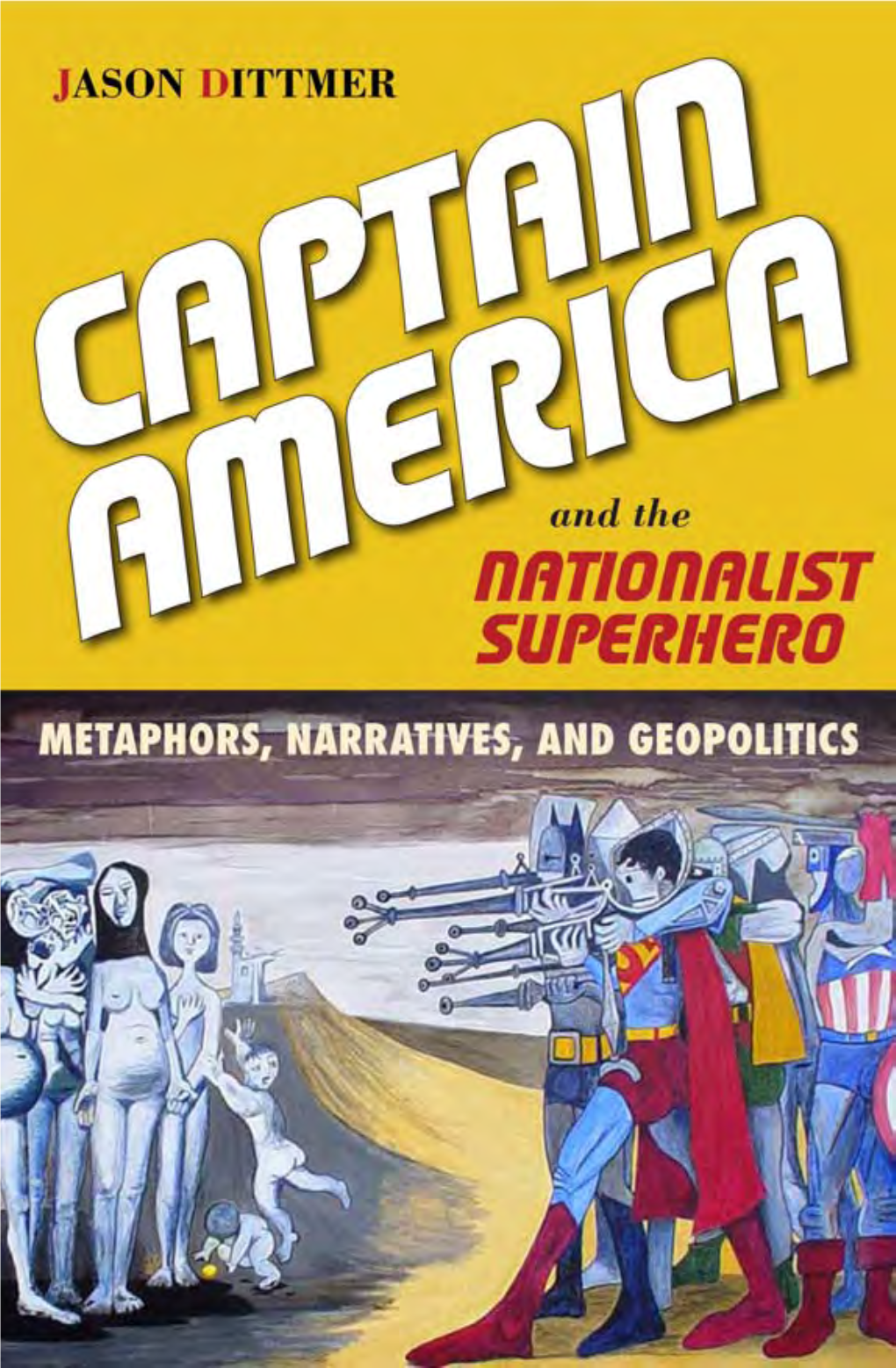

Captain America and the Nationalist Superhero: Metaphors

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Crossing Over: from Black Rhythm Blues to White Rock 'N' Roll

