Khawaja and the 'Amazing Bros'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

M.A Urdu and Iqbaliat (Final)

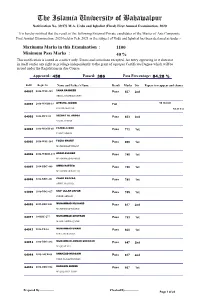

The Islamia University of Bahawalpur Notification No. 39/CS M.A. Urdu and Iqbaliat (Final) First Annual Examination, 2020 It is hereby notified that the result of the following External/Private candidates of the Master of Arts Composite First Annual Examination, 2020 held in Feb, 2021 in the subject of Urdu and Iqbaliat has been declared as under:- Maximum Marks in this Examination : 1100 Minimum Pass Marks : 40 % This notification is issued as a notice only. Errors and omissions excepted. An entry appearing in it does not in itself confer any right or privilege independently to the grant of a proper Certificate/Degree which will be issued under the Regulations in due Course. -5E -4E Appeared: 458 Passed: 386 Pass Percentage: 84.28 % Roll# Regd. No Name and Father's Name Result Marks Div Papers to reappear and chance 64001 2016-WST-348 SANA RASHEED Pass 637 2nd ABDUL RASHEED KHAN VII IX X XI 64002 2016-WNDR-19 AYESHA JAVAID Fail JAVAID AKHTAR R/A till S-22 64003 2014-IWY-88 SEERAT UL AROOJ Pass 653 2nd NASIR AHMAD 64004 2016-MOCB-05 FAZEELA BIBI Pass 712 1st JAM GAMMON 64005 2016-WST-164 FOZIA SHARIF Pass 690 1st MUHAMMAD SHARIF 64006 2016-WBDR-173 ANAM ASGHAR Pass 740 1st MUHAMMAD ASGHAR 64007 2018-BDC-440 AMNA RAFEEQ Pass 730 1st MUHAMMAD RAFEEQ 64008 2016-BDC-481 ZAHID RAZZAQ Pass 741 1st ABDUL RAZZAQ 64009 2016-BDC-427 SAIF ULLAH ZAFAR Pass 745 1st ZAFAR AHMAD 64010 2015-BDC-623 MUHAMMAD MUJAHID Pass 617 2nd MUHAMMAD AKRAM 64011 10-BDC-277 MUHAMMAD GHUFRAN Pass 753 1st MALIK ABDUL QADIR 64012 2016-US-16 MUHAMMAD UMAIR Pass 660 1st GHULAM RASOOL 64013 2016-BDC-434 MUHAMMAD AHMAD SHEHZAD Pass 647 2nd LIAQUAT ALI 64014 2015-AICB-08 SHAHZAD HUSSAIN Pass 617 2nd SYED SAJJAD HUSSAIN 64015 2016-BDC-542 HASNAIN AHMED Pass 667 1st MULAZIM HUSSAIN Prepared By--------------- Checked By-------------- Page 1 of 24 Roll# Regd. -

Appellant Mohammad-Momin-Khawaja.Pdf

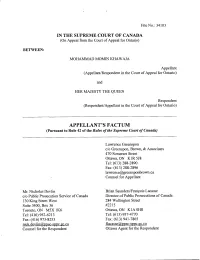

File No.: 34103 IN THE SUPREME COURT OF CANADA (On Appeal from the Court of Appeal for Ontario) BETWEEN: MOHAMMAD MOMIN KHA W AJA Appellant (Appellant/Respondent in the Court of Appeal for Ontario) and HER MAJESTY THE QUEEN Respondent (Respondent/Appellant in the Court of Appeal for Ontario) APPELLANT'S FACTUM (Pursuant to Rule 42 of the Rules of the Supreme Court of Canada) Lawrence Greenspon c/o Greenspon, Brown, & Associates 4 70 Somerset Street Ottawa, ON KlR 5J8 Tel: (613) 288-2890 Fax: (613) 288-2896 [email protected] Counsel for Appellant Mr. Nicholas Devlin Brian Saunders/Fran((ois Lacasse c/o Public Prosecution Service of Canada Director of Public Prosecutions of Canada 130 King Street West 284 Wellington Street Suite 3400, Box 36 #2215 Toronto, ON M5X 1K6 Ottawa, ON KIA OH8 Tel: (416) 952-6213 Tel: (613) 957-4770 Fax: (416) 973-8253 Fax: (613) 941-7865 nick.devlin@ppsc-sppc. gc.ca [email protected] Counsel for the Respondent Ottawa Agent for the Respondent Attorney General of Ontario Robert Houston Crown Law Office Burke Robertson 720 Bay Street 70 Gloucester Street 10'h Floor Ottawa, ON K2P OA2 Toronto, ON M5G 2Kl Tel: (416) 326-4636 Tel: (613) 236-9665 Fax: (416) 326-4656 Fax: (613) 236-4430 Counsel for Intervener Ottawa Agent for Intervener File No.: 34103 IN THE SUPREME COURT OF CANADA (On Appeal from the Court of Appeal for Ontario) BETWEEN: MOHAMMAD MOMIN KHAW AJA Appellant (Appellant/Respondent in the Court of Appeal for Ontario) and HER MAJESTY THE QUEEN Respondent (Respondent/Appellant in the Court of Appeal for Ontario) APPELLANT'S FACTUM (Pursuant to Rule 42 of the Rules of the Supreme Court of Canada) INDEX Tab Page 1. -

