A History of Syriac Christianity, Part II

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

780S Series Spray Valves VALVEMATE™ 7040 Controller Operating Manual

780S Series Spray Valves VALVEMATE™ 7040 Controller Operating Manual ® A NORDSON COMPANY US: 888-333-0311 UK: 0800 585733 Mexico: 001-800-556-3484 If you require any assistance or have spe- cific questions, please contact us. US: 888-333-0311 Telephone: 401-434-1680 Fax: 401-431-0237 E-mail: [email protected] Mexico: 001-800-556-3484 UK: 0800 585733 EFD Inc. 977 Waterman Avenue, East Providence, RI 02914-1342 USA Sales and service of EFD Dispense Valve Systems is available through EFD authorized distributors in over 30 countries. Please contact EFD U.S.A. for specific names and addresses. Contents Introduction ..................................................................2 Specifications ..............................................................3 How The Valve and Controller Operate ......................4 Controller Operating Features ....................................5 Typical Setup ..............................................................6 Setup ........................................................................7-8 Adjusting the Spray......................................................9 Programming Nozzle Air Delay ..................................10 Spray Patterns ..........................................................11 Troubleshooting Guide ........................................12-13 Valve Maintenance................................................14-16 780S Exploded View..................................................17 Input / Output Connections..................................18-19 Connecting -

The Syrian Orthodox Church and Its Ancient Aramaic Heritage, I-Iii (Rome, 2001)

Hugoye: Journal of Syriac Studies 5:1, 63-112 © 2002 by Beth Mardutho: The Syriac Institute SOME BASIC ANNOTATION TO THE HIDDEN PEARL: THE SYRIAN ORTHODOX CHURCH AND ITS ANCIENT ARAMAIC HERITAGE, I-III (ROME, 2001) SEBASTIAN P. BROCK UNIVERSITY OF OXFORD [1] The three volumes, entitled The Hidden Pearl. The Syrian Orthodox Church and its Ancient Aramaic Heritage, published by TransWorld Film Italia in 2001, were commisioned to accompany three documentaries. The connecting thread throughout the three millennia that are covered is the Aramaic language with its various dialects, though the emphasis is always on the users of the language, rather than the language itself. Since the documentaries were commissioned by the Syrian Orthodox community, part of the third volume focuses on developments specific to them, but elsewhere the aim has been to be inclusive, not only of the other Syriac Churches, but also of other communities using Aramaic, both in the past and, to some extent at least, in the present. [2] The volumes were written with a non-specialist audience in mind and so there are no footnotes; since, however, some of the inscriptions and manuscripts etc. which are referred to may not always be readily identifiable to scholars, the opportunity has been taken to benefit from the hospitality of Hugoye in order to provide some basic annotation, in addition to the section “For Further Reading” at the end of each volume. Needless to say, in providing this annotation no attempt has been made to provide a proper 63 64 Sebastian P. Brock bibliography to all the different topics covered; rather, the aim is simply to provide specific references for some of the more obscure items. -

From Beit Abhe to Angamali: Connections, Functions and Roles of the Church of the East’S Monasteries in Ninth Century Christian-Muslim Relations

Middlesex University Research Repository An open access repository of Middlesex University research http://eprints.mdx.ac.uk Cochrane, Steve (2014) From Beit Abhe to Angamali: connections, functions and roles of the Church of the East’s monasteries in ninth century Christian-Muslim relations. PhD thesis, Middlesex University / Oxford Centre for Mission Studies. [Thesis] Final accepted version (with author’s formatting) This version is available at: https://eprints.mdx.ac.uk/13988/ Copyright: Middlesex University Research Repository makes the University’s research available electronically. Copyright and moral rights to this work are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners unless otherwise stated. The work is supplied on the understanding that any use for commercial gain is strictly forbidden. A copy may be downloaded for personal, non-commercial, research or study without prior permission and without charge. Works, including theses and research projects, may not be reproduced in any format or medium, or extensive quotations taken from them, or their content changed in any way, without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder(s). They may not be sold or exploited commercially in any format or medium without the prior written permission of the copyright holder(s). Full bibliographic details must be given when referring to, or quoting from full items including the author’s name, the title of the work, publication details where relevant (place, publisher, date), pag- ination, and for theses or dissertations the awarding institution, the degree type awarded, and the date of the award. If you believe that any material held in the repository infringes copyright law, please contact the Repository Team at Middlesex University via the following email address: [email protected] The item will be removed from the repository while any claim is being investigated. -

