Organic Livestock Production

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Sustainable Approach for Improving Soil Properties and Reducing N2O Emissions Is Possible Through Initial and Repeated Biochar Application

agronomy Article A Sustainable Approach for Improving Soil Properties and Reducing N2O Emissions Is Possible through Initial and Repeated Biochar Application Ján Horák 1,* , Tatijana Kotuš 1, Lucia Toková 1, Elena Aydın 1 , Dušan Igaz 1 and Vladimír Šimanský 2 1 Department of Biometeorology and Hydrology, Faculty of Horticulture and Landscape Engineering, Slovak University of Agriculture, 949 76 Nitra, Slovakia; [email protected] (T.K.); [email protected] (L.T.); [email protected] (E.A.); [email protected] (D.I.) 2 Department of Soil Science, Faculty of Agrobiology and Food Resources, Slovak University of Agriculture, 949 76 Nitra, Slovakia; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Recent findings of changing climate, water scarcity, soil degradation, and greenhouse gas emissions have brought major challenges to sustainable agriculture worldwide. Biochar application to soil proves to be a suitable solution to these problems. Although the literature presents the pros and cons of biochar application, very little information is available on the impact of repeated application. In this study, we evaluate and discuss the effects of initial and reapplied biochar (both in rates of 0, 10, and 20 t ha−1) combined with N fertilization (at doses of 0, 40, and 80 kg ha−1) on soil properties and N O emission from Haplic Luvisol in the temperate climate zone (Slovakia). Results showed that 2 biochar generally improved the soil properties such as soil pH(KCl) (p ≤ 0.05; from acidic towards Citation: Horák, J.; Kotuš, T.; Toková, moderately acidic), soil organic carbon (p ≤ 0.05; an increase from 4% to over 100%), soil water L.; Aydın, E.; Igaz, D.; Šimanský, V. -

Bacteria in Agrobiology: Stress Management

Bacteria in Agrobiology: Stress Management Bearbeitet von Dinesh K. Maheshwari 1. Auflage 2012. Buch. XII, 333 S. Hardcover ISBN 978 3 642 23464 4 Format (B x L): 15,5 x 23,5 cm Gewicht: 684 g Weitere Fachgebiete > Chemie, Biowissenschaften, Agrarwissenschaften > Entwicklungsbiologie > Bakteriologie (nichtmedizinisch) Zu Inhaltsverzeichnis schnell und portofrei erhältlich bei Die Online-Fachbuchhandlung beck-shop.de ist spezialisiert auf Fachbücher, insbesondere Recht, Steuern und Wirtschaft. Im Sortiment finden Sie alle Medien (Bücher, Zeitschriften, CDs, eBooks, etc.) aller Verlage. Ergänzt wird das Programm durch Services wie Neuerscheinungsdienst oder Zusammenstellungen von Büchern zu Sonderpreisen. Der Shop führt mehr als 8 Millionen Produkte. Chapter 2 The Management of Soil Quality and Plant Productivity in Stressed Environment with Rhizobacteria Dilfuza Egamberdieva 2.1 Introduction The urgency of feeding the world’s growing population while combating soil pollution, salinization, and desertification has given plant and soil productivity research vital importance. Under such circumstances, it requires suitable biotech- nology not only to improve crop productivity but also to improve soil health through interactions of plant roots and soil microorganisms (Lugtenberg et al. 2002). Interest in bacterial fertilizers has increased, as it would substantially reduce the use of chemical fertilizers and pesticides which often contribute to the pollution of soil–water ecosystems. Presently, about 20 biocontrol products based on Pseu- domonas, Bacillus, Streptomyces, and Agrobacterium strains have been commercialized, but there still is a need to improve the efficacy of these biocontrol products (Copping 2004; Chebotar et al. 2000; Lugtenberg and Kamilova 2004). Soil salinity disturbs the plant–microbe interaction, which is a critical ecological factor to help further plant growth in degraded ecosystems (Paul and Nair 2008). -

The Effect of Different Doses of N Fertilization on the Parameters of Soil Organic Matter and Soil Sorption Complex