595 an Empirical Study of Terrorism Prosecutions in Canada

EMPIRICAL STUDY OF TERRORISM PROSECUTIONS IN CANADA 595 AN EMPIRICAL STUDY OF TERRORISM PROSECUTIONS IN CANADA: ELUCIDATING THE ELEMENTS OF THE OFFENCES MICHAEL NESBITT* AND DANA HAGG** It has now been over 15 years since Canada enacted the Anti-Terrorism Act, codifying what we think of today as Canada’s anti-terrorism criminal laws. The authors set out to canvass how these provisions have been judicially interpreted since their inception through an empirical analysis of court decisions. After exploring how courts have settled initial concerns about these provisions with respect to religious and expressive freedoms, the authors suggest that courts’ interpretations of Canada’s terrorism offences still leave us with many questions, particularly with respect to the facilitation and financing offences. The authors explore these questions and speculate about future challenges that may or may not be successful with the hopes of providing guidance to prosecutors and defence lawyers working in this area. TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION ............................................. 595 II. TERRORISM PROSECUTIONS TO DATE ............................ 599 III. JUDICIAL INTERPRETATIONS OF THE ELEMENTS OF TERRORISM OFFENCES .................................... 608 A. DEFINITIONS (SECTION 83.01)............................. 608 B. OFFENCES ............................................ 620 IV. CONCLUSIONS AND FUTURE CONSIDERATIONS ....................... 647 I. INTRODUCTION It has now been over 15 years since Canada expeditiously enacted the Anti-Terrorism -

Terrorism in Canada

Journal of Military and Strategic VOLUME 13, ISSUE 3, Spring 2011 Studies Terrorism in Canada Michael Zekulin September 11th 2011 will mark the tenth anniversary of the terrorist attacks which toppled the World Trade Center buildings in New York City and killed approximately three thousand people. These attacks marked the beginning of an escalation of global Islamic terrorism which shows no signs of fading in the near future. The purpose of this paper is to examine whether Islamic terrorism has seen a marked increase in Canada since 9/11 and further identify what this might mean for Canadians and policymakers moving forward. Investigating the terrorist incidents which have unfolded in Canada over the past ten years not only provides valuable information about the threats and challenges Canada has experienced since 9/11, it also provides clues about what we might expect moving forward. This paper argues that an analysis of terrorist incidents in Canada from 9/11 until today reveals a disturbing trend. However, it also provides a clear indication of several areas which need to be investigated and addressed in order to mitigate this threat moving forward. This paper begins by summarizing six high profile terrorist incidents which have unfolded in Canada over the past ten years. These include plots linked to the “Toronto 18,” as well as Misbahuddin Ahmed, Khurram Sher and Hiva Alizadeh, collectively referred to as the “Ottawa 3.” It also examines individuals accused of planning or supporting terrorist activities such as Said Namouh, Mohammad Khawaja, Mohamed Harkat and Sayfildin Tahir-Sharif. These case studies are presented to show the reader that Canada has faced significant threats in the ten years since 9/11, and further, that these incidents appear to be increasing. -

