Liberation at the Crossroads: Where Divinity and Humanity Embrace

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Latin America and Liberation Theology

Comparative Civilizations Review Volume 49 Number 49 Fall 2003 Article 7 10-1-2003 Latin America and Liberation Theology Dong Sull Choi Brigham Young University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/ccr Recommended Citation Choi, Dong Sull (2003) "Latin America and Liberation Theology," Comparative Civilizations Review: Vol. 49 : No. 49 , Article 7. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/ccr/vol49/iss49/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Comparative Civilizations Review by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Choi: Latin America and Liberation Theology 76 Comparative Civilizations Review No. 49 LATIN AMERICA AND LIBERATION THEOLOGY DONG SULL CHOI, BRIGHAM YOUNG UNIVERSITY A central and fundamental theme in most world religions is libera- tion. Hinduism, Buddhism, Jainism, and Sikhism all seek liberation from the endless cycles of birth and death until the adherents attain mok- sha, nirvana, or self-realization. Monotheistic faiths, such as Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, promise and teach liberation from oppression, sin, and the fear of death. Biblical traditions and messages, including the story of the Israelites' flight from Egyptian bondage, have been the important historical sources or foundations for various searches for lib- eration. The rise of "liberation theology" in the Christian world is one of the most conspicuous and significant developments of the past several decades in this global village. Regarded by some theologians as the most important religious movement since the Protestant Reformation of the 16th century, liberation theology characterizes a variety of Christian movements in many parts of the world, including Asia, Africa, Western Europe, North America, and especially Latin America. -

Karl Rahner and Liberation Theology

KARL RAHNER AND LIBERATION THEOLOGY Jon Sobrino URING THE 1970s, A NEW CHURCH AND A NEW THEOLOGY arose in DLatin America. This article is a personal reflection on what Karl Rahner has meant for me in that context, though I hope that what I say will apply to liberation theology more broadly. I write out of the life-experience in El Salvador that has led me to read with new eyes the theology I had previously studied, in which Rahner’s work was a very important element. I am also writing out of my close personal and intellectual relationship with Ignacio Ellacuría, Rahner’s student in Innsbruck between 1958 and 1962. On account of his defence of faith and justice, Ellacuría, as many will know, was murdered on 16 November 1989, along with five other Jesuits and two female workers from the university in which he taught. But we should remember that Ellacuría was not just Rahner’s pupil. He took forward important ideas in Rahner’s theology, as he sought to express them in his own historical situation and in a way appropriate for the world of the poor. This article begins with an account of Rahner’s attitude towards the new things that were happening ecclesially and theologically in Latin America during the last years of his life. Then I shall try to explore Rahner’s influence on liberation theology. The Demands of a New Situation In an interview he gave to a Spanish magazine shortly before his death, Rahner was asked what he thought about the current state of the Church. -

A Pope of Their Own

Magnus Lundberg A Pope of their Own El Palmar de Troya and the Palmarian Church UPPSALA STUDIES IN CHURCH HISTORY 1 About the series Uppsala Studies in Church History is a series that is published in the Department of Theology, Uppsala University. The series includes works in both English and Swedish. The volumes are available open-access and only published in digital form. For a list of available titles, see end of the book. About the author Magnus Lundberg is Professor of Church and Mission Studies and Acting Professor of Church History at Uppsala University. He specializes in early modern and modern church and mission history with focus on colonial Latin America. Among his monographs are Mission and Ecstasy: Contemplative Women and Salvation in Colonial Spanish America and the Philippines (2015) and Church Life between the Metropolitan and the Local: Parishes, Parishioners and Parish Priests in Seventeenth-Century Mexico (2011). Personal web site: www.magnuslundberg.net Uppsala Studies in Church History 1 Magnus Lundberg A Pope of their Own El Palmar de Troya and the Palmarian Church Lundberg, Magnus. A Pope of Their Own: Palmar de Troya and the Palmarian Church. Uppsala Studies in Church History 1.Uppsala: Uppsala University, Department of Theology, 2017. ISBN 978-91-984129-0-1 Editor’s address: Uppsala University, Department of Theology, Church History, Box 511, SE-751 20 UPPSALA, Sweden. E-mail: [email protected]. Contents Preface 1 1. Introduction 11 The Religio-Political Context 12 Early Apparitions at El Palmar de Troya 15 Clemente Domínguez and Manuel Alonso 19 2. -

The Holy See (Including Vatican City State)

