(Yanni the Westerner): an Example of Muslim-Christian Tolerance in Jeddah During the 20Th Century

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

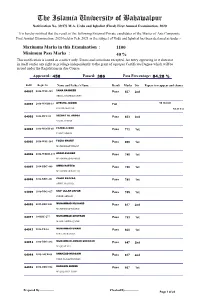

M.A Urdu and Iqbaliat (Final)

The Islamia University of Bahawalpur Notification No. 39/CS M.A. Urdu and Iqbaliat (Final) First Annual Examination, 2020 It is hereby notified that the result of the following External/Private candidates of the Master of Arts Composite First Annual Examination, 2020 held in Feb, 2021 in the subject of Urdu and Iqbaliat has been declared as under:- Maximum Marks in this Examination : 1100 Minimum Pass Marks : 40 % This notification is issued as a notice only. Errors and omissions excepted. An entry appearing in it does not in itself confer any right or privilege independently to the grant of a proper Certificate/Degree which will be issued under the Regulations in due Course. -5E -4E Appeared: 458 Passed: 386 Pass Percentage: 84.28 % Roll# Regd. No Name and Father's Name Result Marks Div Papers to reappear and chance 64001 2016-WST-348 SANA RASHEED Pass 637 2nd ABDUL RASHEED KHAN VII IX X XI 64002 2016-WNDR-19 AYESHA JAVAID Fail JAVAID AKHTAR R/A till S-22 64003 2014-IWY-88 SEERAT UL AROOJ Pass 653 2nd NASIR AHMAD 64004 2016-MOCB-05 FAZEELA BIBI Pass 712 1st JAM GAMMON 64005 2016-WST-164 FOZIA SHARIF Pass 690 1st MUHAMMAD SHARIF 64006 2016-WBDR-173 ANAM ASGHAR Pass 740 1st MUHAMMAD ASGHAR 64007 2018-BDC-440 AMNA RAFEEQ Pass 730 1st MUHAMMAD RAFEEQ 64008 2016-BDC-481 ZAHID RAZZAQ Pass 741 1st ABDUL RAZZAQ 64009 2016-BDC-427 SAIF ULLAH ZAFAR Pass 745 1st ZAFAR AHMAD 64010 2015-BDC-623 MUHAMMAD MUJAHID Pass 617 2nd MUHAMMAD AKRAM 64011 10-BDC-277 MUHAMMAD GHUFRAN Pass 753 1st MALIK ABDUL QADIR 64012 2016-US-16 MUHAMMAD UMAIR Pass 660 1st GHULAM RASOOL 64013 2016-BDC-434 MUHAMMAD AHMAD SHEHZAD Pass 647 2nd LIAQUAT ALI 64014 2015-AICB-08 SHAHZAD HUSSAIN Pass 617 2nd SYED SAJJAD HUSSAIN 64015 2016-BDC-542 HASNAIN AHMED Pass 667 1st MULAZIM HUSSAIN Prepared By--------------- Checked By-------------- Page 1 of 24 Roll# Regd. -

Reforming Madrasa Education in Pakistan; Post 9/11 Perspectives Ms Fatima Sajjad

Volume 3, Issue 1 Journal of Islamic Thought and Civilization Spring 2013 Reforming Madrasa Education in Pakistan; Post 9/11 Perspectives Ms Fatima Sajjad Abstract Pakistani madrasa has remained a subject of intense academic debate since the tragic events of 9/11 as they were immediately identified as one of the prime suspects. The aim of this paper is to examine the post 9/11 academic discourse on the subject of madrasa reform in Pakistan and identify the various themes presented in them. This paper also seeks to explore the missing perspective in this discourse; the perspective of ulama; the madrasa managers, about the Western demand to reform madrasa. This study is based on qualitative research methods. To evaluate the views of academia, this study relies on a systematic analysis of the post 9/11 discourse on this subject. To find out the views of ulama, in-depth interviews of leading Pakistani ulama belonging to all major schools of thought have been conducted. The study finds that many fears generated by early post 9/11 studies were rejected by the later ones. This study also finds that contrary to the common perception the leading ulama in Pakistan are open to the idea of madrasa reform but they prefer to do it internally as an ongoing process and not due to outside pressure. This study recommends that in order to resolve the madrasa problem in Pakistan, it is imperative to take into account the ideas and concerns of ulama running them. It is also important to take them on board in the fight against the religious militancy and terrorism in Pakistan. -

