LA RECHERCHE, 2012 À Juin 2017

CENTRE ANDRÉ CHASTEL – PRODUITS DE LA RECHERCHE, 2012 à juin 2017 Référence En cas de cosignature, sont soulignés les noms des membres du Centre André Chastel. Statut du chercheur N° référence JOURNAUX / REVUES Articles scientifiques Andrieux Jean-Yves, « La grande hauteur. Une architecture incomprise et controversée », Place publique. La revue urbaine, n° 17, Chercheur statutaire 1. mai-juin 2012, p. 6-11 et 42-44. Balcon-Berry Sylvie, « Les figures royales de la cathédrale de Reims », Osterreichische Zeitschrift für Kunst und Denkmalpflege, LXVI, Chercheur statutaire 2. 2012, Heft 3/4, Dynastische Repräsentation in der Glasmalerei, p. 249-259. Banjenec Élise, « Une cour cousue d’or : les ornements précieux utilisés par le duc Philippe le Bon », Questes, bulletin des Jeunes Chercheurs médiévistes, n° 25, avril 2013, numéro L’Habit fait-il le moine ?, p. 45-64. Publication en ligne : Doctorant 3. questes.free.fr/pdf/bulletins/0025/04-art_Elise.pdf. Baudez Basile, « “No es el dibujo lo que constituye arquitecto” : debates sobre la naturaleza de la arquitectura en las academias de Chercheur statutaire 4. París y Madrid en el siglo de las Luces », Cuadernos Dieciochistas, Madrid, vol. 17, 2016, p. 185-238. Baudez Basile, « A Palace for Louis XVI. Jean-Augustin Renard at Rambouillet », Metropolitan Museum Journal, vol. 51, 2016. Chercheur statutaire 5. Baudez Basile, « Le comte d’Angiviller, directeur de travaux. Le cas du domaine de Rambouillet », Livraisons d’histoire de Chercheur statutaire 6. l’architecture, n° 26, 2013, Les Ministres et les arts, p. 13-25. Bazin-Henry Sandra, « Des miroirs peints italiens aux trumeaux de glace à la française : querelle de modèles dans les palais romains Doctorant 7.