Journal of Ecological Engineering Volume 18, Issue 3, May 2017, pages 104–111 DOI: 10.12911/22998993/69366 Research Article THE EFFECT OF DIFFERENT DOSES OF N FERTILIZATION ON THE PARAMETERS OF SOIL ORGANIC MATTER AND SOIL SORPTION COMPLEX Vladimír Šimanský1, Peter Kováčik2, Jerzy Jonczak3 1 Department of Soil Science, Faculty of Agrobiology and Food Resources, Slovak University of Agriculture, Tr. A. Hlinku 2, 949 76 Nitra, Slovakia, e-mail: [email protected] 2 Department of Agrochemistry and Plant Nutrition, Faculty of Agrobiology and Food Resources, Slovak University of Agriculture, Tr. A. Hlinku 2, 949 76 Nitra, Slovakia 3 Department of Soil Environment Sciences, Warsaw University of Life Sciences – SGGW, Poland Received: 2017.06.03 ABSTRACT Accepted: 2017.04.05 Mineral N fertilizer application may have an effect on soil organic matter and other Published: 2017.05.02 soil parameters. Therefore, we studied the effects of different doses of N fertilization on soil organic matter and chemical properties of Haplic Luvisol in the locality of Dolná Malanta (Slovakia) during 2014–2016. Soil samples were collected from the plots exposed to the following treatments: 1. N0 – no N fertilization as control dur- ing 2014–2016, 2. N40 – N fertilizer at the rate of 40 kg N ha–1 in 2014 and 2016, 3. N80 – N fertilizer at the rate of 80 kg N ha–1 in 2014 and 2016, 4. N160 – N fertilizer at the rate of 160 kg N ha–1 in 2015, and 5. N240 – N fertilizer at the rate of 240 kg N ha–1 in 2015. -

Revisiting the Standard Soil Test: the Potential of Macro- and Microbiological Measures to Improve Agricultural Health and Productivity

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Theses and Dissertations Fall 2019 Revisiting the Standard Soil Test: The Potential of Macro- and Microbiological Measures to Improve Agricultural Health and Productivity Gabriel Jacob Kenne Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd Part of the Environmental Health Commons Recommended Citation Kenne, G. J.(2019). Revisiting the Standard Soil Test: The Potential of Macro- and Microbiological Measures to Improve Agricultural Health and Productivity. (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd/5547 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you by Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. REVISITING THE STANDARD SOIL TEST: THE POTENTIAL OF MACRO- AND MICROBIOLOGICAL MEASURES TO IMPROVE AGRICULTURAL HEALTH AND PRODUCTIVITY by Gabriel Jacob Kenne Bachelor of Science University of Nebraska at Omaha, 2008 Master of Public Health Kansas State University, 2013 Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Environmental Health Sciences The Norman J. Arnold School of Public Health University of South Carolina 2019 Accepted by: R. Sean Norman, Major Professor Anindya Chanda, Committee Member Robin “Buz” Kloot, Committee Member Geoff Zehnder, Committee Member Cheryl L. Addy, Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School © Copyright Gabriel Jacob Kenne, 2019 All Rights Reserved ii ABSTRACT The agricultural ecosystem has become the largest non-ice-covered terrestrial ecosystem on the planet and has significant direct and indirect impacts on the global health of both the environment and humanity. -

Table S1. Microbiological Tools in Agriculture, Available on the Markets in 2021 with Published Field Test Reports