Khawaja and the 'Amazing Bros'

Archived Content Information identified as archived on the Web is for reference, research or record-keeping purposes. It has not been altered or updated after the date of archiving. Web pages that are archived on the Web are not subject to the Government of Canada Web Standards. As per the Communications Policy of the Government of Canada, you can request alternate formats on the "Contact Us" page. Information archivée dans le Web Information archivée dans le Web à des fins de consultation, de recherche ou de tenue de documents. Cette dernière n’a aucunement été modifiée ni mise à jour depuis sa date de mise en archive. Les pages archivées dans le Web ne sont pas assujetties aux normes qui s’appliquent aux sites Web du gouvernement du Canada. Conformément à la Politique de communication du gouvernement du Canada, vous pouvez demander de recevoir cette information dans tout autre format de rechange à la page « Contactez-nous ». CANADIAN FORCES COLLEGE - COLLÈGE DES FORCES CANADIENNES NSP 1 - PSN 1 DIRECTED RESEARCH PROJECT May 18, 2009 KHAWAJA AND THE ‘AMAZING BROS’: A TEST OF CANADA’S ANTI-TERRORISM LAWS AS A RESPONSE TO THE CHALLENGES OF TRANSNATIONAL TERRORISM By/par DEBRA W. ROBINSON This paper was written by a student La présente étude a été rédigée par attending the Canadian Forces un stagiaire du Collège des Forces College in fulfillment of one of the canadiennes pour satisfaire à l’une requirements of the Course of des exigences du cours. L’étude est Studies. The paper is a scholastic un document qui se rapporte au cours document, and thus contains facts et contient donc des faits et des and opinions which the author opinions que seul l’auteur considère alone considered appropriate and appropriés et convenables au sujet. -

1St CABINET UNDER the PREMIERSHIP of SYED YOUSAF RAZA GILLANI, the PRIME MINISTER from 25.03.2008 to 11.02.2011

1st CABINET UNDER THE PREMIERSHIP OF SYED YOUSAF RAZA GILLANI, THE PRIME MINISTER FROM 25.03.2008 to 11.02.2011 S.NO. NAME WITH TENURE PORTFOLIO PERIOD OF PORTFOLIO 1 2 3 4 SYED YOUSAF RAZA GILLANI, PRIME MINSITER, 25.03.2008 to 11.02.2011 FEDERAL MINISTERS 1. Chaudhry Nisar Ali Khan i) Communication and 31.03.2008 to 13.05.2008 Senior Minister ii) Inter Provincial Coordination 08.04.2008 to 13.05.2008 31.03.2008 to 13.05.2008 iii) Food Agriculture & Livestock (Addl. Charge) 31.03.2008 to 13.05.2008 2. Makhdoom Amin Fahim Commerce 04.11.2008 to 11.02.2011 03.11.2008 to 11.02.2011 3. Mr. Shahid Khaqan Abbassi, Commerce 31.03.2008 to 12.05.2008 31.03.2008 to 12.05.2008 4. Dr. Arbab Alamgir Khan Communications 04.11.2008 to 11.02.2011 03.11.2008 to 11.02.2011 5. Khawaja Saad Rafique i) Culture 31.03.2008 to 13.05.2008 31.03.2008 to 13.05.2008 ii) Youth Affairs (Addl. Charge) 31.03.2008 to 13.05.2008 6. Chaudhry Ahmed Mukhtar i) Defence 31.03.2008 to 11.02.2011 31.03.2008 to 11.02.2011 ii) Textile Industry 15.04.2008 to 03.11.2008 iii) Commerce 15.04.2008 to 03.11.2008 7. Rana Tanveer Hussain Defence Production 31.03.2008 to 13.05.2008 31.03.2008 to 13.5.2008 8. Mr. Abdul Qayyum Khan Jatoi Defence Production 04.11.2008 to 03.10.2010 03.11.2008 to 03.10.2010 9. -

SUFIS and THEIR CONTRIBUTION to the CULTURAL LIFF of MEDIEVAL ASSAM in 16-17"' CENTURY Fttasfter of ^Hilojiopl)?

