Charlemagne's Health In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nachruf Prof. Dr. Eugen Ewig

322 Nachrufe Eugen Ewig 18.5.1913 – 1.3.2006 Im hohen Alter, im 93. Lebensjahr, starb Eugen Ewig am 1. März 2006, einer der international angesehensten Mediävisten; er war seit 1979 korrespondierendes Mit- glied der Bayerischen Akademie der Wis- senschaften. 1913 in Bonn geboren, besuchte er das humanistische Beethoven-Gymnasium und studierte in seiner Heimatstadt von 1931– 1937 Geschichte und zuletzt Romanistik, vornehmlich bei Wilhelm Levison und Ernst Robert Curtius. Mit Curtius hat bereits viel zu tun, was Ewigs späteres Wirken nachhaltig kennzeichnete: „Eine auf- keimende Neigung zu Frankreich hat er gefestigt, mein Frankreichbild hat er geprägt und durch die Schärfung des Blicks für Zusammenhänge mit der geistigen Tradition der Antike und der lateinischen Literatur vertieft“ (Ewig in seiner Erwiderung auf seine Wahl in die Rheinisch-Westfälische Akademie der Wissenschaften 1978; die Laudatio hielt Theodor Schief- fer: Jahrbuch 1978 der Akademie, S. 63). Von Levison, seinem jüdischen, 1935 aus dem Amt gedrängten Lehrer, erhielt Ewig als sein letzter Schüler noch sein Dissertationsthema, wurde von ihm auch betreut, doch für die Prüfungsformalien musste Anfang 1936 bereits der Neuhistoriker Max Braubach einspringen. Ewig hatte Levison stets die Treue gehalten und ihn auch bei seiner späten Ausreise nach England in mutiger, für ihn selbst gefährlicher Weise unterstützt. Das Dissertationsthema, das der Altmeister Levison Ewig anvertraute, handelte über einen Autor des 15. Jahrhunderts: „Die Anschauungen des Karthäusers Dionysius von Roermond über den christlichen Ordo in Staat und Kirche“, erschienen 1936. Aus gesundheitlichen Gründen vom Militär freigestellt, als liberaler Geist, als überzeugter Katholik und ohne jede Bindung an die NSDAP waren etwaige Gedanken an eine Hochschullaufbahn obsolet. -

780S Series Spray Valves VALVEMATE™ 7040 Controller Operating Manual

780S Series Spray Valves VALVEMATE™ 7040 Controller Operating Manual ® A NORDSON COMPANY US: 888-333-0311 UK: 0800 585733 Mexico: 001-800-556-3484 If you require any assistance or have spe- cific questions, please contact us. US: 888-333-0311 Telephone: 401-434-1680 Fax: 401-431-0237 E-mail: [email protected] Mexico: 001-800-556-3484 UK: 0800 585733 EFD Inc. 977 Waterman Avenue, East Providence, RI 02914-1342 USA Sales and service of EFD Dispense Valve Systems is available through EFD authorized distributors in over 30 countries. Please contact EFD U.S.A. for specific names and addresses. Contents Introduction ..................................................................2 Specifications ..............................................................3 How The Valve and Controller Operate ......................4 Controller Operating Features ....................................5 Typical Setup ..............................................................6 Setup ........................................................................7-8 Adjusting the Spray......................................................9 Programming Nozzle Air Delay ..................................10 Spray Patterns ..........................................................11 Troubleshooting Guide ........................................12-13 Valve Maintenance................................................14-16 780S Exploded View..................................................17 Input / Output Connections..................................18-19 Connecting -

