Religious Practices at Sufi Shrines in the Punjab

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sammamish Masjid Is Seeking a Full Time Imam

Sammamish Masjid is seeking a full time Imam Background &Summary Sammamish Masjid is located in the beautiful Pacific North West, around 15 miles east of Seattle. Sammamish is a beautiful city with more than 200 Muslim families living in and around its vicinity. The Sammamish Muslim community represents Sunni Muslims from a diverse ethnic and cultural backgrounds. This community is growing fast, and requires a dynamic leader/imam for its Masjid to fulfill the religious needs of this growing community. The Imam will liaise with Muslim worshippers at the Sammamish Masjid, will ensure that Imam Responsibilities (listed below) are performed to the highest satisfactory level of the Sammamish Muslim Community. The Imam is expected to grow and develop a strong community relationship (not limited to the Muslim community). In addition to the day to day Imam Responsibilities, the Imam will lead liaison between the Sammamish Muslim community and other Muslim communities in the Puget Sound Area. The Imam will participate in events that will promote the unification of all Muslim communities in the region as well as outreach events with non-Muslim communities. Bonding especially with the youth to educate and train them in Islamic traditions and etiquettes are some of the crucial functions the Imam is expected to lead. The individual will adhere to the Sammamish Muslim Association (SMA) by-laws, and report directly to the SMA Trustee chairman, and SMA board through its president or as delegated in special circumstances. RESPONSIBILITIES Lead the five daily prayers during what is to be agreed upon as working days. (working days will be prescribed and agreed upon by the board and the Imam to accommodate two days off per 7-day week – Friday, Saturday, and Sunday excluded) Conduct Friday Jumuah prayer sermon including a youth dedicated Jumuah Conduct Ramadan prayers, including Quiyam U’Leil, and Taraweeh Participate in the development of curriculum for after school and weekend educational programs for kids of all ages. -

Understanding the Concept of Islamic Sufism

Journal of Education & Social Policy Vol. 1 No. 1; June 2014 Understanding the Concept of Islamic Sufism Shahida Bilqies Research Scholar, Shah-i-Hamadan Institute of Islamic Studies University of Kashmir, Srinagar-190006 Jammu and Kashmir, India. Sufism, being the marrow of the bone or the inner dimension of the Islamic revelation, is the means par excellence whereby Tawhid is achieved. All Muslims believe in Unity as expressed in the most Universal sense possible by the Shahadah, la ilaha ill’Allah. The Sufi has realized the mysteries of Tawhid, who knows what this assertion means. It is only he who sees God everywhere.1 Sufism can also be explained from the perspective of the three basic religious attitudes mentioned in the Qur’an. These are the attitudes of Islam, Iman and Ihsan.There is a Hadith of the Prophet (saw) which describes the three attitudes separately as components of Din (religion), while several other traditions in the Kitab-ul-Iman of Sahih Bukhari discuss Islam and Iman as distinct attitudes varying in religious significance. These are also mentioned as having various degrees of intensity and varieties in themselves. The attitude of Islam, which has given its name to the Islamic religion, means Submission to the Will of Allah. This is the minimum qualification for being a Muslim. Technically, it implies an acceptance, even if only formal, of the teachings contained in the Qur’an and the Traditions of the Prophet (saw). Iman is a more advanced stage in the field of religion than Islam. It designates a further penetration into the heart of religion and a firm faith in its teachings. -

Intra-Faith Dialogue in Mali What Role for Religious Actors in Managing Local Conflicts?

Intra-faith dialogue in Mali What role for religious actors in managing local conflicts? The jihadist groups that overran the north and imams, ulema, qur’anic masters and leaders of parts of central Mali in 2012 introduced a ver- Islamic associations. These actors were orga- sion of Islam that advocates the comprehen- nised into six platforms of religious actors sive enforcement of Sharia law. Despite the based in Gao, Timbuktu, Mopti, Taoudeni, Mé- crimes committed by these groups, some naka and Ségou. These platforms seek to communities perceive them as providers of se- contribute to easing intra-faith tensions, as well curity and equity in the application of justice. as to prevent and manage local conflicts, These jihadist influences have polarised com- whether communal or religious in nature. The munities and resulted in tensions between the examples below illustrate their work. diverse branches of Islam. Against this background, in 2015 the Centre for Humanitarian Dialogue (HD) began facilitating intra-faith dialogue among nearly 200 local MOPTI Ending competitive recitals of the Quran For nearly 40 years, the young of religious actors in engaging gious leaders asked the talibés or religious students with the talibés. groups to suspend “Missou”, around Mopti have regularly which they agreed to do. The The platform identified around competed in duels to see who groups’ marabouts were relie- 30 recital groups, mostly in can give the most skilful reci- ved to see that other religious Socoura, Fotama, Mopti and tal of the Quran. Known as leaders shared their concerns Bandiagara, and began awar- “Missou”, these widespread about these duels and added eness-raising efforts with se- duels can gather up to 60 their support to the initiative. -