COMMITTEE OF EXPERTS ON THE EVALUATION OF ANTI-MONEY LAUNDERING MEASURES AND THE FINANCING OF TERRORISM (MONEYVAL) MONEYVAL(2012)17 Mutual Evaluation Report Anti-Money Laundering and Combating the Financing of Terrorism THE HOLY SEE (INCLUDING VATICAN CITY STATE) 4 July 2012 The Holy See (including Vatican City State) is evaluated by MONEYVAL pursuant to Resolution CM/Res(2011)5 of the Committee of Ministers of 6 April 2011. This evaluation was conducted by MONEYVAL and the report was adopted as a third round mutual evaluation report at its 39 th Plenary (Strasbourg, 2-6 July 2012). © [2012] Committee of experts on the evaluation of anti-money laundering measures and the financing of terrorism (MONEYVAL). All rights reserved. Reproduction is authorised, provided the source is acknowledged, save where otherwise stated. For any use for commercial purposes, no part of this publication may be translated, reproduced or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic (CD-Rom, Internet, etc) or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or any information storage or retrieval system without prior permission in writing from the MONEYVAL Secretariat, Directorate General of Human Rights and Rule of Law, Council of Europe (F-67075 Strasbourg or [email protected] ). 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. PREFACE AND SCOPE OF EVALUATION............................................................................................ 5 II. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY....................................................................................................................... -

Solidarity As Spiritual Exercise: a Contribution to the Development of Solidarity in the Catholic Social Tradition

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by eScholarship@BC Solidarity as spiritual exercise: a contribution to the development of solidarity in the Catholic social tradition Author: Mark W. Potter Persistent link: http://hdl.handle.net/2345/738 This work is posted on eScholarship@BC, Boston College University Libraries. Boston College Electronic Thesis or Dissertation, 2009 Copyright is held by the author, with all rights reserved, unless otherwise noted. Boston College The Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Department of Theology SOLIDARITY AS SPIRITUAL EXERCISE: A CONTRIBUTION TO THE DEVELOPMENT OF SOLIDARITY IN THE CATHOLIC SOCIAL TRADITION a dissertation by MARK WILLIAM POTTER submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy August 2009 © copyright by MARK WILLIAM POTTER 2009 Solidarity as Spiritual Exercise: A Contribution to the Development of Solidarity in the Catholic Social Tradition By Mark William Potter Director: David Hollenbach, S.J. ABSTRACT The encyclicals and speeches of Pope John Paul II placed solidarity at the very center of the Catholic social tradition and contemporary Christian ethics. This disserta- tion analyzes the historical development of solidarity in the Church’s encyclical tradition, and then offers an examination and comparison of the unique contributions of John Paul II and the Jesuit theologian Jon Sobrino to contemporary understandings of solidarity. Ultimately, I argue that understanding solidarity as spiritual exercise integrates the wis- dom of John Paul II’s conception of solidarity as the virtue for an interdependent world with Sobrino’s insights on the ethical implications of Christian spirituality, orthopraxis, and a commitment to communal liberation. -

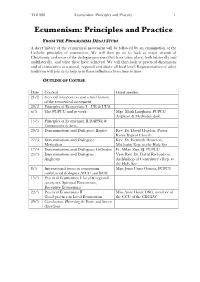

Ecumenism, Principles and Practice

TO1088 Ecumenism: Principles and Practice 1 Ecumenism: Principles and Practice FROM THE PROGRAMMA DEGLI STUDI A short history of the ecumenical movement will be followed by an examination of the Catholic principles of ecumenism. We will then go on to look at major strands of Christianity and some of the dialogue processes that have taken place, both bilaterally and multilaterally, and what these have achieved. We will then look at practical dimensions and of ecumenism at national, regional and above all local level. Representatives of other traditions will join us to help us in these reflections from time to time. OUTLINE OF COURSE Date Content Guest speaker 21/2 General introduction and a brief history of the ecumenical movement 28/2 Principles of Ecumenism I – UR & UUS 6/3 The PCPCU and its work Mgr. Mark Langham, PCPCU Anglican & Methodist desk. 13/3 Principles of Ecumenism II DAPNE & Communicatio in Sacris 20/3 Denominations and Dialogues: Baptist Rev. Dr. David Hogdon, Pastor, Rome Baptist Church. 27/3 Denominations and Dialogues: Rev. Dr. Kenneth Howcroft, Methodists Methodist Rep. to the Holy See 17/4 Denominations and Dialogues: Orthodox Fr. Milan Zust SJ, PCPCU 24/4 Denominations and Dialogues : Very Rev. Dr. David Richardson, Anglicans Archbishop of Canterbury‘s Rep. to the Holy See 8/5 International issues in ecumenism, Mgr. Juan Usma Gomez, PCPCU multilateral dialogues ,WCC and BEM 15/5 Practical Ecumenism I: local & regional structures, Spiritual Ecumenism, Receptive Ecumenism 22/5 Practical Ecumenism II Miss Anne Doyle DSG, member of Good practice in Local Ecumenism the CCU of the CBCEW 29/5 Conclusion: Harvesting the Fruits and future directions TO1088 Ecumenism: Principles and Practice 2 Ecumenical Resources CHURCH DOCUMENTS Second Vatican Council Unitatis Redentigratio (1964) PCPCU Directory for the Application of the Principles and Norms of Ecumenism (1993) Pope John Paul II Ut Unum Sint. -

