The Theory and Practice of Soviet International Law

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Russian Revolutions: the Impact and Limitations of Western Influence

Dickinson College Dickinson Scholar Faculty and Staff Publications By Year Faculty and Staff Publications 2003 The Russian Revolutions: The Impact and Limitations of Western Influence Karl D. Qualls Dickinson College Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.dickinson.edu/faculty_publications Part of the European History Commons Recommended Citation Qualls, Karl D., "The Russian Revolutions: The Impact and Limitations of Western Influence" (2003). Dickinson College Faculty Publications. Paper 8. https://scholar.dickinson.edu/faculty_publications/8 This article is brought to you for free and open access by Dickinson Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion by an authorized administrator. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Karl D. Qualls The Russian Revolutions: The Impact and Limitations of Western Influence After the collapse of the Soviet Union, historians have again turned their attention to the birth of the first Communist state in hopes of understanding the place of the Soviet period in the longer sweep of Russian history. Was the USSR an aberration from or a consequence of Russian culture? Did the Soviet Union represent a retreat from westernizing trends in Russian history, or was the Bolshevik revolution a product of westernization? These are vexing questions that generate a great deal of debate. Some have argued that in the late nineteenth century Russia was developing a middle class, representative institutions, and an industrial economy that, while although not as advanced as those in Western Europe, were indications of potential movement in the direction of more open government, rule of law, free market capitalism. Only the Bolsheviks, influenced by an ideology imported, paradoxically, from the West, interrupted this path of Russian political and economic westernization. -

Mainstreaming Radical Politics in Sri Lanka: the Case of JVP Post-1977

Mainstreaming Radical Politics in Sri Lanka: The case of JVP post-1977 Nirmal Ranjith Dewasiri Abstract This article provides a critical understanding of dynamics behind the roles of the People’s Liberation Front (JVP) in post-1977 Sri Lankan politics. Having suffered a severe setback in the early 1970s, the JVP transformed itself into a significant force in electoral politics that eventually brought the United People’s Freedom Alliance (UPFA) to power. This article explains the transformation by examining the radical political setting and mapping out the actors and various movements which allowed the JVP to emerge as a dominant player within the hegemonic political mainstream in Sri Lanka. Furthermore, it also highlights the structural changes in JVP politics and its challenges for future consolidation. Introduction The 1977 general election marked a major turning point in the history of post-colonial Sri Lanka. While the landslide victory of the United National Party (UNP) was the most important highlight of the election results, the shocking defeat for the old leftist parties was equally important. Both the victory of the UNP and the defeat of the left were symbolic. The left’s electoral defeat was soon followed by the introduction of new macro-economic policy framework under the UNP’s rule, which replaced protective economic policy framework that was endorsed by the Left.1 Ironically enough, as if to dig its own grave, the same UNP government helped People’s Liberation Front (JVP), which became a formidable threat to the smooth implementation of the new economic policies, to re-enter into the political mainstream by way of freeing its leadership from the prison. -

Jacques Camatte Community and Communism in Russia

Jacques Camatte Community and Communism in Russia Chapter I Chapter II Chapter III Chapter I Publishing Bordiga's texts on Russia and writing an introduction to them was rather repugnant to us. The Russian revolution and its involution are indeed some of the greatest events of our century. Thanks to them, a horde of thinkers, writers, and politicians are not unemployed. Among them is the first gang of speculators which asserts that the USSR is communist, the social relations there having been transformed. However, over there men live like us, alienation persists. Transforming the social relations is therefore insufficient. One must change man. Starting from this discovery, each has 'functioned' enclosed in his specialism and set to work to produce his sociological, ecological, biological, psychological etc. solution. Another gang turns the revolution to its account by proving that capitalism can be humanised and adapted to men by reducing growth and proposing an ethic of abstinence to them, contenting them with intellectual and aesthetic productions, restraining their material and affective needs. It sets computers to work to announce the apocalypse if we do not follow the advice of the enlightened capitalist. Finally there is a superseding gang which declares that there is neither capitalism nor socialism in the USSR, but a kind of mixture of the two, a Russian cocktail ! Here again the different sciences are set in motion to place some new goods on the over-saturated market. That is why throwing Bordiga into this activist whirlpool -

