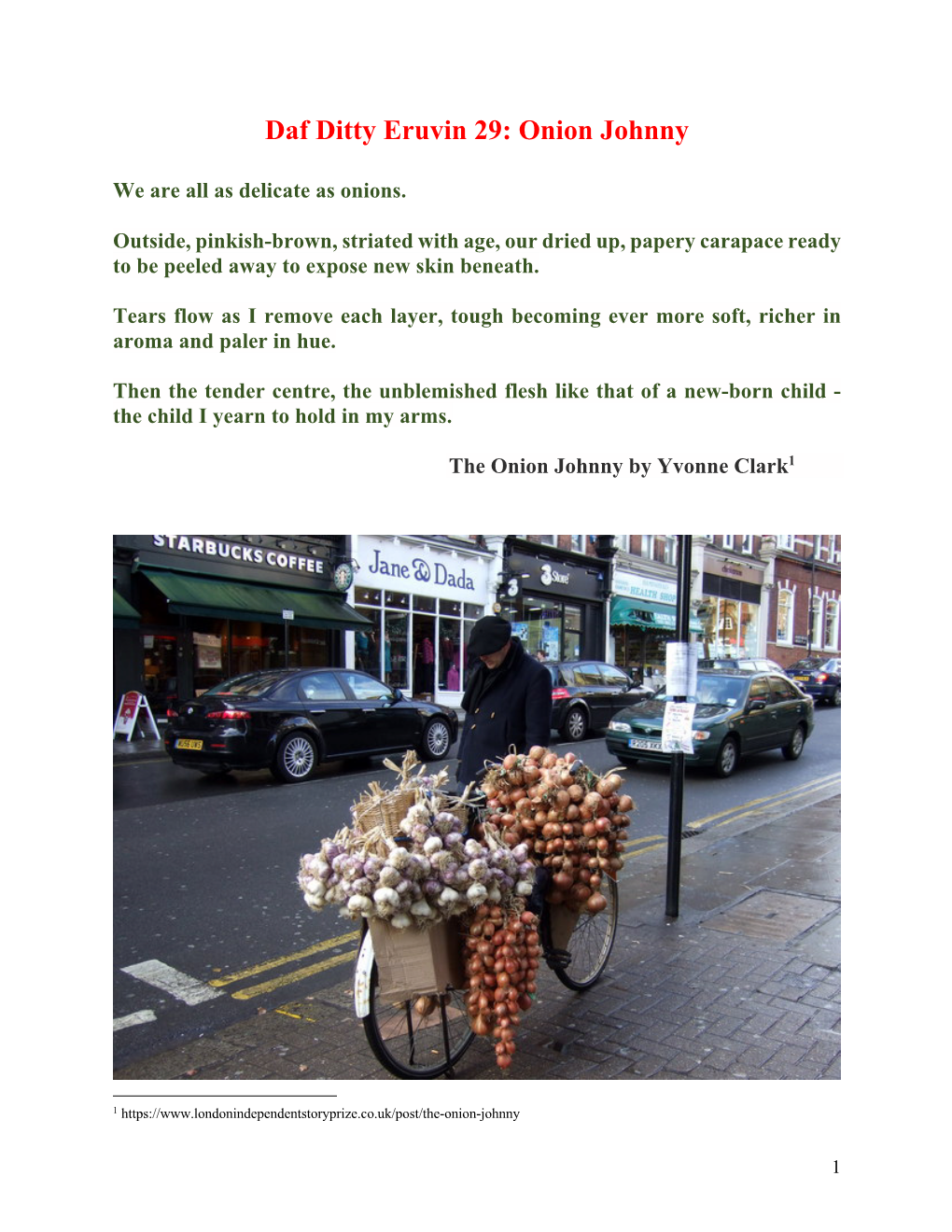

Daf Ditty Eruvin 29- Onion Johnny

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Scottish Studies Society Newsletter

