Shari'ah Criminal Law in Northern Nigeria

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

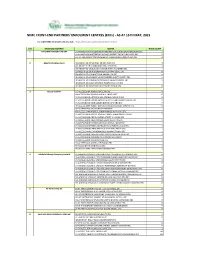

NIMC FRONT-END PARTNERS' ENROLMENT CENTRES (Ercs) - AS at 15TH MAY, 2021

NIMC FRONT-END PARTNERS' ENROLMENT CENTRES (ERCs) - AS AT 15TH MAY, 2021 For other NIMC enrolment centres, visit: https://nimc.gov.ng/nimc-enrolment-centres/ S/N FRONTEND PARTNER CENTER NODE COUNT 1 AA & MM MASTER FLAG ENT LA-AA AND MM MATSERFLAG AGBABIAKA STR ILOGBO EREMI BADAGRY ERC 1 LA-AA AND MM MATSERFLAG AGUMO MARKET OKOAFO BADAGRY ERC 0 OG-AA AND MM MATSERFLAG BAALE COMPOUND KOFEDOTI LGA ERC 0 2 Abuchi Ed.Ogbuju & Co AB-ABUCHI-ED ST MICHAEL RD ABA ABIA ERC 2 AN-ABUCHI-ED BUILDING MATERIAL OGIDI ERC 2 AN-ABUCHI-ED OGBUJU ZIK AVENUE AWKA ANAMBRA ERC 1 EB-ABUCHI-ED ENUGU BABAKALIKI EXP WAY ISIEKE ERC 0 EN-ABUCHI-ED UDUMA TOWN ANINRI LGA ERC 0 IM-ABUCHI-ED MBAKWE SQUARE ISIOKPO IDEATO NORTH ERC 1 IM-ABUCHI-ED UGBA AFOR OBOHIA RD AHIAZU MBAISE ERC 1 IM-ABUCHI-ED UGBA AMAIFEKE TOWN ORLU LGA ERC 1 IM-ABUCHI-ED UMUNEKE NGOR NGOR OKPALA ERC 0 3 Access Bank Plc DT-ACCESS BANK WARRI SAPELE RD ERC 0 EN-ACCESS BANK GARDEN AVENUE ENUGU ERC 0 FC-ACCESS BANK ADETOKUNBO ADEMOLA WUSE II ERC 0 FC-ACCESS BANK LADOKE AKINTOLA BOULEVARD GARKI II ABUJA ERC 1 FC-ACCESS BANK MOHAMMED BUHARI WAY CBD ERC 0 IM-ACCESS BANK WAAST AVENUE IKENEGBU LAYOUT OWERRI ERC 0 KD-ACCESS BANK KACHIA RD KADUNA ERC 1 KN-ACCESS BANK MURTALA MOHAMMED WAY KANO ERC 1 LA-ACCESS BANK ACCESS TOWERS PRINCE ALABA ONIRU STR ERC 1 LA-ACCESS BANK ADEOLA ODEKU STREET VI LAGOS ERC 1 LA-ACCESS BANK ADETOKUNBO ADEMOLA STR VI ERC 1 LA-ACCESS BANK IKOTUN JUNCTION IKOTUN LAGOS ERC 1 LA-ACCESS BANK ITIRE LAWANSON RD SURULERE LAGOS ERC 1 LA-ACCESS BANK LAGOS ABEOKUTA EXP WAY AGEGE ERC 1 LA-ACCESS -

