Solidarity As Spiritual Exercise: a Contribution to the Development of Solidarity in the Catholic Social Tradition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Spiritan Missionaries: Precursors of Inculturation Theology

Spiritan Horizons Volume 14 Issue 14 Article 13 Fall 2019 Spiritan Missionaries: Precursors of Inculturation Theology Bede Uche Ukwuije Follow this and additional works at: https://dsc.duq.edu/spiritan-horizons Part of the Catholic Studies Commons Recommended Citation Ukwuije, B. U. (2019). Spiritan Missionaries: Precursors of Inculturation Theology. Spiritan Horizons, 14 (14). Retrieved from https://dsc.duq.edu/spiritan-horizons/vol14/iss14/13 This Soundings is brought to you for free and open access by the Spiritan Collection at Duquesne Scholarship Collection. It has been accepted for inclusion in Spiritan Horizons by an authorized editor of Duquesne Scholarship Collection. Bede Uche Ukwuije, C.S.Sp. Spiritan Missionaries as Precursors of Inculturation Theology in West Africa: With Particular Reference to the Translation of Church Documents into Vernacular Languages 1 Bede Uche Ukwuije, C.S.Sp. Introduction Bede Uche Ukwuije, C.S.Sp., is Recent studies based on documents available in the First Assistant to the Superior archives of missionary congregations have helped to arrive General and member of the at a positive appreciation of the contribution of the early Theological Commission of the missionaries to the development of African cultures.2 This Union of Superiors General, Rome. He holds a Doctorate presentation will center on the work done by Spiritans in in Theology (Th.D.) from some West African countries, especially in the production the Institut Catholique de of dictionaries and grammar books and the translation of Paris and a Ph.D. in Theology the Bible and church documents into vernacular languages. and Religious Studies from Contrary to the widespread idea that the early missionaries the Catholic University of destroyed African cultures (the tabula rasa theory), this Leuven, Belgium. -

The Holy See

The Holy See APOSTOLIC LETTER MANE NOBISCUM DOMINE OF THE HOLY FATHER JOHN PAUL II TO THE BISHOPS, CLERGY AND FAITHFUL FOR THE YEAR OF THE EUCHARIST OCTOBER 2004–OCTOBER 2005 INTRODUCTION 1. “Stay with us, Lord, for it is almost evening” (cf. Lk 24:29). This was the insistent invitation that the two disciples journeying to Emmaus on the evening of the day of the resurrection addressed to the Wayfarer who had accompanied them on their journey. Weighed down with sadness, they never imagined that this stranger was none other than their Master, risen from the dead. Yet they felt their hearts burning within them (cf. v. 32) as he spoke to them and “explained” the Scriptures. The light of the Word unlocked the hardness of their hearts and “opened their eyes” (cf. v. 31). Amid the shadows of the passing day and the darkness that clouded their spirit, the Wayfarer brought a ray of light which rekindled their hope and led their hearts to yearn for the fullness of light. “Stay with us”, they pleaded. And he agreed. Soon afterwards, Jesus' face would disappear, yet the Master would “stay” with them, hidden in the “breaking of the bread” which had opened their eyes to recognize him. 2. The image of the disciples on the way to Emmaus can serve as a fitting guide for a Year when the Church will be particularly engaged in living out the mystery of the Holy Eucharist. Amid our questions and difficulties, and even our bitter disappointments, the divine Wayfarer continues to walk at our side, opening to us the Scriptures and leading us to a deeper understanding of the 2 mysteries of God. -

