Coke Studio Pakistan: an Ode to Eastern Music with a Western Touch

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GOVT-PUNJAB Waitinglist Nphs.Pdf

WAITING LIST SUMMARY DATE & TIME 20-04-2021 02:21:11 PM BALLOT CATEGORY GOVT-PUNJAB TOTAL WAITING APPLICANTS 8711 WAITING LIST OF APPLICANTS S No. Receipt ID Applicant Name Father Name CNIC 1 27649520 SHABAN ALI MUHAMMAD ABBAS ADIL 3520106922295 2 27649658 Waseem Abbas Qalab Abbas 3520113383737 3 27650644 Usman Hiader Sajid Abbasi 3650156358657 4 27651140 Adil Baig Ghulam Sarwar 3520240247205 5 27652673 Nadeem Akhtar Muhammad Mumtaz 4220101849351 6 27653461 Imtiaz Hussain Zaidi Shasmshad Hussain Zaidi 3110116479593 7 27654564 Bilal Hussain Malik tasadduq Hussain 3640261377911 8 27658485 Zahid Nazir Nazir Ahmed 3540173750321 9 27659188 Muhammad Bashir Hussain Muhammad Siddique 3520219305241 10 27659190 IFTIKHAR KHAN SHER KHAN 3520226475101 ------------------- ------------------- ------------------- ------------------- Director Housing-XII (LDAC NPA) Director Finance Director IT (I&O) Chief Town Planner Note: This Ballot is conducted by PITB on request of DG LDA. PITB is not responsible for any data Anomalies. Ballot Type: GOVT-PUNJAB Date&time : Tuesday, Apr 20, 2021 02:21 PM Page 1 of 545 WAITING LIST OF APPLICANTS S No. Receipt ID Applicant Name Father Name CNIC 11 27659898 Maqbool Ahmad Muhammad Anar Khan 3440105267405 12 27660478 Imran Yasin Muhammad Yasin 3540219620181 13 27661528 MIAN AZIZ UR REHMAN MUHAMMAD ANWAR 3520225181377 14 27664375 HINA SHAHZAD MUHAMMAD SHAHZAD ARIF 3520240001944 15 27664446 SAIRA JABEEN RAZA ALI 3110205697908 16 27664597 Maded Ali Muhammad Boota 3530223352053 17 27664664 Muhammad Imran MUHAMMAD ANWAR 3520223937489 -

The World Makes Music Credits

THE WORLD MAKES MUSIC CREDITS Director Margriet Jansen With Bert Boogaard Lucien Brazil Miriam Brenner Arne Broekhoven Karin Elich Sander Friedeman Bilal Gebara Els van der Linden Raj Mohan Achmed Sadat Merel Simons Lars de Wilde Director of Photography Marcel Prins Sound Jan Wouter Stam en Jillis Schriel Editor Diego Gutiérrez Supervising editor Danniel Danniel Fundraising Ineke Smits Music rights clearance Ruby van der Linden – Yourownrights Music & Publishing Agency RTV Utrecht Machteld Smits en Neske Kraai Post production Sound Sander Friedeman Metropolisfilm Titles Guido van Eekelen Metropolisfilm Colour grading Jef Grosfeld alias KID JEF Translation and subtitles Helene Reid Subtext Translations Producer Jean Hellwig Music works in order of appearances THE CLICK SONG (Qongqothwane) Miriam Makeba (1932 – 2008) composers and authors: Ronnie Modise Majola Sehume, Rufus Khoza, Dambuza Mdledle Nathan and Joseph Mogotsi publisher: Gallo Music Publishers administrated by Warner/Chappell Music Holland B.V. recordings: Oudejaarscompilatie 1979 (BNN/VARA) NIRAN Bixiga70 composer: Bixiga70 publisher: La Chunga Music Publishing / Edition Beatglitter recordings: RASA Utrecht, 2016 (Vista Far Reaching Visuals) OCUPAI Bixiga70 composer: Romulo Nardes, Cuca Ferreira and Bixiga 70 publisher: La Chunga Music Publishing / Edition Beatglitter recordings: RASA Utrecht, 2016 (Vista Far Reaching Visuals) FURAHI Zap Mama composer: Marie Daulne album: SABSYLMA, 1994 recordings: North Sea Jazz Festival 1997 (NPS) TANGO AL MAR Faiz ali Faiz, Duquende, Miguel -

