A Buried Past: the Tomb Inscription

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Historiography and Narratives of the Later Tang (923-936) and Later Jin (936-947) Dynasties in Tenth- to Eleventh- Century Sources

Historiography and Narratives of the Later Tang (923-936) and Later Jin (936-947) Dynasties in Tenth- to Eleventh- century Sources Inauguraldissertation zur Erlangung des Doktorgrades der Philosophie an der Ludwig‐Maximilians‐Universität München vorgelegt von Maddalena Barenghi Aus Mailand 2014 Erstgutachter: Prof. Dr. Hans van Ess Zweitgutachter: Prof. Tiziana Lippiello Datum der mündlichen Prüfung: 31.03.2014 ABSTRACT Historiography and Narratives of the Later Tang (923-36) and Later Jin (936-47) Dynasties in Tenth- to Eleventh-century Sources Maddalena Barenghi This thesis deals with historical narratives of two of the Northern regimes of the tenth-century Five Dynasties period. By focusing on the history writing project commissioned by the Later Tang (923-936) court, it first aims at questioning how early-tenth-century contemporaries narrated some of the major events as they unfolded after the fall of the Tang (618-907). Second, it shows how both late- tenth-century historiographical agencies and eleventh-century historians perceived and enhanced these historical narratives. Through an analysis of selected cases the thesis attempts to show how, using the same source material, later historians enhanced early-tenth-century narratives in order to tell different stories. The five cases examined offer fertile ground for inquiry into how the different sources dealt with narratives on the rise and fall of the Shatuo Later Tang and Later Jin (936- 947). It will be argued that divergent narrative details are employed both to depict in different ways the characters involved and to establish hierarchies among the historical agents. Table of Contents List of Rulers ............................................................................................................ ii Aknowledgements .................................................................................................. -

The First Emperor: Selections from the Historical Records (Oxford

oxford world’s classics THE FIRST EMPEROR Sima Qian’s Historical Records (Shiji), from which this selection is taken, is the most famous Chinese historical work, which not only established a pattern for later Chinese historical writing, but was also much admired for its literary qualities, not only in China, but also in Japan, where it became available as early as the eighth cen- tury ad. The work is vast and complex, and to appreciate its nature it is necessary to make a selection of passages concerning a particu- lar period. To this end the short-lived Qin Dynasty, which unified China in the late third century bc, has been chosen for this transla- tion as a key historical period which well illustrates Sima’s method. Sima himself lived from 145 bc to about 86 bc. He inherited the post of Grand Historiographer from his father, and was so deter- mined to complete his work that he suffered the penalty of castra- tion rather than the more honourable alternative of death when he fell foul of the Emperor. Raymond Dawson was an Emeritus Fellow of Wadham College, Oxford. He was Editor of The Legacy of China (1964) and his other publications include The Chinese Chameleon: An Analysis of European Conceptions of Chinese Civilization (1967), Imperial China (1972), The Chinese Experience (1978), Confucius (1982), A New Introduction to Classical Chinese (1984), and the Analects (Oxford World’s Classics, 1993). K. E. Brashier is Associate Professor of Religion (Chinese) and Humanities (Chinese) at Reed College. oxford world’s classics For over 100 years Oxford World’s Classics have brought readers closer to the world’s great literature. -