PART2 RHYTHM& BUSINESS:THE POLITICAL ECONOMY OF BLACKMUSIC Crossing Over: From Black Rhythm Blues . Publishers (ASCAP), a “performance rights” organization that recovers royalty pay- to WhiteRock ‘n’ Roll ments for the performance of copyrighted music. Until 1939,ASCAP was a closed BY REEBEEGAROFALO society with a virtual monopoly on all copyrighted music. As proprietor of the com- positions of its members, ASCAP could regulate the use of any selection in its cata- logue. The organization exercised considerable power in the shaping of public taste. Membership in the society was generally skewed toward writers of show tunes and The history of popular music in this country-at least, in the twentieth century-can semi-serious works such as Richard Rodgers and Lorenz Hart, Cole Porter, George be described in terms of a pattern of black innovation and white popularization, Gershwin, Irving Berlin, and George M. Cohan. Of the society’s 170 charter mem- which 1 have referred to elsewhere as “black roots, white fruits.’” The pattern is built bers, six were black: Harry Burleigh, Will Marion Cook, J. Rosamond and James not only on the wellspring of creativity that black artists bring to popular music but Weldon Johnson, Cecil Mack, and Will Tyers.’ While other “literate” black writers also on the systematic exclusion of black personnel from positions of power within and composers (W. C. Handy, Duke Ellington) would be able to gain entrance to the industry and on the artificial separation of black and white audiences. Because of ASCAP, the vast majority of “untutored” black artists were routinely excluded from industry and audience racism, black music has been relegated to a separate and the society and thereby systematically denied the full benefits of copyright protection. -

Title "Stand by Your Man/There Ain't No Future In

TITLE "STAND BY YOUR MAN/THERE AIN'T NO FUTURE IN THIS" THREE DECADES OF ROMANCE IN COUNTRY MUSIC by S. DIANE WILLIAMS Presented to the American Culture Faculty at the University of Michigan-Flint in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Liberal Studies in American Culture Date 98 8AUGUST 15 988AUGUST Firs t Reader Second Reader "STAND BY YOUR MAN/THERE AIN'T NO FUTURE IN THIS" THREE DECADES OF ROMANCE IN COUNTRY MUSIC S. DIANE WILLIAMS AUGUST 15, 19SB TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface Introduction - "You Never Called Me By My Name" Page 1 Chapter 1 — "Would Jesus Wear A Rolen" Page 13 Chapter 2 - "You Ain’t Woman Enough To Take My Man./ Stand By Your Man"; Lorrtta Lynn and Tammy Wynette Page 38 Chapter 3 - "Think About Love/Happy Birthday Dear Heartache"; Dolly Parton and Barbara Mandrell Page 53 Chapter 4 - "Do Me With Love/Love Will Find Its Way To You"; Janie Frickie and Reba McEntire F'aqe 70 Chapter 5 - "Hello, Dari in"; Conpempory Male Vocalists Page 90 Conclusion - "If 017 Hank Could Only See Us Now" Page 117 Appendix A - Comparison Of Billboard Chart F'osi t i ons Appendix B - Country Music Industry Awards Appendix C - Index of Songs Works Consulted PREFACE I grew up just outside of Flint, Michigan, not a place generally considered the huh of country music activity. One of the many misconception about country music is that its audience is strictly southern and rural; my northern urban working class family listened exclusively to country music. As a teenager I was was more interested in Motown than Nashville, but by the time I reached my early thirties I had became a serious country music fan. -

