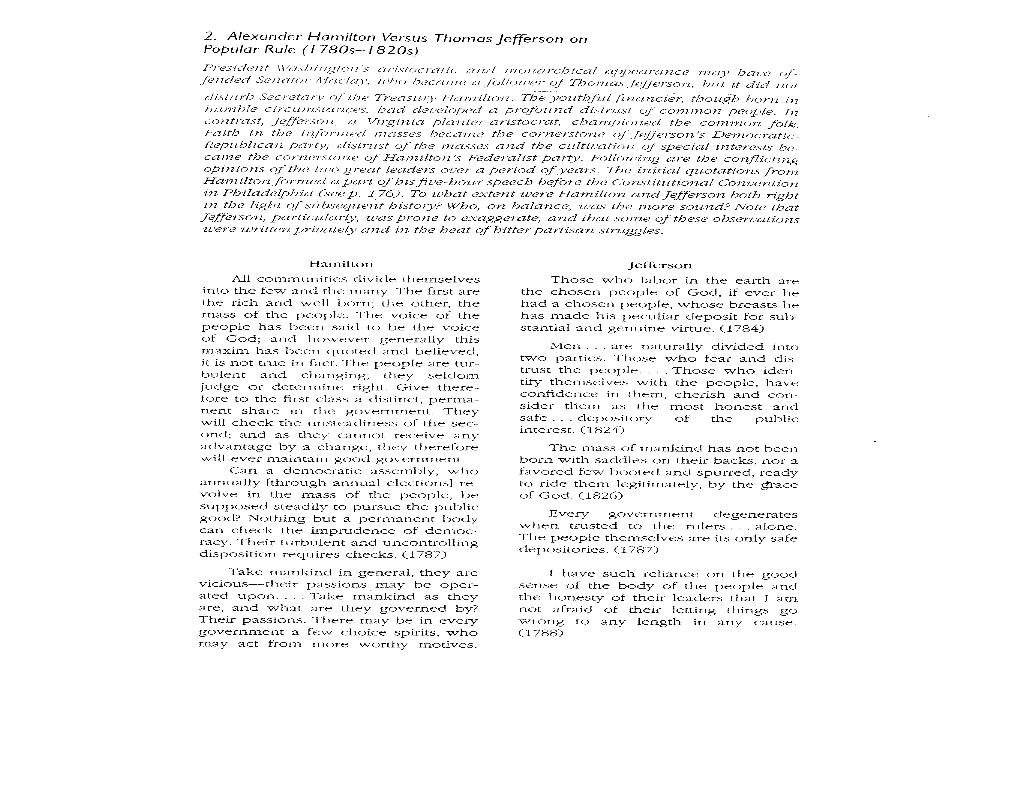

2. Alexander Hamilton Versus Thomasjefferson on Popular Rule

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

780S Series Spray Valves VALVEMATE™ 7040 Controller Operating Manual

780S Series Spray Valves VALVEMATE™ 7040 Controller Operating Manual ® A NORDSON COMPANY US: 888-333-0311 UK: 0800 585733 Mexico: 001-800-556-3484 If you require any assistance or have spe- cific questions, please contact us. US: 888-333-0311 Telephone: 401-434-1680 Fax: 401-431-0237 E-mail: [email protected] Mexico: 001-800-556-3484 UK: 0800 585733 EFD Inc. 977 Waterman Avenue, East Providence, RI 02914-1342 USA Sales and service of EFD Dispense Valve Systems is available through EFD authorized distributors in over 30 countries. Please contact EFD U.S.A. for specific names and addresses. Contents Introduction ..................................................................2 Specifications ..............................................................3 How The Valve and Controller Operate ......................4 Controller Operating Features ....................................5 Typical Setup ..............................................................6 Setup ........................................................................7-8 Adjusting the Spray......................................................9 Programming Nozzle Air Delay ..................................10 Spray Patterns ..........................................................11 Troubleshooting Guide ........................................12-13 Valve Maintenance................................................14-16 780S Exploded View..................................................17 Input / Output Connections..................................18-19 Connecting -

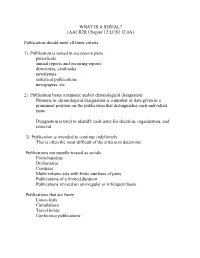

WHAT IS a SERIAL? (AACR2R Chapter 12/LCRI 12.0A)

