Songs of Wintter Watts, Composer and Sara Teasdale, Poet

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Louis Nicholas Song Collection

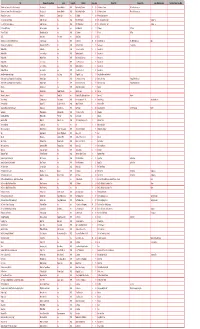

Title Composer/Arranger/Editor Lyricist Copyright Publisher Pages Box Original Title Translated Title Larger Work/Collection Translated Title of Large Work A Menina e a Cancao (Fillette et la Chanson, La) Villa-Lobos, H. Andrade, Mario de 1925 Max Eschig & Cie Edrs 12 25 A Menina e a Cancao Fillette et la Chanson, La A Menina e a Cancao (Fillette et la Chanson, La), c.2 Villa-Lobos, H. Andrade, Mario de 1925 Max Eschig & Cie Edrs 12 25 A Menina e a Cancao Fillette et la Chanson, La A Notre Dame sous-terre Chatillon, E. Chastel, Guy n/a E. Chatillon 7 30 A Notre Dame sous-terre A Te, O Cara, Amore Talora Bellini, Vincenzo n/a 1946 Pro Art Publications 4 29 A Te, O Cara, Amore Talora Puritans, The A Te, O Cara, Amore Talora, c.2 Bellini, Vincenzo n/a 1946 Pro Art Publications 4 29 A Te, O Cara, Amore Talora Puritans, The A Trianon (At Trianon) Holmes, Augusta n/a n/a Harch Music Co. 4 19 A Trianon At Trianon A Vous (To Thee) D'Hardelot and Boyer n/a 1895 G. Schirmer 4 17 A Vous To Thee A.B.C. Parry, John Parry, John n/a Oliver Ditson 5 23 A.B.C. Abborrita rivale, L' (She, My Rival Detested) Verdi, Giuseppe n/a 1915 G. Schirmer 10 28 Abborrita rivale, L' She, My Rival Detested Aida Abendsegen (Evening-Prayer) Humperdinck and Wette n/a 1894 B. Schott's Sohne 2 28 Abendsegen Evening-Prayer Abide with Me Ashford, E.L. -

Howard Willard Cook, Our Poets of Today

MODERN AMERICAN WRITERS OUR POETS OF TODAY Our Poets of Today BY HOWARD WILLARD COOK NEW YORK MOFFAT, YARD & COMPANY 1919 COPYRIGHT, 1918, BY MOFFAT, YARP & COMPANY C77I I count myself in nothing else so happy as in a soul remembering my good friends: JULIA ELLSWORTH FORD WITTER BYNNER KAHLIL GIBRAN PERCY MACKAYE 4405 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS To our American poets, to the publishers and editors of the various periodicals and books from whose pages the quotations in this work are taken, I wish to give my sincere thanks for their interest and co-operation in making this book possible. To the following publishers I am obliged for the privilege of using selections which appear, under their copyright, and from which I have quoted in full or in part: The Macmillan Company: The Chinese Nightingale, The Congo and Other Poems and General Booth Enters Heaven by Vachel Lindsay, Love Songs by Sara Teasdale, The Road to Cas- taly by Alice Brown, The New Poetry and Anthology by Harriet Monroe and Alice Corbin Henderson, Songs and Satires, Spoon River Anthology and Toward the Gulf by Edgar Lee Masters, The Man Against the Sky and Merlin by Edwin Arlington Rob- inson, Poems by Percy MacKaye and Tendencies in Modern American Poetry by Am> Lowell. Messrs. Henry Holt and Company: Chicago Poems by Carl Sandburg, These Times by Louis Untermeyer, A Boy's Will, North of Boston and Mountain Interval by Robert Frost, The Old Road to Paradise by Margaret Widdener, My Ireland by Francis Carlin, and Outcasts in Beulah Land by Roy Helton. Messrs. -

81288967.6.Pdf

*v tmtmmmmmmmmm /'(^,:'.' •' ; i V I I IJailtj/l ]>oKMS OFl)SSIA>'. ' ^ TO TllE EDITOR OF THB NOllTH BBITI3H DAILT UAU.. Sir - In your iritùfuc on the traiislation o£ the poeuis of Ossian, in yesterJay's issue, I tìnd that both thu traniilatur and writer of the article have fallen into a vei-y curious mistake iu their transla- lation of the only Gaelic iiuotation thereiu, liaving remUred thcword "ahviil" intosails, in placeofeye in its proper signiiication, the word for sails being this connection "shiuil." The ciuotation will then read translated, keeping for the rest to the ' writt'r'tì text— •• Tliim eji', I) m.v frieii.l: is l.. iiie | Like lu-ifililtìDÌiii; ol' morn ..ut of c!..iiil. , wbiih, I think, is a inore apposite tìgure than tbe I other.—I am, &e., <Jae[.. I Ardrishaig, ".th J,inu.%ry. " [Tlie word in the original is " shiuil." ShuU" ia simijly a typographical error. The whole passage •willbefound in the " Fingal," Duan II.,bBtweon verse :!41 aml o.'il. It is the cxclamation of CuchuUin as he sees the war ships of Fiugal bearing down to. Iii8 aid on the Irish coast. If the werd ha.l be?n •' shuil" the remark ot our correspcjndent would be • iiuite accurate.—Ed. N.B.D.M.] : siiouiKj Bq'j ^vin a]qBqo.ia Bi qi sonapiAa uoa£) •(, Aiuo eq:) si gg^x 3« oiISE;) pa^uijd eqx 'paiisu •jnud ui iioi;'EM[qtid JI3IH mi\i aopjo i[onn] ein suuoj BBq ^diJOBUUEM •(Bqj joj 'iioa pa)utjdaa '[ ;u9eajd Jiaq; u; s~,xi\ OH-'^O ^'l^ ^'^'I^ E9Aoad peaa)iB si qoiqii '.i08T "! :)d!aosnuBra s,u"oEjaqdo- eouapiAa jo dtrjjB ouo ^ou puE 'oipEf) «[U0Bna9A -