Uncanny Xmen Box

Official Advanced Game Adventure CAMPAIGN BOOK TABLE OF CONTENTS What Are Mutants? ....... .................... ...2 Creating Mutant Groups . ..... ................ ..46 Why Are Mutants? .............................2 The Crime-Fighting Group . ... ............. .. .46 Where Are Mutants? . ........ ........ .........3 The Tr aining Group . ..........................47 Mutant Histories . ................... ... ... ..... .4 The Government Group ............. ....... .48 The X-Men ..... ... ... ............ .... ... 4 Evil Mutants ........................... ......50 X-Factor . .......... ........ .............. 8 The Legendary Group ... ........... ..... ... 50 The New Mutants ..... ........... ... .........10 The Protective Group .......... ................51 Fallen Angels ................ ......... ... ..12 Non-Mutant Groups ... ... ... ............. ..51 X-Terminators . ... .... ............ .........12 Undercover Groups . .... ............... .......51 Excalibur ...... ..............................12 The False Oppressors ........... .......... 51 Morlocks ............... ...... ......... .....12 The Competition . ............... .............51 Original Brotherhood of Evil Mutants ..... .........13 Freedom Fighters & Te rrorists . ......... .......52 The Savage Land Mutates ........ ............ ..13 The Mutant Campaign ... ........ .... ... .........53 Mutant Force & The Resistants ... ......... ......14 The Mutant Index ...... .... ....... .... 53 The Second Brotherhood of Evil Mutants & Freedom Bring on the Bad Guys ... ....... -

The Archives of Let's Talk Dusty! - W…

2010-07-27 The Archives of Let's Talk Dusty! - W… The Archives of Let's Talk Dusty! Home | Profile | Active Topics | Active Polls | Members | Search | FAQ Username: Password: Login Save Password Forgot your Password? All Forums Let's Talk Dusty! The Forum Forum Locked You Set My Dreams To Music Printer Friendly Why did 'Dusty in Memphis' fail to sell? Author Topic memphisinlondon Posted - 08/07/2008 : 20:55:50 Where am I going? Can anyone here give any explanation for why the album failed? I don't believe her previous album 'Dusty Definitely' sold that well either. Had Dusty simply bec ome irrelevant for some reason? Maybe bec ause record buyers didn't understand what she was doing? Maybe young Americans didn't know who she was (the title assumes they did)? Maybe because she broke her mould and left many of her UK fans wondering what was going on, that she'd abandoned them somehow? United Kingdom Was Dusty just out of style or mainly admired as a superstar cabaret 3565 Posts artist (so the 'Memphis' album might be quite puzzling)? Maybe the album wasn't promoted properly. It's hard to work it out from 2008. What's your take? If anybody here was there in 1969 it would be great to hear from you. Memphis Ever since we met... mssdusty Posted - 08/07/2008 : 21:16:07 I’ve got a good thing WELL I GOT MY 8 TRACK TAPE OF DIM ........PLAYED IT ALL THE TIME. I DONT UNDERST AND IT T OO. MARY THE LOOK OF LOVE IS IN YOUR EYES! USA Watch my video with Dusty on YouTube! 5821 Posts Edited by - mssdusty on 08/07/2008 21:16:34 Mark Posted - 08/07/2008 : 21:34:08 I’ve got a good thing I recall reading that after the Single success of SOAPM, the gap between this and the release of DIM was too long.... -

Marvel-Phile

by Steven E. Schend and Dale A. Donovan Lesser Lights II: Long-lost heroes This past summer has seen the reemer- 3-D MAN gence of some Marvel characters who Gestalt being havent been seen in action since the early 1980s. Of course, Im speaking of Adam POWERS: Warlock and Thanos, the major players in Alter ego: Hal Chandler owns a pair of the cosmic epic Infinity Gauntlet mini- special glasses that have identical red and series. Its great to see these old characters green images of a human figure on each back in their four-color glory, and Im sure lens. When Hal dons the glasses and focus- there are some great plans with these es on merging the two figures, he triggers characters forthcoming. a dimensional transfer that places him in a Nostalgia, the lowly terror of nigh- trancelike state. His mind and the two forgotten days, is alive still in The images from his glasses of his elder broth- MARVEL®-Phile in this, the second half of er, Chuck, merge into a gestalt being our quest to bring you characters from known as 3-D Man. the dusty pages of Marvel Comics past. As 3-D Man can remain active for only the aforementioned miniseries is showing three hours at a time, after which he must readers new and old, just because a char- split into his composite images and return acter hasnt been seen in a while certainly Hals mind to his body. While active, 3-D doesnt mean he lacks potential. This is the Mans brain is a composite of the minds of case with our two intrepid heroes for this both Hal and Chuck Chandler, with Chuck month, 3-D Man and the Blue Shield. -