THE SCOTS CANADIAN Issue XLII Newsletter of the Scottish Studies Society: ISSN No. 1491-2759 Spring 2016 Alice Munro named Scot of the Year as 2016 marks the Foundation’s 30th Anniversary It was back in 1986 that the Scottish Studies university of British Columbia Foundation was first established as a and at the University of registered Canadian charity and thanks to the Queensland. support from our members and other donors She married Gerald Fremlin in we are still at work supporting the Scots- 1976 and moved to his Canadian community at the academic level. hometown of Clinton, Ontario, We are delighted that Alice Munro will be not far from Wingham. Gerald helping us to celebrate our 30th anniversary died in April, 2013. Alice has by agreeing to be our Scot of the Year, recently announced her especially shortly after her receiving the retirement from writing and prestigious Nobel Prize in Literature on continues to live in Clinton. December 10, 2013. We are in the process Many of Alice's stories are set of organizing a special event for this special in Huron County, Ontario. Her anniversary and will keep you posted once strong regional focus is one of plans are firmed up. the features of her fiction. Alice Munro: the first Canadian to I’m sure all of you know that Alice is a Another is her frequent use of the receive the Nobel Prize in Literature Canadian short story writer and that her work omniscient narrator who serves has revolutionized the structure of short to make sense of the world. -

Allium Species Poisoning in Dogs and Cats Ticle R

The Journal of Venomous Animals and Toxins including Tropical Diseases ISSN 1678-9199 | 2011 | volume 17 | issue 1 | pages 4-11 Allium species poisoning in dogs and cats TICLE R A Salgado BS (1), Monteiro LN (2), Rocha NS (1, 2) EVIEW R (1) Department of Pathology, Botucatu Medical School, São Paulo State University (UNESP – Univ Estadual Paulista), Botucatu, São Paulo State, Brazil; (2) Department of Veterinary Clinical Sciences, Veterinary Pathology Service, School of Veterinary Medicine and Animal Husbandry, São Paulo State University (UNESP – Univ Estadual Paulista), Botucatu, São Paulo State, Brazil. Abstract: Dogs and cats are the animals that owners most frequently seek assistance for potential poisonings, and these species are frequently involved with toxicoses due to ingestion of poisonous food. Feeding human foodstuff to pets may prove itself dangerous for their health, similarly to what is observed in Allium species toxicosis. Allium species toxicosis is reported worldwide in several animal species, and the toxic principles present in them causes the transformation of hemoglobin into methemoglobin, consequently resulting in hemolytic anemia with Heinz body formation. The aim of this review is to analyze the clinicopathologic aspects and therapeutic approach of this serious toxicosis of dogs and cats in order to give knowledge to veterinarians about Allium species toxicosis, and subsequently allow them to correctly diagnose this disease when facing it; and to educate pet owners to not feed their animals with Allium- containg food in order to better control this particular life-threatening toxicosis. Key words: Allium spp., poisonous plants, hemolytic anemia, Heinz bodies. INTRODUCTION differentiate them from other morphologically similar poisonous plants (6, 7). -

Brasa Food Menu

EVERYTHING ON THE GRILL TO START FROM THE GRILL SIDES Served with a choice of 2 sides & one sauce GRILLED CHICKEN WINGS 8pcs 45 Grilled chicken wings coated in chilli, garlic, honey & lemon served with Brasa hot sauce 1/2 PIRI PIRI CHICKEN 80 FRIED YAM WITH SPICED BUTTER 15 Our marinated chicken in Piri Piri sauce is the spicy love affair between Africa & Portugal SQUID CHILLI & PEPPER 40 FRIED PIRI PIRI CASSAVA 10 Deep fried squid with chilli, garlic & spring onions served with chilli mayo CHICKEN PAILLARD 95 Pounded thin chicken breast, marinated in ginger, garlic & lemon juice FISH CAKE 35 CHOPPED MIXED SALAD 15 Pan fried fish cake with potatoes, garlic, parsley, cassava fish, mustard, lemon & SIRLOIN STEAK 250g 215 smoked tuna served with cherry tomatoes, rocket leaves & parmesan Butter-tender & lean piece of beef with a rim of fat carrying all flavours PARMESAN FRIES 20 USDA graded choice “the best black angus beef since 1939” imported from Aurora Angus Beef, CHILLI PRAWNS 70 from the Midwest, exported by Palmetto for BRASA MIXED GRILLED VEGETABLES 35 Pan fried prawns served with our special chilli tomato sauce & grilled garlic bread PICANHA 250g 185 GRILLED OR FRIED PLANTAIN 15 HUMMUS - BLACK CHICKPEAS 35 Top cut beef, this tender & delecable rump cap is imported from Aurora Angus Beef, A Smooth, thick mix of mashed black chickpeas & tahini from the Midwest, exported by Palmetto for BRASA. USDA graded choice served with sumac, gherkins & bread “the best black angus beef since 1939” CRISPY HALLOUMI & COURGETTE CAKE 50 SALMON 250 A crusty mix of mint, carrot, coriander, spring onions & panko Our Norwegian Salmon marinated in smoked salt & pepper RICE BOWLS served with baked & dried cherry tomatoes, rocket leaves & harissa dressing 45 SALT & PEPPER FISH BAIT 35 COWBOY STEAK for 2 people 560 AFRICAN RICE Chorizo, plantain, green peas & turmeric Deep fried Fish bait in smoked salt & pepper served with Brasa’s special chilli & lemon mayo Served with a choice of 3 sides & 2 sauces Flavourful, rich & juicy steak with a short frenched bone. -