Pariser Historische Studien Bd. 86 2007

Pariser Historische Studien Bd. 86 2007 Copyright Das Digitalisat wird Ihnen von perspectivia.net, der Online-Publi- kationsplattform der Max Weber Stiftung – Deutsche Geisteswis- senschaftliche Institute im Ausland, zur Verfügung gestellt. Bitte beachten Sie, dass das Digitalisat urheberrechtlich geschützt ist. Erlaubt ist aber das Lesen, das Ausdrucken des Textes, das Her- unterladen, das Speichern der Daten auf einem eigenen Datenträ- ger soweit die vorgenannten Handlungen ausschließlich zu priva- ten und nicht-kommerziellen Zwecken erfolgen. Eine darüber hi- nausgehende unerlaubte Verwendung, Reproduktion oder Weiter- gabe einzelner Inhalte oder Bilder können sowohl zivil- als auch strafrechtlich verfolgt werden. Eugen Ewig REINHOLD KAISER EUGENEWIG Vom Rheinland zum Abendland Eugen Ewig ist am 18. März 1913 in Bonn geboren und in Bonn am 1. März 2006 mit fast 93 Jahren gestorben. Er gehört zu jenen rheinischen und katholi schen Historikern, die durch ihr Wirken in Universität, Forschung, Politik und Öffentlichkeit die Frühmittelalterforschung in Deutschland nachhaltig be stimmt haben. Sein wissenschaftliches CEuvre ist in einem Zeitraum von 70 Jahren zwischen 1936 und 2006 entstanden '. Er zählt angesichts seines um- I Eine kurze Würdigung von Leben und Werk Eugen Ewigs findet sich im Geleitwort von Karl Ferdinand WERNER zu den beiden vom Deutschen Historischen Institut Paris publi zierten Sammelbänden von Hartmut ATSMA (Hg.), Eugen Ewig, Spätantikes und fränki• sches Gallien. Gesammelte Schriften (1952-1973), 2 Bde., Zürich, München 1976-1979 (Beihefte der Francia, 3/1-2), Bd. 1, S. IX-XII; knapp ist das Vorwort von Rudolf SCHIEFFER in: DERS. (Hg.), Beiträge zur Geschichte des Regnum Francorum. Referate beim Wissenschaftlichen Colloquium zum 75. Geburtstag von Eugen Ewig am 28. -

Boar Hunting Weapons of the Late Middle Ages and Renaissance Doug Strong

Boar Hunting Weapons of the Late Middle Ages and Renaissance Doug Strong When one thinks of weapons for hunting, two similar devices leap to mind, the bow and the crossbow. While it is true that these were used extensively by hunters in the middle ages and the renaissance they were supplemented by other weapons which provided a greater challenge. What follows is an examination of the specialized tools used in boar hunting, from about 1350- 1650 CE. It is not my intention to discuss the elaborate system of snares, pits, nets, and missile weapons used by those who needed to hunt but rather the weapons used by those who wanted to hunt as a sport. Sport weapons allowed the hunters to be in close proximity to their prey when it was killed. They also allowed the hunters themselves to pit their own strength against the strength of a wild boar and even place their lives in thrilling danger at the prospect of being overwhelmed by these wild animals. Since the dawn of time mankind has engaged in hunting his prey. At first this was for survival but later it evolved into a sport. By the middle ages it had become a favorite pastime of the nobility. It was considered a fitting pastime for knights, lords, princes and kings (and later in this period, for ladies as well!) While these people did not need to provide the game for their tables by their own hand, they had the desire to participate in an exciting, violent, and even dangerous sport! For most hunters two weapons were favored for boar hunting; the spear and the sword. -

Bulletin Du Centre D'études Médiévales

Bulletin du centre d’études médiévales d’Auxerre | BUCEMA 22.1 | 2018 Varia Alsace and Burgundy : Spatial Patterns in the Early Middle Ages, c. 600-900 Karl Weber Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/cem/14838 DOI: 10.4000/cem.14838 ISSN: 1954-3093 Publisher Centre d'études médiévales Saint-Germain d'Auxerre Electronic reference Karl Weber, « Alsace and Burgundy : Spatial Patterns in the Early Middle Ages, c. 600-900 », Bulletin du centre d’études médiévales d’Auxerre | BUCEMA [Online], 22.1 | 2018, Online since 03 September 2018, connection on 19 April 2019. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/cem/14838 ; DOI : 10.4000/ cem.14838 This text was automatically generated on 19 April 2019. Les contenus du Bulletin du centre d’études médiévales d’Auxerre (BUCEMA) sont mis à disposition selon les termes de la Licence Creative Commons Attribution - Pas d’Utilisation Commerciale - Partage dans les Mêmes Conditions 4.0 International. Alsace and Burgundy : Spatial Patterns in the Early Middle Ages, c. 600-900 1 Alsace and Burgundy : Spatial Patterns in the Early Middle Ages, c. 600-900 Karl Weber EDITOR'S NOTE Cet article fait référence aux cartes 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 8 et 10 du dossier cartographique. Ces cartes sont réinsérées dans le corps du texte et les liens vers le dossier cartographique sont donnés en documents annexes. Bulletin du centre d’études médiévales d’Auxerre | BUCEMA, 22.1 | 2018 Alsace and Burgundy : Spatial Patterns in the Early Middle Ages, c. 600-900 2 1 The following overview concerns the question of whether forms of spatial organisation below the kingdom level are discernible in the areas corresponding to present-day Western Switzerland and Western France during the early Middle Ages. -