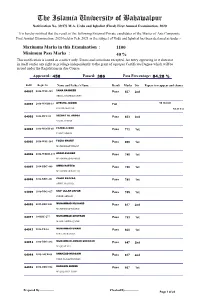

M.A Urdu and Iqbaliat (Final)

The Islamia University of Bahawalpur Notification No. 39/CS M.A. Urdu and Iqbaliat (Final) First Annual Examination, 2020 It is hereby notified that the result of the following External/Private candidates of the Master of Arts Composite First Annual Examination, 2020 held in Feb, 2021 in the subject of Urdu and Iqbaliat has been declared as under:- Maximum Marks in this Examination : 1100 Minimum Pass Marks : 40 % This notification is issued as a notice only. Errors and omissions excepted. An entry appearing in it does not in itself confer any right or privilege independently to the grant of a proper Certificate/Degree which will be issued under the Regulations in due Course. -5E -4E Appeared: 458 Passed: 386 Pass Percentage: 84.28 % Roll# Regd. No Name and Father's Name Result Marks Div Papers to reappear and chance 64001 2016-WST-348 SANA RASHEED Pass 637 2nd ABDUL RASHEED KHAN VII IX X XI 64002 2016-WNDR-19 AYESHA JAVAID Fail JAVAID AKHTAR R/A till S-22 64003 2014-IWY-88 SEERAT UL AROOJ Pass 653 2nd NASIR AHMAD 64004 2016-MOCB-05 FAZEELA BIBI Pass 712 1st JAM GAMMON 64005 2016-WST-164 FOZIA SHARIF Pass 690 1st MUHAMMAD SHARIF 64006 2016-WBDR-173 ANAM ASGHAR Pass 740 1st MUHAMMAD ASGHAR 64007 2018-BDC-440 AMNA RAFEEQ Pass 730 1st MUHAMMAD RAFEEQ 64008 2016-BDC-481 ZAHID RAZZAQ Pass 741 1st ABDUL RAZZAQ 64009 2016-BDC-427 SAIF ULLAH ZAFAR Pass 745 1st ZAFAR AHMAD 64010 2015-BDC-623 MUHAMMAD MUJAHID Pass 617 2nd MUHAMMAD AKRAM 64011 10-BDC-277 MUHAMMAD GHUFRAN Pass 753 1st MALIK ABDUL QADIR 64012 2016-US-16 MUHAMMAD UMAIR Pass 660 1st GHULAM RASOOL 64013 2016-BDC-434 MUHAMMAD AHMAD SHEHZAD Pass 647 2nd LIAQUAT ALI 64014 2015-AICB-08 SHAHZAD HUSSAIN Pass 617 2nd SYED SAJJAD HUSSAIN 64015 2016-BDC-542 HASNAIN AHMED Pass 667 1st MULAZIM HUSSAIN Prepared By--------------- Checked By-------------- Page 1 of 24 Roll# Regd. -

Al-Ghazali's Integral Epistemology: a Critical Analysis of the Jewels of the Quran