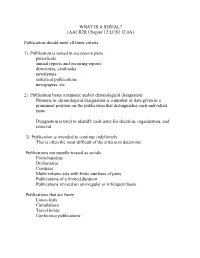

WHAT IS a SERIAL? (AACR2R Chapter 12/LCRI 12.0A)

WHAT IS A SERIAL? (AACR2R Chapter 12/LCRI 12.0A) Publication should meet all three criteria 1) Publication is issued in successive parts periodicals annual reports and recurring reports directories, yearbooks newsletters statistical publications newspapers, etc. 2) Publication bears a numeric and/or chronological designation Numeric or chronological designation is a number or date given in a prominent position on the publication that distinguishes each individual issue Designation is used to identify each issue for check-in, organization, and retrieval 3) Publication is intended to continue indefinitely This is often the most difficult of the criteria to determine Publications not usually treated as serials Encyclopedias Dictionaries Censuses Multi-volume sets with finite numbers of parts Publications of a limited duration Publications revised on an irregular or infrequent basis Publications that are fuzzy Loose-leafs Cumulations Travel books Conference publications KEY POINTS OF SERIALS CATALOGING Base description on first or earliest issue. Every serial record should have a 362 or a 500 Description based on note. New record is created each time the title proper or corporate body (if main entry) changes. (See Serial title changes that require a new record) Cataloging record must represent the entire serial. Bib record must be general enough to apply to the entire serial, but specific enough to cover all access points. Notes are used to show changes in place of publication, publisher, issuing body, frequency, etc. Serial records should never have ISBN numbers for separate issues. Every serial should have a unique title. This is often accomplished with uniform titles. (See Uniform titles) Most serials do not have personal authors. -

Byzantium and Bulgaria, 775-831

Byzantium and Bulgaria, 775–831 East Central and Eastern Europe in the Middle Ages, 450–1450 General Editor Florin Curta VOLUME 16 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.nl/ecee Byzantium and Bulgaria, 775–831 By Panos Sophoulis LEIDEN • BOSTON 2012 Cover illustration: Scylitzes Matritensis fol. 11r. With kind permission of the Bulgarian Historical Heritage Foundation, Plovdiv, Bulgaria. Brill has made all reasonable efforts to trace all rights holders to any copyrighted material used in this work. In cases where these efforts have not been successful the publisher welcomes communications from copyright holders, so that the appropriate acknowledgements can be made in future editions, and to settle other permission matters. This book is printed on acid-free paper. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Sophoulis, Pananos, 1974– Byzantium and Bulgaria, 775–831 / by Panos Sophoulis. p. cm. — (East Central and Eastern Europe in the Middle Ages, 450–1450, ISSN 1872-8103 ; v. 16.) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-90-04-20695-3 (hardback : alk. paper) 1. Byzantine Empire—Relations—Bulgaria. 2. Bulgaria—Relations—Byzantine Empire. 3. Byzantine Empire—Foreign relations—527–1081. 4. Bulgaria—History—To 1393. I. Title. DF547.B9S67 2011 327.495049909’021—dc23 2011029157 ISSN 1872-8103 ISBN 978 90 04 20695 3 Copyright 2012 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands. Koninklijke Brill NV incorporates the imprints Brill, Global Oriental, Hotei Publishing, IDC Publishers, Martinus Nijhoff Publishers and VSP. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, translated, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission from the publisher. -