Table S1. Microbiological tools in agriculture, available on the markets in 2021 with published field test reports. Name Species Organism type Application Target Reference Ladurner, E., Benuzzi, M., Fiorentini, F., & Lucchi, A. (2012). Efficacy of Amylo-X®, a new fungicide/bactericide based on Controls gray mold (Botrytis cinerea), Bacillus amyloliquefaciens strain Amylo-X Bacillus amyloliquefaciens PGPR biocontrol Fire blight (Erwinia amylovora) in D747 for the control of microbial grapes, apple,pPear, strawberry plant pathogens. Giornate Fitopatologiche 2012, Milano Marittima (RA), 13-16 marzo 2012, 229-236. Woo, S. L., Ruocco, M., Vinale, F., Nigro, M., Marra, R., Lombardi, N., ... Control of damping-off, seed and root, Trichoderma viride, & Lorito, M. (2014). Trichoderma- ANOKA mix biocontrol nematode wilt in vegetable, tuber, Pseudomonas fluorescens based products and their widespread cotton, chilli crops use in agriculture. The Open Mycology Journal, 8(1). Shishkoff, N., & McGrath, M. T. (2002). AQ10 biofungicide combined Controls powdery mildews in grapes, AQ10 with chemical fungicides or AddQ Ampelomyces quisqalis M-10 soil fungi biocontrol apples, aubergine, tomatoes, strawberry, Biofungicide spray adjuvant for control of cucurbit cucumber powdery mildew in detached leaf culture. Plant Disease, 86(8), 915-918. Alafeea, R. A. A., Alamery, A. A., & Kalaf, I. T. (2019). Effect of bio Improves nitrogen availability in maize fertilizers on increasing the efficiency Azotovit Azotobacter chroococcum PGPR biofertilizer and broccoli of using chemical fertilizers on the yield component of maize (Zea mays L.). Plant Archives, 19(2), 303-306. Katai, J., Sandor, Z., & Tallai, M. (2008). The effect of an artificial and a Azospirillum brasilense, bacterium fertilizer on some soil Azotobacter vinelandii, Bacillus Improves nutrient acquisition on BactoFil A10 mix biofertilizer characteristics and on the biomass of megaterium, B. -

Using Foliar Applications of Magnesium and Potassium to Improve Yields and Some Qualitative Parameters of Vine Grapes (Vitis Vinifera L.)

Plant Soil Environ. Vol. 61, 2015, No. 10: 451–457 doi: 10.17221/437/2015-PSE Using foliar applications of magnesium and potassium to improve yields and some qualitative parameters of vine grapes (Vitis vinifera L.) T. Zlámalová1, J. Elbl2, M. Baroň3, H. Bělíková4, L. Lampíř5, J. Hlušek6, T. Lošák6 1Faculty of Agronomy, Mendel University in Brno, Brno, Czech Republic 2Faculty of Forestry and Wood Technology, Mendel University in Brno, Brno, Czech Republic 3Faculty of Horticulture, Mendel University in Brno, Lednice, Czech Republic 4Department of Technologies, Research and Breeding Institute of Pomology Holovousy Ltd., Hořice, Czech Republic 5Faculty of Agrobiology, Food and Natural Resources, Czech University of Life Sciences Prague, Prague, Czech Republic 6Faculty of Regional Development and International Studies, Mendel University in Brno, Brno, Czech Republic ABSTRACT In a three-year field experiment (2011–2013) we assessed the effect of magnesium (MgSO4) and potassium (K2SO4) applied as foliar applications both separately (3.86 kg Mg/ha or 12.44 kg K/ha) and in combination (1.93 kg Mg/ha + 6.22 kg K/ha) on yields of grapes of cv. Zweigelt and some qualitative parameters of the grapes. The applications were repeated 4 times in stages BBCH 15–19; 55; 75 and 83. The experiment was carried out on soil well supplied with Mg and K in the subsoil layer. In terms of average 3-year results the grape yields were by 11.2% (MgSO4), 13.9% (K2SO4) and 6.6% (MgSO4 + K2SO4) significantly higher than the untreated control. The sugar content of grapes (sum of glucose and fructose) was lower (mostly insignificantly) by 0.5–4.3% in all the fertilized treatments than in the untreated control. -