Egyptian Walking Onion.Cdr

HERB HERBERT SPECIAL INTEREST HERBS Herbaceous Perennial Allium cepa var. ‘proliferum’ ESCRIPTION Family: Liliaceae satisfactory. They should be set 5 cm deep about 30 cm apart and Onions and shallots SES are both forms of like a light, rich soil and a sunny Allium cepa and are For culinary purposes, situation similar to all other closely related to Eg yptian Walking Alliums. The small bulbils usually Leeks, Chives, Garlic and Chinese Onions can be used take a year to grow to size before Chives. All these belong to the either cooked or raw. producing top sets of their own. genus Allium and have the They add a wonderful sweet onion They can be harvested alone or the characteristic onion smell, caused flavour to soups, stews and other whole plant lifted and dried like by sulphur compounds, alkyl- cooked meat and vegetable dishes. garlic. Plants should be lifted and sulphides. Use raw or pickled for salads or eat reset in new soil every three years. with bread and cheese or add to an ECIPES The Egyptian Walking Onion also antipasto. Use the leaves as you known as the Tree Onion, grows would chives. Here is a recipe for a from an onion-type bulb simple but delicious producing hollow, round, green A spray made by chopping the flat omelette. leaves and a strong, hollow stem onion bulbs with the skin, and about 50 cm high which, instead mixing with water is said to give FRITTATA DI CIPOLLE of only flowers, produces a cluster some garden plants a resistance to ONION OMELETTE of small bulbils. -

Dictionary of Cultivated Plants and Their Regions of Diversity Second Edition Revised Of: A.C

Dictionary of cultivated plants and their regions of diversity Second edition revised of: A.C. Zeven and P.M. Zhukovsky, 1975, Dictionary of cultivated plants and their centres of diversity 'N -'\:K 1~ Li Dictionary of cultivated plants and their regions of diversity Excluding most ornamentals, forest trees and lower plants A.C. Zeven andJ.M.J, de Wet K pudoc Centre for Agricultural Publishing and Documentation Wageningen - 1982 ~T—^/-/- /+<>?- •/ CIP-GEGEVENS Zeven, A.C. Dictionary ofcultivate d plants andthei rregion so f diversity: excluding mostornamentals ,fores t treesan d lowerplant s/ A.C .Zeve n andJ.M.J ,d eWet .- Wageninge n : Pudoc. -11 1 Herz,uitg . van:Dictionar y of cultivatedplant s andthei r centreso fdiversit y /A.C .Zeve n andP.M . Zhukovsky, 1975.- Me t index,lit .opg . ISBN 90-220-0785-5 SISO63 2UD C63 3 Trefw.:plantenteelt . ISBN 90-220-0785-5 ©Centre forAgricultura l Publishing and Documentation, Wageningen,1982 . Nopar t of thisboo k mayb e reproduced andpublishe d in any form,b y print, photoprint,microfil m or any othermean swithou t written permission from thepublisher . Contents Preface 7 History of thewor k 8 Origins of agriculture anddomesticatio n ofplant s Cradles of agriculture and regions of diversity 21 1 Chinese-Japanese Region 32 2 Indochinese-IndonesianRegio n 48 3 Australian Region 65 4 Hindustani Region 70 5 Central AsianRegio n 81 6 NearEaster n Region 87 7 Mediterranean Region 103 8 African Region 121 9 European-Siberian Region 148 10 South American Region 164 11 CentralAmerica n andMexica n Region 185 12 NorthAmerica n Region 199 Specieswithou t an identified region 207 References 209 Indexo fbotanica l names 228 Preface The aimo f thiswor k ist ogiv e thereade r quick reference toth e regionso f diversity ofcultivate d plants.Fo r important crops,region so fdiversit y of related wild species areals opresented .Wil d species areofte nusefu l sources of genes to improve thevalu eo fcrops . -