The Denarius – in the Middle Ages the Basis for Everyday Money As Well

The Denarius – in the Middle Ages the Basis for Everyday Money as well In France the coin was known as "denier," in Italy as "denaro," in German speaking regions as "Pfennig," in England as "penny," – but in his essence, it always was the denarius, the traditional silver coin of ancient Rome. In his coinage reform of the 780s AD, Charlemagne had revalued and reintroduced the distinguished denarius as standard coin of the Carolingian Empire. Indeed for the following 700 years, the denarius remained the major European trade coin. Then, in the 13th century, the Carolingian denarius developed into the "grossus denarius," a thick silver coin of six denarii that was later called "gros," "grosso," "groschen" or "groat." The denarius has lasted until this day – for instance in the dime, the North American 10 cent-coin. But see for yourself. 1 von 15 www.sunflower.ch Frankish Empire, Charlemagne (768-814), Denarius (Pfennig), after 794, Milan Denomination: Denarius (Pfennig) Mint Authority: Emperor Charlemagne Mint: Milan Year of Issue: 793 Weight (g): 1.72 Diameter (mm): 20.0 Material: Silver Owner: Sunflower Foundation The pfennig was the successor to the Roman denarius. The German word "pfennig" and the English term "penny" correspond to the Latin term "denarius" – the d on the old English copper pennies derived precisely from this connection. The French coin name "denier" stemmed from the Latin term as well. This pfennig is a coin of Charlemagne, who in 793/794 conducted a comprehensive reform of the Carolingian coinage. Charlemagne's "novi denarii," as they were called in the Synod of Frankfurt in 794, bore the royal monogram that was also used to authenticate official documents. -

Directory of Commercial Testing and College Research Laboratories

DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE BUREAU OF STANDARDS GEORGE K. BURGESS, Director DIRECTORY OF COMMERCIAL TESTING AND COLLEGE RESEARCH LABORATORIES MISCELLANEOUS PUBLICATION No. 90 BUREAU OF STANDARDS PAMPHLETS ON TESTING There are listed below a few of the official publications of the Bureau of Standards relating to certain phases of testing, including Scientific Papers (S), Technologic Papers (T), Circulars (C), and Miscellaneous Publications (M). Copies of the pamphlets can be obtained, at the prices stated, from the Superintendent of Documents, Government Printing Office, Washington, D. C. In ordering pamphlets from the Superintendent of Documents the bureau publication symbol and number must be stated, and the order must be accompanied by cash. Automobile-tire fabric testing, standardization of, Hose, garden, selection and care of C327. (In T68. Price, 10 cents. press.) Hydrogen sulphide in gas, lead acetate test for, T41. Bags, paper, for cement and lime, a study of test Price, 25 cents. methods for, T187. Price, 5 cents. Hydrometers, testing of, CI 6. Price, 5 cents. Barometers, the testing of, C46. Price, 10 cents. Inks, their composition, Beams, reinforced concrete, shear tests of, T314. manufacture, and methods of testing, C95. Price, 10 Price, 50 cents. cents. Inks, printing, the composition, properties, and test- Bricks, transverse test of, T251. Price, 10 cents. ing of, C53. Price, 10 cents. Bridge columns, large, tests of, T101. Price, 30 cents. Lamp life-testing equipment and methods, recent Cast steel, centrifugally, tests of, T192. Price, 10 developments in, T325. Price, 15 cents. cents. Lamps, incandescent, life testing of, S265. Price, Clay refractories, the testing of, with special refer- 10 cents. -

A Watchman on the Walls: Ezekiel and Reaction to Invasion in Anglo-Saxon England Max K