Issues and Potential Solutions to the Clean Heating Project in Rural Gansu

sustainability Article Issues and Potential Solutions to the Clean Heating Project in Rural Gansu Dehu Qv 1,* , Xiangjie Duan 1, Jijin Wang 2, Caiqin Hou 1, Gang Wang 1, Fengxi Zhou 1,* and Shaoyong Li 1,* 1 Department of Building Environment and Energy Application Engineering, School of Civil Engineering, Lanzhou University of Technology, Lanzhou 730050, China; [email protected] (X.D.); [email protected] (C.H.); [email protected] (G.W.) 2 School of Architecture, Harbin Institute of Technology, Key Laboratory of Cold Region Urban and Rural Human Settlement Environment Science and Technology, Ministry of Industry and Information Technology, Harbin 150090, China; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] (D.Q.); [email protected] (F.Z.); [email protected] (S.L.); Tel.: +86-931-2973715 (D.Q.) Abstract: Rural clean heating project (RCHP) in China aims to increase flexibility in the rural energy system, enhance the integration of renewable energy and distributed generation, and reduce environmental impact. While RCHP-enabling routes have been studied from a technical perspective, the economic, ecological, regulatory, and policy dimensions of RCHP are yet to be analysed in depth, especially in the underdeveloped areas in China. This paper discusses RCHP in rural Gansu using a multi-dimensional approach. We first focus on the current issues and challenges of RCHP in rural Gansu. Then the RCHP-enabling areas are briefly zoned into six typical regions based on the resource distribution in Gansu Province, and a matching framework of RCHP is recommended. Then we focus on the economics and sustainability of RCHP-enabling technologies. Based on the medium-term assessment of RCHP in the demonstration provinces, various technical schemes and routes are analysed and compared in order to determine which should be adopted in rural Gansu. -

Chinese Contemporary Art and the Value of Dissidence by Marie

Transition and Transformation: Chinese Contemporary Art and the Value of Dissidence by Marie Dorothée Leduc A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Visual Art and Globalization Department of Sociology and Art and Design University of Alberta © Marie Leduc, 2016 Abstract Transition and Transformation: Chinese Contemporary Art and the Value of Dissidence Marie Leduc Taking an interdisciplinary approach combining sociology and art history, this dissertation considers the phenomenal rise of Chinese contemporary art in the global art market since 1989. The dissertation explores how Western perceptions of difference and dissidence have contributed to the recognition and validation of Chinese contemporary art. Guided by Nathalie Heinich’s sociology of values and Pierre Bourdieu’s work on the field of cultural production, the dissertation proposes that dissidence may be understood as an artistic value, one that distinguishes artists and artwork as singular and original. Following the careers of nine Chinese artists who moved to France in and around 1989, the dissertation demonstrates how perceptions of dissidence – artistic, cultural, and political – have distinguished Chinese artists as they have transitioned into an artistic field dominated by Western liberal-democratic values and artistic taste. The transition and transformation of Chinese contemporary art and artists then highlights how the valorization of dissidence in the West is both artistic and political, and significant to the production of contemporary art. ii Preface This thesis is an original work by Marie Leduc. The research project, of which this thesis is a part, received research ethics approval from the University of Alberta Research Ethics Board, Project Name “Transition and Transformation: Contemporary Chinese Art in the Global Marketplace,” No. -

"Ancient Mirror": an Interpretation of Gujing Ji in the Context of Medieval Chinese Cultural History Ju E Chen

East Asian History NUMBER 27 . JUNE 2004 Institute of Advanced Studies Australian National University Editor Geremie R. Barme Associate Editor Helen Lo Business Manager Marion Weeks Editorial Advisors B0rge Bakken John Clark Lo uise Edwards Mark Elvin (Convenor) John Fitzgerald Colin Jeffcott Li Tana Kam Lo uie Le wis Mayo Gavan McCormack David Marr Tessa Morris-Suzuki Benjamin Penny Kenneth Wells Design and Production Design ONE Solutions, Victoria Street, Hall ACT 2618 Printed by Goanna Print, Fyshwick, ACT This is the twenty-seventh issue of Ea st Asian History, printed August 2005, in the series previously entitled Papers on Far Ea sternHist ory. This externally refereed journal is published twice a year. Contributions to The Editor, Ea st Asian Hist ory Division of Pacific and Asian History Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Phone +61 2 6125 314 0 Fax +61 26125 5525 Email [email protected] Subscription Enquiries to Marion Weeks, East Asian History, at the above address, or to [email protected]. au Annual Subscription Australia A$50 (including GST) Overseas US$45 (GST free) (for two issues) ISSN 1036-6008 iii CONTENTS 1 Friendship in Ancient China Aat Vervoom 33 The Mystery of an "Ancient Mirror": An Interpretation of Gujing ji in the Context of Medieval Chinese Cultural History Ju e Chen 51 The Missing First Page of the Preclassical Mongolian Version of the Hs iao-ching: A Tentative Reconstruction Igor de Rachewiltz 57 Historian and Courtesan: Chen Yinke !l*Ji[Nj. and the Writing of Liu Rushi Biezhuan t9P�Qjll:J,jiJf� We n-hsin Yeh 71 Demons, Gangsters, and Secret Societies in Early Modern China Robert]. -