Reforming Madrasa Education in Pakistan; Post 9/11 Perspectives Ms Fatima Sajjad

Volume 3, Issue 1 Journal of Islamic Thought and Civilization Spring 2013 Reforming Madrasa Education in Pakistan; Post 9/11 Perspectives Ms Fatima Sajjad Abstract Pakistani madrasa has remained a subject of intense academic debate since the tragic events of 9/11 as they were immediately identified as one of the prime suspects. The aim of this paper is to examine the post 9/11 academic discourse on the subject of madrasa reform in Pakistan and identify the various themes presented in them. This paper also seeks to explore the missing perspective in this discourse; the perspective of ulama; the madrasa managers, about the Western demand to reform madrasa. This study is based on qualitative research methods. To evaluate the views of academia, this study relies on a systematic analysis of the post 9/11 discourse on this subject. To find out the views of ulama, in-depth interviews of leading Pakistani ulama belonging to all major schools of thought have been conducted. The study finds that many fears generated by early post 9/11 studies were rejected by the later ones. This study also finds that contrary to the common perception the leading ulama in Pakistan are open to the idea of madrasa reform but they prefer to do it internally as an ongoing process and not due to outside pressure. This study recommends that in order to resolve the madrasa problem in Pakistan, it is imperative to take into account the ideas and concerns of ulama running them. It is also important to take them on board in the fight against the religious militancy and terrorism in Pakistan. -

1St CABINET UNDER the PREMIERSHIP of SYED YOUSAF RAZA GILLANI, the PRIME MINISTER from 25.03.2008 to 11.02.2011

1st CABINET UNDER THE PREMIERSHIP OF SYED YOUSAF RAZA GILLANI, THE PRIME MINISTER FROM 25.03.2008 to 11.02.2011 S.NO. NAME WITH TENURE PORTFOLIO PERIOD OF PORTFOLIO 1 2 3 4 SYED YOUSAF RAZA GILLANI, PRIME MINSITER, 25.03.2008 to 11.02.2011 FEDERAL MINISTERS 1. Chaudhry Nisar Ali Khan i) Communication and 31.03.2008 to 13.05.2008 Senior Minister ii) Inter Provincial Coordination 08.04.2008 to 13.05.2008 31.03.2008 to 13.05.2008 iii) Food Agriculture & Livestock (Addl. Charge) 31.03.2008 to 13.05.2008 2. Makhdoom Amin Fahim Commerce 04.11.2008 to 11.02.2011 03.11.2008 to 11.02.2011 3. Mr. Shahid Khaqan Abbassi, Commerce 31.03.2008 to 12.05.2008 31.03.2008 to 12.05.2008 4. Dr. Arbab Alamgir Khan Communications 04.11.2008 to 11.02.2011 03.11.2008 to 11.02.2011 5. Khawaja Saad Rafique i) Culture 31.03.2008 to 13.05.2008 31.03.2008 to 13.05.2008 ii) Youth Affairs (Addl. Charge) 31.03.2008 to 13.05.2008 6. Chaudhry Ahmed Mukhtar i) Defence 31.03.2008 to 11.02.2011 31.03.2008 to 11.02.2011 ii) Textile Industry 15.04.2008 to 03.11.2008 iii) Commerce 15.04.2008 to 03.11.2008 7. Rana Tanveer Hussain Defence Production 31.03.2008 to 13.05.2008 31.03.2008 to 13.5.2008 8. Mr. Abdul Qayyum Khan Jatoi Defence Production 04.11.2008 to 03.10.2010 03.11.2008 to 03.10.2010 9. -

The European Angle to the U.S. Terror Threat Robin Simcox | Emily Dyer

AL-QAEDA IN THE UNITED STATES THE EUROPEAN ANGLE TO THE U.S. TERROR THREAT Robin Simcox | Emily Dyer THE EUROPEAN ANGLE TO THE U.S. TERROR THREAT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY • Nineteen individuals (11% of the overall total) who committed al-Qaeda related offenses (AQROs) in the U.S. between 1997 and 2011 were either European citizens or had previously lived in Europe. • The threat to America from those linked to Europe has remained reasonably constant – with European- linked individuals committing AQROs in ten of the fifteen years studied. • The majority (63%) of the nineteen European-linked individuals were unemployed, including all individuals who committed AQROs between 1998 and 2001, and from 2007 onwards. • 42% of individuals had some level of college education. Half of these individuals committed an AQRO between 1998 and 2001, while the remaining two individuals committed offenses in 2009. • 16% of offenders with European links were converts to Islam. Between 1998 and 2001, and between 2003 and 2009, there were no offenses committed by European-linked converts. • Over two thirds (68%) of European-linked offenders had received terrorist training, primarily in Afghanistan. However, nine of the ten individuals who had received training in Afghanistan committed their AQRO before 2002. Only one individual committed an AQRO afterwards (Oussama Kassir, whose charges were filed in 2006). • Among all trained individuals, 92% committed an AQRO between 1998 and 2006. • 16% of individuals had combat experience. However, there were no European-linked individuals with combat experience who committed an AQRO after 2005. • Active Participants – individuals who committed or were imminently about to commit acts of terrorism, or were formal members of al-Qaeda – committed thirteen AQROs (62%). -

