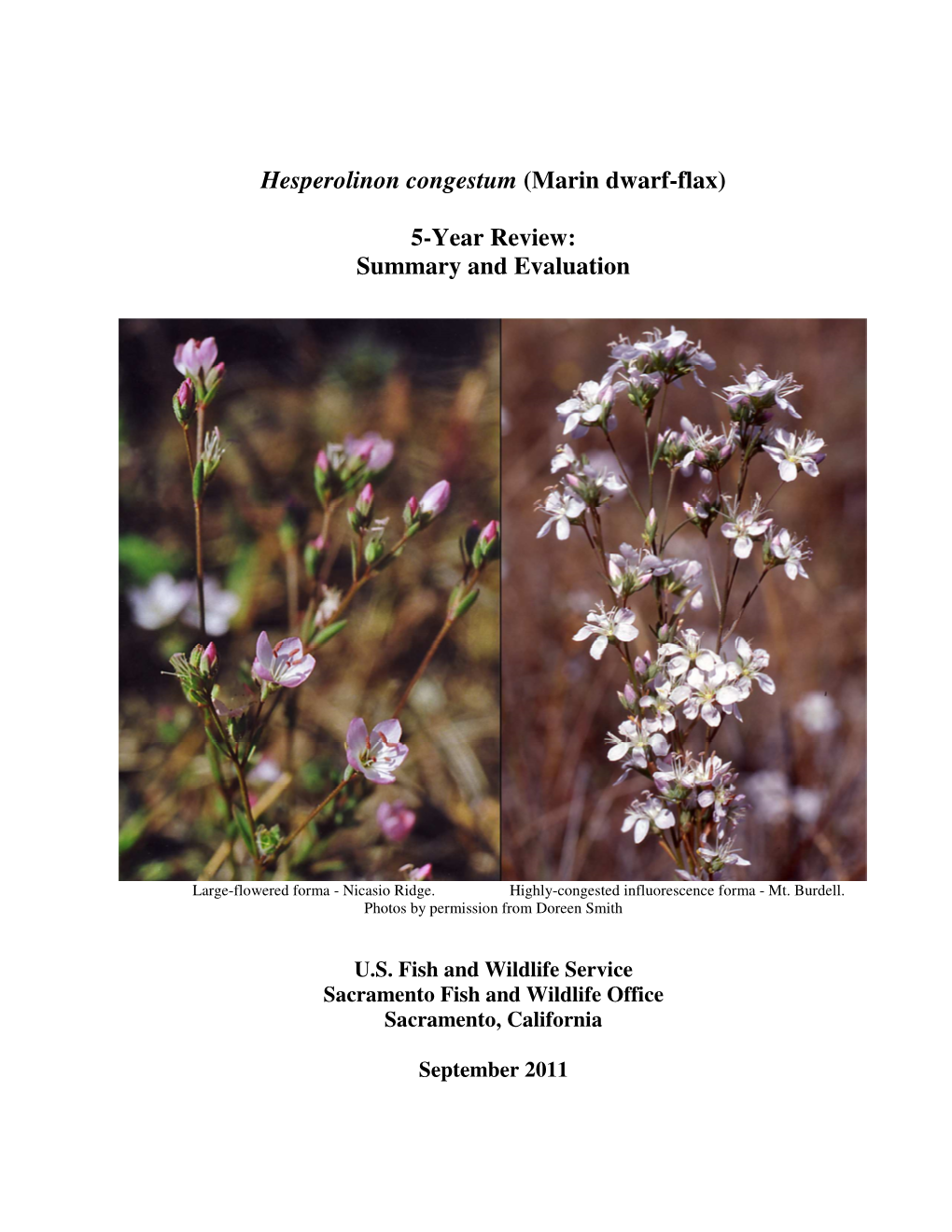

Hesperolinon Congestum (Marin Dwarf-Flax) 5-Year Review: Summary And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pollinator Niche Partitioning and Asymmetric Facilitation Contribute to The