Chronik Des Akademischen Jahres 2005/2006

CHRONIK DES AKADEMISCHEN JAHRES 2005/2006 Chronik des Akademischen Jahres 2005/2006 herausgegeben vom Rektor der Rheinischen Friedrich-Wilhelms- Universität Bonn, Prof. Dr. Matthias Winiger, Bonn 2006. Redaktion: Jens Müller, Archiv der Universität Bonn Herstellung: Druckerei der Universität Bonn MATTHIAS WINIGER RHEINISCHE FRIEDRICH-WILHELMS-UNIVERSITÄT BONN Chronik des Akademischen Jahres 2005/06 Bonn 2006 Jahrgang 121 Neue Folge Jahrgang 110 INHALTSVERZEICHNIS Rede des Rektors zur Eröffnung des Akademischen Jahres Rückblick auf das Akademische Jahr 2005/06 .....S. 9 Preisverleihungen und Ehrungen Preisverleihungen und Ehrungen im Akademischen Jahr 2005/06 ...........................S. 23 Akademischer Festvortrag Wilhelm Barthlott, Biodiversität als Herausforderung und Chance.................................S. 25 Chronik des Akademischen Jahres Das Akademische Jahr 2005/06 in Pressemeldungen..............................................S. 40 Nachrufe ......................................................................S. 54 Berichte aus den Fakultäten Evangelisch-Theologische Fakultät ....................S. 67 Katholisch-Theologische Fakultät ......................S. 74 Rechts- und Staatswissenschaftliche Fakultät S. 83 Medizinische Fakultät ............................................S. 103 Philosophische Fakultät .........................................S. 134 Mathematisch-Naturwissenschaftliche Fakultät.......S. 170 Landwirtschaftliche Fakultät ..................................S. 206 Beitrag zur Universitätsgeschichte Thomas Becker, -

Hunting and Social Change in Late Saxon England

Eastern Illinois University The Keep Masters Theses Student Theses & Publications 2016 Butchered Bones, Carved Stones: Hunting and Social Change in Late Saxon England Shawn Hale Eastern Illinois University This research is a product of the graduate program in History at Eastern Illinois University. Find out more about the program. Recommended Citation Hale, Shawn, "Butchered Bones, Carved Stones: Hunting and Social Change in Late Saxon England" (2016). Masters Theses. 2418. https://thekeep.eiu.edu/theses/2418 This is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Theses & Publications at The Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of The Keep. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Graduate School� EASTERNILLINOIS UNIVERSITY " Thesis Maintenance and Reproduction Certificate FOR: Graduate Candidates Completing Theses in Partial Fulfillment of the Degree Graduate Faculty Advisors Directing the Theses RE: Preservation, Reproduction, and Distribution of Thesis Research Preserving, reproducing, and distributing thesis research is an important part of Booth Library's responsibility to provide access to scholarship. In order to further this goal, Booth Library makes all graduate theses completed as part of a degree program at Eastern Illinois University available for personal study, research, and other not-for-profit educational purposes. Under 17 U.S.C. § 108, the library may reproduce and distribute a copy without infringing on copyright; however, professional courtesy dictates that permission be requested from the author before doing so. Your signatures affirm the following: • The graduate candidate is the author of this thesis. • The graduate candidate retains the copyright and intellectual property rights associated with the original research, creative activity, and intellectual or artistic content of the thesis. -

Das Gebiet Des Nördlichen Mittelrheins Als Teil Der Germania Prima in Spätrömischer Und Frühmittelalterlicher Zeit