Qawwali – Lobgesänge Aus Dem Punjab Faiz Ali Faiz & Party

WELTMUSIK IM MOZART SAAL 27 APR 2018 MOZART SAAL QAWWALI – LOBGESÄNGE AUS DEM PUNJAB FAIZ ALI FAIZ & PARTY 229154_WiMSaal_Punjab_27_4_18.indd9154_WiMSaal_Punjab_27_4_18.indd a 110.04.180.04.18 110:130:13 MIT FREUNDLICHER UNTERSTÜTZUNG HAUPTFÖRDERER Ermöglicht durch den Kulturfonds Frankfurt RheinMain im Rahmen des Schwerpunktthemas „Transit“ Das Konzert fi ndet ohne Pause statt IMPRESSUM Herausgeber: Alte Oper Frankfurt Konzert- und Kongresszentrum GmbH Opernplatz, 60313 Frankfurt am Main, www.alteoper.de Intendant und Geschäftsführer: Dr. Stephan Pauly Mitarbeit bei Programmentwicklung, Konzeption und Planung: Gundula Tzschoppe (Programm und Produktion Alte Oper), Birgit Ellinghaus Programmheftredaktion: Anne-Kathrin Peitz Konzept: hauser lacour kommunikationsgestaltung gmbh Satz und Herstellung: Druckerei Imbescheidt Bildnachweis: S. 5: Wikipedia, Ramkishan950; S. 8: Habib Hmima; S. 11: Lucien Lung 229154_WiMSaal_Punjab_27_4_18.indd9154_WiMSaal_Punjab_27_4_18.indd b 110.04.180.04.18 110:130:13 GRUSSWORT Nach dem erfolgreichen Projektstart in der Spielzeit 2016/17 bietet die Alte Oper bereits zum zweiten Mal der Vielfalt der Musikkulturen der Welt ein Forum im Mozart Saal. Ziel der Reihe ist es, das Ver- ständnis anderer Lebenswelten über ihre Musik zu fördern. Das diesjährige Musikfest-Motto „Fremd bin ich...“, an Schuberts epochalem Liederzyklus exemplifi ziert, schlägt gleichzeitig den Bogen zu den vier Konzerten mit Weltmusik im Mozart Saal. Beide Projekte, das Musikfest und die Weltmusik-Reihe, werden vom Kulturfonds Frankfurt RheinMain gefördert. Der Themenschwerpunkt „Transit“ des Kulturfonds geht damit in sein letztes Jahr. Seit dem Start des Themas 2015 haben sich Antrag- steller/innen in rund 70 Projekten aller Sparten mit dem Schwer- punktthema auseinandergesetzt. Die Alte Oper Frankfurt hat in mehreren größeren Konzertveranstaltungen die musikalischen Dimen- sionen des Themas „Transit“ ausgelotet und sich dabei auch über den angestammten europäischen Raum hinausbewegt. -

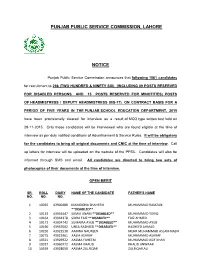

Alphabetical List of Successful Candidates for Recruitment to the Posts of Building Inspector (Bs-14) on Contract Basis For