The Promise of the New Ecumenical Directory

Theological Studies Faculty Works Theological Studies 1994 The Promise of the New Ecumenical Directory Thomas P. Rausch Loyola Marymount University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/theo_fac Part of the Catholic Studies Commons Recommended Citation Rausch, Thomas P. “The Promise of the New Ecumenical Directory,” Mid-Stream 33 (1994): 275-288. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Theological Studies at Digital Commons @ Loyola Marymount University and Loyola Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theological Studies Faculty Works by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Loyola Marymount University and Loyola Law School. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Thomas P. Rausch The Promise of the ew Ecumenical Directory Thomas P. Rausch, S. J., is Professor of Theological Studies and Rector of the Jesuit Community at Loyola Marym01.1nt University, Los Angeles, California, and chair of the department. A specialist in the areas of ecclesiology, ecumenism, and the theology of the priesthood, he is the author of five books and numerous articles. he new Roman Catholic Ecumenical Directory (ED), officially titled the Directory for the Application ofPrinciples and Norms on Ecumenism, was released on June 8, 1993 by the Pontifical Council for Promoting Christian Unity. 1 In announcing it, Pope John Paul II said that its preparation was motivated by "the desire to hasten the journey towards unity, an indispensable condition for a truly re newed evangelization. "2 The pope's linking of Christian unity with a renewal of the Church's work of evangelization is important, for the very witness of the Church as a community of humankind reconciled in Christ is weakened by the obvious lack of unity among Christians. -

Getting Back to Idolatry Critique: Kingdom, Kin-Dom, and the Triune

86 87 Getting Back to Idolatry Critique: Kingdom, Critical theory’s concept of ideology is helpful, but when it flattens the idolatry critique by identifying idolatry as ideology, and thus making them synonymous, Kin-dom, and the Triune Gift Economy ideology ultimately replaces idolatry.4 I suspect that ideology here passes for dif- fering positions within sheer immanence, and therefore unable to produce a “rival David Horstkoetter universality” to global capitalism.5 Therefore I worry that the political future will be a facade of sheer immanence dictating action read as competing ideologies— philosophical positions without roots—under the universal market.6 Ideology is thus made subject to the market’s antibodies, resulting in the market commodi- Liberation theology has largely ceased to develop critiques of idolatry, espe- fying ideology. The charge of idolatry, however, is rooted in transcendence (and cially in the United States. I will argue that the critique is still viable in Christian immanence), which is at the very least a rival universality to global capitalism; the theology and promising for the future of liberation theology, by way of reformu- critique of idolatry assumes divine transcendence and that the incarnational, con- lating Ada María Isasi-Díaz’s framework of kin-dom within the triune economy. structive project of divine salvation is the map for concrete, historical work, both Ultimately this will mean reconsidering our understanding of and commitment to constructive and critical. This is why, when ideology is the primary, hermeneutical divinity and each other—in a word, faith.1 category, I find it rather thin, unconvincing, and unable to go as far as theology.7 The idea to move liberation theology from theology to other disciplines Also, although sociological work is necessary, I am not sure that it is primary for drives discussion in liberation theology circles, especially in the US, as we talk realizing divine work in history. -

"For Yours Is the Kingdom of God": a Historical Analysis of Liberation Theology in the Last Two Decades and Its Significance Within the Christian Tradition

W&M ScholarWorks Undergraduate Honors Theses Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 5-2009 "For Yours is the Kingdom of God": A historical analysis of liberation theology in the last two decades and its significance within the Christian tradition Virginia Irby College of William and Mary Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses Part of the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Irby, Virginia, ""For Yours is the Kingdom of God": A historical analysis of liberation theology in the last two decades and its significance within the Christian tradition" (2009). Undergraduate Honors Theses. Paper 288. https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses/288 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “For Yours is the Kingdom of God:” A historical analysis of liberation theology in the last two decades and its significance within the Christian tradition A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Bachelors of Arts in Religious Studies from The College of William and Mary by Virginia Kathryn Irby Accepted for ___________________________________ (Honors, High Honors, Highest Honors) ________________________________________ John S. Morreall, Director ________________________________________ Julie G. Galambush ________________________________________ Tracy T. Arwari Williamsburg, VA April 29, 2009 This thesis is dedicated to all those who have given and continue to give their lives to the promotion and creation of justice and peace for all people. -