University of Arkansas, Fayetteville ScholarWorks@UARK Theses and Dissertations 5-2016 A Watchman on the Walls: Ezekiel and Reaction to Invasion in Anglo-Saxon England Max K. Brinson University of Arkansas, Fayetteville Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd Part of the European History Commons, History of Christianity Commons, and the Literature in English, British Isles Commons Recommended Citation Brinson, Max K., "A Watchman on the Walls: Ezekiel and Reaction to Invasion in Anglo-Saxon England" (2016). Theses and Dissertations. 1595. http://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd/1595 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UARK. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UARK. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. A Watchman on the Walls: Ezekiel and Reaction to Invasion in Anglo-Saxon England A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History Max Brinson University of Central Arkansas Bachelor of Arts in History, 2011 University of Central Arkansas Bachelor of Arts in Creative Writing, 2011 May 2016 University of Arkansas This thesis is approved for recommendation to the Graduate Council. Dr. Joshua Smith Thesis Director Dr. Lynda Coon Dr. Charles Muntz Committee Member Committee Member Abstract During the Viking Age, the Christian Anglo-Saxons in England found warnings and solace in the biblical text of Ezekiel. In this text, the God of Israel delivers a dual warning: first, the sins of the people call upon themselves divine wrath; second, it is incumbent upon God’s messenger to warn the people of their extreme danger, or else find their blood on his hands. -

When You Specify Boringly Reliable Fluid Dispense Valve Systems, You Say "Good-Bye" to Costly Downtime

® A NORDSON COMPANY When you specify boringly reliable fluid dispense valve systems, you say "Good-bye" to costly downtime. ® Quiet dependable The best fluid dispense valve system is the one you forget about. EFD precision fluid dispense valves eliminate or significantly reduce production downtime costs. When maintenance is required, simplified procedures mean minimal interruption. EFD dispense valves—maximum reliability with the lowest "fuss" factor. Engineered for the most demanding mechanical and envi- ronmental applications, EFD valve systems provide very reliable dispensing solutions for benchtop applications, machine builders, and very cost-effective, drop-in retrofit alternatives for machine operators. Index Valve features and selector — pages 4 to 5 Dispense valves — pages 6 to 27 diaphragm, piston, high flow, needle, high pressure, spray, internal spray, coating, auger Applications — pages 28 to 29 Valve controllers — pages 30 to 35 VALVEMATE™ 7000 and controllers for spray, internal spray and auger systems 735HPA spool valve applies even stripes of structural adhesive to brake shoe linings. Fluid reservoirs — page 36 2.5 oz. cartridges, one liter and 5.0 liter tanks Fuel injection manifold bores on Ford engines receive a fine coating of oil without overspray Dispensing tips — page 37 by using 780S-SS spray valves. photo courtesy of Ford Motor Company Recommendations — page 39 Fine flow control of the 752V-SS diaphragm valve evenly coats compact disc with UV-cure lacquer. photo courtesy of Weld-Equip Europe 2 dispense valve systems Proof of performance Before you commit to EFD dispense valve systems, you want to thoroughly prove the value of this change. EFD will provide at no cost a complete evaluation system for your testing—valve, controller and tank reservoir. -

Lost History of Christianity Were Conjoined and Commingled

www.malankaralibrary.com www.malankaralibrary.com The Lost History of Chris tianity The Thousand-Year Golden Age of the Church in the Middle East, Africa, and Asia—and How It Died Philip Jenkins www.malankaralibrary.com www.malankaralibrary.com Contents List of Illustrations iv A Note on Names and -isms v 1. The End of Global Chris tian ity 1 2. Churches of the East 45 3. Another World 71 4. The Great Tribulation 97 5. The Last Chris tians 139 6. Ghosts of a Faith 173 7. How Faiths Die 207 8. The Mystery of Survival 227 9. Endings and Beginnings 247 Notes 263 Acknowledgments 299 Index 301 3 About the Author Credits Cover Copyright About the Publisher www.malankaralibrary.com Illustrations Maps 1.1. Nestorian Metropolitans 12 1.2. Chris tian Expansion 21 1.3. The Three-Fold World 23 2.1. The Sassanian Persian Empire 51 2.2. The Heart of the Chris tian Middle East 59 Tables 4.1. Chronology of Early Islam 101 5.1. Muslims in Contemporary Southeastern Europe 144 5.2. Chris tians in the Middle East Around 1910 153 5.3. The Chris tian World Around 1900 155 www.malankaralibrary.com A Note on Names and -isms Throughout this book, I refer to the Eastern Christian churches that are commonly known as Jacobite and Nestorian. Both names raise problems, and some historical explanation is useful at the outset. At the risk of ignoring subtle theological distinctions, though, a reader would not go far wrong by understanding both terms as meaning simply “ancient Chris tian denominations mainly active outside Europe.” Chris tian ity originated in the Near East, and during the fi rst few centuries it had its greatest centers, its most prestigious churches and monasteries, in Syria, Palestine, and Mesopotamia. -