Organic Variety Testing

Organic Variety Testing Qualitative content analysis approach to assess organic variety testing, case study of Germany Master’s Thesis by Kaja Gutzen Organic Agriculture and Food Systems Agrobiology Double Degree at Aarhus University 14th of June 2019 Organic Variety Testing Qualitative content analysis approach to assess organic variety testing, case study of Germany Master’s Thesis [30 ECTS] by Kaja Gutzen [201801238] Organic Agriculture and Food Systems Agrobiology Double Degree Aarhus University 14th of June 2019 SUPERVISORS and CENSORS JOHANNES RAVN JØRGENSEN TOVE MARIEGAARD PEDERSEN Associate Professor Advisor in Crop Production Department of Agroecology, Crop Health Organic Innovation Aarhus University SEGES Landbrug & Fødevarer F.m.b.A. LARS BONDE ERIKSEN SABINE ZIKELI Advisor in Grain Production Dr. agr. Plant Innovation Centre for Organic Farming SEGES Landbrug & Fødevarer F.m.b.A. University of Hohenheim COPYRIGHT STATEMENT I, Kaja Gutzen Born on 13/11/1991 Matriculation number: 201801238 hereby declare on my honor that the master’s thesis attached to this declaration has been independently prepared, solely with the support of the listed literature references, and that no information has been presented that has not been officially acknowledged. All parts of this work that were taken verbatim or in spirit from publications or outside communications are individually marked as such. Supervisors and censors: Johannes Ravn Jørgensen, Lars Bonde Eriksen, Tove Mariegaard Pedersen, and Sabine Zikeli Thesis topic: Organic Variety Testing I declare herewith, that I have transferred the final digital, not write-protected text document to my mentoring supervisors and censors and that the content and wording is entirely my own work. -

Soil Fertility Management in Apple Orchard with Microbial Biofertilizers

E3S Web of Conferences 222, 03020 (2020) https://doi.org/10.1051/e3sconf/202022203020 DAIC 2020 Soil fertility management in apple orchard with microbial biofertilizers Andrei Kuzin1,3,,⃰ Alexei Solovchenko1,2, Ludmila Stepantsova3, и Grigory Pugachev1 1 I.V. Michurin Federal Scientific Centre, Michurins str., 30, Michurinsk, 393774, Russia 3Lomonosov Moscow State University, Leninskie Gory, 1, Москва, 119991, Russia 3 Michurinsk State Agrarian University, Internarsionalnaya str., 101, Michurinsk, 393760, Russia Abstract. Intensification of horticulture in Russia involves planting of new high-density orchards with drip irrigation and fertigation as well as intensification of the exploitation of traditional orchards. This approach involves an increase in mineral fertilizer application imposing the risk of soil fertility loss. For several reasons, the use of traditional organic fertilizers like manure in orchards is currently marginal. Although bacteria- based biofertilizers cannot substitute mineral fertilizers completely, they can significantly reduce the need for mineral fertilizer application. The effect of microbial biofertilizers of the brands "Azotovit" (Azotobacter chroococcum), "Phosphatovit" (Bacillus mucilaginosus), as well as a mixture of bacteria and the fungus, "Organic" (Azotobacter chroococcum, Bacillus subtilis, Bacillus megaterium, Trichoderma harzian) was studied in two field experiments. In the experiment #1, the preparations "Azotovit" and "Phosphatovit" were delivered through a drip irrigation system in various combinations with mineral fertilizers. In experiment #2, the preparation "Organic" was also applied to the soil with irrigation water, also in combination with the mineral fertilizer. When solely applied, none of the studied preparations changed significantly the soil nutrient content and yield as compared with the variant fertilized by the mineral fertilizer at the maximum studied application rate. -