Design One Project Three Introduced October 21. Due November 11

Design One Project Three Introduced October 21. Due November 11. Typeface Broadside/Poster Broadsides have been an aspect of typography and printing since the earliest types. Printers and Typographers would print a catalogue of their available fonts on one large sheet of paper. The introduction of a new typeface would also warrant the issue of a broadside. Printers and Typographers continue to publish broadsides, posters and periodicals to advertise available faces. The Adobe website that you use for research is a good example of this purpose. Advertising often interprets the type creatively and uses the typeface in various contexts to demonstrate its usefulness. Type designs reflect their time period and the interests and experiences of the type designer. Type may be planned to have a specific “look” and “feel” by the designer or subjective meaning may be attributed to the typeface because of the manner in which it reflects its time, the way it is used, or the evolving fashion of design. For this third project, you will create two posters about a specific typeface. One poster will deal with the typeface alone, cataloguing the face and providing information about the type designer. The second poster will present a visual analogy of the typeface, that combines both type and image, to broaden the viewer’s knowledge of the type. Process 1. Research the history and visual characteristics of a chosen typeface. Choose a typeface from the list provided. -Write a minimum150 word description of the typeface that focuses on two themes: A. The historical background of the typeface and a very brief biography of the typeface designer. -

Atiku Not a Nigerian, Can't Be President, APC Tells Tribunal

SATURDAY No. 688 N300 FOR GOD AND COUNTRY 13.04.19 www.leadership.ng NIGERIA'S MOST INFLUENTIAL NEWSPAPER Leadership Newspapers @leadershipNGA MY SECRET LIFE: RIVERS’ RUNOFF COMMUNITY WHERE MY SPOUSE IS MY ➔ PAGE 71 ELECTION HOLDS TOBACCO IS GOLD PLANNER – JEMIMAH TODAY ➔ PAGE 8 ➔ PAGE 21 Atiku Not A Nigerian, Can’t Be President, APC Tells Tribunal BY KUNLE OLASANMI, Abuja Election Petitions Tribunal in APC said that Atiku, Nigeria’s In a reply to the petition of Atiku should be voided and considered a Abuja, that the candidate of the former vice president between 1999 and the PDP where they prayed for waste by the tribunal. The All Progressives Congress Peoples Democratic Party (PDP) in and 2007, is a Cameroonian and not the declaration of the former vice The APC’s response was (APC), whose candidate, President the poll, Alhaji Atiku Abubakar, is a Nigerian citizen. It, therefore, president as the lawful winner of filed by its lead counsel, Lateef Muhammadu Buhari, won the not a Nigerian and therefore not asked the tribunal to dismiss his the presidential poll, the APC said Fagbemi (SAN), where it faulted February 23, 2019 presidential qualified to have contested in the petition against President Buhari that the 11.1 million votes recorded ➔ CONTINUED ON PAGE 4 election has told the Presidential election. for lack of merit. in favour of the two petitioners Incumbents, Govs-elect At War Over 4 Last-minute Contracts, Appointments They’re plotting to cripple us – Incoming govs We are still in charge, say outgoing govs Governors’ actions fraudulent – Lawyers Military Kills 35 Bandits, Rescues 40 Hostages In Zamfara NAF denies bombing wrong target BY ANKELI EMMANUEL, Sokoto, BY TARKAA DAVID, Abuja The ‘Operation Sharan Daji’ unit of the Nigerian Army in Zamfara State revealed yesterday that it had killed no fewer than 35 bandits, arrested 18 and rescued 40 persons abducted by the bandits. -

Violence in Nigeria's North West

Violence in Nigeria’s North West: Rolling Back the Mayhem Africa Report N°288 | 18 May 2020 Headquarters International Crisis Group Avenue Louise 235 • 1050 Brussels, Belgium Tel: +32 2 502 90 38 • Fax: +32 2 502 50 38 [email protected] Preventing War. Shaping Peace. Table of Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................... i I. Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 1 II. Community Conflicts, Criminal Gangs and Jihadists ...................................................... 5 A. Farmers and Vigilantes versus Herders and Bandits ................................................ 6 B. Criminal Violence ...................................................................................................... 9 C. Jihadist Violence ........................................................................................................ 11 III. Effects of Violence ............................................................................................................ 15 A. Humanitarian and Social Impact .............................................................................. 15 B. Economic Impact ....................................................................................................... 16 C. Impact on Overall National Security ......................................................................... 17 IV. ISWAP, the North West and -