WHAT IS A SERIAL? (AACR2R Chapter 12/LCRI 12.0A) Publication should meet all three criteria 1) Publication is issued in successive parts periodicals annual reports and recurring reports directories, yearbooks newsletters statistical publications newspapers, etc. 2) Publication bears a numeric and/or chronological designation Numeric or chronological designation is a number or date given in a prominent position on the publication that distinguishes each individual issue Designation is used to identify each issue for check-in, organization, and retrieval 3) Publication is intended to continue indefinitely This is often the most difficult of the criteria to determine Publications not usually treated as serials Encyclopedias Dictionaries Censuses Multi-volume sets with finite numbers of parts Publications of a limited duration Publications revised on an irregular or infrequent basis Publications that are fuzzy Loose-leafs Cumulations Travel books Conference publications KEY POINTS OF SERIALS CATALOGING Base description on first or earliest issue. Every serial record should have a 362 or a 500 Description based on note. New record is created each time the title proper or corporate body (if main entry) changes. (See Serial title changes that require a new record) Cataloging record must represent the entire serial. Bib record must be general enough to apply to the entire serial, but specific enough to cover all access points. Notes are used to show changes in place of publication, publisher, issuing body, frequency, etc. Serial records should never have ISBN numbers for separate issues. Every serial should have a unique title. This is often accomplished with uniform titles. (See Uniform titles) Most serials do not have personal authors. -

Byzantium and Bulgaria, 775-831

Byzantium and Bulgaria, 775–831 East Central and Eastern Europe in the Middle Ages, 450–1450 General Editor Florin Curta VOLUME 16 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.nl/ecee Byzantium and Bulgaria, 775–831 By Panos Sophoulis LEIDEN • BOSTON 2012 Cover illustration: Scylitzes Matritensis fol. 11r. With kind permission of the Bulgarian Historical Heritage Foundation, Plovdiv, Bulgaria. Brill has made all reasonable efforts to trace all rights holders to any copyrighted material used in this work. In cases where these efforts have not been successful the publisher welcomes communications from copyright holders, so that the appropriate acknowledgements can be made in future editions, and to settle other permission matters. This book is printed on acid-free paper. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Sophoulis, Pananos, 1974– Byzantium and Bulgaria, 775–831 / by Panos Sophoulis. p. cm. — (East Central and Eastern Europe in the Middle Ages, 450–1450, ISSN 1872-8103 ; v. 16.) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-90-04-20695-3 (hardback : alk. paper) 1. Byzantine Empire—Relations—Bulgaria. 2. Bulgaria—Relations—Byzantine Empire. 3. Byzantine Empire—Foreign relations—527–1081. 4. Bulgaria—History—To 1393. I. Title. DF547.B9S67 2011 327.495049909’021—dc23 2011029157 ISSN 1872-8103 ISBN 978 90 04 20695 3 Copyright 2012 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands. Koninklijke Brill NV incorporates the imprints Brill, Global Oriental, Hotei Publishing, IDC Publishers, Martinus Nijhoff Publishers and VSP. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, translated, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission from the publisher. -

The Denarius – in the Middle Ages the Basis for Everyday Money As Well

The Denarius – in the Middle Ages the Basis for Everyday Money as well In France the coin was known as "denier," in Italy as "denaro," in German speaking regions as "Pfennig," in England as "penny," – but in his essence, it always was the denarius, the traditional silver coin of ancient Rome. In his coinage reform of the 780s AD, Charlemagne had revalued and reintroduced the distinguished denarius as standard coin of the Carolingian Empire. Indeed for the following 700 years, the denarius remained the major European trade coin. Then, in the 13th century, the Carolingian denarius developed into the "grossus denarius," a thick silver coin of six denarii that was later called "gros," "grosso," "groschen" or "groat." The denarius has lasted until this day – for instance in the dime, the North American 10 cent-coin. But see for yourself. 1 von 15 www.sunflower.ch Frankish Empire, Charlemagne (768-814), Denarius (Pfennig), after 794, Milan Denomination: Denarius (Pfennig) Mint Authority: Emperor Charlemagne Mint: Milan Year of Issue: 793 Weight (g): 1.72 Diameter (mm): 20.0 Material: Silver Owner: Sunflower Foundation The pfennig was the successor to the Roman denarius. The German word "pfennig" and the English term "penny" correspond to the Latin term "denarius" – the d on the old English copper pennies derived precisely from this connection. The French coin name "denier" stemmed from the Latin term as well. This pfennig is a coin of Charlemagne, who in 793/794 conducted a comprehensive reform of the Carolingian coinage. Charlemagne's "novi denarii," as they were called in the Synod of Frankfurt in 794, bore the royal monogram that was also used to authenticate official documents. -