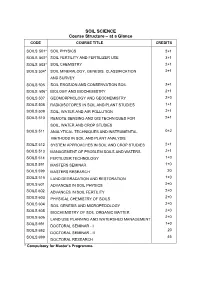

SOIL SCIENCE Course Structure – at a Glance

SOIL SCIENCE Course Structure – at a Glance CODE COURSE TITLE CREDITS SOILS 501* SOIL PHYSICS 2+1 SOILS 502* SOIL FERTILITY AND FERTILIZER USE 3+1 SOILS 503* SOIL CHEMISTRY 2+1 SOILS 504* SOIL MINERALOGY, GENESIS, CLASSIFICATION 2+1 AND SURVEY SOILS 505 SOIL EROSION AND CONSERVATION SOIL 2+1 SOILS 506* BIOLOGY AND BIOCHEMISTRY 2+1 SOILS 507 GEOMORPHOLOGY AND GEOCHEMISTRY 2+0 SOILS 508 RADIOISOTOPES IN SOIL AND PLANT STUDIES 1+1 SOILS 509 SOIL, WATER AND AIR POLLUTION 2+1 SOILS 510 REMOTE SENSING AND GIS TECHNIQUES FOR 2+1 SOIL, WATER AND CROP STUDIES SOILS 511 ANALYTICAL TECHNIQUES AND INSTRUMENTAL 0+2 METHODS IN SOIL AND PLANT ANALYSIS SOILS 512 SYSTEM APPROACHES IN SOIL AND CROP STUDIES 2+1 SOILS 513 MANAGEMENT OF PROBLEM SOILS AND WATERS 2+1 SOILS 514 FERTILIZER TECHNOLOGY 1+0 SOILS 591 MASTERS SEMINAR 1+0 SOILS 599 MASTERS RESEARCH 20 SOILS 515 LAND DEGRADATION AND RESTORATION 1+0 SOILS 601 ADVANCES IN SOIL PHYSICS 2+0 SOILS 602 2+0 ADVANCES IN SOIL FERTILITY SOILS 603 2+0 PHYSICAL CHEMISTRY OF SOILS SOILS 604 2+0 SOIL GENESIS AND MICROPEDOLOGY SOILS 605 2+0 BIOCHEMISTRY OF SOIL ORGANIC MATTER SOILS 606 2+0 LAND USE PLANNING AND WATERSHED MANAGEMENT SOILS 691 1+0 DOCTORAL SEMINAR - I SOILS 692 20 DOCTORAL SEMINAR - II SOILS 699 45 DOCTORAL RESEARCH * Compulsory for Master’s Programme. Minor Departments 9 Agronomy Plant Physiology Microbiology Supporting Departments 5 Statistics & Mathematics Biochemistry Microbiology Environmental Science & Technology Horticulture Non credit compulsory courses CODE COURSE TITLE CREDITS PGS 501 LIBRARY AND INFORMATION SERVICES 0+1 PGS 502 TECHNICAL WRITING AND COMMUNICATION SKILLS 0+1 PGS 503 INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY AND ITS 1+0 (e-course) MANAGEMENT IN AGRICULTURE PGS 504 BASIC CONCEPTS IN LABORATORY TECHNIQUES 0+1 PGS 505 AGRICULTURAL RESEARCH, RESEARCH (e-course) ETHICS AND RURAL DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMMES 1+0 PGS 506 DISASTER MANAGEMENT 1+0 (e-course) SOILS 501 SOIL PHYSICS 2+1 Objective To impart basic knowledge about soil physical properties and processes in relation to plant growth. -

Integrated Use of Compost and Nitrogen Fertilizer and Its Effects on Yield and Yield Components of Wheat

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.10.07.329524; this version posted October 7, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY 4.0 International license. 1 Integrated Use of Compost and Nitrogen Fertilizer and its Effects on 2 Yield and Yield Components of Wheat: A Pot Experiment 3 4 Bayu Dume1*, Gezahegn Berecha2, Melkamu Mamuye3, Obsu Hirko4, Amsalu Nebiyu2, 5 Abebe Nigussie4, Aleš Hanč1, Pavel Švehla1 6 1Department of Agro-environmental Chemistry and Plant Nutrition, Faculty of 7 Agrobiology, Food and Natural Resources, Czech University of Life Sciences Prague, 8 Czech Republic. 9 2Department of Horticulture and Plant Science, College of Agriculture and Veterinary 10 Medicine, Jimma University, Jimma, Ethiopia. 11 3College of Agriculture and Veterinary Medicine-CASCAPE (joint Ethio-Netherland 12 project) Jimma University, Jimma, Ethiopia. 13 4Departments of Natural Resource Management, College of Agriculture and Veterinary 14 Medicine, Jimma University,Jimma, Ethiopia.*[email protected] 15 Abstract 16 There is a research gap and no investigation on combined effects of compost produced 17 from coffee husk and inorganic nitrogen fertilizer (Urea). The objective of this study 18 was to evaluate the yield and yield components of wheat (Triticumaestivum L.) under 19 integrated application of compost and nitrogen fertilizer (Urea). A pot experiment in 1 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.10.07.329524; this version posted October 7, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. -