SUFIS and THEIR CONTRIBUTION to the CULTURAL LIFF of MEDIEVAL ASSAM in 16-17"' CENTURY Fttasfter of ^Hilojiopl)?

SUFIS AND THEIR CONTRIBUTION TO THE CULTURAL LIFF OF MEDIEVAL ASSAM IN 16-17"' CENTURY '•"^•,. DISSERTATION SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF fttasfter of ^hilojiopl)? ' \ , ^ IN . ,< HISTORY V \ . I V 5: - • BY NAHIDA MUMTAZ ' Under the Supervision of DR. MOHD. PARVEZ CENTRE OF ADVANCED STUDY DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALIGARH (INDIA) 2010 DS4202 JUL 2015 22 CENTRE OF ADVANCED STUDY Department of History Aligarh Muslim University Aligarh-202 002 Dr. Mohd. Parwez Dated: June 9, 2010 Reader To Whom It May Concern This is to certify that the dissertation entitled "Sufis and their Contribution to the Cultural Life of Medieval Assam in 16-17^^ Century" is the original work of Ms. Nahida Muxntaz completed under my supervision. The dissertation is suitable for submission and award of degree of Master of Philosophy in History. (Dr. MoMy Parwez) Supervisor Telephones: (0571) 2703146; Fax No.: (0571) 2703146; Internal: 1480 and 1482 Dedicated To My Parents Acknowledgements I-11 Abbreviations iii Introduction 1-09 CHAPTER-I: Origin and Development of Sufism in India 10 - 31 CHAPTER-II: Sufism in Eastern India 32-45 CHAPTER-in: Assam: Evolution of Polity 46-70 CHAPTER-IV: Sufis in Assam 71-94 CHAPTER-V: Sufis Influence in Assam: 95 -109 Evolution of Composite Culture Conclusion 110-111 Bibliography IV - VlU ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS It is pleasant duty for me to acknowledge the kindness of my teachers and friends from whose help and advice I have benefited. It is a rare obligation to express my gratitude to my supervisor Dr. Mohd. -

Professor James Winston Morris Department of Theology Boston College E-Mail: [email protected] Office Telephone: 617-552-0571 Many of Prof

1 Professor James Winston Morris Department of Theology Boston College e-mail: [email protected] Office telephone: 617-552-0571 Many of Prof. Morris’s articles and reviews, and some older books, are now freely available in searchable and downloadable .pdf format at http://dcollections.bc.edu/james_morris PREVIOUS ACADEMIC POSITIONS: 2006-present Boston College, Professor, Department of Theology. 1999-2006 University of Exeter, Professor, Sharjah Chair of Islamic Studies and Director of Graduate Studies and Research, Institute of Arab and Islamic Studies. 1989-99: Oberlin College: Assoc. Professor, Department of Religion. 1988-89: Temple University: Asst. Professor, Department of Religion. 1987-88: Princeton University: Visiting Professor, Department of Religion and Department of Near Eastern Studies. 1981-87: Institute of Ismaili Studies, Paris/London (joint graduate program in London with McGill University, Institute of Islamic Studies): Professor, Department of Graduate Studies and Research. EDUCATION AND ACADEMIC HONORS: HARVARD UNIVERSITY PH.D, NEAR EASTERN LANGUAGES CAMBRIDGE, MASSACHUSETTS AND CIVILIZATIONS, 1980 Major field: Islamic philosophy and theology; minor fields: classical philosophy, Arabic language and literature, Persian language and literature, . Fellowships: Danforth Graduate Fellowship (1971-1978); Whiting Foundation Dissertation Fellowship (1978-1979); foreign research fellowships (details below). UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO B.A., CIVILIZATIONAL CHICAGO, ILLINOIS STUDIES, 1971 Awards and Fellowships: University Scholar; -