PUNJAB PUBLIC SERVICE COMMISSION, LAHORE NOTICE Punjab Public Service Commission announces that following 1561 candidates for recruitment to 296 (TWO HUNDRED & NINETY SIX) (INCLUDING 09 POSTS RESERVED FOR DISABLED PERSONS AND 15 POSTS RESERVED FOR MINOTITIES) POSTS OF HEADMISTRESS / DEPUTY HEADMISTRESS (BS-17) ON CONTRACT BASIS FOR A PERIOD OF FIVE YEARS IN THE PUNJAB SCHOOL EDUCATION DEPARTMENT, 2015 have been provisionally cleared for interview as a result of MCQ type written test held on 29-11-2015. Only those candidates will be interviewed who are found eligible at the time of interview as per duly notified conditions of Advertisement & Service Rules. It will be obligatory for the candidates to bring all original documents and CNIC at the time of interview. Call up letters for interview will be uploaded on the website of the PPSC. Candidates will also be informed through SMS and email. All candidates are directed to bring two sets of photocopies of their documents at the time of interview. OPEN MERIT SR. ROLL DIARY NAME OF THE CANDIDATE FATHER'S NAME NO. NO. NO. 1 10065 43900486 MAMOONA SHAHEEN MUHAMMAD RAMZAN **DISABLED** 2 10133 43934447 SAMIA ANAM **DISABLED** MUHAMMAD TARIQ 3 10164 43944378 SIDRA FAIZ **DISABLED** FAIZ AHMED 4 10172 43904742 SUMAIRA AYUB **DISABLED** MUHAMMAD AYUB 5 10190 43937002 UNSA RASHEED **DISABLED** RASHEED AHMAD 6 10250 43923510 AAMNA NAUREEN MEHR MUHAMMAD ASLAM NASIR 7 10275 43922961 AASIA ASHRAF MUHAMMAD ASHRAF 8 10321 43926922 AASMA FAHEEM MUHAMMAD ASIF KHAN 9 10327 43960772 AASMA KHALID KHALID ANWAAR -

Indian Council for Cultural Relations

INDIAN COUNCIL FOR CULTURAL RELATIONS INCOMING CULTURAL DELEGATIONS April 2010–March 2011 S No. Name of the Country Period Performances artistes/Delegations held in 1. 54-Member Blind Girls Egypt 4-9 April, Delhi Chamber Orchestra 2010 2. 9-Member Amjad Sabri Pakistan 7-10 April, Delhi Group 2010 3. 5-Member Iftakhar Ahmed Pakistan 10-14 April, Delhi Group 2010 4. South Asian Students & Pakistan, 10-23 April, Visit to Delhi, Teachers (10 students & Nepal, 2010 Agra & Jaipur 3 Teachers) Sri Lanka, Bhutan, Afghanistan, Myanmar, Bangladesh and Maldives 5. 180-Member Chinese China 18-21 April, Delhi Music group (Festival of 2010 China) 6. 4-Member Ziauddin Pakistan 1-6 May, Delhi Muhhamad Group 2010 7. 3-Member Farida Khanum Pakistan 1-5 May, Delhi Group 2010 8. 2-day “Africa Festival” 1) 10-member cultural South Africa 18-22 May, Delhi, Jaipur group “UBUHLE 2010 BESINTU” 2) 11-member National Rwanda 17-22 May, Delhi, Lucknow Ballet’Urukereza’ 2010 Delhi, 3) 11-member cultural Tunisia 16-22 May, Chandigarh Group”IFRIGA” 2010 Delhi, Haridwar 4) 12-member National Malawi 17-23 May, Dance troupe “AKA Delhi & Agra KWACHA” 5) 17-member cultural Nigeria 17-22 May, Troupe 2010 9. 14-member Salsa Music Sri Lanka 29 July – Delhi Band La 33 1st August, 2010 10. 3 Day International Dance Festival by Foreign Nationals: 1) Odissi Dance by Malaysia 2nd August Delhi Ramli Ibrahim’s 2010 Group Kathak Dance by Ms. Indonesia 5th August Delhi & Aila El-Edross Mansoorie 2) Bharatanatyam by South Africa 3rd August Mr. Nhlanhla 2010 Vincent Zwane Russia Kuchipudi Dance by Ms. -