Das Gebiet des nördlichen Mittelrheins als Teil der Germania prima in spätrömischer und frühmittelalterlicher Zeit VON FRANZ-JOSEF HEYEN Mein Part in den Verhandlungen bestand darin, die Umrisse des Geschehens am nördli chen Mittelrhein in der Spätantike und im frühen Mittelalter zu schildern. Selbstver ständlich kann das auch zwischen dem vorangegangenen großen Überblick von Eu gen Ewig und den nachfolgenden, speziell einzelnen Orten gewidmeten Referaten nur ein weitestgehend auf der vorhandenen Literatur 0 aufbauendes grobes Raster sein, in dem lediglich in einigen Feldern Akzente oder Fragezeichen gesetzt oder auch neue An sätze zur Diskussion gestellt werden können. Schon die räumliche Umschreibung des Untersuchungsgebietes als »nördlicher Mit telrhein« ist umständlich, weil ein umfassender Landschaftsname fehlt. Aber offensicht lich ist dies schon eine, auch für die historische Betrachtung wichtige Beobachtung, macht sie doch deutlich, daß dem Raum einerseits ein beherrschendes, namengebendes Oberzentrum oder Landschaftsgefüge fehlt, er aber anderseits von den Nachbarräumen nicht abgedeckt, sondern ausgespart wird, sozusagen übrig bleibt. Zumindest bietet sich auf den ersten Blick dieses Bild, und auch bei der Durchmusterung der Literatur wird man bald feststellen, daß dieser Raum meist nur »am Rande« behandelt wurde. Wir werden die Frage präsent zu halten haben, ob dies eine Feststellung ist, die zur Charak terisierung des Raumes als historisches Gebilde geeignet ist und zwar kontinuierlich oder nur in bestimmten Epochen und welche Folgerungen dies für den Ablauf des hi storischen Geschehens haben müßte und hatte. Angesprochen ist das Rheintal mit den beidseits angrenzenden Gebieten zwischen Andernach/Sinzig im Norden und Oberwesel/Bingen im Süden bzw. zwischen den Mündungen von Ahr und Nahe, das unmittelbare Einzugsgebiet beider Flüsse jeweils ausgeschlossen. -

The Hunt in Romance and the Hunt As Romance

THE HUNT IN ROMANCE AND THE HUNT AS ROMANCE A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Jacqueline Stuhmiller May 2005 © 2005 Jacqueline Stuhmiller THE HUNT IN ROMANCE AND THE HUNT AS ROMANCE Jacqueline Stuhmiller, Ph. D. Cornell University 2005 This dissertation examines the English and French late medieval hunting manuals, in particular Gaston Phébus’ Livre de chasse and Edward of Norwich’s Master of Game. It explores their relationships with various literary and nonliterary texts, as well as their roles in the late medieval imagination, aristocratic self-image, and social economy. The medieval aristocracy used hunting as a way to imitate the heroes of chivalric romance, whose main pastimes were courtly love, arms, and the chase. It argues that manuals were, despite appearances, works of popular and imagination-stimulating literature into which moral or practical instruction was incorporated, rather than purely didactic texts. The first three chapters compare the manuals’ content, style, authorial intent, and reader reception with those of the chivalric romances. Both genres are concerned with the interlaced adventures of superlative but generic characters. Furthermore, both genres are popular, insofar as they are written for profit and accessible to sophisticated and unsophisticated readers alike. The following four chapters examine the relationships between hunting, love, and military practices and ethics, as well as those between their respective didactic literatures. Hunters, dogs, and animals occupied a sort of interspecific social hierarchy, and the more noble individuals were expected to adhere to a code of behavior similar to the chivalric code. -