From Proletarian Internationalism to Populist

from proletarian internationalism to populist russocentrism: thinking about ideology in the 1930s as more than just a ‘Great Retreat’ David Brandenberger (Harvard/Yale) • [email protected] The most characteristic aspect of the newly-forming ideology... is the downgrading of socialist elements within it. This doesn’t mean that socialist phraseology has disappeared or is disappearing. Not at all. The majority of all slogans still contain this socialist element, but it no longer carries its previous ideological weight, the socialist element having ceased to play a dynamic role in the new slogans.... Props from the historic past – the people, ethnicity, the motherland, the nation and patriotism – play a large role in the new ideology. –Vera Aleksandrova, 19371 The shift away from revolutionary proletarian internationalism toward russocentrism in interwar Soviet ideology has long been a source of scholarly controversy. Starting with Nicholas Timasheff in 1946, some have linked this phenomenon to nationalist sympathies within the party hierarchy,2 while others have attributed it to eroding prospects for world This article builds upon pieces published in Left History and presented at the Midwest Russian History Workshop during the past year. My eagerness to further test, refine and nuance this reading of Soviet ideological trends during the 1930s stems from the fact that two book projects underway at the present time pivot on the thesis advanced in the pages that follow. I’m very grateful to the participants of the “Imagining Russia” conference for their indulgence. 1 The last line in Russian reads: “Bol’shuiu rol’ v novoi ideologii igraiut rekvizity istoricheskogo proshlogo: narod, narodnost’, rodina, natsiia, patriotizm.” V. -

Killing Hope U.S

Killing Hope U.S. Military and CIA Interventions Since World War II – Part I William Blum Zed Books London Killing Hope was first published outside of North America by Zed Books Ltd, 7 Cynthia Street, London NI 9JF, UK in 2003. Second impression, 2004 Printed by Gopsons Papers Limited, Noida, India w w w.zedbooks .demon .co .uk Published in South Africa by Spearhead, a division of New Africa Books, PO Box 23408, Claremont 7735 This is a wholly revised, extended and updated edition of a book originally published under the title The CIA: A Forgotten History (Zed Books, 1986) Copyright © William Blum 2003 The right of William Blum to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. Cover design by Andrew Corbett ISBN 1 84277 368 2 hb ISBN 1 84277 369 0 pb Spearhead ISBN 0 86486 560 0 pb 2 Contents PART I Introduction 6 1. China 1945 to 1960s: Was Mao Tse-tung just paranoid? 20 2. Italy 1947-1948: Free elections, Hollywood style 27 3. Greece 1947 to early 1950s: From cradle of democracy to client state 33 4. The Philippines 1940s and 1950s: America's oldest colony 38 5. Korea 1945-1953: Was it all that it appeared to be? 44 6. Albania 1949-1953: The proper English spy 54 7. Eastern Europe 1948-1956: Operation Splinter Factor 56 8. Germany 1950s: Everything from juvenile delinquency to terrorism 60 9. Iran 1953: Making it safe for the King of Kings 63 10. -

The Dangers of Forgetting the Legacy of Communism Communism As Antidevelopment

APRIL 2018 COVER PHOTO PAULA BRONSTEIN/GETTY IMAGES The Dangers of 1616 Rhode Island Avenue NW Washington, DC 20036 202 887 0200 | www.csis.org Forgetting the Legacy of Communism Communism as Antidevelopment AUTHORS Romina Bandura Brunilda Kosta A Report of the CSIS PROJECT ON PROSPERITY AND DEVELOPMENT and CSIS PROJECT ON MILITARY AND DIPLOMATIC HISTORY Blank APRIL 2018 The Dangers of Forgetting the Legacy of Communism Communism as Antidevelopment AUTHORS Romina Bandura Brunilda Kosta A Report of the CSIS PROJECT ON PROSPERITY AND DEVELOPMENT and CSIS PROJECT ON MILITARY AND DIPLOMATIC HISTORY About CSIS For over 50 years, the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) has worked to develop solutions to the world’s greatest policy challenges. Today, CSIS scholars are providing strategic insights and bipartisan policy solutions to help decisionmakers chart a course toward a better world. CSIS is a nonprofit organization headquartered in Washington, D.C. The Center’s 220 full-time staff and large network of affiliated scholars conduct research and analysis and develop policy initiatives that look into the future and anticipate change. Founded at the height of the Cold War by David M. Abshire and Admiral Arleigh Burke, CSIS was dedicated to finding ways to sustain American prominence and prosperity as a force for good in the world. Since 1962, CSIS has become one of the world’s preeminent international institutions focused on defense and security; regional stability; and transnational challenges ranging from energy and climate to global health and economic integration. Thomas J. Pritzker was named chairman of the CSIS Board of Trustees in November 2015. -