Mapping the Global Muslim Population

MAPPING THE GLOBAL MUSLIM POPULATION A Report on the Size and Distribution of the World’s Muslim Population October 2009 About the Pew Forum on Religion & Public Life This report was produced by the Pew Research Center’s Forum on Religion & Public Life. The Pew Forum delivers timely, impartial information on issues at the intersection of religion and public affairs. The Pew Forum is a nonpartisan, nonadvocacy organization and does not take positions on policy debates. Based in Washington, D.C., the Pew Forum is a project of the Pew Research Center, which is funded by The Pew Charitable Trusts. This report is a collaborative effort based on the input and analysis of the following individuals: Pew Forum on Religion & Public Life Communications and Web Publishing Luis Lugo, Director Erin O’Connell, Associate Director, Communications Oliver Read, Web Manager Research Loralei Coyle, Communications Manager Alan Cooperman, Associate Director, Research Robert Mills, Communications Associate Brian J. Grim, Senior Researcher Liga Plaveniece, Program Coordinator Mehtab S. Karim, Visiting Senior Research Fellow Sahar Chaudhry, Research Analyst Pew Research Center Becky Hsu, Project Consultant Andrew Kohut, President Jacqueline E. Wenger, Research Associate Paul Taylor, Executive Vice President Kimberly McKnight, Megan Pavlischek and Scott Keeter, Director of Survey Research Hilary Ramp, Research Interns Michael Piccorossi, Director of Operations Michael Keegan, Graphics Director Editorial Alicia Parlapiano, Infographics Designer Sandra Stencel, Associate Director, Editorial Russell Heimlich, Web Developer Andrea Useem, Contributing Editor Tracy Miller, Editor Sara Tisdale, Assistant Editor Visit http://pewforum.org/docs/?DocID=450 for the interactive, online presentation of Mapping the Global Muslim Population. -

Digest of Terrorist Cases

back to navigation page Vienna International Centre, PO Box 500, 1400 Vienna, Austria Tel.: (+43-1) 26060-0, Fax: (+43-1) 26060-5866, www.unodc.org Digest of Terrorist Cases United Nations publication Printed in Austria *0986635*V.09-86635—March 2010—500 UNITED NATIONS OFFICE ON DRUGS AND CRIME Vienna Digest of Terrorist Cases UNITED NATIONS New York, 2010 This publication is dedicated to victims of terrorist acts worldwide © United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, January 2010. The designations employed and the presentation of material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. This publication has not been formally edited. Publishing production: UNOV/DM/CMS/EPLS/Electronic Publishing Unit. “Terrorists may exploit vulnerabilities and grievances to breed extremism at the local level, but they can quickly connect with others at the international level. Similarly, the struggle against terrorism requires us to share experiences and best practices at the global level.” “The UN system has a vital contribution to make in all the relevant areas— from promoting the rule of law and effective criminal justice systems to ensuring countries have the means to counter the financing of terrorism; from strengthening capacity to prevent nuclear, biological, chemical, or radiological materials from falling into the -

Download Testimony (95.2

To the Esteemed Members of the United States Senate Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs In the matter related to the hearing titled, “Jihad 2.0: Social Media in the Next Evolution of Terrorist Recruitment.” Submission by Mr. Mubin Shaikh On September 11, 2001 I was driving to work when I first heard a plane had struck one of the two towers of the World Trade Center building. Immediately, I exclaimed aloud, “AllahuAkbar” (God is Great). My celebratory moment was quickly muted when I asked myself; what if the very office building I was working in, was similarly struck by a plane? I would have perished along with everyone else just as those innocent people perished on that day. For me and many others, September 11, 2001 was – for all intents and purposes – the beginning of the end of my commitment to the extremist mindset. Allow me to explain how I even got here in the first place. I was born and raised in Toronto, Canada to Indian immigrants. As a child, I grew up attending a very conservative brand of “Madressah,” which was an imported version of what you would find in India and Pakistan: rows of boys (separated from the girls) sitting at wooden benches, rocking back and forth, reciting the Quran in Arabic but not understanding a word of what was being read. Contrast that with my daily life of attending public school, which was the complete opposite of the rigid, fundamentalist manner of education of the Madressah. Here, I could actually talk to girls and have a normal, functional relationship with them without it being some grievous sin.