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.03.02.974022; this version posted March 4, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. 1 1 Pollinator niche partitioning and asymmetric facilitation contribute to the 2 maintenance of diversity 3 Na Wei,1,2* Rainee L. Kaczorowski,1 Gerardo Arceo-Gómez,1,3 Elizabeth M. O'Neill,1 Rebecca 4 A. Hayes,1 Tia-Lynn Ashman1* 5 Affiliations: 6 1Department of Biological Sciences, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA, USA. 7 2The Holden Arboretum, Kirtland, OH, USA. 8 3Department of Biological Sciences, East Tennessee State University, Johnson City, TN, USA. 9 *Corresponding authors. Email: [email protected] and [email protected]. 10 Abstract: 11 Mechanisms that favor rare species are key to the maintenance of diversity. One of the most 12 critical tasks for biodiversity conservation is understanding how plant–pollinator mutualisms 13 contribute to the persistence of rare species, yet this remains poorly understood. Using a process- 14 based model that integrates plant–pollinator and interspecific pollen transfer networks with floral 15 functional traits, we show that niche partitioning in pollinator use and asymmetric facilitation 16 confer fitness advantage of rare species in a biodiversity hotspot. While co-flowering species 17 filtered pollinators via floral traits, rare species showed greater pollinator specialization leading 18 to higher pollination-mediated male and female fitness than abundant species. When plants 19 shared pollinator resources, asymmetric facilitation via pollen transport dynamics benefited the 20 rare species at the cost of the abundant ones, serving as an alternative diversity-promoting 21 mechanism. -

FLORA from FĂRĂGĂU AREA (MUREŞ COUNTY) AS POTENTIAL SOURCE of MEDICINAL PLANTS Silvia OROIAN1*, Mihaela SĂMĂRGHIŢAN2

ISSN: 2601 – 6141, ISSN-L: 2601 – 6141 Acta Biologica Marisiensis 2018, 1(1): 60-70 ORIGINAL PAPER FLORA FROM FĂRĂGĂU AREA (MUREŞ COUNTY) AS POTENTIAL SOURCE OF MEDICINAL PLANTS Silvia OROIAN1*, Mihaela SĂMĂRGHIŢAN2 1Department of Pharmaceutical Botany, University of Medicine and Pharmacy of Tîrgu Mureş, Romania 2Mureş County Museum, Department of Natural Sciences, Tîrgu Mureş, Romania *Correspondence: Silvia OROIAN [email protected] Received: 2 July 2018; Accepted: 9 July 2018; Published: 15 July 2018 Abstract The aim of this study was to identify a potential source of medicinal plant from Transylvanian Plain. Also, the paper provides information about the hayfields floral richness, a great scientific value for Romania and Europe. The study of the flora was carried out in several stages: 2005-2008, 2013, 2017-2018. In the studied area, 397 taxa were identified, distributed in 82 families with therapeutic potential, represented by 164 medical taxa, 37 of them being in the European Pharmacopoeia 8.5. The study reveals that most plants contain: volatile oils (13.41%), tannins (12.19%), flavonoids (9.75%), mucilages (8.53%) etc. This plants can be used in the treatment of various human disorders: disorders of the digestive system, respiratory system, skin disorders, muscular and skeletal systems, genitourinary system, in gynaecological disorders, cardiovascular, and central nervous sistem disorders. In the study plants protected by law at European and national level were identified: Echium maculatum, Cephalaria radiata, Crambe tataria, Narcissus poeticus ssp. radiiflorus, Salvia nutans, Iris aphylla, Orchis morio, Orchis tridentata, Adonis vernalis, Dictamnus albus, Hammarbya paludosa etc. Keywords: Fărăgău, medicinal plants, human disease, Mureş County 1. -