Yazdandukht and Mar Qardagh from the Persian Martyr Acts in Syriac to Sureth Poetry on Youtube, Via a Historical Novel in Arabic

Kervan – International Journal of Afro-Asiatic Studies n. 24/2 (2020) Yazdandukht and Mar Qardagh From the Persian martyr acts in Syriac to Sureth poetry on YouTube, via a historical novel in Arabic Alessandro Mengozzi Videos posted on YouTube show how stories of East-Syriac saints have found their way to a popular web platform, where they are re-told combining traditional genres with a culturally hybrid visual representation. The sketchy female characters Yazdandukht and Yazdui/Christine and the fully developed epos of Mar Qardagh, who belong to the narrative cycle of the Persian martyrs of Erbil and Kirkuk, inspired an Arabic illustrated historical novel, published in 1934 by the Chaldean bishop Sulaymān Ṣā’igh. A few years after the publication of the novel, a new cult of Mar Qardagh was established in Alqosh, in northern Iraq, including the building of a shrine, the painting of an icon, public and private rites, and the composition of hymns. In 1969 the Chaldean priest Yoḥannan Cholagh adapted Ṣā’igh’s Arabic novel to a traditional long stanzaic poem in the Aramaic dialect of Alqosh. The poem On Yazdandukht, as chanted by the poet himself, became the soundtrack of a video published on YouTube in 2014. Keywords: Hagiography, Persian martyr acts, Arabic historical novel, Neo-Aramaic, Classical Syriac Non esiste una terra dove non ci son santi né eroi. E. Bennato, L’isola che non c’è Social networks and mass media technologies offer various easily accessible and usable multimedia platforms to produce and reproduce cultural products, usually playing on the interaction of texts, music and images, and multiply the performance arenas in and for which these products are conceived. -

Propositiones Ad Acuendos Iuvenes

‘ECCE FABULA!’ PROBLEM-SOLVING BY NUMBERS IN THE CAROLINGIAN WORLD: THE CASE OF THE PROPOSITIONES AD ACUENDOS IUVENES BY RUTGER KRAMER Austrian Academy of Sciences 'Ich habe bemerkt', sagte Herr K., 'daß wir viele abschrecken von unserer Lehre dadurch, daß wir auf alles eine Antwort wissen. Könnten wir nicht im Interesse der Propaganda eine Liste der Fragen aufstellen, die uns ganz ungelöst 1 erscheinen?' Sometime in the mid-780s, Charlemagne, King of the Franks, had a letter composed in his name, and sent it to all of the abbots and bishops in his realm. His goals were as ambitious as they were reflective of a basic need to reinvigorate the pursuit of knowledge among his prelates. To start this endeavour, the letter states, it was vital to make sure that education in the realm was up to par: For although correct conduct may be better than knowledge, 1 Bertolt Brecht, Geschichten vom Herrn Keuner (Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp, 1971), ll. 239-43 ['"I have noticed", said Mr. K., "that we put many people off our teaching because we have an answer to everything. Could we not, in the interests of propaganda, draw up a list of questions that appear to us completely unsolved?"', Stories of Mr. Keuner, trans. by Martin Chalmers (San Francisco: City Lights Books, 2001), p. 18]. 16 Rutger Kramer nevertheless knowledge precedes conduct. Therefore, everyone ought to study what he desires to accomplish, so that so much the more fully the mind may know what ought to be done, as the tongue hastens in the praises of omnipotent God without the hindrances of errors.