American University in Cairo AUC Knowledge Fountain Theses and Dissertations 6-1-2017 Al-Ghazali's integral epistemology: A critical analysis of the jewels of the Quran Amani Mohamed Elshimi Follow this and additional works at: https://fount.aucegypt.edu/etds Recommended Citation APA Citation Elshimi, A. (2017).Al-Ghazali's integral epistemology: A critical analysis of the jewels of the Quran [Master’s thesis, the American University in Cairo]. AUC Knowledge Fountain. https://fount.aucegypt.edu/etds/618 MLA Citation Elshimi, Amani Mohamed. Al-Ghazali's integral epistemology: A critical analysis of the jewels of the Quran. 2017. American University in Cairo, Master's thesis. AUC Knowledge Fountain. https://fount.aucegypt.edu/etds/618 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by AUC Knowledge Fountain. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of AUC Knowledge Fountain. For more information, please contact [email protected]. School of Humanities and Social Sciences Al-Ghazali’s Integral Epistemology: A Critical Analysis of The Jewels of the Quran A Thesis Submitted to The Department of Arab and Islamic Civilization in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts by Amani Elshimi 000-88-0001 under the supervision of Dr. Mohamed Serag Professor of Islamic Studies Thesis readers: Dr. Steffen Stelzer Professor of Philosophy, The American University in Cairo Dr. Aliaa Rafea Professor of Sociology, Ain Shams University; Founder of The Human Foundation NGO May 2017 Acknowledgements First and foremost, Alhamdulillah - my gratitude to God for the knowledge, love, light and faith. -

The Ultimate Dimension of Life’ During His(RA) Lifetime

ABOUT THE BOOK This book unveils the glory and marvellous reality of a spiritual and ascetic personality who followed a rare Sufi Order called ‘Malamatia’ (The Carrier of Blame). Being his(RA) chosen Waris and an ardent follower, the learned and blessed author of the book has narrated the sacred life style and concern of this exalted Sufi in such a profound style that a reader gets immersed in the mystic realities of spiritual life. This book reflects the true essence of the message of Islam and underscores the need for imbibing within us, a humane attitude of peace, amity, humility, compassion, characterized by selfless THE ULTIMATE and passionate love for the suffering humanity; disregarding all prejudices DIMENSION OF LIFE and bias relating to caste, creed, An English translation of the book ‘Qurb-e-Haq’ written on the colour, nationality or religion. Surely, ascetic life and spiritual contemplations of Hazrat Makhdoom the readers would get enlightened on Syed Safdar Ali Bukhari (RA), popularly known as Qalandar the purpose of creation of the Pak Baba Bukhari Kakian Wali Sarkar. His(RA) most devout mankind by The God Almighty, and follower Mr Syed Shakir Uzair who was fondly called by which had been the point of focus and Qalandar Pak(RA) as ‘Syed Baba’ has authored the book. He has been an all-time enthusiast and zealous adorer of Qalandar objective of the Holy Prophet Pak(RA), as well as an accomplished and acclaimed senior Muhammad PBUH. It touches the Producer & Director of PTV. In his illustrious career spanning most pertinent subject in the current over four decades, he produced and directed many famous PTV times marred by hatred, greed, lust, Plays, Drama Serials and Programs including the breathtaking despondency, affliction, destruction, and amazing program ‘Al-Rehman’ and the magnificient ‘Qaseeda Burda Sharif’. -

Albanian Contemporary Qur'anic Exegesis: Sheikh

ALBANIAN CONTEMPORARY QUR’ANIC EXEGESIS: SHEIKH HAFIZ IBRAHIM DALLIU’S COMMENTARY (Tafsir Al-Quran Kontemporari Albania: Ulasan Oleh Sheikh Hafiz Ibrahim Dalliu) Hajredin Hoxha1 ABSTRACT: The objective of this study is to explore and analyze the main intellectual and religious trends and tendencies in the writings of Albanian Ulema in their dealing with Qur’anic studies, in the modern time, in the Balkan Peninsula in Europe. In conducting this study, the researcher has utilized inductive, historical, critical and analytical methodologies. The Albanian lands in the Balkan Peninsula were governed and ruled by the Islamic Ottoman Empire for almost five centuries. Historically, to some extent and despite the conflicts and clashes, Albanians were able to show to the world a very good sample of peace, unity and harmony among themselves, as a multi religious and multi ethnic society. The attention and the engagement of the Albanian Ulema with the Qur’anic sciences have been tremendous since the spread of Islam, and have to be taken into consideration. Despite the tough and serious political, economic and religious challenges in the 19th and 20th centuries, they were not distracted from conducting their learning and teaching affaires. As a result of very close contacts and relations with different ideologies, cultures and civilizations within the Ottoman mixed ethnicity and in the middle-east, the researcher based on different sources, was able to identify and discover Sunni Maturidi dogmatic approach in dealing with Quranic Exegesis in the Commentary of Sheikh Hafiz Ibrahim Dalliu-a case study. The results and conclusions of this study are to be taken into consideration also, especially when we know that the current and modern historical sources of Albania are deviated almost completely and not to be trusted at all, because they failed to show to the Albanian people a real picture of Islam. -