Marvel September to December 2021

MARVEL Marvel's Black Widow: The Art of the Movie Marvel Comics Summary After seven appearances, spanning a decade in the Marvel Cinematic Universe, Natasha Romanoff , a.k.a. the Black Widow, takes the lead in an adventure unlike any other she's known before. Continuing their popular ART OF series of movie tie-in books, Marvel presents another blockbuster achievement! Featuring exclusive concept artwork and in-depth interviews with the creative team, this deluxe volume provides insider details about the making of the highly anticipated film. Marvel 9781302923587 On Sale Date: 11/23/21 $50.00 USD/$63.00 CAD Hardcover 288 Pages Carton Qty: 16 Ages 0 And Up, Grades P to 17 Comics & Graphic Novels / Superheroes CGN004080 27.6 cm H | 18.4 cm W The Marvels Vol. 1 Kurt Busiek, Yildiray Cinar Summary Kurt Busiek (MARVELS) is back, with the biggest, wildest, most sprawling series you’ve ever seen — telling stories that span decades and range from cosmic adventure to intense human drama, from street-level to the far reaches of space, starring literally anyone from Marvel’s very first heroes to the superstars of tomorrow! Featuring Captain America, Spider-Man, the Punisher, the Human Torch, Storm, the Black Cat, the Golden Age Vision, Melinda May, Aero, Iron Man, Thor and many more — and introducing two brand-new characters destined to be fan-favorites — a thriller begins that will take readers across the Marvel Universe…and beyond! Get to know Kevin Schumer, an ordinary guy with some big secrets — and the mysterious Threadneedle as well! But who (or what) is KSHOOM? It all starts here. -

Songs of Wintter Watts, Composer and Sara Teasdale, Poet

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Theses and Dissertations--Music Music 2017 WHEN UNEXPECTED BEAUTY BURNS LIKE SUNLIGHT ON THE SEA: SONGS OF WINTTER WATTS, COMPOSER AND SARA TEASDALE, POET Casey A. Huggins University of Kentucky, [email protected] Digital Object Identifier: https://doi.org/10.13023/ETD.2017.037 Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Huggins, Casey A., "WHEN UNEXPECTED BEAUTY BURNS LIKE SUNLIGHT ON THE SEA: SONGS OF WINTTER WATTS, COMPOSER AND SARA TEASDALE, POET" (2017). Theses and Dissertations--Music. 78. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/music_etds/78 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Music at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations--Music by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT AGREEMENT: I represent that my thesis or dissertation and abstract are my original work. Proper attribution has been given to all outside sources. I understand that I am solely responsible for obtaining any needed copyright permissions. I have obtained needed written permission statement(s) from the owner(s) of each third-party copyrighted matter to be included in my work, allowing electronic distribution (if such use is not permitted by the fair use doctrine) which will be submitted to UKnowledge as Additional File. I hereby grant to The University of Kentucky and its agents the irrevocable, non-exclusive, and royalty-free license to archive and make accessible my work in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known. -

Balranald’S 5 Rivers Outback Festival – BALRANALD NSW

MEDIA RELEASE: WENDY MATTHEWS ANNOUNCES TOUR AND NEW ALBUM October 13: Balranald’s 5 Rivers Outback Festival – BALRANALD NSW WENDY MATTHEWS is thrilled to announce her brand new album The Welcome Fire will be released August 23. The Welcome Fire is Wendy’s first original album in 12 years. Wendy will perform songs from the album LIVE from September 1st. The Welcome Fire is released through Fanfare Records and is out August 23. Tickets for the LIVE shows are on sale now. Beautifully evocative and superbly crafted, The Welcome Fire is an album filled with personal, poignant lyrics and reflective melodies. The album is undoubtedly contemporary in sound, yet the voice is unmistakably that of Wendy Matthews. The Welcome Fire not only re-establishes Wendy as one of Australia’s most influential and iconic voices and artists but also marks a new chapter in her career. There are very few artists in Australia who can come close to Wendy Matthews and her stunning credentials; seven Arias, a massive 19 hit singles, and seven platinum-plus selling albums. Her career-defining album Lily sold over 500,000 albums and over 300,000 singles of her now signature song The Day You Went Away when released in the mid 1990’s. The Live shows will feature Wendy performing some of her biggest hits including Standing Strong, The Day You Went Away , If Only I Could , Token Angels , Fridays Child & I Don’t Want To Be With Nobody But You as well as tracks from the new album. Don’t miss Wendy Matthews LIVE with her band at one of the following venues. -