Chieftaincy and Security in Nigeria: the Role of Traditional Institutions

Chieftaincy and Security in Nigeria Past, Present, and Future Edited by Abdalla Uba Adamu ii Chieftaincy and Security in Nigeria Past, Present, and Future Proceedings of the National Conference on Chieftaincy and Security in Nigeria. Organized by the Kano State Emirate Council to commemorate the 40th anniversary of His Royal Highness, the Emir of Kano, Alhaji Ado Bayero, CFR, LLD, as the Emir of Kano (October 1963-October 2003) H.R.H. Alhaji (Dr.) Ado Bayero, CFR, LLD 40th Anniversary (1383-1424 A.H., 1963-2003) Allah Ya Kara Jan Zamanin Sarki, Amin. iii Copyright Pages © ISBN © All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the editors. iv Contents A Brief Biography of the Emir of Kano..............................................................vi Editorial Note........................................................................................................i Preface...................................................................................................................i Opening Lead Papers Chieftaincy and Security in Nigeria: The Role of Traditional Institutions...........1 Lt. General Aliyu Mohammed (rtd), GCON Chieftaincy and Security in Nigeria: A Case Study of Sarkin Kano Alhaji Ado Bayero and the Kano Emirate Council...............................................................14 Dr. Ibrahim Tahir, M.A. (Cantab) PhD (Cantab) -

Islamic Economic Thinking in the 12Th AH/18Th CE Century with Special Reference to Shah Wali-Allah Al-Dihlawi

Munich Personal RePEc Archive Islamic economic thinking in the 12th AH/18th CE century with special reference to Shah Wali-Allah al-Dihlawi Islahi, Abdul Azim Islamic Economics Institute, King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, KSA 2009 Online at https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/75432/ MPRA Paper No. 75432, posted 06 Dec 2016 02:58 UTC Abdul Azim Islahi Islamic Economics Research Center King Abdulaziz University Scientific Publising Center King Abdulaziz University http://spc.kau.edu.sa FOREWORD The Islamic Economics Research Center has great pleasure in presenting th Islamic Economic Thinking in the 12th AH (corresponding 18 CE) Century with Special Reference to Shah Wali-Allah al-Dihlawi). The author, Professor Abdul Azim Islahi, is a well-known specialist in the history of Islamic economic thought. In this respect, we have already published his following works: Contributions of Muslim Scholars to th Economic Thought and Analysis up to the 15 Century; Muslim th Economic Thinking and Institutions in the 16 Century, and A Study on th Muslim Economic Thinking in the 17 Century. The present work and the previous series have filled, to an extent, the gap currently existing in the study of the history of Islamic economic thought. In this study, Dr. Islahi has explored the economic ideas of Shehu Uthman dan Fodio of West Africa, a region generally neglected by researchers. He has also investigated the economic ideas of Shaykh Muhammad b. Abd al-Wahhab, who is commonly known as a religious renovator. Perhaps it would be a revelation for many to know that his economic ideas too had a role in his reformative endeavours. -

Country Travel Risk Summaries

COUNTRY RISK SUMMARIES Powered by FocusPoint International, Inc. Report for Week Ending September 19, 2021 Latest Updates: Afghanistan, Burkina Faso, Cameroon, India, Israel, Mali, Mexico, Myanmar, Nigeria, Pakistan, Philippines, Russia, Saudi Arabia, Somalia, South Sudan, Sudan, Syria, Turkey, Ukraine and Yemen. ▪ Afghanistan: On September 14, thousands held a protest in Kandahar during afternoon hours local time to denounce a Taliban decision to evict residents in Firqa area. No further details were immediately available. ▪ Burkina Faso: On September 13, at least four people were killed and several others ijured after suspected Islamist militants ambushed a gendarme patrol escorting mining workers between Sakoani and Matiacoali in Est Region. Several gendarmes were missing following the attack. ▪ Cameroon: On September 14, at least seven soldiers were killed in clashes with separatist fighters in kikaikelaki, Northwest region. Another two soldiers were killed in an ambush in Chounghi on September 11. ▪ India: On September 16, at least six people were killed, including one each in Kendrapara and Subarnapur districts, and around 20,522 others evacuated, while 7,500 houses were damaged across Odisha state over the last three days, due to floods triggered by heavy rainfall. Disaster teams were sent to Balasore, Bhadrak and Kendrapara districts. Further floods were expected along the Mahanadi River and its tributaries. ▪ Israel: On September 13, at least two people were injured after being stabbed near Jerusalem Central Bus Station during afternoon hours local time. No further details were immediately available, but the assailant was shot dead by security forces. ▪ Mali: On September 13, at least five government soldiers and three Islamist militants were killed in clashes near Manidje in Kolongo commune, Macina cercle, Segou region, during morning hours local time. -