Directory of Commercial Testing and College Research Laboratories

DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE BUREAU OF STANDARDS GEORGE K. BURGESS, Director DIRECTORY OF COMMERCIAL TESTING AND COLLEGE RESEARCH LABORATORIES MISCELLANEOUS PUBLICATION No. 90 BUREAU OF STANDARDS PAMPHLETS ON TESTING There are listed below a few of the official publications of the Bureau of Standards relating to certain phases of testing, including Scientific Papers (S), Technologic Papers (T), Circulars (C), and Miscellaneous Publications (M). Copies of the pamphlets can be obtained, at the prices stated, from the Superintendent of Documents, Government Printing Office, Washington, D. C. In ordering pamphlets from the Superintendent of Documents the bureau publication symbol and number must be stated, and the order must be accompanied by cash. Automobile-tire fabric testing, standardization of, Hose, garden, selection and care of C327. (In T68. Price, 10 cents. press.) Hydrogen sulphide in gas, lead acetate test for, T41. Bags, paper, for cement and lime, a study of test Price, 25 cents. methods for, T187. Price, 5 cents. Hydrometers, testing of, CI 6. Price, 5 cents. Barometers, the testing of, C46. Price, 10 cents. Inks, their composition, Beams, reinforced concrete, shear tests of, T314. manufacture, and methods of testing, C95. Price, 10 Price, 50 cents. cents. Inks, printing, the composition, properties, and test- Bricks, transverse test of, T251. Price, 10 cents. ing of, C53. Price, 10 cents. Bridge columns, large, tests of, T101. Price, 30 cents. Lamp life-testing equipment and methods, recent Cast steel, centrifugally, tests of, T192. Price, 10 developments in, T325. Price, 15 cents. cents. Lamps, incandescent, life testing of, S265. Price, Clay refractories, the testing of, with special refer- 10 cents. -

A Watchman on the Walls: Ezekiel and Reaction to Invasion in Anglo-Saxon England Max K

University of Arkansas, Fayetteville ScholarWorks@UARK Theses and Dissertations 5-2016 A Watchman on the Walls: Ezekiel and Reaction to Invasion in Anglo-Saxon England Max K. Brinson University of Arkansas, Fayetteville Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd Part of the European History Commons, History of Christianity Commons, and the Literature in English, British Isles Commons Recommended Citation Brinson, Max K., "A Watchman on the Walls: Ezekiel and Reaction to Invasion in Anglo-Saxon England" (2016). Theses and Dissertations. 1595. http://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd/1595 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UARK. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UARK. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. A Watchman on the Walls: Ezekiel and Reaction to Invasion in Anglo-Saxon England A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History Max Brinson University of Central Arkansas Bachelor of Arts in History, 2011 University of Central Arkansas Bachelor of Arts in Creative Writing, 2011 May 2016 University of Arkansas This thesis is approved for recommendation to the Graduate Council. Dr. Joshua Smith Thesis Director Dr. Lynda Coon Dr. Charles Muntz Committee Member Committee Member Abstract During the Viking Age, the Christian Anglo-Saxons in England found warnings and solace in the biblical text of Ezekiel. In this text, the God of Israel delivers a dual warning: first, the sins of the people call upon themselves divine wrath; second, it is incumbent upon God’s messenger to warn the people of their extreme danger, or else find their blood on his hands. -

When You Specify Boringly Reliable Fluid Dispense Valve Systems, You Say "Good-Bye" to Costly Downtime

® A NORDSON COMPANY When you specify boringly reliable fluid dispense valve systems, you say "Good-bye" to costly downtime. ® Quiet dependable The best fluid dispense valve system is the one you forget about. EFD precision fluid dispense valves eliminate or significantly reduce production downtime costs. When maintenance is required, simplified procedures mean minimal interruption. EFD dispense valves—maximum reliability with the lowest "fuss" factor. Engineered for the most demanding mechanical and envi- ronmental applications, EFD valve systems provide very reliable dispensing solutions for benchtop applications, machine builders, and very cost-effective, drop-in retrofit alternatives for machine operators. Index Valve features and selector — pages 4 to 5 Dispense valves — pages 6 to 27 diaphragm, piston, high flow, needle, high pressure, spray, internal spray, coating, auger Applications — pages 28 to 29 Valve controllers — pages 30 to 35 VALVEMATE™ 7000 and controllers for spray, internal spray and auger systems 735HPA spool valve applies even stripes of structural adhesive to brake shoe linings. Fluid reservoirs — page 36 2.5 oz. cartridges, one liter and 5.0 liter tanks Fuel injection manifold bores on Ford engines receive a fine coating of oil without overspray Dispensing tips — page 37 by using 780S-SS spray valves. photo courtesy of Ford Motor Company Recommendations — page 39 Fine flow control of the 752V-SS diaphragm valve evenly coats compact disc with UV-cure lacquer. photo courtesy of Weld-Equip Europe 2 dispense valve systems Proof of performance Before you commit to EFD dispense valve systems, you want to thoroughly prove the value of this change. EFD will provide at no cost a complete evaluation system for your testing—valve, controller and tank reservoir. -