Muslim Saints of South Asia

MUSLIM SAINTS OF SOUTH ASIA This book studies the veneration practices and rituals of the Muslim saints. It outlines the principle trends of the main Sufi orders in India, the profiles and teachings of the famous and less well-known saints, and the development of pilgrimage to their tombs in India, Pakistan and Bangladesh. A detailed discussion of the interaction of the Hindu mystic tradition and Sufism shows the polarity between the rigidity of the orthodox and the flexibility of the popular Islam in South Asia. Treating the cult of saints as a universal and all pervading phenomenon embracing the life of the region in all its aspects, the analysis includes politics, social and family life, interpersonal relations, gender problems and national psyche. The author uses a multidimen- sional approach to the subject: a historical, religious and literary analysis of sources is combined with an anthropological study of the rites and rituals of the veneration of the shrines and the description of the architecture of the tombs. Anna Suvorova is Head of Department of Asian Literatures at the Institute of Oriental Studies, Russian Academy of Sciences, Moscow. A recognized scholar in the field of Indo-Islamic culture and liter- ature, she frequently lectures at universities all over the world. She is the author of several books in Russian and English including The Poetics of Urdu Dastaan; The Sources of the New Indian Drama; The Quest for Theatre: the twentieth century drama in India and Pakistan; Nostalgia for Lucknow and Masnawi: a study of Urdu romance. She has also translated several books on pre-modern Urdu prose into Russian. -

Shiism and Sectarian Conflict in Pakistan Identity Politics, Iranian Influence, and Tit-For-Tat Violence

Combating Terrorism Center at West Point Occasional Paper Series Shiism and Sectarian Conflict in Pakistan Identity Politics, Iranian Influence, and Tit-for-Tat Violence Hassan Abbas September 22, 2010 1 2 Preface As the first decade of the 21st century nears its end, issues surrounding militancy among the Shi‛a community in the Shi‛a heartland and beyond continue to occupy scholars and policymakers. During the past year, Iran has continued its efforts to extend its influence abroad by strengthening strategic ties with key players in international affairs, including Brazil and Turkey. Iran also continues to defy the international community through its tenacious pursuit of a nuclear program. The Lebanese Shi‛a militant group Hizballah, meanwhile, persists in its efforts to expand its regional role while stockpiling ever more advanced weapons. Sectarian violence between Sunnis and Shi‛a has escalated in places like Saudi Arabia, Yemen, Bahrain, and not least, Pakistan. As a hotbed of violent extremism, Pakistan, along with its Afghan neighbor, has lately received unprecedented amounts of attention among academics and policymakers alike. While the vast majority of contemporary analysis on Pakistan focuses on Sunni extremist groups such as the Pakistani Taliban or the Haqqani Network—arguably the main threat to domestic and regional security emanating from within Pakistan’s border—sectarian tensions in this country have attracted relatively little scholarship to date. Mindful that activities involving Shi‛i state and non-state actors have the potential to affect U.S. national security interests, the Combating Terrorism Center is therefore proud to release this latest installment of its Occasional Paper Series, Shiism and Sectarian Conflict in Pakistan: Identity Politics, Iranian Influence, and Tit-for-Tat Violence, by Dr. -

Copyright by Mohammad Raisur Rahman 2008

Copyright by Mohammad Raisur Rahman 2008 The Dissertation Committee for Mohammad Raisur Rahman certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Islam, Modernity, and Educated Muslims: A History of Qasbahs in Colonial India Committee: _____________________________________ Gail Minault, Supervisor _____________________________________ Cynthia M. Talbot _____________________________________ Denise A. Spellberg _____________________________________ Michael H. Fisher _____________________________________ Syed Akbar Hyder Islam, Modernity, and Educated Muslims: A History of Qasbahs in Colonial India by Mohammad Raisur Rahman, B.A. Honors; M.A.; M.Phil. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin August 2008 Dedication This dissertation is dedicated to the fond memories of my parents, Najma Bano and Azizur Rahman, and to Kulsum Acknowledgements Many people have assisted me in the completion of this project. This work could not have taken its current shape in the absence of their contributions. I thank them all. First and foremost, I owe my greatest debt of gratitude to my advisor Gail Minault for her guidance and assistance. I am grateful for her useful comments, sharp criticisms, and invaluable suggestions on the earlier drafts, and for her constant encouragement, support, and generous time throughout my doctoral work. I must add that it was her path breaking scholarship in South Asian Islam that inspired me to come to Austin, Texas all the way from New Delhi, India. While it brought me an opportunity to work under her supervision, I benefited myself further at the prospect of working with some of the finest scholars and excellent human beings I have ever known. -