Tajdar E Haram Atif Aslam Dailymotion Mp3 Free Download

Tajdar e haram atif aslam dailymotion mp3 free download LINK TO DOWNLOAD · Coke Studio - Atif Aslam, Tajdar-e-Haram, Coke Studio Season 8, Coke Studio - Atif Aslam, Tajdar-e-Haram, Coke Studio Season 8, By Mera Pakistan. Mera Pakistan. Tajdar-e-Haram - Making Of Tajdar-e-Haram - Atif Aslam New Hamad. DailyHubs. Atif Aslam Tajdar e Haram Coke Studio Season 8 / aao madine chale by atif aslam. Just 4 Entertainment. Atif Aslam Tajdar-e. New Tajdar e Haram Download Mp3 Coke Studio Season 8 Atif Aslam Online With Full Lyrics Online Full Free Templates by BIGtheme NET renuzap.podarokideal.ru Download Mp3 Songs Free Like Hindi Mp3 Songs, Punjabi Mp3 Songs, English Mp3 Songs, Pakistani Ost Mp3 Songs, Tamil Mp3 Songs, Telugu Mp3 Songs, 8D Mp3 Songs, 3D Mp3 Songs & Many More. Tajdar-e-Haram Naat With Lyrics By Atif Aslam - MP3 Download - Tajdar-e-haram ho nigahen karam, Ham ghareebon ke din bhi sanwar jayenge, Haamie-e-bekasan kya . Download New Mp3 Songs Mp3 Audio file type: MP3 kbps. Search. Tajdar E Haram Mp3 Download Songs Pk. Coke Studio Season 8 - Tajdar-e-Haram - Atif Aslam. PopBox. Play - Download. Tajdar E Haram Full Video | Satyameva Jayate | John Abraham | Manoj Bajpayee | Sajid Wajid. T-Series. Play - Download. Tajdar E Haram Lyrical Video | Satyameva Jayate | John Abraham | Manoj . Tajdar E Haram Ho Nigah Karam Mp3 Free. Here you'll download all the songs of Tajdar E Haram Ho Nigah Karam Mp3 Free for listen and reviews. Tajdar E Haram By Atif Aslam, Tajdar E Haram is an Islamic app designed for easy access for all users and sufiyanna kalaam Lovers to get this kalaam easily and also get all Islamic Naats and more. -

Smiles, Sweets and Flags Pakistanis Celebrate Country's 71St Birthday

Volume VIII, Issue-8,August 2018 August in History Smiles, sweets and flags Pakistanis celebrate country's 71st birthday August 14, 1947: Pakistan came ment functionaries and armed into existence. forces' officials took part. August 21, 1952: Pakistan and Schools and colleges also organised India agree on the boundary pact functions for students, and a rally between East Bengal & West Bengal. was held in the capital to mark August 22, 1952: A 24 hour Independence Day. telegraph telephone service is established between East Pakistan Border security forces both on the and West Pakistan. Indian side at Wagah, and the August 16, 1952: Kashmir Afghan side at Torkham exchanged Martyrs' Day observed throughout sweets and greetings with each Pakistan. other as a gesture of goodwill. August 7, 1954: Government of Pakistan approves the National President Mamnoon Hussain and Smiles are everywhere and the official functions and ceremonies a Anthem, written by Abul Asar caretaker PM Nasirul Mulk issued atmosphere crackles with 31-gun salute in the capital and Hafeez Jullundhri and composed by separate messages addressing the excitement as Pakistanis across the 21-gun salutes in the provincial Ahmed G. Chagla. nation on August 14. country celebrate their nation's 71st capitals, as well as a major event in August 17, 1954: Pakistan defeats Courtesy: Dawn anniversary of independence. Islamabad in which top govern - England by 24 runs at Oval during its maiden tour of England. Major cities have been decked out August 1, 1960: Islamabad is in bright, colourful lights, creating declared the principal seat of the a cheery and festive atmosphere. -

Pakistan's Institutions

Pakistan’s Institutions: Pakistan’s Pakistan’s Institutions: We Know They Matter, But How Can They We Know They Matter, But How Can They Work Better? Work They But How Can Matter, They Know We Work Better? Edited by Michael Kugelman and Ishrat Husain Pakistan’s Institutions: We Know They Matter, But How Can They Work Better? Edited by Michael Kugelman Ishrat Husain Pakistan’s Institutions: We Know They Matter, But How Can They Work Better? Essays by Madiha Afzal Ishrat Husain Waris Husain Adnan Q. Khan, Asim I. Khwaja, and Tiffany M. Simon Michael Kugelman Mehmood Mandviwalla Ahmed Bilal Mehboob Umar Saif Edited by Michael Kugelman Ishrat Husain ©2018 The Wilson Center www.wilsoncenter.org This publication marks a collaborative effort between the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars’ Asia Program and the Fellowship Fund for Pakistan. www.wilsoncenter.org/program/asia-program fffp.org.pk Asia Program Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars One Woodrow Wilson Plaza 1300 Pennsylvania Avenue NW Washington, DC 20004-3027 Cover: Parliament House Islamic Republic of Pakistan, © danishkhan, iStock THE WILSON CENTER, chartered by Congress as the official memorial to President Woodrow Wilson, is the nation’s key nonpartisan policy forum for tackling global issues through independent research and open dialogue to inform actionable ideas for Congress, the Administration, and the broader policy community. Conclusions or opinions expressed in Center publications and programs are those of the authors and speakers and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Center staff, fellows, trustees, advisory groups, or any individuals or organizations that provide financial support to the Center. -