Outline of Angiosperm Phylogeny

Outline of angiosperm phylogeny: orders, families, and representative genera with emphasis on Oregon native plants Priscilla Spears December 2013 The following listing gives an introduction to the phylogenetic classification of the flowering plants that has emerged in recent decades, and which is based on nucleic acid sequences as well as morphological and developmental data. This listing emphasizes temperate families of the Northern Hemisphere and is meant as an overview with examples of Oregon native plants. It includes many exotic genera that are grown in Oregon as ornamentals plus other plants of interest worldwide. The genera that are Oregon natives are printed in a blue font. Genera that are exotics are shown in black, however genera in blue may also contain non-native species. Names separated by a slash are alternatives or else the nomenclature is in flux. When several genera have the same common name, the names are separated by commas. The order of the family names is from the linear listing of families in the APG III report. For further information, see the references on the last page. Basal Angiosperms (ANITA grade) Amborellales Amborellaceae, sole family, the earliest branch of flowering plants, a shrub native to New Caledonia – Amborella Nymphaeales Hydatellaceae – aquatics from Australasia, previously classified as a grass Cabombaceae (water shield – Brasenia, fanwort – Cabomba) Nymphaeaceae (water lilies – Nymphaea; pond lilies – Nuphar) Austrobaileyales Schisandraceae (wild sarsaparilla, star vine – Schisandra; Japanese -

Pollen Flora of Pakistan -Lxi. Violaceae

Pak. J. Bot., 41(1): 1-5, 2009. POLLEN FLORA OF PAKISTAN -LXI. VIOLACEAE ANJUM PERVEEN AND MUHAMMAD QAISER* Department of Botany, University of Karachi, Karachi, Pakistan *Federal Urdu University of Arts, Science and Technology, Karachi, Pakistan. Abstract Pollen morphology of 5 species of the family Violaceae from Pakistan has been examined by light and scanning electron microscope. Pollen grains are usually radially symmetrical, isopolar, colporate, sub-prolate to prolate-spheroidal. Sexine slightly thicker or thinner than nexine. Tectum mostly densely punctate rarely psilate. On the basis of exine pattern two distinct pollen types viz., Viola pilosa–type and Viola stocksii-type are recognized. Introduction Violaceae is a family with 20 genera and about 800 species (Mabberley, 1987). In Pakistan it is represented by one genus and 17 species (Qaiser & Omer, 1985). Plant perennial herbs, or shrubs leaves simple, alternate rarely opposite, flowers bisexual, zygomorphic or actinomorphic, calyx 5, corolla of 5 petals, anterior petal large and spurred. Androecium of 5 stamens. Gynoecium a compound pistil of 3 united carpels, ovules superior, fruit capsule. The family is of little economic importance except for the garden favorite, Violets, Violas and Pansies. Pollen morphology of the family has been examined by Erdtman (1952), Lobreau- Callen (1977), Moore & Webb (1978) and Dojas et al., (1993). Moore et al., (1991) examined pollen morphology of the genus Viola. Kubitzki (2004) examined the pollen morphology of the family Violaceae. There are no reports on pollen morphology of the family Violaceae from Pakistan. Present investigations are based on the pollen morphology of 5 species representing a single genus of the family Violaceae by light and scanning electron microscope. -

Evolutionary History of Floral Key Innovations in Angiosperms Elisabeth Reyes

Evolutionary history of floral key innovations in angiosperms Elisabeth Reyes To cite this version: Elisabeth Reyes. Evolutionary history of floral key innovations in angiosperms. Botanics. Université Paris Saclay (COmUE), 2016. English. NNT : 2016SACLS489. tel-01443353 HAL Id: tel-01443353 https://tel.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-01443353 Submitted on 23 Jan 2017 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. NNT : 2016SACLS489 THESE DE DOCTORAT DE L’UNIVERSITE PARIS-SACLAY, préparée à l’Université Paris-Sud ÉCOLE DOCTORALE N° 567 Sciences du Végétal : du Gène à l’Ecosystème Spécialité de Doctorat : Biologie Par Mme Elisabeth Reyes Evolutionary history of floral key innovations in angiosperms Thèse présentée et soutenue à Orsay, le 13 décembre 2016 : Composition du Jury : M. Ronse de Craene, Louis Directeur de recherche aux Jardins Rapporteur Botaniques Royaux d’Édimbourg M. Forest, Félix Directeur de recherche aux Jardins Rapporteur Botaniques Royaux de Kew Mme. Damerval, Catherine Directrice de recherche au Moulon Président du jury M. Lowry, Porter Curateur en chef aux Jardins Examinateur Botaniques du Missouri M. Haevermans, Thomas Maître de conférences au MNHN Examinateur Mme. Nadot, Sophie Professeur à l’Université Paris-Sud Directeur de thèse M. -