SUFIS AND THEIR CONTRIBUTION TO THE CULTURAL LIFF OF MEDIEVAL ASSAM IN 16-17"' CENTURY '•"^•,. DISSERTATION SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF fttasfter of ^hilojiopl)? ' \ , ^ IN . ,< HISTORY V \ . I V 5: - • BY NAHIDA MUMTAZ ' Under the Supervision of DR. MOHD. PARVEZ CENTRE OF ADVANCED STUDY DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALIGARH (INDIA) 2010 DS4202 JUL 2015 22 CENTRE OF ADVANCED STUDY Department of History Aligarh Muslim University Aligarh-202 002 Dr. Mohd. Parwez Dated: June 9, 2010 Reader To Whom It May Concern This is to certify that the dissertation entitled "Sufis and their Contribution to the Cultural Life of Medieval Assam in 16-17^^ Century" is the original work of Ms. Nahida Muxntaz completed under my supervision. The dissertation is suitable for submission and award of degree of Master of Philosophy in History. (Dr. MoMy Parwez) Supervisor Telephones: (0571) 2703146; Fax No.: (0571) 2703146; Internal: 1480 and 1482 Dedicated To My Parents Acknowledgements I-11 Abbreviations iii Introduction 1-09 CHAPTER-I: Origin and Development of Sufism in India 10 - 31 CHAPTER-II: Sufism in Eastern India 32-45 CHAPTER-in: Assam: Evolution of Polity 46-70 CHAPTER-IV: Sufis in Assam 71-94 CHAPTER-V: Sufis Influence in Assam: 95 -109 Evolution of Composite Culture Conclusion 110-111 Bibliography IV - VlU ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS It is pleasant duty for me to acknowledge the kindness of my teachers and friends from whose help and advice I have benefited. It is a rare obligation to express my gratitude to my supervisor Dr. Mohd. -

Professor James Winston Morris Department of Theology Boston College E-Mail: [email protected] Office Telephone: 617-552-0571 Many of Prof

1 Professor James Winston Morris Department of Theology Boston College e-mail: [email protected] Office telephone: 617-552-0571 Many of Prof. Morris’s articles and reviews, and some older books, are now freely available in searchable and downloadable .pdf format at http://dcollections.bc.edu/james_morris PREVIOUS ACADEMIC POSITIONS: 2006-present Boston College, Professor, Department of Theology. 1999-2006 University of Exeter, Professor, Sharjah Chair of Islamic Studies and Director of Graduate Studies and Research, Institute of Arab and Islamic Studies. 1989-99: Oberlin College: Assoc. Professor, Department of Religion. 1988-89: Temple University: Asst. Professor, Department of Religion. 1987-88: Princeton University: Visiting Professor, Department of Religion and Department of Near Eastern Studies. 1981-87: Institute of Ismaili Studies, Paris/London (joint graduate program in London with McGill University, Institute of Islamic Studies): Professor, Department of Graduate Studies and Research. EDUCATION AND ACADEMIC HONORS: HARVARD UNIVERSITY PH.D, NEAR EASTERN LANGUAGES CAMBRIDGE, MASSACHUSETTS AND CIVILIZATIONS, 1980 Major field: Islamic philosophy and theology; minor fields: classical philosophy, Arabic language and literature, Persian language and literature, . Fellowships: Danforth Graduate Fellowship (1971-1978); Whiting Foundation Dissertation Fellowship (1978-1979); foreign research fellowships (details below). UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO B.A., CIVILIZATIONAL CHICAGO, ILLINOIS STUDIES, 1971 Awards and Fellowships: University Scholar; -