University Law College University of the Punjab, Lahore

1 University Law College University of the Punjab, Lahore. Result of Entry Test of LL.B 03 Years Morning/Afternoon Program Session (2018-2019) (Annual System) held on 12-08-2018* Total Marks: 80 Roll No. Name of Candidate Father's Name Marks 1 Nusrat Mushtaq Mushtaq Ahmed 16 2 Usman Waqas Mohammad Raouf 44 3 Ali Hassan Fayyaz Akhtar 25 4 Muneeb Ahmad Saeed Ahmad 44 5 Sajid Ali Muhammad Aslam 30 6 Muhammad Iqbal Irshad Hussain 23 7 Ameen Babar Abid Hussain Babar Absent 8 Mohsin Jamil Muhammad Jamil 24 9 Syeda Dur e Najaf Bukhari Muhammad Noor ul Ain Bukhari Absent 10 Ihtisham Haider Haji Muhammad Afzal 20 11 Muhammad Nazim Saeed Ahmad 30 12 Muhammad Wajid Abdul Waheed 22 13 Ashiq Hussain Ghulam Hussain 14 14 Abdullah Muzafar Ali 35 15 Naoman Khan Muhammad Ramzan 33 16 Abdullah Masaud Masaud Ahmad Yazdani 30 17 Muhammad Hashim Nadeem Mirza Nadeem Akhtar 39 18 Muhammad Afzaal Muhammad Arshad 13 19 Muhammad Hamza Tahir Nazeer Absent 20 Abdul Ghaffar Muhammad Majeed 19 21 Adeel Jan Ashfaq Muhammad Ashfaq 24 22 Rashid Bashir Bashir Ahmad 35 23 Touseef Akhtar Khursheed Muhammad Akhtar 42 24 Usama Nisar Nisar Ahmad 17 25 Haider Ali Zulfiqar Ali 26 26 Zeeshan Ahmed Sultan Ahmed 28 27 Hafiz Muhammad Asim Muhammad Hanif 32 28 Fatima Maqsood Maqsood Ahmad 12 29 Abdul Waheed Haji Musa Khan 16 30 Simran Shakeel Ahmad 28 31 Muhammad Sami Ullah Muhammad Shoaib 35 32 Muhammad Sajjad Shoukat Ali 27 33 Muhammad Usman Iqbal Allah Ditta Urf M. Iqbal 27 34 Noreen Shahzadi Muhammad Ramzan 19 35 Salman Younas Muhammad Younas Malik 25 36 Zain Ul Abidin Muhammad Aslam 21 37 Muhammad Zaigham Faheem Muhammad Arif 32 38 Shahid Ali Asghar Ali 37 39 Abu Bakar Jameel M. -

Finding the Way (WILL)

A handbook for Pakistan's Women Parliamentarians and Political Leaders LEADING THE WAY By Syed Shamoon Hashmi Women's Initiative for Learning & Wi Leadership She has and shel willl ©Search For Common Ground 2014 DEDICATED TO Women parliamentarians of Pakistan — past, present and aspiring - who remain committed in their political struggle and are an inspiration for the whole nation. And to those who support their cause and wish to see Pakistan stand strong as a This guidebook has been produced by Search For Common Ground Pakistan (www.sfcg.org/pakistan), an democratic and prosperous nation. international non-profit organization working to transform the way the world deals with conflict away from adversarial approaches and towards collaborative problem solving. The publication has been made possible through generous support provided by the U.S. Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights and Labor (DRL), under the project titled “Strengthening Women’s Political Participation and Leadership for Effective Democratic Governance in Pakistan.” The content of this publication is sole responsibility of SFCG Pakistan. All content, including text, illustrations and designs are the copyrighted property of SFCG Pakistan, and may not be copied, transmitted or reproduced, in part or whole, without the prior consent of Search For Common Ground Pakistan. Women's Initiative for Learning & Wi Leadership She has and shel willl ©Search For Common Ground 2014 DEDICATED TO Women parliamentarians of Pakistan — past, present and aspiring - who remain committed in their political struggle and are an inspiration for the whole nation. And to those who support their cause and wish to see Pakistan stand strong as a This guidebook has been produced by Search For Common Ground Pakistan (www.sfcg.org/pakistan), an democratic and prosperous nation. -