Allium Cepa L. Familie Der Liliengewächse (Liliaceae)

Quelle: http://www.mpiz- koeln.mpg.de/oeffentlichkeitsarbeit/kulturpflanzen/Nutzpflanzen/Kuechenzwiebel/index.html Allium cepa L. Familie der Liliengewächse (Liliaceae) links: Entwicklung der Zwiebel: A ein Jahr alt, B älter, rechts: verschiedene Zwiebelsorten Quelle: Rauh,W. Morph. der Nutzpfl., Quelle-Meyer Verlag, Heidelberg 1950; Wolf Garte Verbreitung: Die Küchenzwiebel wird in allen Erdteilen angebaut. Hauptproduktionsländer sind China, Indien, ex-UDSSR, USA, Türkei und Japan. Verlangt Licht, Wärme und nährstoffreiche, nicht zu trockene Böden im neutralen bis alkalischen Herkunft (rot) Anbau (grün) Bereich. Verwendung: Nahrungsmittel (Gewürz, Gemüse, Suppen, Kuchen) Reife Küchenzwiebeln enthalten 85-90 % Wasser, 7-10 % Kohlenhydrate, 1-2 % Eiweiß, 0,25 % Fett; hoher Vitamingehalt. Erträge und Produktion: Produktion (1000 t) Erträge (dt/ha) Land 1979-81 2005 1979-81 2005 China 2650 19050 125 211 India 2550 5500 102 104 USA 1625 36700 344 544 ex-USSR 1940 3870 109 131 Turkey 1020 2000 142 256 UK 223 365 321 324 Welt 21330 57910 132 182 Kultivierung und Züchtung: Die Küchenzwiebel ist eine alte Kulturpflanze der Steppengebiete des west- bis mittelasiatischen Raumes. Die ältesten Berichte über die wirtschaftliche Nutzung von Zwiebeln kommt aus Ägypten. Zwiebeln und Porree bildeten in der Zeit um 2800-2300 v. Chr. einen wichtigen Bestandteil der Nahrung der Pyramidenarbeiter. Mit der römischen Kultur fand die Küchenzwiebel in Europa Verbreitung. Aus dem 15. Jahrhundert liegen Hinweise über den Zwiebelanbau in Holland vor. Es wurden vielfältige Sorten gezüchtet, die sich in Form, Farbe und Geschmack unterscheiden. Als Gewürz werden hellgelbe und bräunlichgelbe, runde Sorten bevorzugt. Für Gemüse finden große, mildschmeckende Sorten Verwendung. Produktionstechnisch unterscheidet man Aussaat von Sommer- und Winterzwiebeln und Steckzwiebelanbau. -

Onion Training Manual 2016

Onion Training Manual 2016 2 Index Page 1. Onion 3 2. Taxonomy and etymology 3-4 3. Desciption 4-5 4. Uses 5-7 5. Nutrients and phytochemicals 8-9 6. Eye irritation 9 7. Cultivation 9-10 8. Pests 10-105 9. Storage in the home 15-16 10. Varieties 16-17 11. Production & trade 17-18 12. References 18-21 13. Regulations 22-30 14. Export colour charts 31-60 15. Sizing Equipment 61 16. Examples of type of packing 62 17. Marking requirements 63 3 Onion The onion (Allium cepa L.) (Latin cepa = onion), also known as the bulb onion or Onion common onion, is a vegetable and is the most widely cultivated species of the genus Allium. This genus also contains several other species variously referred to as onions and cultivated for food, such as the Japanese bunching onion (A. fistulosum), the Egyptian onion (A. ×proliferum), and the Canada onion (A. canadense). The name "wild onion" is applied to a number of Allium species, but A. cepa is exclusively known from cultivation. Its ancestral wild original form is not known, although escapes from cultivation have become established Scientific classification in some regions.[2] The onion is most frequently a biennial or a perennial plant, but is usually treated as Kingdom: Plantae an annual and harvested in its first growing season. Clade : Angiosperms The onion plant has a fan of hollow, bluish•green Clade : Monocots leaves and the bulb at the base of the plant begins to swell when a certain daylength is reached. In the Order: Asparagales autumn, the foliage dies down and the outer layers Family: Amaryllidaceae of the bulb become dry and brittle. -