Jenkins to Fucinaro

+ JHS Vaticano 8 abril 2016 Querido hermano: Invocando la protección de la Sagrada Familia de Nazaret, me complazco de enviarle mi Exhortación “Amoris laetitia” por el bien de todas las familias y de todas las personas, jóvenes y ancianas, confiadas a su ministerio pastoral. Unidos en el Señor Jesús, con María y José, le pido que no se olvide de rezar por mí. Franciscus Texto de la Exhortación Apostólica: https://vaticloud.vatican.va/oc/public.php?service=files&t=bc83e4a00366ce2ddfa6be593a406d2e Materiales adicionales: 1- Síntesis: https://vaticloud.vatican.va/oc/public.php?service=files&t=23ba69811e9d948dd8e2c6d98077e465 2- Preguntas y respuestas: https://vaticloud.vatican.va/oc/public.php?service=files&t=c9c9f260b4e8bfea60ab29d2a2fbbfda Síntesis Amoris laetitia, sobre el amor en la familia “Amoris laetitia” (AL – “La alegría del amor”), la Exhortación apostólica post-sinodal “sobre el amor en la familia”, con fecha no casual del 19 de marzo, Solemnidad de San José, recoge los resultados de dos Sínodos sobre la familia convocados por Papa Francisco en el 2014 y en el 2015, cuyas Relaciones conclusivas son largamente citadas, junto a los documentos y enseñanzas de sus Predecesores y a las numerosas catequesis sobre la familia del mismo Papa Francisco. Todavía, como ya ha sucedido en otros documentos magisteriales, el Papa hace uso también de las contribuciones de diversas Conferencias episcopales del mundo (Kenia, Australia, Argentina…) y de citaciones de personalidades significativas como Martin Luther King o Eric Fromm. Es particular una citación de la película “La fiesta de Babette”, que el Papa recuerda para explicar el concepto de gratuidad. Premisa La Exhortación apostólica impresiona por su amplitud y articulación. -

Karl Rahner and Liberation Theology

KARL RAHNER AND LIBERATION THEOLOGY Jon Sobrino URING THE 1970s, A NEW CHURCH AND A NEW THEOLOGY arose in DLatin America. This article is a personal reflection on what Karl Rahner has meant for me in that context, though I hope that what I say will apply to liberation theology more broadly. I write out of the life-experience in El Salvador that has led me to read with new eyes the theology I had previously studied, in which Rahner’s work was a very important element. I am also writing out of my close personal and intellectual relationship with Ignacio Ellacuría, Rahner’s student in Innsbruck between 1958 and 1962. On account of his defence of faith and justice, Ellacuría, as many will know, was murdered on 16 November 1989, along with five other Jesuits and two female workers from the university in which he taught. But we should remember that Ellacuría was not just Rahner’s pupil. He took forward important ideas in Rahner’s theology, as he sought to express them in his own historical situation and in a way appropriate for the world of the poor. This article begins with an account of Rahner’s attitude towards the new things that were happening ecclesially and theologically in Latin America during the last years of his life. Then I shall try to explore Rahner’s influence on liberation theology. The Demands of a New Situation In an interview he gave to a Spanish magazine shortly before his death, Rahner was asked what he thought about the current state of the Church. -

Rosarium Virginis Mariae of the Supreme Pontiff John Paul Ii to the Bishops, Clergy and Faithful on the Most Holy Rosary

The Holy See APOSTOLIC LETTER ROSARIUM VIRGINIS MARIAE OF THE SUPREME PONTIFF JOHN PAUL II TO THE BISHOPS, CLERGY AND FAITHFUL ON THE MOST HOLY ROSARY INTRODUCTION 1. The Rosary of the Virgin Mary, which gradually took form in the second millennium under the guidance of the Spirit of God, is a prayer loved by countless Saints and encouraged by the Magisterium. Simple yet profound, it still remains, at the dawn of this third millennium, a prayer of great significance, destined to bring forth a harvest of holiness. It blends easily into the spiritual journey of the Christian life, which, after two thousand years, has lost none of the freshness of its beginnings and feels drawn by the Spirit of God to “set out into the deep” (duc in altum!) in order once more to proclaim, and even cry out, before the world that Jesus Christ is Lord and Saviour, “the way, and the truth and the life” (Jn 14:6), “the goal of human history and the point on which the desires of history and civilization turn”.(1) The Rosary, though clearly Marian in character, is at heart a Christocentric prayer. In the sobriety of its elements, it has all the depth of the Gospel message in its entirety, of which it can be said to be a compendium.(2) It is an echo of the prayerof Mary, her perennial Magnificat for the work of the redemptive Incarnation which began in her virginal womb. With the Rosary, the Christian people sits at the school of Mary and is led to contemplate the beauty on the face of Christ and to experience the depths of his love. -