Curriculum Vitae Adam Schneider

Curriculum Vitae Adam Schneider Department of Integrative Biology and (608) 445-9083 University and Jepson Herbaria [email protected] University of California – Berkeley 1001 Valley Life Sciences Building Berkeley, CA 94720-2465 Education Ph.D. Candidate, Integrative Biology University of California–Berkeley Major Advisor: Bruce Baldwin Advanced to Candidacy May 2014 B.S. Biology, Chemistry University of Wisconsin–Eau Claire (Summa Cum Laude) 2012 International Student University of Ghana–Legon Spring 2011 Professional Appointments and Fellowships University of California, Berkeley Berkeley Graduate Fellow 2012-present Graduate Student Researcher 2013-2015 Graduate Student Instructor 2013-2015 Taught laboratory, field trips, and guest lectures for: California Plant Life (2 sem.) Medical Ethnobotany (2 sem. + summer) Plant Systematics (1 sem.) Charles Darwin Research Station Herbarium, Galápagos, Ecuador Curatorial Intern May-Aug 2011 University of Wisconsin, Eau Claire Blugold Fellow 2009- 2011 - Planned and executed a study of plant responses to differing water regimes with Dr. Tali Lee. Publications In Review Schneider A.C., W. A. Freyman, C. M. Guilliams, Y. P. Springer, B. G. Baldwin (in review) Pleistocene radiation of the serpentine-adapted genus Hesperolinon and other divergence times in Linaceae (Malpighiales). American Journal of Botany. Kulhanek K.A.*, L.C. Ponicio*, A.C. Schneider*, R. E. Walsh* (in review) Strategic conversation: Mission and relevance of national parks. In Beissinger S.R., D.D. Ackerly, H. Dormus, G. Machelis, Science for parks, parks for science: The next century. University of Chicago Press. Curriculum Vitae Adam Schneider Page 2 Peer-reviewed Publications: 1. Schneider, A.C., T.D. Lee, M.A. Kreiser, G.T. -

Vegetation and Biodiversity Management Plan Pdf

April 2015 VEGETATION AND BIODIVERSITY MANAGEMENT PLAN Marin County Parks Marin County Open Space District VEGETATION AND BIODIVERSITY MANAGEMENT PLAN DRAFT Prepared for: Marin County Parks Marin County Open Space District 3501 Civic Center Drive, Suite 260 San Rafael, CA 94903 (415) 473-6387 [email protected] www.marincountyparks.org Prepared by: May & Associates, Inc. Edited by: Gail Slemmer Alternative formats are available upon request TABLE OF CONTENTS Contents GLOSSARY 1. PROJECT INITIATION ...........................................................................................................1-1 The Need for a Plan..................................................................................................................1-1 Overview of the Marin County Open Space District ..............................................................1-1 The Fundamental Challenge Facing Preserve Managers Today ..........................................1-3 Purposes of the Vegetation and Biodiversity Management Plan .....................................1-5 Existing Guidance ....................................................................................................................1-5 Mission and Operation of the Marin County Open Space District .........................................1-5 Governing and Guidance Documents ...................................................................................1-6 Goals for the Vegetation and Biodiversity Management Program ..................................1-8 Summary of the Planning -