The Eurasian Transformation of the 10Th to 13Th Centuries: the View from Song China, 906-1279

Haverford College Haverford Scholarship Faculty Publications History 2004 The Eurasian Transformation of the 10th to 13th centuries: The View from Song China, 906-1279 Paul Jakov Smith Haverford College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.haverford.edu/history_facpubs Repository Citation Smith, Paul Jakov. “The Eurasian Transformation of the 10th to 13th centuries: The View from the Song.” In Johann Arneson and Bjorn Wittrock, eds., “Eurasian transformations, tenth to thirteenth centuries: Crystallizations, divergences, renaissances,” a special edition of the journal Medieval Encounters (December 2004). This Journal Article is brought to you for free and open access by the History at Haverford Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Haverford Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Medieval 10,1-3_f12_279-308 11/4/04 2:47 PM Page 279 EURASIAN TRANSFORMATIONS OF THE TENTH TO THIRTEENTH CENTURIES: THE VIEW FROM SONG CHINA, 960-1279 PAUL JAKOV SMITH ABSTRACT This essay addresses the nature of the medieval transformation of Eurasia from the perspective of China during the Song dynasty (960-1279). Out of the many facets of the wholesale metamorphosis of Chinese society that characterized this era, I focus on the development of an increasingly bureaucratic and autocratic state, the emergence of a semi-autonomous local elite, and the impact on both trends of the rise of the great steppe empires that encircled and, under the Mongols ultimately extinguished the Song. The rapid evolution of Inner Asian state formation in the tenth through the thirteenth centuries not only swayed the development of the Chinese state, by putting questions of war and peace at the forefront of the court’s attention; it also influenced the evolution of China’s socio-political elite, by shap- ing the context within which elite families forged their sense of coorporate identity and calibrated their commitment to the court. -

A Dynamic Schedule Based on Integrated Time Performance Prediction

2009 First International Conference on Information Science and Engineering (ICISE 2009) Nanjing, China 26 – 28 December 2009 Pages 1-906 IEEE Catalog Number: CFP0976H-PRT ISBN: 978-1-4244-4909-5 1/6 TABLE OF CONTENTS TRACK 01: HIGH-PERFORMANCE AND PARALLEL COMPUTING A DYNAMIC SCHEDULE BASED ON INTEGRATED TIME PERFORMANCE PREDICTION ......................................................1 Wei Zhou, Jing He, Shaolin Liu, Xien Wang A FORMAL METHOD OF VOLUNTEER COMPUTING .........................................................................................................................5 Yu Wang, Zhijian Wang, Fanfan Zhou A GRID ENVIRONMENT BASED SATELLITE IMAGES PROCESSING.............................................................................................9 X. Zhang, S. Chen, J. Fan, X. Wei A LANGUAGE OF NEUTRAL MODELING COMMAND FOR SYNCHRONIZED COLLABORATIVE DESIGN AMONG HETEROGENEOUS CAD SYSTEMS ........................................................................................................................12 Wanfeng Dou, Xiaodong Song, Xiaoyong Zhang A LOW-ENERGY SET-ASSOCIATIVE I-CACHE DESIGN WITH LAST ACCESSED WAY BASED REPLACEMENT AND PREDICTING ACCESS POLICY.......................................................................................................................16 Zhengxing Li, Quansheng Yang A MEASUREMENT MODEL OF REUSABILITY FOR EVALUATING COMPONENT...................................................................20 Shuoben Bi, Xueshi Dong, Shengjun Xue A M-RSVP RESOURCE SCHEDULING MECHANISM IN PPVOD -