Mary and Inter-Religious Dialogue 1/20/15 1:31 PM

Mary and Inter-religious Dialogue 1/20/15 1:31 PM With Vatican II’s “Declaration on the relation of the Church to Non-Christian Religions Nostra Aetate” (NA) [link to: http://www.vatican.va/archive/hist_councils/ii_vatican_council/documents/vat- ii_decl_19651028_nostra-aetate_en.html of October 28, 1965 the Catholic Church has initiated her move toward other faiths by means of interreligious dialogue. The keyword ‘dialogue’ is important in this context since it applies to all cultures as well as faith traditions and respects the need for Inculturation. Moreover, NA explains that true dialogue “regards with sincere reverence those ways of conduct and of life, those precepts and teachings which, though differing in many aspects from the ones she holds and sets forth, nonetheless often reflect a ray of that Truth which enlightens all people (NA, 2). The effect of these encounters become increasingly apparent and is manifested by authentic esteem for the values and convictions in each religion. We can also observe a genuine exploration of common values as well as solicitude for the betterment of living conditions on earth. To foster the work of dialogue, Pope Paul VI set up the Secretariat for Non-Christians in 1964, recently renamed the Pontifical Council for Interreligious Dialogue. In 1991, to commemorate the twenty-fifth anniversary of NA, the Pontifical Council for Inter-Religious Dialogue promulgated the document Dialogue and Proclamation–Reflection and Orientations on Interreligious Dialogue and the Proclamation of the Gospel of Jesus Christ. http://www.vatican.va/roman_curia/pontifical_councils/interelg/documents/rc_pc_interelg_doc_19051991_ dialogue-and-proclamatio_en.html] It highlights four forms of interreligious dialogue without claiming to establish any order of priority among them: a) The dialogue of life, where people strive to live in an open and neighborly spirit, sharing their joys and sorrows, their human problems and preoccupations. -

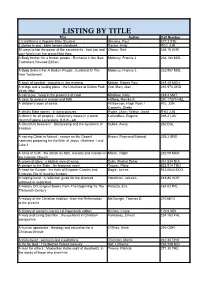

Parish Library Listing

LISTING BY TITLE Title Author Call Number 2 Corinthians (Lifeguide Bible Studies) Stevens, Paul 227.3 STE 3 stories in one : bible heroes storybook Rector, Andy REC JUN 50 ways to tap the power of the sacraments : how you and Ghezzi, Bert 234.16 GHE your family can live grace-filled lives A Body broken for a broken people : Eucharist in the New Moloney, Francis J. 234.163 MOL Testament Revised Edition A Body Broken For A Broken People : Eucharist In The Moloney, Francis J. 232.957 MOL New Testament A book of comfort : thoughts in late evening Mohan, Robert Paul 248.48 MOH A bridge and a resting place : the Ursulines at Dutton Park Ord, Mary Joan 255.974 ORD 1919-1980 A call to joy : living in the presence of God Matthew, Kelly 248.4 MAT A case for peace in reason and faith Hellwig, Monika K. 291.17873 HEL A children's book of saints Williamson, Hugh Ross / WIL JUN Connelly, Sheila A child's Bible stories : in living pictures Ryder, Lilian / Walsh, David RYD JUN A church for all peoples : missionary issues in a world LaVerdiere, Eugene 266.2 LAV church Eugene LaVerdiere, S.S.S - edi A Church to believe in : Discipleship and the dynamics of Dulles, Avery 262 DUL freedom A coming Christ in Advent : essays on the Gospel Brown, Raymond Edward 226.2 BRO narritives preparing for the Birth of Jesus : Matthew 1 and Luke 1 A crisis of truth - the attack on faith, morality and mission in Martin, Ralph 282.09 MAR the Catholic Church A crown of glory : a biblical view of aging Dulin, Rachel Zohar 261.834 DUL A danger to the State : An historical novel Trower, Philip 823.914 TRO A heart for Europe : the lives of Emporer Charles and Bogle, James 943.6044 BOG Empress Zita of Austria-Hungary A helping hand : A reflection guide for the divorced, Horstman, James L. -