The Theory of Punishment in Islamic Law a Comparative

THE THEORY OF PUNISHMENT IN ISLAMIC LAW A COMPARATIVE STUDY by MOHAMED 'ABDALLA SELIM EL-AWA Thesis submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the University of London, School of Oriental and African Studies, Department of Law March 1972 ProQuest Number: 11010612 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 11010612 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 2 , ABSTRACT This thesis deals with the theory of Punishment in Islamic law. It is divided into four ch pters. In the first chapter I deal with the fixed punishments or Mal hududrl; four punishments are discussed: the punishments for theft, armed robbery, adultery and slanderous allegations of unchastity. The other two punishments which are usually classified as "hudud11, i.e. the punishments for wine-drinking and apostasy are dealt with in the second chapter. The idea that they are not punishments of "hudud11 is fully ex- plained. Neither of these two punishments was fixed in definite terms in the Qurfan or the Sunna? therefore the traditional classification of both of then cannot be accepted. -

325013-Eng.Pdf (602.0Kb)

,I I BIUGIII SMIT PROGNI$S NHllRI illarch 2000 - fG[,2001 SUBilIIIEII MIRGH 20ll1 r0 fi]RrGlil Pn08n[ililt ron ONGilIIGTNGNSF GOilIROl NPllSI For Actica 0ufiGfft0u80u BURmlilm$0 l1 '{{ .,t t., jl t I : .{ 1i KEV @ cATt L.G,n,e ('6, ruofr/ r elit ns. [] SECTION ONE BACKGROUND Bauchi State project is located in the North-East of Nigerian. There are 20 local Govemment Ares in the State. The State shares boundaries with Plateau, Kano, Jigawa, Yobe, Borno, Taraba and Gombe States. The State lies in the Savannah region of Nigeria, with variation in ecological conditions with the southern and western parts being sudan or guinea Savannah, having a relatively higher rainfall, the northern part of the State is sahel Savannah with flat lands and fewer hills. Some major rivers traverse the State. These include the river Hadeja, Jama'are, Gongola and Dindima. Most of the endemic local government areas lies along these river systems. The State has two distinct seasons', dry and rain seasons. There are six months of rain, beginning in May and ending in October. The farming season is from May to December. Most of the onchocerciasis endemic communities are not accessible all year round; the dirt and laterite roads to these communities are usually not motor-able during the height of the rainy season. Even in dry season, where the roads are sandy, four-wheel drive vehicles may be required in some instances along with motorcycles and bicycles. The settlement pattern varies in different part of the State. Generally, there is a pattern of nuclear settlements, with surrounding farmlands. -

Inventory of Existing Rural Water Supply Sources Using Model Nigerian Communities Vis a Vis Household Access to Improved Water