Expressions 2021

EXPRESS 2021 ONS CONTRIBUTORS Ciara Alisha Emma Messick Deanna M. Auvil Michelle Metzgar Chloe Baldwin Donna J. Morgan Tony (Michael) Ballas Jordan Morral Brianna Bell William M. O’Boyle Ky Bittner Chloe Puffenberger 12401 Willowbrook Road, SE Samantha Blackstone Jason Rakaczewski Cumberland, MD 21502-2596 Wil Brauer Tyler Robinson www.allegany.edu Cami Cutter Phoebe Shuttleworth Rome Davis Michael Skelley Morgan Eberhart Marita Smith Zakiyah Felder Gracie Steele Gina Franciosi Shana Thomas Daniel Hickle Morgan White Angel Kifer Lisa L. Lease FACULTY EDITOR Dr. Tino Wilfong ARTWORK FEATURED ON FRONT/BACK COVER: ASSISTANT EDITOR (FOR POETRY) “Golden Cattails” Tony (Michael) Ballas Heather Greise STUDENT EDITOR Gina Franciosi ADVISORS Assoc. Prof. John A. Bone Jared Ritchey Prof. Robyn L. Price Suzanne Stultz EDITORIAL BOARD Marsha Clauson Janna Lee Gilbert Cochrum Kim Mouse Rachel Cofield Alicia Phillips Kathy Condor Shannon Redman Levi Feaster Roberta See Printed by: Sandi Foreman Nick Taylor Morgantown Printing & Binding Joshua Getz Spring Semester 2021 Jim House © 2021 Wendy Knopsnider TABLE OF CONTENTS Student Editor’s Introduction...................................... 5 Artwork & Photography Golden Cattails | Tony (Michael) Ballas................Front/Back Cover Sea Seeker | Michelle Metzgar ................................. 8 Little Wrangler | Brianna Bell .................................. 15 Nature’s Water Slide | Shana Thomas ........................... 20 Antique Car | Morgan White .................................. 26 Black and -

Cities Without Citizens Edited by Eduardo Cadava and Aaron Levy

Cities Without Citizens Edited by Eduardo Cadava and Aaron Levy Contributions by: Giorgio Agamben, Arakawa + Gins, Branka Arsic, Eduardo Cadava, Joan Dayan, Gans & Jelacic Architecture, Thomas Keenan, Gregg Lambert, Aaron Levy, David Lloyd, Rafi Segal Eyal Weizman Architects, Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak. Slought Books, Philadelphia with the Rosenbach Museum & Library Theory Series, No. 1 Copyright © 2003 by Aaron Levy and Eduardo Cadava, Slought Foundation. All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book, or parts thereof, in any form, without written permission from Slought Books, a division of Slought Foundation. No part may be stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without prior written permission, except in the case of brief quotations in reviews for inclusion in a magazine, newspaper, or broadcast. This project was made possible through the Vanguard Group Foundation and the 5-County Arts Fund, a Pennsylvania Partners in the Arts program of the Pennsylvania Council on the Arts, a state agency. It is funded by the citizens of Pennsylvania through an annual legislative appropriation, and administered locally by the Greater Philadelphia Cultural Alliance. The Pennsylvania Council on the Arts is supported by the National Endowment for the Arts, a federal agency. Additional support for the 5-County Arts Fund is provided by the Delaware River Port Authority and PECO energy. We also acknowledge the financial support of the Memorial Foundation for Jewish Culture, NY for Aaron Levy’s Kloster Indersdorf series, and the International Artists’ Studio Program in Sweden (IASPIS) for Lars Wallsten’s Crimescape series. -