The Catholic Voyage: African Journal of Consecrated Life Vol

The Catholic Voyage: African Journal of Consecrated Life Vol. 15, 2019. ISSN: 2659-0301 (Online) 1597 6610 (Print) RELIGIOUS LIFE IN THE ORIENTATIONS OF THE CHURCH: THE CHALLENGES OF FORMATION IN NIGERIA Oseni J. Ogunu, OMV1 ABSTRACT Although expressed in different manner, the Consecrated life is often presented, essentially, as a beautiful and precious treasure, a calling and way of life rooted in our baptismal vocation and founded on the Triune God. The desire of those who are called is to follow Jesus Christ more closely by loving and serving God and fellow human persons, according to the spirit and charism of the Founder/Foundress. In order to faithfully achieve this aim, the Institutes of Consecrated life endeavour to form or educate is members. The Church has constantly showed concern and encouraged the formation of consecrated persons. She offers guidelines and directives in response to new questions and emerging difficulties, and changing situations both in the Church and in society. The article presents some orientations of the Church and, then, the challenges that face formation in religious life in an African country (Nigeria) today. Notwithstanding the real challenges, the formation in consecrated life is a call to commitment and witness to Christ in the church and in the world today. Key words: Catholic Church, Consecrated Life, Formation, Nigeria Introduction “Consecrated life is beautiful, it is one of the Church’s most precious treasures, rooted in baptismal vocation. Thus it is beautiful to be its formators, because it is a privilege to take part in the work of the Father who forms the heart of the Son in those whom the Spirit has called. -

The Holy See

The Holy See ADDRESS OF THE HOLY FATHER POPE JOHN PAUL II TO THE MISSIONARIES OF INFINITE LOVE Friday, 4 September 1998 Dear Missionaries of Infinite Love, 1. Welcome to this meeting, which you desired in order to mark the 50th anniversary of the foundation of your secular institute. I extend my cordial greeting to each of you, with a special mention of fraternal affection for Bishop Luigi Bettazzi, who is accompanying you. He rightly wished to join you today as Bishop of the particular Church where the foundation took place, that is, the Diocese of Ivrea. In fact, the Work of Infinite Love originated in that land, made fertile at the beginning of this century by the witness of the Servant of God Mother Luisa Margherita Claret de la Touche, and it was from this work that your family was founded. Having obtained diocesan recognition in 1972, the institute was later approved by me for the whole Church. It is now present, in fact, in various parts of the world. Your basic sentiment in celebrating this anniversary is certainly one of thanksgiving, in which I am very pleased to join. 2. Dear friends, we are living in a year that is entirely dedicated to the Holy Spirit. Well, is the coincidence that you are celebrating the institute’s 50th anniversary in the year dedicated to the Holy Spirit not another special reason for gratitude? It is only because of the Spirit and in the Spirit that we can say: “God is love” (1 Jn 4: 8;16), a statement that constitutes the inexhaustible core, the well-spring of your spirituality. -