The Viking Winter Camp of 872-873 at Torskey, Lincolnshire

Issue 52 Autumn 2014 ISSN 1740 – 7036 Online access at www.medievalarchaeology.org NEWSLETTER OF THE SOCIETY FOR MEDIEVAL ARCHAEOLOGY Contents Research . 2 Society News . 4 News . 6 Group Reports . 7 New Titles . 10 Media & Exhibitions . 11 Forthcoming Events . 12 The present issue is packed with useful things and readers cannot but share in the keen current interest in matters-Viking. There are some important game-changing publications emerging and in press, as well as exhibitions, to say nothing of the Viking theme that leads the Society's Annual Conference in December. The Group Reports remind members that the medieval world is indeed bigger, while the editor brings us back to earth with some cautious observations about the 'quiet invasion' of Guidelines. Although shorter than usual, we look forward to the next issue being the full 16 pages, when we can expect submissions about current research and discoveries. The Viking winter camp Niall Brady Newsletter Editor of 872-873 at Torskey, e-mail: [email protected] Left: Lincolnshire Geophysical survey at Torksey helps to construct the context for the individual artefacts recovered from the winter camp new archaeological discoveries area. he annual lecture will be delivered this (micel here) spent the winter at Torksey Tyear as part of the Society’s conference, (Lincolnshire). This brief annal tells us which takes place in Rewley House, Oxford little about the events that unfolded, other (5th-7th December) (p. 5 of this newsletter), than revealing that peace was made with and will be delivered by the Society’s the Mercians, and even the precise location Honorary Secretary, Prof. -

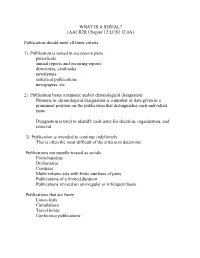

WHAT IS a SERIAL? (AACR2R Chapter 12/LCRI 12.0A)

WHAT IS A SERIAL? (AACR2R Chapter 12/LCRI 12.0A) Publication should meet all three criteria 1) Publication is issued in successive parts periodicals annual reports and recurring reports directories, yearbooks newsletters statistical publications newspapers, etc. 2) Publication bears a numeric and/or chronological designation Numeric or chronological designation is a number or date given in a prominent position on the publication that distinguishes each individual issue Designation is used to identify each issue for check-in, organization, and retrieval 3) Publication is intended to continue indefinitely This is often the most difficult of the criteria to determine Publications not usually treated as serials Encyclopedias Dictionaries Censuses Multi-volume sets with finite numbers of parts Publications of a limited duration Publications revised on an irregular or infrequent basis Publications that are fuzzy Loose-leafs Cumulations Travel books Conference publications KEY POINTS OF SERIALS CATALOGING Base description on first or earliest issue. Every serial record should have a 362 or a 500 Description based on note. New record is created each time the title proper or corporate body (if main entry) changes. (See Serial title changes that require a new record) Cataloging record must represent the entire serial. Bib record must be general enough to apply to the entire serial, but specific enough to cover all access points. Notes are used to show changes in place of publication, publisher, issuing body, frequency, etc. Serial records should never have ISBN numbers for separate issues. Every serial should have a unique title. This is often accomplished with uniform titles. (See Uniform titles) Most serials do not have personal authors. -

DOGS in MEDIEVAL ART Text and Illustrations by RIA HÖRTER

289-304 _289-304 1/27/14 4:08 PM Page 294 HISTORY Medieval illuminated chronicles, breviaries, But at the same time, pestilence, famine, endless codices, psalters and manuals include a wealth dissensions, and bloody wars made it a dark time in of texts and images in which dogs play an impor- medieval Europe. tant role. Here is the story. In the early Middle Ages, the nobility had com- plete authority over a mass of commoners. Farmers BONDSMEN, FARMERS, had to turn over most of their output to the landown- NOBILITY AND CLERGY ers, and respect their privileges, including hunting, fishing and judicial rights. Historians count the Middle Ages as between the The contrasts were huge. While commoners lived 5th and 15th centuries. The development of agricul- in miserable circumstances, the nobility and clergy ture, rise of towns, extension of markets and trade; lived in luxury. the position of bondsmen, farmers, nobility and Images of medieval dogs show an almost exclu- clergy; and the evolution of secular art from the her- sive relationship with the highly placed. Bondsmen, itage of religious art were important events during serfs and farmers had no belongings; they were these centuries. themselves someone’s possession. DOGS IN MEDIEVAL ART text and illustrations by RIA HÖRTER SOURCES The sources I referred to for this article are di- verse: handwritten manuscripts, printed books, books of hours, breviaries, bestiaries and how-to books for the medieval upper class. The Rochester Bestiary is an outstanding example of a manuscript with many pictures of dogs. It is almost unbelievable that, at the beginning of the 13th century, artists could create such a beautiful and accurate work.