288381679.Pdf

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Loughborough University Institutional Repository This item was submitted to Loughborough University as a PhD thesis by the author and is made available in the Institutional Repository (https://dspace.lboro.ac.uk/) under the following Creative Commons Licence conditions. For the full text of this licence, please go to: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/2.5/ Towards a Libertarian Communism: A Conceptual History of the Intersections between Anarchisms and Marxisms By Saku Pinta Loughborough University Submitted to the Department of Politics, History and International Relations in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) Approximate word count: 102 000 1. CERTIFICATE OF ORIGINALITY This is to certify that I am responsible for the work submitted in this thesis, that the original work is my own except as specified in acknowledgments or in footnotes, and that neither the thesis nor the original work contained therein has been submitted to this or any other institution for a degree. ……………………………………………. ( Signed ) ……………………………………………. ( Date) 2 2. Thesis Access Form Copy No …………...……………………. Location ………………………………………………….……………...… Author …………...………………………………………………………………………………………………..……. Title …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….. Status of access OPEN / RESTRICTED / CONFIDENTIAL Moratorium Period :…………………………………years, ending…………../…………20………………………. Conditions of access approved by (CAPITALS):…………………………………………………………………… Supervisor (Signature)………………………………………………...…………………………………... Department of ……………………………………………………………………...………………………………… Author's Declaration : I agree the following conditions: Open access work shall be made available (in the University and externally) and reproduced as necessary at the discretion of the University Librarian or Head of Department. It may also be digitised by the British Library and made freely available on the Internet to registered users of the EThOS service subject to the EThOS supply agreements. -

Anarchism and Council-Communism on the Russian Revolution

Anarchist Studies 20.2 30/10/2012 21:36 Page 22 View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Abertay Research Portal Anarchist Studies 20.2 © 2012 ISSN 0967 3393 www.lwbooks.co.uk/journals/anarchiststudies/ Anarchism and Council Communism on the Russian Revolution Christos Memos ABSTRACT The Russian Revolution, being part of the revolutionary tradition of the exploited and oppressed, encompasses sufferings, horrors and tragedies, but also unfulfilled promises, hopes and revolutionary inspirations. The subversive heritage includes, among others, the largely neglected radical critiques of the Russian Revolution that preceded analo- gous Trotskyist endeavours. All these forgotten critiques, unrealised potentials and past struggles could act as a constantly renewed point of departure in the fight for human emancipation. This essay examines the two radical currents of anarchism and Council Communism and their critical confrontation with the Russian Revolution and the class character of the Soviet regime. First, it outlines the major anarchist critiques and analyses of the revolution (Kropotkin, Malatesta, Rocker, Goldman, Berkman and Voline). Following this, it explores the critique provided by the Council Communist tradition (Pannekoek, Gorter and Rühle). The essay moves on to provide a critical re-evaluation of both anarchist and councilist appraisals of the Russian Revolution in order to disclose liberating intentions and tendencies that are living possibilities for contemporary radical anti-capitalist struggles all over the world. It also attempts to shed light on the limits, inadequacies and confusions of their approaches, derive lessons for the present social struggles and make explicit the political and theo- retical implications of this anti-critique. -

Forging the Enemy in Soviet Fiction and Press

Forging the Enemy in Soviet Fiction and Press 1945-1982 Raphaelle Auclert Supervisors: Prof. Evgeny Dobrenko and Prof. Craig Brandist University of Sheffield 1 Table of Contents Introduction 4 First Part: The Stalin Era. The Enemy with a Cloak and a Dagger Chapter 1. The Cold War Begins: Historical and Cultural Background 27 1.1. A Fragile Grand Alliance 28 1.2. The Bipolar Brinkmanship: First Round 29 1.3. The Soviet ‘Peace Offensive’ 37 1.4. Postwar ‘Politerature’ and the ‘Manufacture of the Enemy’ 42 Chapter 2. Case Studies: The Enemy Outside: I. Ehrenburg and N. Shpanov 51 Chapter 3. Case Studies: The Enemy Inside the Communist Movement: 89 D. Eriomin and O. Maltsev Second Part: Khrushchev Era. The Ideological Enemy Chapter 4. The Making of the Thaw Enemy on the Cold War Stage 119 4.1. “Peaceful Coexistence” or the Vanishing of the Outside Enemy 119 4.2. Case Study: The Enemy Within: V. Kochetov 126 Chapter 5. Khrushchev’s Apocrypha 130 Chapter 6. The literary ‘Morality Police’ 148 Third Part: Brezhnev Era: Confronting an Invisible Enemy Chapter 7. The Brezhnev Doctrine 157 Chapter 8. Case Study: Enemy at Heart. Y. Bondarev’s The Shore 169 Chapter 9. Case Study: Becoming Your Enemy: Y. Bondarev’s The Choice 181 Conclusion 193 Bibliography 199 2 Forging the Enemy in Soviet Fiction and Press, 1945-1982 Abstract My dissertation offers a new approach to the study of Soviet official prose in the context of Soviet politics and of the Cold War. The Cold War was an ideological contest between two blocs: capitalist and communist. -