Urban Swaras Running Club Newsletter, November 2019

URBAN SWARAS RUNNING CLUB USRC NEWSLETTER | NOVEMBER 2019 | ISSUE NO. 008 MARATHON TOURISM CONTENTS EDITOR’S NOTE Hello Swaras, As we draw a close to the year, we would like to congratulate everyone 1. VICTOR KAMAU - THE ULTRA KING who pushed their running limits this Just who is this man? Is he human? Read his story that will leave you year. utterly gobsmacked! We are delighted to share with you 10. TOR DES GÉANTS amazing stories from Swaras who What does it take to run this 356 km endurance trail race? Victor Kamau have dared to go the extra mile (for breaks it down. some, quite literally) to achieve their goals. Thank you Victor, Claire, Lyma, 12. MOUNTAIN TO MOUNTAIN Daisy, Ngari, Nyaruai, Muchina, Claire Baker give her account of the club’s annual Ultra Marathon. Waichigo, Eric, Rosemary, Cheruiyot and Josiah for your stories. 16. BREAKING LIMITS Once again, Lyma Mwangi is set up for an imaginable challenge by her As you can see, this issue is probably husband Peter. She survived it to tell us how it unfolded. one of the longest we’ve done - 13 articles deep. So we suggest that you 20. AGAINST ALL ODDS - BERLIN’S PB! get yourself comfortable - relax put Read about Daisy Ajima’s fabulous performance at this year’s Berlin your feet up, drink of choice in hand Marathon. and settle in to enjoy the exciting read. 22. NGARI MAHIHU Ngari comes out of the shadows and gives us a glimpse into his running Best wishes in the remaining runs escapades. -

Science Fiction Review 42 Geis 1971-01

NUMBER 42 — JANUARY 1971 SCIENCE FICTION REVIEW COVER-------------------------------------------------- TIM KIRK P.O. Box 3116 Santa Monica, Cal. 90403 DIALOG by Geis-&-Geis: a blue jaunt into Hugo nominations..................................... 4 SCIENCE FICTION IN AN AGE OF REVOLUTION by Robert Edited and Published by RICHARD E. GEIS (213) ^51-9206 Silverberg. Tne muscle and bones of his Heicon EIGHT TIMES A YEAR Guest of Honor Speech.......................................... 6 SUBSCRIPTIONS: 50? each issue for as many as you wish to pay OPEN LETTER by Robert A. W. Lowndes. Thoughts for in advance, in the U.S.A., Canada and Australia. But from one of the First.................................. .........9 please pay from Canada in Canadian P.O. Money Orders in U.S. OFF THE DEEP END by Piers Anthony. A column dollars. $8.00 for two years — $4.00 for one year. dealing with Robert Moore Williams and FIRST CLASS RATE: 75? per issue in U.S.A, and Canada. $1.00 L. Ron Hubbard....................... 15 per issue overseas. These rates subject to change. THE WARLORDS OF KRISHNA by John Boardman. L. Sprague de Camp take notice.............................. 19 SFR's Agents Overseas— "MEANWHILE, BACK AT THE NEWSSTAND..." by David Ethel Lindsay Hans J. Alpers B. Williams. A column of prozine commentary......23 Courage House D—285 Bremerhaven 1 6 Langley Ave. Weissenburger Str. 6 THE AUTHOR IN SEARCH OF A PUBLISHER by Greg Surbiton, Surrey, WEST GERMANY Benford. How to be a pro................................. ...25 UNITED KINGDOM WEST GERMAN RATES: BOOK REVIEWS by guest reviewer Norman Spirrrad U.K. RATES: 2DM per issue—16DM Yr. and the gold-plated regulars: Paul Walker 4/- or 5 for 1 pound Richard Delap ’ Fred Patten Ulf Westblom John Foyster Ted Pauls Studentbacken 25C/103 12 Glengariff Dr.