I Ideology of Power and Power of Ideology in Early China

i Ideology of Power and Power of Ideology in Early China © koninklijke brill nv, leiden, 2015 | doi 10.1163/9789004299337_001 ii Sinica Leidensia Edited by Barend J. ter Haar Maghiel van Crevel In co-operation with P.K. Bol, D.R. Knechtges, E.S. Rawski, W.L. Idema, H.T. Zurndorfer VOLUME 124 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/sinl iii Ideology of Power and Power of Ideology in Early China Edited by Yuri Pines Paul R. Goldin Martin Kern LEIDEN | BOSTON iv Cover illustration: Tripod cooking vessel with lid (ding), late 6th century bc, (Eastern Zhou dynasty, Spring and Autumn period, 770–ca. 470 bc) Bronze, h. 23.0 cm., w. 27.0 cm., d. 21.0 cm. (9 1/16 × 10 5/8 × 8 1/4 in.). Museum purchase from the C.D. Carter Collection, by subscription. y1965-24 a-b. Photo: © Princeton University Art Museum, Image courtesy of Princeton University Art Museum. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Ideology of power and power of ideology in early China / edited by Yuri Pines, Paul R. Goldin, Martin Kern. pages cm. -- (Sinica Leidensia, ISSN 0169-9563 ; volume 124) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-90-04-29929-0 (hardback : acid-free paper) -- ISBN 978-90-04-29933-7 (e-book) 1. Political science--China--History--To 1500. 2. Power (Social sciences)--China--History-- To 1500. 3. Ideology--Political aspects--China--History--To 1500. 4. Political culture--China-- History--To 1500. 5. China--Politics and government--To 221 B.C. 6. China--Politics and government--221 B.C.-960 A.D. -

Economic Cycles in Ancient China

NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES ECONOMIC CYCLES IN ANCIENT CHINA Yaguang Zhang Guo Fan John Whalley Working Paper 21672 http://www.nber.org/papers/w21672 NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 October 2015 This paper is the second of a planned series examining the Chinese history of ancient economic thought in light of later Western thought. The first paper is Monetary Theory and Policy from a Chinese Historical Perspective which has been published in China Economic Review (Volume 26, September 2013, Pages 89-104.) This work is of importance in better understanding the Chinese policy response to the global issues of the day; the financial crisis, global warming and climate change. We acknowledge financial support from the Ontario Research Fund (ORF-F3), IDRC, and the Centre for International Governance Innovation (CIGI), Waterloo Ontario. The views expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Bureau of Economic Research. NBER working papers are circulated for discussion and comment purposes. They have not been peer- reviewed or been subject to the review by the NBER Board of Directors that accompanies official NBER publications. © 2015 by Yaguang Zhang, Guo Fan, and John Whalley. All rights reserved. Short sections of text, not to exceed two paragraphs, may be quoted without explicit permission provided that full credit, including © notice, is given to the source. Economic Cycles in Ancient China Yaguang Zhang, Guo Fan, and John Whalley NBER Working Paper No. 21672 October 2015 JEL No. N1,N15 ABSTRACT We discuss business cycles in ancient China. -