Banquet and Event Guide

Banquet and Event Guide 1 www.windhammountain.com WHAT’S INSIDE Venues Page 3 & 4 Event Planning Page 5 Event Sample Packages Summer Patio BBQ Page 6 Kids Party Page 6 Bridal & Baby Shower Page 7 Prom & Sweet 16 Page 7 Conference or Weekend Retreat Page 7 Windham Country Club Page 8 Rock’n Mexicana Rehearsal or Welcome Party Page 8 Breakfast Page 9 Lunch Page 10 -12 BBQ Page 13 & 14 Buffet Packages Italian Page 15 Mediterranean Page 16 Rock’n Mexicana Fajita Buffet Page 17 Plated Dinners Page 18 & 19 Hors d’Oeuvres Party Page 20 Specialty Stations & Enhancements Page 21 & 22 Desserts Page 23 Conference and Meeting Breaks Page 24 Windham Country Club Tournament Dining Options Page 25-27 Rock’n Mexicana Welcome Package Page 28 Stations Page 29 Bar Packages Page 30 Mocktails and Cocktails Page 31 Add-On Beer and Wine Options Page 32 Pricing Guide Page 33 Terms and Conditions Page 34 & 35 2 WINDHAM COUNTRY CLUB MULLIGAN’S PUB 3 SUMMIT DECK SEASONS THE PATIO 4 WINWOOD INN UNIQUELY YOURS - EVENTS MADE EASY Event planning is simple with the following easy to book packages. Personalizing your event is our specialty and attention to detail is our passion. From the location selection to the menu options, our event team can guide you through the planning process effortlessly. Host your event: Anniversary Golf Outings and Tournaments After Hours Party Fundraisers Baptism Meet and Greet Party Baby Shower Holiday Party Birthdays – Adults and Kids Retirement Party Bridal Shower Wine Dinners Beer Tasting / Dinners Weddings Conferences Weekend Retreat -

Southern Plant Lists

Southern Plant Lists Southern Garden History Society A Joint Project With The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation September 2000 1 INTRODUCTION Plants are the major component of any garden, and it is paramount to understanding the history of gardens and gardening to know the history of plants. For those interested in the garden history of the American south, the provenance of plants in our gardens is a continuing challenge. A number of years ago the Southern Garden History Society set out to create a ‘southern plant list’ featuring the dates of introduction of plants into horticulture in the South. This proved to be a daunting task, as the date of introduction of a plant into gardens along the eastern seaboard of the Middle Atlantic States was different than the date of introduction along the Gulf Coast, or the Southern Highlands. To complicate maters, a plant native to the Mississippi River valley might be brought in to a New Orleans gardens many years before it found its way into a Virginia garden. A more logical project seemed to be to assemble a broad array plant lists, with lists from each geographic region and across the spectrum of time. The project’s purpose is to bring together in one place a base of information, a data base, if you will, that will allow those interested in old gardens to determine the plants available and popular in the different regions at certain times. This manual is the fruition of a joint undertaking between the Southern Garden History Society and the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation. In choosing lists to be included, I have been rather ruthless in expecting that the lists be specific to a place and a time. -

View Travel Planning Guide

YOUR O.A.T. ADVENTURE TRAVEL PLANNING GUIDE® French Impressions: From the Loire Valley to Lyon & Paris 2021 Small Groups: 8-16 travelers—guaranteed! (average of 13) Overseas Adventure Travel ® The Leader in Personalized Small Group Adventures on the Road Less Traveled 1 Dear Traveler, At last, the world is opening up again for curious travel lovers like you and me. And the O.A.T. French Impressions: From the Loire Valley to Lyon & Paris itinerary you’ve expressed interest in will be a wonderful way to resume the discoveries that bring us so much joy. You might soon be enjoying standout moments like these: I love to see how the people live, work, and play in communities like Angers, a city nestled at the edge of the Loire Valley. When you enjoy a Home-Hosted visit to a local family’s home here, you’ll get an intimate view into what daily life is like in the west of France. You’ll also enjoy a l’apéro, a traditional French social gathering over drinks and regional appetizers, with your hosts. Visiting the village of Oradeur-sur-Glane was a profoundly sobering and saddening experience for me. Four days after the Normandy landings, a German SS company killed all 642 residents of the village and left nothing but devastation in their wake. As I walked the winding lanes of the village with crumbling ruins around me, I felt like I was stuck in time. The atrocities that took place were still on full display so visitors like me can never forget the unthinkable horrors that occured between the Nazis and wartime France. -

