Appropriations of the Master's Legacy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Towards Chinese Calligraphy Zhuzhong Qian

Macalester International Volume 18 Chinese Worlds: Multiple Temporalities Article 12 and Transformations Spring 2007 Towards Chinese Calligraphy Zhuzhong Qian Desheng Fang Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/macintl Recommended Citation Qian, Zhuzhong and Fang, Desheng (2007) "Towards Chinese Calligraphy," Macalester International: Vol. 18, Article 12. Available at: http://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/macintl/vol18/iss1/12 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Institute for Global Citizenship at DigitalCommons@Macalester College. It has been accepted for inclusion in Macalester International by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Macalester College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Towards Chinese Calligraphy Qian Zhuzhong and Fang Desheng I. History of Chinese Calligraphy: A Brief Overview Chinese calligraphy, like script itself, began with hieroglyphs and, over time, has developed various styles and schools, constituting an important part of the national cultural heritage. Chinese scripts are generally divided into five categories: Seal script, Clerical (or Official) script, Regular script, Running script, and Cursive script. What follows is a brief introduction of the evolution of Chinese calligraphy. A. From Prehistory to Xia Dynasty (ca. 16 century B.C.) The art of calligraphy began with the creation of Chinese characters. Without modern technology in ancient times, “Sound couldn’t travel to another place and couldn’t remain, so writings came into being to act as the track of meaning and sound.”1 However, instead of characters, the first calligraphy works were picture-like symbols. These symbols first appeared on ceramic vessels and only showed ambiguous con- cepts without clear meanings. -

780S Series Spray Valves VALVEMATE™ 7040 Controller Operating Manual

780S Series Spray Valves VALVEMATE™ 7040 Controller Operating Manual ® A NORDSON COMPANY US: 888-333-0311 UK: 0800 585733 Mexico: 001-800-556-3484 If you require any assistance or have spe- cific questions, please contact us. US: 888-333-0311 Telephone: 401-434-1680 Fax: 401-431-0237 E-mail: [email protected] Mexico: 001-800-556-3484 UK: 0800 585733 EFD Inc. 977 Waterman Avenue, East Providence, RI 02914-1342 USA Sales and service of EFD Dispense Valve Systems is available through EFD authorized distributors in over 30 countries. Please contact EFD U.S.A. for specific names and addresses. Contents Introduction ..................................................................2 Specifications ..............................................................3 How The Valve and Controller Operate ......................4 Controller Operating Features ....................................5 Typical Setup ..............................................................6 Setup ........................................................................7-8 Adjusting the Spray......................................................9 Programming Nozzle Air Delay ..................................10 Spray Patterns ..........................................................11 Troubleshooting Guide ........................................12-13 Valve Maintenance................................................14-16 780S Exploded View..................................................17 Input / Output Connections..................................18-19 Connecting -

Armed Communities and Military Resources in Late Medieval China (880-936) Maddalena Barenghi Università Ca’ Foscari Venezia, Italia

e-ISSN 2385-3042 Annali di Ca’ Foscari. Serie orientale Vol. 57 – Giugno 2021 North of Dai: Armed Communities and Military Resources in Late Medieval China (880-936) Maddalena Barenghi Università Ca’ Foscari Venezia, Italia Abstract This article discusses various aspects of the formation of the Shatuo as a complex constitutional process from armed mercenary community to state found- ers in the waning years of Tang rule and the early tenth century period (880-936). The work focuses on the territorial, economic, and military aspects of the process, such as the strategies to secure control over resources and the constitution of elite privileges through symbolic kinship ties. Even as the region north of the Yanmen Pass (Daibei) remained an important pool of recruits for the Shatuo well into the tenth century, the Shatuo leaders struggled to secure control of their core manpower, progressively moving away from their military base of support, or losing it to their competitors. Keywords Shatuo. Tang-Song transition. Frontier clients. Daibei. Khitan-led Liao. Summary 1 Introduction. – 2 Geography of the Borderland and Migrant Forces. – 3 Feeding the Troops: Authority and the Control of Military Resources. – 4 Li Keyong’s Client Army: Daibei in the Aftermath of the Datong Military Insurrection (883-936). – 5 Concluding Remarks. Peer review Submitted 2021-01-14 Edizioni Accepted 2021-04-22 Ca’Foscari Published 2021-06-30 Open access © 2021 | cb Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Public License Citation Barenghi, M. (2021). “North of Dai: Armed Communities and Mili- tary Resources in Late Medieval China (880-936)”. Annali di Ca’ Foscari. -

Christian Women and the Making of a Modern Chinese Family: an Exploration of Nü Duo 女鐸, 1912–1951