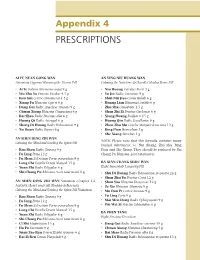

Appendix 4 PRESCRIPTIONS

Appendix 4 PRESCRIPTIONS AI FU NUAN GONG WAN AN YING NIU HUANG WAN Artemisia-Cyperus Warming the Uterus Pill Calming the Nutritive-Qi [Level] Calculus Bovis Pill • Ai Ye Folium Artemisiae argyi 9 g • Niu Huang Calculus Bovis 3 g • Wu Zhu Yu Fructus Evodiae 4.5 g • Yu Jin Radix Curcumae 9 g • Rou Gui Cortex Cinnamomi 4.5 g • Shui Niu Jiao Cornu Bubali 6 g • Xiang Fu Rhizoma Cyperi 9 g • Huang Lian Rhizoma Coptidis 6 g • Dang Gui Radix Angelicae sinensis 9 g • Zhu Sha Cinnabaris 1.5 g • Chuan Xiong Rhizoma Chuanxiong 6 g • Shan Zhi Zi Fructus Gardeniae 6 g • Bai Shao Radix Paeoniae alba 6 g • Xiong Huang Realgar 0.15 g • Huang Qi Radix Astragali 6 g • Huang Qin Radix Scutellariae 9 g • Sheng Di Huang Radix Rehmanniae 9 g • Zhen Zhu Mu Concha Margatiriferae usta 12 g • Xu Duan Radix Dipsaci 6 g • Bing Pian Borneolum 3 g • She Xiang Moschus 1 g AN SHEN DING ZHI WAN NOTE: Please note that this formula contains many Calming the Mind and Settling the Spirit Pill banned substances, i.e. Niu Huang, Zhu Sha, Bing • Ren Shen Radix Ginseng 9 g Pian and She Xiang. They should be replaced by Shi • Fu Ling Poria 12 g Chang Pu Rhizoma Acori tatarinowii. • Fu Shen Sclerotium Poriae pararadicis 9 g • Long Chi Fossilia Dentis Mastodi 15 g BA XIAN CHANG SHOU WAN • Yuan Zhi Radix Polygalae 6 g Eight Immortals Longevity Pill • Shi Chang Pu Rhizoma Acori tatarinowii 8 g • Shu Di Huang Radix Rehmanniae preparata 24 g • Shan Zhu Yu Fructus Corni 12 g AN SHEN DING ZHI WAN Variation (Chapter 14, • Shan Yao Rhizoma Dioscoreae 12 g Anxiety, Heart and Gall Bladder -

A Failed Peripheral Hegemonic State with a Limited Mandate of Heaven: Politico-Historical Reflections of a ∗ Survivor of the Southern Tang

DOI: 10.6503/THJCS.201806_48(2).0002 A Failed Peripheral Hegemonic State with a Limited Mandate of Heaven: Politico-Historical Reflections of a ∗ Survivor of the Southern Tang Li Cho-ying∗∗ Institute of History National Tsing Hua University ABSTRACT This article focuses on the concepts the Diaoji litan 釣磯立談 author, a survivor of the Southern Tang, developed to understand the history of the kingdom. It discusses his historical discourse and shows that one of its purposes was to secure a legitimate place in history for the Southern Tang. The author developed a crucial concept, the “peripheral hegemonic state” 偏霸, to comprehend its history. This concept contains an idea of a limited mandate of heaven, a geopolitical analysis of the Southern Tang situation, and a plan for the kingdom to compete with its rivals for the supreme political authority over all under heaven. With this concept, the Diaoji author implicitly disputes official historiography’s demeaning characterization of the Southern Tang as “pseudo” 偽, and founded upon “usurpation” 僭 and “thievery” 竊. He condemns the second ruler, Li Jing 李璟 (r. 943-961) and several ministers for abandoning the first ruler Li Bian’s 李 (r. 937-943) plan, thereby leading the kingdom astray. The work also stresses the need to recruit authentic Confucians to administer the government. As such, this article argues that the Diaoji should be understood as a politico-historical book of the late tenth century. Key words: Southern Tang, survivor, Diaoji litan 釣磯立談, peripheral hegemonic state, mandate of heaven ∗ The author thanks Professors Charles Hartman, Liang Ken-yao 梁庚堯, and the two anonymous reviewers for their thoughtful comments. -