KEY INFORMATION RESOURCES September 2017 Library and Research

Council of the European Union General Secretariat KEY INFORMATION RESOURCES September 2017 Library and Research Suggestions for further reading from the holdings of the GSC Libraries and online European Day of Languages 26.09.2017 Due to copyright issues, some online articles are only available on request at the Library MULTILINGUALISM ............................................................................................................................... 1 LANGUAGE SKILLS .............................................................................................................................. 4 TRANSLATION ...................................................................................................................................... 6 EU RELATED POETRY IN DIFFERENT LANGUAGES ............................................................................. 7 LANGUAGE IN RELATION TO IDEOLOGY, RELIGION, AND CULTURE .................................................. 7 Multilingualism Viva il latino : Storie e bellezza di una lingua inutile / Nicola Gardini. Milano : Garzanti, 2017. Monograph available ita 807.1 GARD A che serve il latino? È la domanda che continuamente sentiamo rivolgerci dai molti per i quali la lingua di Cicerone altro non è che un’ingombrante rovina, da eliminare dai programmi scolastici. In questo libro personale e appassionato, Nicola Gardini risponde che il latino è - molto semplicemente lo strumento espressivo che è servito e serve a fare di noi quelli che siamo. Gardini ci trasmette un amore alimentato -

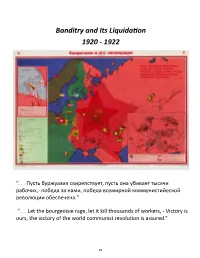

Map 10 Banditry and Its Liquidation // 1920 - 1922 Colored Lithographic Print, 64 X 102 Cm

Banditry and Its Liquidation 1920 - 1922 “. Пусть буржуазия свирепствует, пусть она убивает тысячи рабочих,- победа за нами, победа всемирной коммунистийеской революции обеспечена.” “. Let the bourgeoisie rage, let it kill thousands of workers, - Victory is ours, the victory of the world communist revolution is assured.” 62 Map 10 Banditry and Its Liquidation // 1920 - 1922 Colored Lithographic print, 64 x 102 cm. Compilers: A. N. de-Lazari and N. N. Lesevitskii Artist: S. R. Zelikhman Historical Background and Thematic Design The Russian Civil War did not necessarily end with the defeat of the Whites. Its final stage involved various independent bands of partisans and rebels that took advantage of the chaos enveloping the country and contin- ued to operate in rural areas of Ukraine, Tambov Province, the lower Volga, and western Siberia, where Bol- shevik authority was more or less tenuous. Their leaders were by and large experienced military men who stoked peasant hatred for centralized authority, whether it was German occupation forces, Poles, Moscow Bol- sheviks, or Jews. They squared off against the growing power of the communists, which is illustrated as series of five red stars extending over all four sectors. The red circle identifies Moscow as the seat of Soviet power, while the five red stars, enlarging in size but diminishing in color intensity as they move further from Moscow, represent the increasing strength of Communism in Russia during the years 1920-22. The stars also serve as symbolic shields, apparently deterring attacking forces that emanate from Poland, Ukraine, and the Volga region. The red flag with the gold emblem of the hammer-and-sickle in the upper hoist quarter, and the letters Р. -

The Adaptability of the FARC and ELN and the Prediction of Their Future Actions

The Adaptability of the FARC and ELN and the Prediction of their Future Actions By Drew Lasater INTL 699 D001 Win Advisor Dr. Jonathan S. Lockwood 1 Introduction Colombia is Latin America’s oldest democracy yet the nation has faced continual violence and a guerrilla war that has made the nation weak and fragmented. This violent foundation of the Colombian state made it open to a new wave of political ideologies in the 20th century. The movement of Marxism-Leninism spread across Latin America, especially among the intellectuals, peasants, and priests in Colombia. The purpose of this research is to provide an analysis of the two main guerrilla factions in the country – the FARC and the ELN – and predict the future of these groups. Studying the history of these organizations and their adaptability within the Colombian context provides insight into the emergence of guerrilla warfare and the problems for the state. Colombia has been in social and political turmoil since independence. Like most Latin American countries, Colombia developed a political system based on an oligarchy between the political and landed elite with the working poor and peasantry at the bottom. As Colombia began interacting with international markets and businesses it produced economic growth and prosperity for the elite while leaving the impoverished and marginalized populace open to the spread of revolutionary political ideologies. The FARC and ELN emerged as the masses at the bottom of the social strata were alienated by the ruling elite and their political system. While Colombia is a popularly elected democracy there was little participation or reward for those outside of the two party Liberals and Conservatives.