Christian Women and the Making of a Modern Chinese Family: an Exploration of Nü duo 女鐸, 1912–1951 Zhou Yun A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The Australian National University February 2019 © Copyright by Zhou Yun 2019 All Rights Reserved Except where otherwise acknowledged, this thesis is my own original work. Acknowledgements I would like to express my deep gratitude to my supervisor Dr. Benjamin Penny for his valuable suggestions and constant patience throughout my five years at The Australian National University (ANU). His invitation to study for a Doctorate at Australian Centre on China in the World (CIW) not only made this project possible but also kindled my academic pursuit of the history of Christianity. Coming from a research background of contemporary Christian movements among diaspora Chinese, I realise that an appreciation of the present cannot be fully achieved without a thorough study of the past. I was very grateful to be given the opportunity to research the Republican era and in particular the development of Christianity among Chinese women. I wish to thank my two co-advisers—Dr. Wei Shuge and Dr. Zhu Yujie—for their time and guidance. Shuge’s advice has been especially helpful in the development of my thesis. Her honest critiques and insightful suggestions demonstrated how to conduct conscientious scholarship. I would also like to extend my thanks to friends and colleagues who helped me with my research in various ways. Special thanks to Dr. Caroline Stevenson for her great proof reading skills and Dr. Paul Farrelly for his time in checking the revised parts of my thesis. -

Historiography and Narratives of the Later Tang (923-936) and Later Jin (936-947) Dynasties in Tenth- to Eleventh- Century Sources

Historiography and Narratives of the Later Tang (923-936) and Later Jin (936-947) Dynasties in Tenth- to Eleventh- century Sources Inauguraldissertation zur Erlangung des Doktorgrades der Philosophie an der Ludwig‐Maximilians‐Universität München vorgelegt von Maddalena Barenghi Aus Mailand 2014 Erstgutachter: Prof. Dr. Hans van Ess Zweitgutachter: Prof. Tiziana Lippiello Datum der mündlichen Prüfung: 31.03.2014 ABSTRACT Historiography and Narratives of the Later Tang (923-36) and Later Jin (936-47) Dynasties in Tenth- to Eleventh-century Sources Maddalena Barenghi This thesis deals with historical narratives of two of the Northern regimes of the tenth-century Five Dynasties period. By focusing on the history writing project commissioned by the Later Tang (923-936) court, it first aims at questioning how early-tenth-century contemporaries narrated some of the major events as they unfolded after the fall of the Tang (618-907). Second, it shows how both late- tenth-century historiographical agencies and eleventh-century historians perceived and enhanced these historical narratives. Through an analysis of selected cases the thesis attempts to show how, using the same source material, later historians enhanced early-tenth-century narratives in order to tell different stories. The five cases examined offer fertile ground for inquiry into how the different sources dealt with narratives on the rise and fall of the Shatuo Later Tang and Later Jin (936- 947). It will be argued that divergent narrative details are employed both to depict in different ways the characters involved and to establish hierarchies among the historical agents. Table of Contents List of Rulers ............................................................................................................ ii Aknowledgements .................................................................................................. -

Chinese Ceramics in the Late Tang Dynasty

44 Chinese Ceramics in the Late Tang Dynasty Regina Krahl The first half of the Tang dynasty (618–907) was a most prosperous period for the Chinese empire. The capital Chang’an (modern Xi’an) in Shaanxi province was a magnet for international traders, who brought goods from all over Asia; the court and the country’s aristocracy were enjoying a life of luxury. The streets of Chang’an were crowded with foreigners from distant places—Central Asian, Near Eastern, and African—and with camel caravans laden with exotic produce. Courtiers played polo on thoroughbred horses, went on hunts with falconers and elegant hounds, and congregated over wine while being entertained by foreign orchestras and dancers, both male and female. Court ladies in robes of silk brocade, with jewelry and fancy shoes, spent their time playing board games on dainty tables and talking to pet parrots, their faces made up and their hair dressed into elaborate coiffures. This is the picture of Tang court life portrayed in colorful tomb pottery, created at great expense for lavish burials. By the seventh century the manufacture of sophisticated pottery replicas of men, beasts, and utensils had become a huge industry and the most important use of ceramic material in China (apart from tilework). Such earthenware pottery, relatively easy and cheap to produce since the necessary raw materials were widely available and firing temperatures relatively low (around 1,000 degrees C), was unfit for everyday use; its cold- painted pigments were unstable and its lead-bearing glazes poisonous. Yet it was perfect for creating a dazzling display at funeral ceremonies (fig. -