Mapping the Global Muslim Population

MAPPING THE GLOBAL MUSLIM POPULATION A Report on the Size and Distribution of the World’s Muslim Population October 2009 About the Pew Forum on Religion & Public Life This report was produced by the Pew Research Center’s Forum on Religion & Public Life. The Pew Forum delivers timely, impartial information on issues at the intersection of religion and public affairs. The Pew Forum is a nonpartisan, nonadvocacy organization and does not take positions on policy debates. Based in Washington, D.C., the Pew Forum is a project of the Pew Research Center, which is funded by The Pew Charitable Trusts. This report is a collaborative effort based on the input and analysis of the following individuals: Pew Forum on Religion & Public Life Communications and Web Publishing Luis Lugo, Director Erin O’Connell, Associate Director, Communications Oliver Read, Web Manager Research Loralei Coyle, Communications Manager Alan Cooperman, Associate Director, Research Robert Mills, Communications Associate Brian J. Grim, Senior Researcher Liga Plaveniece, Program Coordinator Mehtab S. Karim, Visiting Senior Research Fellow Sahar Chaudhry, Research Analyst Pew Research Center Becky Hsu, Project Consultant Andrew Kohut, President Jacqueline E. Wenger, Research Associate Paul Taylor, Executive Vice President Kimberly McKnight, Megan Pavlischek and Scott Keeter, Director of Survey Research Hilary Ramp, Research Interns Michael Piccorossi, Director of Operations Michael Keegan, Graphics Director Editorial Alicia Parlapiano, Infographics Designer Sandra Stencel, Associate Director, Editorial Russell Heimlich, Web Developer Andrea Useem, Contributing Editor Tracy Miller, Editor Sara Tisdale, Assistant Editor Visit http://pewforum.org/docs/?DocID=450 for the interactive, online presentation of Mapping the Global Muslim Population. -

Genocidal Antisemitism: a Core Ideology of the Muslim Brotherhood Markos Zografos

Genocidal Antisemitism: A Core Ideology of the Muslim Brotherhood Markos Zografos OCCASIONAL PAPER SERIES no. 4/2021 INSTITUTE FOR THE STUDY OF GLOBAL ANTISEMITISM AND POLICY Chair Natan Sharansky Executive Director Charles Asher Small Academic Steering Committee Professor Irving Abella Dr. Ramy Aziz Professor Ellen Cannon Professor Brahm Canzer Professor Raphael Cohen-Almagor Professor Amy Elman Professor Sylvia Barack Fishman Professor Boaz Ganor Dr. Joël Kotek Professor Dan Michman Professor David Patterson Chloe Pinto Dr. Robert Satloff Charles Asher Small (Chair) ISGAP Oxford ◆ New York.◆ Rome ◆ Toronto.◆ Jerusalem www.isgap.org [email protected] The opinions expressed in this paper are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Institute for the Study of Global Antisemitism and Policy, its officers, or the members of its boards. Cover design and layout by AETS © 2021 ISBN 978-1-940186-15-3 ANTISEMITISM IN COMPARATIVE PERSPECTIVE Collected Papers edited by Charles A. Small The Yale Papers The ISGAP Papers, Vol. 2 The ISGAP Papers, Vol. 3 GLOBAL ANTISEMITISM: A CRISIS OF MODERNITY Conference Papers edited by Charles A. Small Volume I: Conceptual Approaches Volume II: The Intellectual Environment Volume III: Global Antisemitism: Past and Present Volume IV: Islamism and the Arab World Volume V: Reflections MONOGRAPHS Industry of Lies: Media, Academia, and the Israeli-Arab Conflict Ben-Dror Yemini The Caliph and the Ayatollah: Our World under Siege Fiamma Nirenstein Putin’s Hybrid War and the Jews: Antisemitism, Propaganda, and the Displacement of Ukrainian Jewry Sam Sokol Antisemitism and Pedagogy: Papers from the ISGAP-Oxford Summer Institute for Curriculum Development in Critical Antisemitism Studies Charles A. -