Theology Is Everywhere 2.5 - the Gospel of Liberation 1

Theology is Everywhere 2.5 - The Gospel of Liberation 1. Galatians – the Gospel of Liberation 5 1 For freedom Christ has set us free. Stand firm, therefore, and do not submit again to a yoke of slavery. 13 For you were called to freedom, brothers and sisters;[c] only do not use your freedom as an opportunity for self-indulgence,[d] but through love become slaves to one another. 14 For the whole law is summed up in a single commandment, “You shall love your neighbor as yourself.” 2. God’s Preferential Option for the Poor This referred especially to a trend throughout biblical texts, where there is a demonstrable preference given to powerless individuals who live on the margins of society. citing Matthew 25, “Whatever you did for the least of these, you did for me.” 3. Gustavo Gutierrez ~ A Theology of Liberation “But the poor person does not exist as an inescapable fact of destiny. His or her existence is not politically neutral, and it is not ethically innocent. The poor are a by-product of the system in which we live and for which we are responsible. They are marginalized by our social and cultural world. They are the oppressed, exploited proletariat, robbed of the fruit of their labor and despoiled of their humanity. Hence the poverty of the poor is not a call to generous relief action, but a demand that we go and build a different social order.” 4. The Universality of God’s Preference 5. De-centralized Christianity 6. Viewing Scripture from the Vantage point of the Poor 7. -

Stories of Minjung Theology

International Voices in Biblical Studies STORIES OF MINJUNG THEOLOGY STORIES This translation of Asian theologian Ahn Byung-Mu’s autobiography combines his personal story with the history of the Korean nation in light of the dramatic social, political, and cultural upheavals of the STORIES OF 1970s. The book records the history of minjung (the people’s) theology that emerged in Asia and Ahn’s involvement in it. Conversations MINJUNG THEOLOGY between Ahn and his students reveal his interpretations of major Christian doctrines such as God, sin, Jesus, and the Holy Spirit from The Theological Journey of Ahn Byung‑Mu the minjung perspective. The volume also contains an introductory essay that situates Ahn’s work in its context and discusses the place in His Own Words and purpose of minjung hermeneutics in a vastly different Korea. (1922–1996) was professor at Hanshin University, South Korea, and one of the pioneers of minjung theology. He was imprisonedAHN BYUNG-MU twice for his political views by the Korean military government. He published more than twenty books and contributed more than a thousand articles and essays in Korean. His extended work in English is Jesus of Galilee (2004). In/Park Electronic open access edition (ISBN 978-0-88414-410-6) available at http://ivbs.sbl-site.org/home.aspx Translated and edited by Hanna In and Wongi Park STORIES OF MINJUNG THEOLOGY INTERNATIONAL VOICES IN BIBLICAL STUDIES Jione Havea, General Editor Editorial Board: Jin Young Choi Musa W. Dube David Joy Aliou C. Niang Nasili Vaka’uta Gerald O. West Number 11 STORIES OF MINJUNG THEOLOGY The Theological Journey of Ahn Byung-Mu in His Own Words Translated by Hanna In. -

Political and Liberation Theology Is the First of Our Tasks in These Pages

224 THEOLOGICAL TRENDS Political and liberation theology, I LTHOUGH only a few years ago it would have seemed questionable A at the least to discuss political and liberation theology side by side, today it would make no sense at all to do otherwise. Part of their respective maturation processes has been to learn from one another; to learn about their essentially similar intentions and the differences in their respective approaches to that common purpose, namely, to demonstrate the closeness of the link between political action and christian life. In recent years, the theology of liberation has definitely been the better- known phenomenon, no doubt as exaggerated media coverage about Marxism and the theology of revolution has found it more newsworthy. However, the term 'political theology' has much the longer pedigree. 'Liberation theology' as a term, if not as a reality, dates back only as far as the mid-sixties, and first became current with Gustavo Gutierrez's A theology of liberation. 1 'Political theology', on the other hand, is as old as the threefold stoic division of theology into natural, mythical and political. 2 To delineate the precise contemporary relationship between political and liberation theology is the first of our tasks in these pages. In 1977 and 1978 in the pages of The Way, Joseph Laishley wrote a three-part article on liberation theology. The present two-part article is not to be thought to duplicate or replace that valuable work, but to bring it up to date. Seven or eight years later, it is possible to see far more clearly the relationship of political and liberation theologies, and, of course, a lot has happened in these years to both theological schools.