Propositiones Ad Acuendos Iuvenes

‘ECCE FABULA!’ PROBLEM-SOLVING BY NUMBERS IN THE CAROLINGIAN WORLD: THE CASE OF THE PROPOSITIONES AD ACUENDOS IUVENES BY RUTGER KRAMER Austrian Academy of Sciences 'Ich habe bemerkt', sagte Herr K., 'daß wir viele abschrecken von unserer Lehre dadurch, daß wir auf alles eine Antwort wissen. Könnten wir nicht im Interesse der Propaganda eine Liste der Fragen aufstellen, die uns ganz ungelöst 1 erscheinen?' Sometime in the mid-780s, Charlemagne, King of the Franks, had a letter composed in his name, and sent it to all of the abbots and bishops in his realm. His goals were as ambitious as they were reflective of a basic need to reinvigorate the pursuit of knowledge among his prelates. To start this endeavour, the letter states, it was vital to make sure that education in the realm was up to par: For although correct conduct may be better than knowledge, 1 Bertolt Brecht, Geschichten vom Herrn Keuner (Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp, 1971), ll. 239-43 ['"I have noticed", said Mr. K., "that we put many people off our teaching because we have an answer to everything. Could we not, in the interests of propaganda, draw up a list of questions that appear to us completely unsolved?"', Stories of Mr. Keuner, trans. by Martin Chalmers (San Francisco: City Lights Books, 2001), p. 18]. 16 Rutger Kramer nevertheless knowledge precedes conduct. Therefore, everyone ought to study what he desires to accomplish, so that so much the more fully the mind may know what ought to be done, as the tongue hastens in the praises of omnipotent God without the hindrances of errors. -

Christian Apostate Literature in Medieval Islam Dissertation

Voices of the Converted: Christian Apostate Literature in Medieval Islam Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Clint Hackenburg, M.A. Graduate Program in Near Eastern Languages and Cultures The Ohio State University 2015 Dissertation Committee: Kevin van Bladel, Advisor Bilal Orfali Hadi Jorati Copyright by Clint Hackenburg 2015 Abstract This dissertation seeks to discuss the dialectical (kalām) and scriptural (both biblical and qurʾānic) reasoning used to justify Christian conversion to Islam during the medieval period (750 - 1492 C.E.). With this objective in mind, I will compare and contrast the manners in which five different Arabophone authors, ʿAlī ibn Sahl Rabban al-Ṭabarī (d. ca. 860), al-Ḥasan ibn Ayyūb (fl. ca. mid-tenth century), Naṣr ibn Yaḥyā (d. 1163 or 1193), Yūsuf al-Lubnānī (d. ca mid-thirteenth century), and Anselm Turmeda (d. 1423), all Christian converts to Islam, utilized biblical and qurʾānic proof-texts alongside dialectical reasoning to invalidate the various tenets of Christianity while concurrently endorsing Islamic doctrine. These authors discuss a wide variety of contentious issues pervading medieval Christian-Muslim dialogue. Within the doctrinal sphere, these authors primarily discuss the Trinity and Incarnation, the nature of God, and the corruption of the Bible (taḥrīf). Within the exegetical realm, these authors primarily discussed miracles, prophecy, and prophetology. Moreover, this dissertation seeks to discern how these authors and their works can be properly contextualized within the larger framework of medieval Arabic polemical literature. That is to say, aside from parallels and correspondences with one another, what connections, if any, do these authors have with other contemporary Arabophone Muslim, Christian, and, to a lesser extent, Jewish apologists and polemicists? ii In the course of my research on Christian apostate literature, I have come to two primary conclusions. -