Revisiting the Scene of the Party: a Study of the Lanting Collection

Revisiting the Scene of the Party: A Study of the Lanting Collection WENDY SWARTZ RUTGERS UNIVERSITY The Lanting (sometimes rendered as "Orchid Pavilion") gathering in 353 is one of the most famous literati parties in Chinese history. ' This gathering inspired the celebrated preface written by the great calligrapher Wang Xizhi ï^è. (303-361), another preface by the poet Sun Chuo i^s^ (314-371), and forty-one poems composed by some of the most intellectu- ally active men of the day.^ The poems are not often studied since they have long been over- shadowed by Wang's preface as a work of calligraphic art and have been treated as examples oí xuanyan ("discourse on the mysterious [Dao]") poetry,^ whose fate in literary history suffered after influential Six Dynasties writers decried its damage to the classical tradition. '^ Historian Tan Daoluan tliË;^ (fl. 459) traced the trend to its full-blown development in Sun Chuo and Xu Xun l^gt] (fl. ca. 358), who were said to have continued the work of inserting Daoist terms into poetry that was started by Guo Pu MM (276-324); they moreover "added the [Buddhist] language of the three worlds [past, present, and future], and the normative style of the Shi W and Sao M came to an end."^ Critic Zhong Rong M^ (ca. 469-518) then faulted their works for lacking appeal. His critique was nothing short of scathing: he argued Earlier versions of this article were presented at the annual meeting of the Association for Asian Studies in Phil- adelphia in March 2012 and at a lecture delivered at Tel Aviv University in May, 2011, and I am grateful to have had the chance to present my work at both venues. -

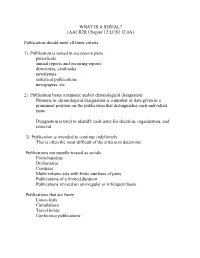

WHAT IS a SERIAL? (AACR2R Chapter 12/LCRI 12.0A)

WHAT IS A SERIAL? (AACR2R Chapter 12/LCRI 12.0A) Publication should meet all three criteria 1) Publication is issued in successive parts periodicals annual reports and recurring reports directories, yearbooks newsletters statistical publications newspapers, etc. 2) Publication bears a numeric and/or chronological designation Numeric or chronological designation is a number or date given in a prominent position on the publication that distinguishes each individual issue Designation is used to identify each issue for check-in, organization, and retrieval 3) Publication is intended to continue indefinitely This is often the most difficult of the criteria to determine Publications not usually treated as serials Encyclopedias Dictionaries Censuses Multi-volume sets with finite numbers of parts Publications of a limited duration Publications revised on an irregular or infrequent basis Publications that are fuzzy Loose-leafs Cumulations Travel books Conference publications KEY POINTS OF SERIALS CATALOGING Base description on first or earliest issue. Every serial record should have a 362 or a 500 Description based on note. New record is created each time the title proper or corporate body (if main entry) changes. (See Serial title changes that require a new record) Cataloging record must represent the entire serial. Bib record must be general enough to apply to the entire serial, but specific enough to cover all access points. Notes are used to show changes in place of publication, publisher, issuing body, frequency, etc. Serial records should never have ISBN numbers for separate issues. Every serial should have a unique title. This is often accomplished with uniform titles. (See Uniform titles) Most serials do not have personal authors. -

A Failed Peripheral Hegemonic State with a Limited Mandate of Heaven: Politico-Historical Reflections of a ∗ Survivor of the Southern Tang

DOI: 10.6503/THJCS.201806_48(2).0002 A Failed Peripheral Hegemonic State with a Limited Mandate of Heaven: Politico-Historical Reflections of a ∗ Survivor of the Southern Tang Li Cho-ying∗∗ Institute of History National Tsing Hua University ABSTRACT This article focuses on the concepts the Diaoji litan 釣磯立談 author, a survivor of the Southern Tang, developed to understand the history of the kingdom. It discusses his historical discourse and shows that one of its purposes was to secure a legitimate place in history for the Southern Tang. The author developed a crucial concept, the “peripheral hegemonic state” 偏霸, to comprehend its history. This concept contains an idea of a limited mandate of heaven, a geopolitical analysis of the Southern Tang situation, and a plan for the kingdom to compete with its rivals for the supreme political authority over all under heaven. With this concept, the Diaoji author implicitly disputes official historiography’s demeaning characterization of the Southern Tang as “pseudo” 偽, and founded upon “usurpation” 僭 and “thievery” 竊. He condemns the second ruler, Li Jing 李璟 (r. 943-961) and several ministers for abandoning the first ruler Li Bian’s 李 (r. 937-943) plan, thereby leading the kingdom astray. The work also stresses the need to recruit authentic Confucians to administer the government. As such, this article argues that the Diaoji should be understood as a politico-historical book of the late tenth century. Key words: Southern Tang, survivor, Diaoji litan 釣磯立談, peripheral hegemonic state, mandate of heaven ∗ The author thanks Professors Charles Hartman, Liang Ken-yao 梁庚堯, and the two anonymous reviewers for their thoughtful comments. -