Rigid Flax Linum Medium (Planch.) Britt

Rigid Flax Linum medium (Planch.) Britt. var. texanum (Planch.) Fern State Status: Threatened Federal Status: None Description: Rigid Flax is a perennial herb of the flax family (Linaceae), with yellow five-petaled flowers borne on stiff, ascending branches. Plants grow 2 to 7 dm (~8– 28 in.) in height. The flower petals are 4 to 8 mm long. The styles are distinct (i.e., not united at the base). The sepals are imbricate, and the inner ones have teeth with bulbous glandular tips along their edges. Leaves are entire, lance-shaped, and up to 2.5 cm (1 in.) long with the largest leaves towards the base of the plant. The upper leaves are alternate and usually have pointed tips, while those of the lowest nodes are opposite and blunt tipped. The sepals persist long after the petals have withered and subtend the small (2 mm), dry seed capsules. The species is most often found growing in barren, disturbed areas on sterile soil. Aids to identification: • Plants with stiffly ascending branches • Densely leaved with 30 to 70 leaves below the inflorescence • Lowest leaves opposite; upper leaves alternate • Seed capsules more-or-less spherical with a flattened top • Inner sepals with glandular teeth • Most easily identified when fruit are present Similar species: Four yellow-flowered Linum species that might be mistaken for Rigid Flax occur in Massachusetts. Grooved Yellow Flax (L. sulcatum var. sulcatum) differs from the other three in that it is an annual and its styles are united at the base. Woodland Yellow Flax (L. virginianum) and Panicled Yellow Flax (L. -

Brewer's Dwarf Flax (Hesperolinon Breweri)

Plants Brewer’s Dwarf Flax (Hesperolinon breweri) Brewer’s Dwarf Flax (Hesperolinon breweri) Status Federal: None State: None CNPS: List 1B Population Trend Global: Unknown State: Unknown Within Inventory Area: Unknown Data Characterization The location database for Brewer’s dwarf flax (Hesperolinon breweri) includes 25 data records dated from 1885 to 1997 (California Natural Diversity Database 2001). Only 3 occurrences were documented in the last 10 years, but all occurrences are believed to be extant (California Natural Diversity Database 2001). Fourteen of the occurrences are of high precision and may be accurately located, including 8 occurrences within the inventory area. Very little ecological information is available for Brewer’s dwarf flax. The literature on the species pertains primarily to its taxonomy. The main sources of general information on this species are the Jepson Manual (Hickman 1993) and the California Native Plant Society (2001). Specific observations on habitat and plant associates, threats, and other factors are summarized in the California Natural Diversity Database (2001). Range Brewer’s dwarf flax is endemic to California, where it is restricted to the Mount Diablo and adjacent foothills in the east San Francisco Bay Area and to the Vaca Mountains of the southern interior North Coast Ranges (Hickman 1993, California Natural Diversity Database 2001). It occurs below 2,900 feet above sea level. Occurrences within the ECCC HCP/NCCP Inventory Area Thirteen occurrences of Brewer’s dwarf flax occur within the inventory area. Two of the occurrences are in Mount Diablo State Park, 3 in East Bay Regional Park District lands, and 7 within the Los Vaqueros Watershed. -

Sacramento Fish & Wildlife Office

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Sacramento Fish & Wildlife Office Species Account MARIN DWARF-FLAX Hesperolinon congestum CLASSIFICATION: Threatened Federal Register Notice 60:6671; February 3, 1995 http://ecos.fws.gov/docs/federal_register/fr2779.pdf (125 KB) This species was listed as endangered by the California Department of Fish and Game in June 1992 under the name Marin western flax. The California Native Plant Society has placed it on List 1B (rare or endangered throughout its range), also under the alternate name. CRITICAL HABITAT: Not designated RECOVERY PLAN: Final Recovery Plan for Serpentine Soil Species of the San Francisco Bay Area; September 30, 1998. http://ecos.fws.gov/docs/recovery_plan/980930c_v2.pdf (22 MB) Marin Dwarf-Flax © 1997 Doreen L. Smith 5-YEAR REVIEW: Started March 25, 2009 http://www.fws.gov/policy/library/E8-4258.html DESCRIPTION Marin dwarf-flax, ( Hesperolinon congestum ), also known as Marin western flax, is a herbaceous annual of the flax family (Linaceae). It has slender, threadlike stems, 10-40 cm (4-16 inches) tall. The leaves are linear. Flowers bloom from May to July. They are borne in congested clusters. Pedicels are 1 to 8 mm (0.04 to 3.2 inches) long . Sepals are hairy and the five petals are rose to whitish. Anthers are deep pink to purple. This helps distinguish Marin dwarf-flax from California dwarf-flax ( H. californicum ), found in the same geographic area, which has white to rose anthers, as well as hairless sepals. Two other species that are found in the same region are small- flower dwarf-flax ( H. -