Summer, 2015: Volume 7 Number 1 •

The International Journal of African Catholicism, Summer, 2015. Volume 7, Number 1 1 The International Journal of African Catholicism, Summer, 2015. Volume 7, Number 1 Table of Contents The African Family from the Experience of a Catholic Couple in Ethiopia By Abel Muse and Tenagnework Haile………………………………………………...3 Family in the Context of Evangelization: Challenges and Opportunities from Sub- Saharan Africa By Mbiribindi Bahati Dieudonné, SJ………………….….…………...……………14 Notes on the Synodal Document “Pastoral Challenges to the Family in the Context of Evangelization” By Nicholas Hamakalu..…..……………………………………………..…………….36 Small Christian Communities (SCCs) Promote Family and Marriage Ministry in Eastern Africa By Joseph G. Healey, MM…………………………………………………………….49 The Image of the Family in Chimanda Ngozi Adiche’s Purple Hibiscus and its Implications for Families in Today’s Africa Adolphus Ekedimma Amaefule……………………………………………………....157 The Gospel of the Family: From Africa to the World Church Philomena N. Mwaura……………………….………………………………………..182 Family and Marriage in Kenya Today: Pastoral Guidelines for a Process of Discussion and Action. Results of the Consultation in Kenya on the 46 Questions in the Lineamenta (guidelines) on The Vocation and Mission of the Family in the Church and Contemporary World………………………………….……………………………………………...200 2 The International Journal of African Catholicism, Summer, 2015. Volume 7, Number 1 The African Family from the Experience of a Catholic Couple in Ethiopia By Abel Muse and Tenagnework Haile Abstract Africans should preserve the noble family life, traditions and cultures that they inherited from their forefathers. They need to exercise it and live it for themselves rather than imitating the culture and living style of others. Each African country has its unique tradition and culture that some may not perceive as their riches. -

The Holy See

The Holy See LETTER OF JOHN PAUL II TO THE MONTFORT RELIGIOUS FAMILY To the Men and Women Religious of the Montfort Families A classical text of Marian spirituality 1. A work destined to become a classic of Marian spirituality was published 160 years ago. St Louis Marie Grignion de Montfort wrote the Treatise on True Devotion to the Blessed Virgin at the beginning of the 1700s, but the manuscript remained practically unknown for more than a century. When, almost by chance, it was at last discovered in 1842 and published in 1843, the work was an instant success, proving extraordinarily effective in spreading the "true devotion" to the Most Holy Virgin. I myself, in the years of my youth, found reading this book a great help. "There I found the answers to my questions", for at one point I had feared that if my devotion to Mary "became too great, it might end up compromising the supremacy of the worship owed to Christ" (Dono e Mistero, Libreria Editrice Vaticana, 1996; English edition: Gift and Mystery, Paulines Publications Africa, p. 42). Under the wise guidance of St Louis Marie, I realized that if one lives the mystery of Mary in Christ this risk does not exist. In fact, this Saint's Mariological thought "is rooted in the mystery of the Trinity and in the truth of the Incarnation of the Word of God" (ibid.). Since she came into being, and especially in her most difficult moments, the Church has contemplated with special intensity an event of the Passion of Jesus Christ that St John mentions: "Standing by the Cross of Jesus were his mother, and his mother's sister, Mary, the wife of Clopas, and Mary Magdalene. -

The Holy See

The Holy See ADDRESS OF HIS HOLINESS POPE JOHN PAUL II TO THE Episcopal Conference of Zaire DURING ITS "Ad limina Apostolorum" VISIT Monday, 3 March 1997 Dear Brothers in the Episcopate, 1. I am pleased to welcome you to the Vatican during your ad limina visit. Pastors of the Church in Zaire in the Ecclesiastical Provinces of Bukavu, Kisangani and Lubumbashi, through your pilgrimage to the tombs of the Apostles, you have come to renew your commitment to the service of Christ’s mission and of his Church, and to reinforce your bond of communion with the Successor of Peter. You come from a country going through a deep, widespread crisis about which your Episcopal Conference has spoken several times. This crisis is seen in the corruption and insecurity, in the social injustice and ethnic antagonism, in the state of total neglect found in the education and health-care sectors, in hunger and epidemics.... In addition, there is now a war, involving your Dioceses in particular, with all its tragic consequences. What great suffering for Zairians! At this painful time I hope that you will find here the comfort and strength to pursue your episcopal mission with confidence among the people entrusted to you. I warmly thank Bishop Faustin Ngabu, President of the Episcopal Conference of Zaire, for his enlightening words about the life of the Church in your country. They show the hope of your communities despite their trials. I greet the priests, the religious, the catechists and all the faithful of your region with special affection and I encourage them to be, in adversity, true disciples of Christ.