340336 1 En Bookbackmatter 251..302

A List of Historical Texts 《安禄山事迹》 《楚辭 Á 招魂》 《楚辭注》 《打馬》 《打馬格》 《打馬錄》 《打馬圖經》 《打馬圖示》 《打馬圖序》 《大錢圖錄》 《道教援神契》 《冬月洛城北謁玄元皇帝廟》 《風俗通義 Á 正失》 《佛说七千佛神符經》 《宮詞》 《古博經》 《古今圖書集成》 《古泉匯》 《古事記》 《韓非子 Á 外儲說左上》 《韓非子》 《漢書 Á 武帝記》 《漢書 Á 遊俠傳》 《和漢古今泉貨鑒》 《後漢書 Á 許升婁傳》 《黃帝金匱》 《黃神越章》 《江南曲》 《金鑾密记》 《經國集》 《舊唐書 Á 玄宗本紀》 《舊唐書 Á 職官志 Á 三平准令條》 《開元別記》 © Springer Science+Business Media Singapore 2016 251 A.C. Fang and F. Thierry (eds.), The Language and Iconography of Chinese Charms, DOI 10.1007/978-981-10-1793-3 252 A List of Historical Texts 《開元天寶遺事 Á 卷二 Á 戲擲金錢》 《開元天寶遺事 Á 卷三》 《雷霆咒》 《類編長安志》 《歷代錢譜》 《歷代泉譜》 《歷代神仙通鑑》 《聊斋志異》 《遼史 Á 兵衛志》 《六甲祕祝》 《六甲通靈符》 《六甲陰陽符》 《論語 Á 陽貨》 《曲江對雨》 《全唐詩 Á 卷八七五 Á 司馬承禎含象鑒文》 《泉志 Á 卷十五 Á 厭勝品》 《勸學詩》 《群書類叢》 《日本書紀》 《三教論衡》 《尚書》 《尚書考靈曜》 《神清咒》 《詩經》 《十二真君傳》 《史記 Á 宋微子世家 Á 第八》 《史記 Á 吳王濞列傳》 《事物绀珠》 《漱玉集》 《說苑 Á 正諫篇》 《司馬承禎含象鑒文》 《私教類聚》 《宋史 Á 卷一百五十一 Á 志第一百四 Á 輿服三 Á 天子之服 皇太子附 后妃之 服 命婦附》 《宋史 Á 卷一百五十二 Á 志第一百五 Á 輿服四 Á 諸臣服上》 《搜神記》 《太平洞極經》 《太平廣記》 《太平御覽》 《太上感應篇》 《太上咒》 《唐會要 Á 卷八十三 Á 嫁娶 Á 建中元年十一月十六日條》 《唐兩京城坊考 Á 卷三》 《唐六典 Á 卷二十 Á 左藏令務》 《天曹地府祭》 A List of Historical Texts 253 《天罡咒》 《通志》 《圖畫見聞志》 《退宮人》 《萬葉集》 《倭名类聚抄》 《五代會要 Á 卷二十九》 《五行大義》 《西京雜記 Á 卷下 Á 陸博術》 《仙人篇》 《新唐書 Á 食貨志》 《新撰陰陽書》 《續錢譜》 《續日本記》 《續資治通鑑》 《延喜式》 《顏氏家訓 Á 雜藝》 《鹽鐵論 Á 授時》 《易經 Á 泰》 《弈旨》 《玉芝堂談薈》 《元史 Á 卷七十八 Á 志第二十八 Á 輿服一 儀衛附》 《雲笈七籖 Á 卷七 Á 符圖部》 《雲笈七籖 Á 卷七 Á 三洞經教部》 《韻府帬玉》 《戰國策 Á 齊策》 《直齋書錄解題》 《周易》 《莊子 Á 天地》 《資治通鑒 Á 卷二百一十六 Á 唐紀三十二 Á 玄宗八載》 《資治通鑒 Á 卷二一六 Á 唐天寶十載》 A Chronology of Chinese Dynasties and Periods ca.