LINACEAE 1. REINWARDTIA Dumortier, Commentat. Bot. 19

LINACEAE 亚麻科 ya ma ke Liu Quanru (刘全儒)1; Lihua Zhou (周丽华)2 Herbs or shrubs. Stipules small or absent. Leaves alternate or rarely opposite, simple; leaf blade margin entire. Inflorescences cymes or racemes. Flowers bisexual, regular. Sepals (4 or)5, distinct or basally connate, imbricate, persistent. Petals as many as and alternate with sepals, distinct or basally connate, convolute, basally often clawed, with 2–5 extrastaminal nectary glands or a disk. Stamens (4 or)5 or 10(or 15), in 1 whorl, alternate or opposite sepals, often some reduced to staminodes; filament bases connate into a tube. Ovary superior, with 2–5 carpels or seemingly 4–10-loculed by intrusion of a false septum, with 1 or 2 ovules per locule, placentation axile; styles as many as carpels, filiform, distinct or basally connate; stigmas subcapitate. Fruit usually a septicidal capsule or a drupe. Seeds with straight oily embryo and thin endosperm. Fourteen genera and ca. 250 species: worldwide but mostly in temperate regions; four genera and 14 species (one introduced) in China. Huang Chengchiu, Huang Baoxian & Xu Langran. 1998. Linaceae. In: Xu Langran & Huang Chengchiu, eds., Fl. Reipubl. Popularis Sin. 43(1): 93–108. 1a. Shrubs or small trees. 2a. Petals yellow; ovary 6(–8)-loculed by intrusion of a false septa; styles 3(or 4); capsule splitting into 6(–8) mericarps ................................................................................................................................................................ 1. Reinwardtia 2b. Petals white; ovary 4- or 5-loculed; styles 4 or 5; capsule 4- or 5-valvate ................................................................. 2. Tirpitzia 1b. Herbs. 3a. Leaves sessile; leaf blade linear to lanceolate, 1- or 3-veined from base; petals usually blue, rarely white or yellow; styles 5; capsule with 10 1-seeded mericarps ................................................................................................................. -

Conceptual Special-Status Plant and Sensitive Habitat Restoration and Revegetation Plan

Conceptual Special-status Plant and Sensitive Habitat Restoration and Revegetation Plan PG&E Gas Transmission Line 109 Farm Hill Blvd Pipeline Replacement Project Pacific Gas & Electric Company Conceptual Special-status Plant and Sensitive Habitat Restoration and Revegetation Plan PG&E Gas Transmission Line 109 Farm Hill Blvd Pipeline Replacement Project Page 1. Conceptual Restoration and Revegetation Plan 1 1.1 Planning, Obtaining Materials, and Site Preparation 4 1.2 Final Grading, Compaction, and Preparation for Restoration 5 1.3 Seeding and Installation of Plant Materials 6 1.4 Post-Installation Maintenance 8 1.5 Restoration of Marin Western Flax 9 2. Restoration Monitoring and Reporting 13 2.1 Photomonitoring 13 2.2 Sampling Herbaceous Cover 13 2.3 Performance Criteria 14 2.5 As-Built and Annual Monitoring Reporting Requirements 15 2.6 Monitoring, Performance Criteria, Reporting and Adaptive Management for Marin Western Flax Restoration Area 15 3. References 18 4. TABLES Table 1 Summary of Restoration Actions, by Restoration Area, PG&E Gas Transmission L 109 Farm Hill Blvd Pipeline Replacement Project 2 Table 2 Seed Mix 1, for Serpentine Bunchgrass Planting Area, PG&E Gas Transmission L 109 Farm Hill Blvd Pipeline Replacement Project 6 Table 3 Seed Mix 2, for Danthonia Prairie Planting Areas, PG&E Gas Transmission L 109 Farm Hill Blvd Pipeline Replacement Project 7 Table 4 Seed Mix 3, for Disturbed Non-native Areas, PG&E Gas Transmission L 109 Farm Hill Blvd Pipeline Replacement Project 7 Table 5 Planting Palette, by Planting Area,