IOSR Journal of Mechanical and Civil Engineering (IOSR-JMCE) e-ISSN: 2278-1684,p-ISSN: 2320-334X, Volume 11, Issue 4 Ver. VII (Jul- Aug. 2014), PP 16-23 www.iosrjournals.org Inventory Of Existing Rural Water Supply Sources Using Model Nigerian Communities Vis a Vis Household Access to Improved Water NDUBUBA, Olufunmilayo I. Civil Engineering Dept. Abubakar Tafawa Balewa University, Bauchi, Nigeria Abstract: A household is considered to have access to basic services required by a family unit in Nigeria if the household has water supply and sanitation facilities, which are used appropriately at all times. A comprehensive inventory of all water sources was conducted in 12 Local Government Areas (LGAs) of four States of Bauchi, Benue, Jigawa and Katsina States between 2011 and 2012; the data was used to relate access to basic services of the people to the population living within the communities studied. It was found that Katsina State had the largest number of solar powered water supply systems (40.3% of all motorized water sources in the State) followed by Bauchi with 36.4%. The most common improved rural water source in the LGAs was bore-holes with hand-pumps (82.28%). Functionality was also monitored. For hand-pumps, there was a relationship between community ownership and functionality (Dass-Bauchi 77.17%; Warji-Bauchi 75.15%; Oju-Benue 82.09%). Population data on each LGA used to analyse the percentage number of household using the improved water sources showed that all the four LGAs still fall short of the basic access of 30 litres per capita per day within 250 metres radius of the water source. -

Statistical Report on Women and Men in Nigeria

2018 STATISTICAL REPORT ON WOMEN AND MEN IN NIGERIA NATIONAL BUREAU OF STATISTICS MAY 2019 i TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS ................................................................................................................ ii PREFACE ...................................................................................................................................... vii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................................................................ ix LIST OF TABLES ....................................................................................................................... xiii LIST OF FIGURES ...................................................................................................................... xv LIST OF ACRONYMS................................................................................................................ xvi CHAPTER 1: POPULATION ....................................................................................................... 1 Key Findings ................................................................................................................................ 1 Introduction ................................................................................................................................. 1 A. General Population Patterns ................................................................................................ 1 1. Population and Growth Rate ............................................................................................ -

Determinants of Utilization of Family Planning Services Among Women of Child-Bearing Age in Rural Areas of Kano State, Northern Nigeria

DETERMINANTS OF UTILIZATION OF FAMILY PLANNING SERVICES AMONG WOMEN OF CHILD-BEARING AGE IN RURAL AREAS OF KANO STATE, NORTHERN NIGERIA BY AMINA ABDULLAHI UMAR MPH/NFELTP/MED/36080/2012-2013 A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO SCHOOL OF POSTGRADUATE STUDIES OF AHMADU BELLO UNIVERSITY, ZARIA IN PART FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE AWARD OF MASTER OF PUBLIC HEALTH (MPH) FIELD EPIDEMIOLOGY AND LABORATORY TRAINING PROGRAMME DEPARTMENT OF COMMUNITY MEDICINE AHMADU BELLO UNIVERSITY, ZARIA NIGERIA JANUARY, 2016 i ATTESTATION I declare that the work in the dissertation titled ―Determinants of utilization of family planning services among women of child-bearing age in rural areas of Kano State, Northern Nigeria‖ was conducted by me in the Department of Community Medicine, Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria under the supervision of Professor Kabir Sabitu And Dr. S.S. Bashir The information derived from the literature has been duly acknowledged. No part of this dissertation was previously presented for another degree or diploma at any university. _____________________ ___________________ Amina Abdullahi Umar Date ii CERTIFICATION I certify that the work for this dissertation titled ―Determinants of utilization of family planning services among women of child bearing age in rural areas of Kano State, Northern Nigeria‖ by Amina Abdullahi Umar meets the regulation governing the award of the degree of Masters of Public Health in Field Epidemiology of Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria and is approved for its contribution to knowledge and literary presentation. ………………………………… ………………………. Professor Kabir Sabitu Date …………………………………. ……………………………….. Dr. S.S. Bashir Date ………………………………… …………………………………. Dr. A.A. Abubakar Date Head, Department of Community Medicine Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria ……………………………….. ………………………………… Prof. Kabir Bala Date The Dean Postgraduate School, Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria iii DEDICATION I dedicate this work to: i.