The Institution of the Akal Takht: the Transformation of Authority in Sikh History

religions Article The Institution of the Akal Takht: The Transformation of Authority in Sikh History Gurbeer Singh Department of Religious Studies, University of California, Riverside, CA 92521, USA; [email protected] Abstract: The Akal Takht is considered to be the central seat of authority in the Sikh tradition. This article uses theories of legitimacy and authority to explore the validity of the authority and legitimacy of the Akal Takht and its leaders throughout time. Starting from the initial institution of the Akal Takht and ending at the Akal Takht today, the article applies Weber’s three types of legitimate authority to the various leaderships and custodianships throughout Sikh history. The article also uses Berger and Luckmann’s theory of the symbolic universe to establish the constant presence of traditional authority in the leadership of the Akal Takht. Merton’s concept of group norms is used to explain the loss of legitimacy at certain points of history, even if one or more types of Weber’s legitimate authority match the situation. This article shows that the Akal Takht’s authority, as with other political religious institutions, is in the reciprocal relationship between the Sikh population and those in charge. This fluidity in authority is used to explain and offer a solution on the issue of authenticity and authority in the Sikh tradition. Keywords: Akal Takht; jathedar; Sikh institutions; Sikh Rehat Maryada; Shiromani Gurdwara Parbandhak Committee (SGPC); authority; legitimacy Citation: Singh, Gurbeer. 2021. The Institution of the Akal Takht: The 1. Introduction Transformation of Authority in Sikh History. Religions 12: 390. https:// The Akal Takht, originally known as the Akal Bunga, is the seat of temporal and doi.org/10.3390/rel12060390 spiritual authority of the Sikh tradition. -

Spiritual Rituals at Sufi Shrines in Punjab: a Study of Khawaja Shams-Ud-Din Sialvi, Sial Sharif and Meher Ali Shah of Golra Sharif Vol

Global Regional Review (GRR) URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.31703/grr.2019(IV-I).23 Spiritual Rituals at Sufi Shrines in Punjab: A Study of Khawaja Shams-Ud-Din Sialvi, Sial Sharif and Meher Ali Shah of Golra Sharif Vol. IV, No. I (Winter 2019) | Page: 209 ‒ 214 | DOI: 10.31703/grr.2019(IV-I).23 p- ISSN: 2616-955X | e-ISSN: 2663-7030 | ISSN-L: 2616-955X Abdul Qadir Mushtaq* Muhammad Shabbir† Zil-e-Huma Rafique‡ This research narrates Sufi institution’s influence on the religious, political and cultural system. The masses Abstract frequently visit Sufi shrines and perform different rituals. The shrines of Khawaja Shams-Ud-Din Sialvi of Sial Sharif and Meher Ali Shah of Golra Sharif have been taken as case study due to their religious importance. It is a common perception that people practice religion according to their cultural requirements and this paper deals rituals keeping in view cultural practices of the society. It has given new direction to the concept of “cultural dimensions of religious analysis” by Clifford Geertz who says “religion: as a cultural system” i.e. a system of symbols which synthesizes a people’s ethos and explain their words. Eaton and Gilmartin have presented same historical analysis of the shrines of Baba Farid, Taunsa Sharif and Jalalpur Sharif. This research is descriptive and analytical. Primary and secondary sources have been consulted. Key Words: Khanqah, Dargah, SajjadaNashin, Culture, Esoteric, Exoteric, Barakah, Introduction Sial Sharif is situated in Sargodha region (in the center of Sargodha- Jhang road). It is famous due to Khawaja Shams-Ud-Din Sialvi, a renowned Chishti Sufi.