Book Review Essay Siren Song

Journal of International Women's Studies Volume 21 Issue 6 Article 41 August 2020 Book Review Essay Siren Song Taimur Rahman Follow this and additional works at: https://vc.bridgew.edu/jiws Part of the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Rahman, Taimur (2020). Book Review Essay Siren Song. Journal of International Women's Studies, 21(6), 516-519. Available at: https://vc.bridgew.edu/jiws/vol21/iss6/41 This item is available as part of Virtual Commons, the open-access institutional repository of Bridgewater State University, Bridgewater, Massachusetts. This journal and its contents may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. ©2020 Journal of International Women’s Studies. Siren Song1 Reviewed by Taimur Rahman2 The title of this book is extremely misleading. This is not a book about siren songs. Or perhaps it is, but not in the way you think. The book draws you in, dressed as a biography of prominent Pakistani female singers. And then, you find yourself trapped into a complex discussion of post-colonial philosophy stretching across time (in terms of philosophy) and space (in terms of continents). Hence, any review of this book cannot be a simple retelling of its contents but begs the reader to engage in some seriously strenuous thinking. I begin my review, therefore, not with what is in, but with what is not in the book - the debate that shapes the book, and to which this book is a stimulating response. -

Heer Ranjha Qissa Qawali by Zahoor Ahmad Mp3 Download

Heer ranjha qissa qawali by zahoor ahmad mp3 download LINK TO DOWNLOAD Look at most relevant Qawali heer ranjha zahoor renuzap.podarokideal.ru websites out of 15 at renuzap.podarokideal.ru Qawali heer ranjha zahoor renuzap.podarokideal.ru found at renuzap.podarokideal.ru, renuzap.podarokideal.ru, renuzap.podarokideal.ru and etc. Check th. Look at most relevant Heer ranjha mp3 qawali zahoor ahmad websites out of Million at renuzap.podarokideal.ru Heer ranjha mp3 qawali zahoor ahmad found at renuzap.podarokideal.ru, renuzap.podarokideal.ru, renuzap.podarokideal.ru and etc. Download Kawali Heer Ranjha Zahoor Ahmad Video Video Music Download Music Kawali Heer Ranjha Zahoor Ahmad Video, filetype:mp3 listen Kawali Heer Ranjha Zahoor Ahmad. Download Heer Ranjha Part 1 Zahoor Ahmed Mp3, heer ranjha part 1 zahoor ahmed, malik shani, , PT30M6S, MB, ,, 2,, , , , download-heer- ranjha-partzahoor-ahmed-mp3, WOMUSIC, renuzap.podarokideal.ru Download Planet Music Heer Ranjha Full Qawwali By Zahoor Ahmad Mp3, Metrolagu Heer Ranjha. Home» Download zahoor ahmed maqbool ahmed qawwal heer ranjha part 1 play in 3GP MP4 FLV MP3 available in p, p, p, p video formats.. Heer ni ranjha jogi ho gaya - . · Qawali pharr wanjhli badal taqdeer ranjhna teri wanjhli ty lgi hoi heer ranjhna.. (punjabi spirtual ghazal by arif feroz khan) Qawali pharr wanjhli badal taqdeer ranjhna teri wanjhli ty lgi hoi heer ranjhna.. (punjabi spirtual ghazal by arif feroz khan) Heer Ranjha Full Qawwali By Zahoor Ahmad - Duration: Khurram Rasheed , views. Heer is an extremely beautiful woman, born into a wealthy family of the Sial tribe in Jhang which is now Punjab, renuzap.podarokideal.ru (whose first name is Dheedo; Ranjha is the surname, his caste is Ranjha), a Jat of the Ranjha tribe, is the youngest of four brothers and lives in the village of Takht Hazara by the river renuzap.podarokideal.ru his father's favorite son, unlike his brothers who had to toil in.