Labeled Crops Noted with Days to Harvest (DTH) Crop Subgroups With

INSECTICIDES FOR LEAFMINERS IN ONIONS AND RELATED CROPS THAT MAY BE EFFECTIVE AGAINST ALLIUM LEAFMINER (PHYTOMYZA GYMNOSTOMA) Labeled crops noted with days to harvest (DTH) Crop subgroups with listed crops taken from labels and also found at http://ir4.rutgers.edu/other/CropGroup.htm Trigard (cyromazine): leafminers Not for use in Nassau and Suffolk Counties, NY Bulb Vegetables crop group (7 DTH) Some of the crops in this group are: garlic, great-headed (elephant) garlic, leek, dry bulb onion, green onion, potato onion, tree onion, Welsh onion, rakkyo, and shallot. Scorpion (dinotefuran): for leafminers and others Not for use in NY State Onion, bulb and green (subgroups 3-07A and 3-07B) (1 DTH) Bulb onion, includes: Daylily, bulb; Fritillaria, bulb; Garlic, bulb; Garlic, Great- headed, bulb; Garlic, serpent, bulb; Lily, bulb; Onion, bulb; Onion, Chinese, bulb; Onion; pearl Onion; potato, bulb; Shallot, bulb; Cultivars, varieties and/or, hybrids of these Green onion, includes: Chive, fresh leaves; Chive, Chinese, fresh leaves; Elegans hosta; Fritillaria leaves; Kurrat; Leady’s leek; Leek; Leek, wild; Onion, Beltsville bunching; Onion, fresh; Onion, green; Onion, macrostem; Onion, tree, tops; Onion, Welsh tops; Shallot, fresh leaves; Cultivars, varieties and/or hybrids of these Radiant SC (spinetoram): dipteran leafminers and others Bulb Vegetables (Crop Group 3) (1 DTH) Bulb vegetables: bulb onion, garlic, great-headed (elephant) garlic, green onion, leek, shallot, Welsh onion Herbs (Subgroup 19A) (1 DTH) Includes: chive, chive (Chinese) -

Intoduction to Ethnobotany

Intoduction to Ethnobotany The diversity of plants and plant uses Draft, version November 22, 2018 Shipunov, Alexey (compiler). Introduction to Ethnobotany. The diversity of plant uses. November 22, 2018 version (draft). 358 pp. At the moment, this is based largely on P. Zhukovskij’s “Cultivated plants and their wild relatives” (1950, 1961), and A.C.Zeven & J.M.J. de Wet “Dictionary of cultivated plants and their regions of diversity” (1982). Title page image: Mandragora officinarum (Solanaceae), “female” mandrake, from “Hortus sanitatis” (1491). This work is dedicated to public domain. Contents Cultivated plants and their wild relatives 4 Dictionary of cultivated plants and their regions of diversity 92 Cultivated plants and their wild relatives 4 5 CEREALS AND OTHER STARCH PLANTS Wheat It is pointed out that the wild species of Triticum and related genera are found in arid areas; the greatest concentration of them is in the Soviet republics of Georgia and Armenia and these are regarded as their centre of origin. A table is given show- ing the geographical distribution of 20 species of Triticum, 3 diploid, 10 tetraploid and 7 hexaploid, six of the species are endemic in Georgia and Armenia: the diploid T. urarthu, the tetraploids T. timopheevi, T. palaeo-colchicum, T. chaldicum and T. carthlicum and the hexaploid T. macha, Transcaucasia is also considered to be the place of origin of T. vulgare. The 20 species are described in turn; they comprise 4 wild species, T. aegilopoides, T. urarthu (2n = 14), T. dicoccoides and T. chaldicum (2n = 28) and 16 cultivated species. A number of synonyms are indicated for most of the species.