Download File

On A Snowy Night: Yishan Yining (1247-1317) and the Development of Zen Calligraphy in Medieval Japan Xiaohan Du Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy under the Executive Committee of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2021 © 2021 Xiaohan Du All Rights Reserved Abstract On A Snowy Night: Yishan Yining (1247-1317) and the Development of Zen Calligraphy in Medieval Japan Xiaohan Du This dissertation is the first monographic study of the monk-calligrapher Yishan Yining (1247- 1317), who was sent to Japan in 1299 as an imperial envoy by Emperor Chengzong (Temur, 1265-1307. r. 1294-1307), and achieved unprecedented success there. Through careful visual analysis of his extant oeuvre, this study situates Yishan’s calligraphy synchronically in the context of Chinese and Japanese calligraphy at the turn of the 14th century and diachronically in the history of the relationship between calligraphy and Buddhism. This study also examines Yishan’s prolific inscriptional practice, in particular the relationship between text and image, and its connection to the rise of ink monochrome landscape painting genre in 14th century Japan. This study fills a gap in the history of Chinese calligraphy, from which monk- calligraphers and their practices have received little attention. It also contributes to existing Japanese scholarship on bokuseki by relating Zen calligraphy to religious and political currents in Kamakura Japan. Furthermore, this study questions the validity of the “China influences Japan” model in the history of calligraphy and proposes a more fluid and nuanced model of synthesis between the wa and the kan (Japanese and Chinese) in examining cultural practices in East Asian culture. -

The Forbidden Classic of the Jade Hall: a Study of an Eleventh-Century Compendium on Calligraphic Technique

forbidden classic of the jade hall pietro de laurentis The Forbidden Classic of the Jade Hall: A Study of an Eleventh-century Compendium on Calligraphic Technique pecific texts regarding the scripts of the Chinese writing system and S the art of calligraphy began appearing in China at the end of the first century ce.1 Since the Postface to the Discussion of Single Characters and Explanation of Compound Characters (Shuowen jiezi xu 說文解字序) by Xu Shen 許慎 (ca. 55–ca. 149),2 and the Description 3 of the Cursive Script I would like to express my deepest gratitude to Ms. Chin Ching Soo for having provided sharp comments to the text, for having polished my English, and for having made the pres- ent paper much more readable. I would also like to thank Howard L. Goodman for his help in rendering several tricky passages from Classical Chinese into English. 1 On the origin of calligraphic texts, see Zhang Tiangong 張天弓, “Gudai shulun de zhao- shi: cong Ban Chao dao Cui Yuan” 古 代 書 論 的 肇 始:從 班 超 到 崔 瑗 , Shufa yanjiu 書法研究 (2003.3), pp. 64–76. 2 Completed in 100 ce; postface included in the Anthology of the Calligraphy Garden (Shu yuan jinghua 書苑菁華), 20 juan, edited by Chen Si 陳思 (fl. 13th c.), preface by Wei Liaoweng 魏了翁 (1178–1237), reproduction of the Southern Song dynasty (1127–1279) edition published in the series Zhonghua zaizao shanben 中華再造善本 (Beijing: Beijing tushuguan chubanshe, 2003), j. 16. English translation by Kenneth Thern, Postface of the Shuo-wen Chieh-tzu (Madison: University of Wisconsin, 1966), pp. -

Byzantium and Bulgaria, 775-831

Byzantium and Bulgaria, 775–831 East Central and Eastern Europe in the Middle Ages, 450–1450 General Editor Florin Curta VOLUME 16 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.nl/ecee Byzantium and Bulgaria, 775–831 By Panos Sophoulis LEIDEN • BOSTON 2012 Cover illustration: Scylitzes Matritensis fol. 11r. With kind permission of the Bulgarian Historical Heritage Foundation, Plovdiv, Bulgaria. Brill has made all reasonable efforts to trace all rights holders to any copyrighted material used in this work. In cases where these efforts have not been successful the publisher welcomes communications from copyright holders, so that the appropriate acknowledgements can be made in future editions, and to settle other permission matters. This book is printed on acid-free paper. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Sophoulis, Pananos, 1974– Byzantium and Bulgaria, 775–831 / by Panos Sophoulis. p. cm. — (East Central and Eastern Europe in the Middle Ages, 450–1450, ISSN 1872-8103 ; v. 16.) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-90-04-20695-3 (hardback : alk. paper) 1. Byzantine Empire—Relations—Bulgaria. 2. Bulgaria—Relations—Byzantine Empire. 3. Byzantine Empire—Foreign relations—527–1081. 4. Bulgaria—History—To 1393. I. Title. DF547.B9S67 2011 327.495049909’021—dc23 2011029157 ISSN 1872-8103 ISBN 978 90 04 20695 3 Copyright 2012 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands. Koninklijke Brill NV incorporates the imprints Brill, Global Oriental, Hotei Publishing, IDC Publishers, Martinus Nijhoff Publishers and VSP. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, translated, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission from the publisher.