Khwaja Ghulam Farid - Poems

Classic Poetry Series Khwaja Ghulam Farid - poems - Publication Date: 2012 Publisher: Poemhunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive Khwaja Ghulam Farid(1845-1901) Hazrat Khawaja Ghulam Farid (Urdu, Saraiki: ???? ????? ????? ????, (Gurmukhi): ????? ??????? ?????? ?????, Hindi(Devanagari): ????? ??????? ?????? ?????), Khwaja Ghulam Fareed Sahib or Khawaja Farid is considered one of the greatest Saraiki poets, Chishti-Nizami mystic and Sajjada nashin (Patron saint) of the Punjab region of the Indian subcontinent. He was born and died at Chacharan Shrif but buried at Kot Mithan. He was the son of Khwaja Khuda Bakhsh. His mother died when he was five years old and he was orphaned at age twelve when his father died. He was educated by his elder brother, Fakhr Jahan Uhdi. He was a scholar of that time and wrote several books. He knew Arabic, Persian, Urdu, Sindhi, Panjabi, Braj Bhasha, and Saraiki. He was a poet of Saraiki and Urdu. He also wrote some poems in Sindhi, Persian, and Braj Bhasha. He was an imperialist poet. He opposed British rule in Bahawalpur. He said to ruler of Bahawalpur in his poem, "You rule yourself on your state and finish police station of British from your state." On 168th birthday Urs in 2008, many Saraiki nationists gathered to call for an independent Saraikistan. <b>Themes of Poetry and Teachings</b> His poetry is full of love with Allah, Prophet Muhammad s.a, humanity and nature. He has used the symbolism of desert life of Rohi Cholistan and waseb at most places in his poetry. The beloved's intense glances call for -

Shortlised Candidates for Final Interview of Various Positions

Government of Pakistan Finance Division External Finance Policy Wing ***** The following candidates have been shortlisted for various positions as per detail given below: Energy Sector Specialist Sr. Name of Candidate No 1 Kashif Nadim Rashid ,S/o M.A Rashid Hameed Street, Jan Mohammad Road, Quetta 2 Sajjad Akram S/o M. Akram Chaudhary H.No. 212, Ground Porton, Street. 99, I-8/4 Islamabad 3 Sardar Rahat Azeem, S/o Sardar M. Azeem Khan Suite 10, Block-A, Super Market, F-6, Islamabad 4 Saqib Masood, S/o Muniwar Ahmed IQ-1/104 PARCO Housing Complex Distt. Muzaffargarh 5 M. Mudassar Ali Khan H.No. 4-B, Bashir Street. No. 8, Karamabad Wahdat Road Lahore. Cost Accountant 1 Mr. Muhammad Idress, C/O Muhammad Ghawas Director IT, APPC Headquarter, 18 Muave Area, G- 7/1 Zero Point Islamabad 2 Mr. Salman Shahzad, C-51/1, Block # 4 Gulshan-e- Iqbal Karachi 3 Mr. Waqar Hassan Randhawa, 42-D New Muslim town, Lahore 4 Mr. Muhammad Saleem Akhter, 94/C, Nawab Town, Raiwind Road, Lahore Data Officer 1 Mr. Muhammad Atif Javed, H# 78-G, Saddi Street, New Mangral Model Town P/O Fazaia, Rawalpindi 2 Mr. Raheeb Muzaffar, H# 329, St# 40, G-9/1, Islamabad 3 Mr.Shah Hussain Alvi, Federal EPI Cell, National Institute of Health, Islamabad, 4 Ms. Nimra Zahid, 18-E, St# 58, G-6/4 Islamabad, 5 Mr. Ashraf Ali, Flat # 111, Room# 1, St # 32, I&T Centre G-9/1, Islamabad 6 Mr. Abid Iftikhar, H# 2253, Mian road, Sector I-10/2, Kurang Road, Islamabad 7 Mr. -