Plant-Growth-Promoting Bacteria Can Impact Zinc Uptake in Zea Mays: an Examination of the Mechanisms of Action Using Functional Mutants of Azospirillum Brasilense

microorganisms Article Plant-Growth-Promoting Bacteria Can Impact Zinc Uptake in Zea mays: An Examination of the Mechanisms of Action Using Functional Mutants of Azospirillum brasilense Alexandra Bauer Housh 1,2,3 , Mary Benoit 4, Stacy L. Wilder 1, Stephanie Scott 1,5 , Garren Powell 1,5, Michael J. Schueller 1,2 and Richard A. Ferrieri 1,2,3,4,* 1 Missouri Research Reactor Center, University of Missouri, Columbia, MO 65211, USA; [email protected] (A.B.H.); [email protected] (S.L.W.); [email protected] (S.S.); [email protected] (G.P.); [email protected] (M.J.S.) 2 Chemistry Department, University of Missouri, Columbia, MO 652101, USA 3 Interdisciplinary Plant Group, University of Missouri, Columbia, MO 65211, USA 4 Division of Plant Sciences, University of Missouri, Columbia, MO 65211, USA; [email protected] 5 Department of Biochemistry, University of Missouri, Columbia, MO 65211, USA * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-573-882-5211 Abstract: Among the PGPB, the genus Azospirillum—with an emphasis on A. brasilense—is likely the most studied microorganism for mitigation of plant stress. Here, we report the investigation of Citation: Housh, A.B.; Benoit, M.; functional mutants HM053, ipdC and FP10 of A. brasilense to understand how the biological functions Wilder, S.L.; Scott, S.; Powell, G.; of these microorganisms can affect host Zn uptake. HM053 is a Nif + constitutively expressed strain Schueller, M.J.; Ferrieri, R.A. - that hyper-fixes N2 and produces high levels of the plant’s relevant hormone auxin. FP10 is a Nif Plant-Growth-Promoting Bacteria strain deficient in N2-fixation. -

Weed Vegetation in Conventional and Organic Farming in West Bohemia (Czech Republic)

Original Paper Plant, Soil and Environment, 67, 2021 (7): 376–382 https://doi.org/10.17221/6/2021-PSE Weed vegetation in conventional and organic farming in West Bohemia (Czech Republic) Luděk Tyšer, Michaela Kolářová*, Ondřej Tulačka, Pavel Hamouz Department of Agroecology and Crop Production, Faculty of Agrobiology, Food and Natural Resources, Czech University of Life Sciences Prague, Prague, Czech Republic *Corresponding author: [email protected] Citation: Tyšer L., Kolářová M., Tulačka O., Hamouz P. (2021): Weed vegetation in conventional and organic farming in West Bohemia (Czech Republic). Plant Soil Environ., 67: 376–382. Abstract: The paper presents species richness and composition of arable weed vegetation in the region of West Bohemia (Czech Republic) in different types of farming (conventional and organic) and grown crops (winter and spring cereals, wide-row crops). During the field survey in the years 2007 to 2017, 105 phytocoenological relevés were recorded. The average species richness in one relevé was significantly higher in organic farming, as well as total weed cover. The lowest species richness was found in wide-row crops. Recently widespread species belonged to the most frequent species in our study. Based on multivariate statistics, the effects of variables on the occurrence of weed species were found as statistically significant. Most of the variability in data was explained by crop, following by type of farming. Weed species of Fabaceae Lindl. family (especially Vicia L.) and many perennial species positively correlated with the organic type of farming. Endangered species were found mainly in organic farming and cereals. Less intensive cultivation with a higher weed cover is beneficial for the promotion of biodiversity.