Charlemagne's Health In

applyparastyle “fig//caption/p[1]” parastyle “FigCapt” Mediaevistik 32 . 2019 11 2020 Bernard S. Bachrach 00 Charlemagne’s Health in ‘Old Age’: Did It Affect Carolingian Military Strategy? 00 11 During the first thirty-three years of his reign as king of the Franks, i.e., prior to his 54 coronation as emperor on Christmas day 800, Charlemagne, scholars generally agree, pursued a successful long-term offensive and expansionist strategy. This strategy was 2020 aimed at conquering large swaths of erstwhile imperial territory in the west and brin- ging under Carolingian rule a wide variety of peoples, who either themselves or their regional predecessors previously had not been subject to Frankish regnum.1 For a very long time, scholars took the position that Charlemagne continued to pursue this expan- sionist strategy throughout the imperial years, i.e., from his coronation on Christmas Day 800 until his final illness in later January 814. For example, Louis Halphen obser- ved: “comme empereur, Charles poursuit, sans plus, l’oeuvre entamée avant l’an 800.”2 F. L. Ganshof, who also wrote several studies treating Charlemagne’s army, was in lock step with Halphen and observed: “As emperor, Charlemagne pursued the political and military course he had been following before 25 December 800.”3 In a similar vein, Ferdinand Lot made clear that Charlemagne continued his previ- ous expansionist war aims and divided the responsibilities for carrying out his impe- rial strategy of expansion among his three sons. Lot observed: “Il laisse ce soin à ses fils: Charles, l’ainé, lutte contre les Slaves; Pépin, roi d’Italie, contra les Avars...; Louis bataille dans la Marche d’Espagne. -

(AD 700–900) Occupation of Ridges Basin, Southwest Colorado

Research Article Chronostratigraphic and Paleoenvironmental Evidence for Marsh Habitats during the Early Pueblo I (A.D. 700–900) Occupation of Ridges Basin, Southwest Colorado, USA Kirk C. Anderson1,* and James M. Potter2 1Museum of Northern Arizona, Flagstaff, Arizona 2PaleoWest Archaeology, Pasadena, California Correspondence Ridges Basin was home to one of the largest early village communities in the *Corresponding author; E-mail: American Southwest. The short-lived occupation grew rapidly around A.D. [email protected] 750, construction peaked in the A.D. 780s, but Ridges Basin was depopu- Received lated by A.D. 810. Chronostratigraphic, paleoenvironmental, and archaeologi- 5 December 2012 cal investigations indicate that abundant food resources related to intermittent Revised marsh habitats attracted migrants into the basin and aided the growing popula- 9 November 2014 tion. Extreme droughts between A.D. 795 and 809 led to decreased crop yields Accepted and marsh desiccation. We attribute the abrupt depopulation of Ridges Basin 28 November 2014 to declining environmental conditions and societal stresses. We describe the Scientific editing by Vance Holliday impact of marsh formation on the inhabitants, and explore the wider impli- cations of marshes and reservoirs on the Puebloan landscape. We suggest that Published online in Wiley Online Library early Puebloans positioned their settlements in proximity to natural marshes (wileyonlinelibrary.com). to take advantage of the abundant plant and animal resources, which later Puebloans achieved through the construction of reservoirs. C 2015 Wiley Pe- doi 10.1002/gea.21503 riodicals, Inc. INTRODUCTION 1997). Most of these features are associated with large settlements dating to the Pueblo II and Pueblo III peri- The American Southwest is well known for its gener- ods (A.D. -

Appropriations of the Master's Legacy

Appropriations Of The Master’s Legacy 167 Chapter 5 Appropriations of the Master’s Legacy Just enough evidence survives in the textual record of the eighth, ninth, and tenth centuries to enable us not only to document the transformation of Wang Tong’s legacy over this span of time, but to glimpse its progress in stages. As the previous chapter revealed, the crafting of Master Wenzhong’s image in the sev- enth century was essentially a family project of the Wangs, who hallowed their ancestor for his Confucius-like comportment and convictions and his tireless crusade to restore the classical ideals and teachings of the ancient sage kings. We saw also that by the time of Lu Guimeng’s “Preface to a Letter Sent with Mr. Doulu,” written in the late ninth century and quoted at the chapter’s close, Wang Tong’s name had to some extent entered into general currency and the terms of his praises had expanded. Several late Tang and early Song texts will hereaf- ter complete the available picture, by showing how in certain men’s minds Wang Tong merited veneration, if not official canonization, as a divinely sent Confucian Worthy. Through his putative tutelage of the ablest ministers at Taizong’s court, they also reasoned, Wang Tong was nothing less than the intel- lectual father of the Tang Dynasty. The present chapter traces the process of this transformation and interprets its implications for our understanding of the tex- tual history of the Zhongshuo. The pivotal historical event in this story, as it is of Tang history generally, is the An Lushan rebellion of the mid-eighth century (755–763), after which the empire never recovered its former stability let alone the former reach of its administrative control.