Coke Studio Pakistan: an Ode to Eastern Music with a Western Touch

ISSN (Online) - 2349-8846 Coke Studio Pakistan: An Ode to Eastern Music with a Western Touch SHAHWAR KIBRIA Shahwar Kibria ([email protected]) is a research scholar at the School of Arts and Aesthetics at the Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi. Vol. 55, Issue No. 12, 21 Mar, 2020 Since it was first aired in 2008, Coke Studio Pakistan has emerged as an unprecedented musical movement in South Asia. It has revitalised traditional and Eastern classical music of South Asia by incorporating contemporary Western music instrumentation and new-age production elements. Under the religious nationalism of military dictator Muhammad Zia-ul-Haq, the production and dissemination of creative arts were curtailed in Pakistan between 1977 and 1988. Incidentally, the censure against artistic and creative practice also coincided with the transnational movement of qawwali art form as prominent qawwals began carrying it outside Pakistan. American audiences were first exposed to qawwali in 1978 when Gulam Farid Sabri and Maqbool Ahmed Sabri performed at New York’s iconic Carnegie Hall. The performance was referred to as the “aural equivalent of the dancing dervishes” in the New York Times (Rockwell 1979). However, it was not until Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan’s performance at the popular World of Music, Arts and Dance (WOMAD) festival in 1985 in Colchester, England, following his collaboration with Peter Gabriel, that qawwali became evident in the global music cultures. Khan pioneered the fusion of Eastern vocals and Western instrumentation, and such a coming together of different musical elements was witnessed in several albums he worked for subsequently. Some of them include "Mustt Mustt" in 1990 ISSN (Online) - 2349-8846 and "Night Song" in 1996 with Canadian musician Michael Brook, the music score for the film The Last Temptation of Christ (1988) and a soundtrack album for the film Dead Man Walking (1996) with Peter Gabriel, and a collaborative project with Eddie Vedder of the rock band Pearl Jam. -

Sufism and Mysticism in Aurangzeb Alamgir's Era Abstract

Global Social Sciences Review (GSSR) Vol. IV, No. II (Spring 2019) | Pages: 378 – 383 49 Sufism and Mysticism in Aurangzeb Alamgir’s Era II). - Faleeha Zehra Kazmi H.O.D, Persian Department, LCWU, Lahore, Punjab, Pakistan. Assistant Professor, Department of Urdu, GCU, Lahore, Punjab, Farzana Riaz Pakistan. Email: [email protected] Syeda Hira Gilani PhD. Scholar, Persian Department, LCWU, Lahore, Punjab, Pakistan. Mysticism is defined as a search of God, Spiritual truth and ultimate reality. It is a practice of Abstract religious ideologies, myths, ethics and ecstasies. The Christian mysticism is the practise or theory which is within Christianity. The Jewish mysticism is theosophical, meditative and practical. A school of practice that emphasizes the search for Allah is defined as Islamic mysticism. It is believed that the earliest figure of Sufism is Prophet Muhammad (PBUH). Different Sufis and their writings have http://dx.doi.org/10.31703/gssr.2019(IV played an important role in guidance and counselling of people and Key Words: peaceful co-existence in the society. Mughal era was an important period Sufism, Mystic poetry, regarding Sufism in the subcontinent. The Mughal kings were devotees of URL: Mughal dynasty, different Sufi orders and promoted Sufism and Sufi literature. It is said that | Aurangzeb Alamgir was against Sufism, but a lot of Mystic prose and Aurangzeb Alamgir, poetic work can be seen during Aurangzeb Alamgir’s era. In this article, 49 Habib Ullah Hashmi. ). we will discuss Mystic Poetry and Prose of Aurangzeb’s period. I I - Introduction Mysticism or Sufism can be defined as search of God, spiritual truth and ultimate reality.