WORLD HERITAGE and DISASTER Knowledge, Culture and Rapresentation Le Vie Dei Mercanti XV International Forum

Fabbrica della Conoscenza numero 71 Collana fondata e diretta da Carmine Gambardella Fabbrica della Conoscenza Collana fondata e diretta da Carmine Gambardella Scientific Committee: Carmine Gambardella, UNESCO Chair on Landscape, Cultural Heritage and Territorial Governance President and CEO of Benecon, Past-Director of the Department of Architecture and Industrial Design University of Studies of Campania “Luigi Vanvitelli” Federico Casalegno, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Boston Massimo Giovannini, Professor, Università “Mediterranea”, Reggio Calabria Bernard Haumont, Ecole Nationale Supérieure d’Architecture, Paris-Val de Seine Alaattin Kanoglu, Head of the Department of Architecture, İstanbul Technical University David Listokin, Professor, co-director of the Center for Urban Policy Research of Rutgers University / Edward J. Bloustein School of Planning and Public Policy, USA Paola Sartorio, Executive Director, The U.S.- Italy Fulbright Commission Elena Shlienkova, Professor, Professor of Architecture and Construction Institute of Samara State Techni - cal University Isabel Tort Ausina, Director UNESCO Chair Forum University and Heritage, Universitat Politècnica De València UPV, Spain Nicola Pisacane, Professor of Drawing – Department of Architecture and Industrial Design_University of Studies of Campania “Luigi Vanvitelli” Head of the Master School of Architecture – Interior Design and for Autonomy Cour - ses -Department of Architecture and Industrial Design - University of Studies of Cam - pania “Luigi Vanvitelli” Pasquale Argenziano, Professor of Drawing – Department of Architecture and Industrial Design_University of Studies of Campania “Luigi Vanvitelli” Alessandra Avella, Professor of Drawing – Department of Architecture and Industrial Design_University of Studies of Campania “Luigi Vanvitelli” Alessandro Ciambrone, Ph.D. in Territorial Governance (Milieux, Cultures et Sociétés du passé et du présent – ED 395) Université Paris X UNESCO Vocations Patrimoine 2007-09 Fellow / FUL - BRIGHT Thomas Foglietta 2003-04 Rosaria Parente, Ph.D. -

Crossing Over: from Black Rhythm Blues to White Rock 'N' Roll

PART2 RHYTHM& BUSINESS:THE POLITICAL ECONOMY OF BLACKMUSIC Crossing Over: From Black Rhythm Blues . Publishers (ASCAP), a “performance rights” organization that recovers royalty pay- to WhiteRock ‘n’ Roll ments for the performance of copyrighted music. Until 1939,ASCAP was a closed BY REEBEEGAROFALO society with a virtual monopoly on all copyrighted music. As proprietor of the com- positions of its members, ASCAP could regulate the use of any selection in its cata- logue. The organization exercised considerable power in the shaping of public taste. Membership in the society was generally skewed toward writers of show tunes and The history of popular music in this country-at least, in the twentieth century-can semi-serious works such as Richard Rodgers and Lorenz Hart, Cole Porter, George be described in terms of a pattern of black innovation and white popularization, Gershwin, Irving Berlin, and George M. Cohan. Of the society’s 170 charter mem- which 1 have referred to elsewhere as “black roots, white fruits.’” The pattern is built bers, six were black: Harry Burleigh, Will Marion Cook, J. Rosamond and James not only on the wellspring of creativity that black artists bring to popular music but Weldon Johnson, Cecil Mack, and Will Tyers.’ While other “literate” black writers also on the systematic exclusion of black personnel from positions of power within and composers (W. C. Handy, Duke Ellington) would be able to gain entrance to the industry and on the artificial separation of black and white audiences. Because of ASCAP, the vast majority of “untutored” black artists were routinely excluded from industry and audience racism, black music has been relegated to a separate and the society and thereby systematically denied the full benefits of copyright protection. -

Maritime Carrier's Liability for Loss of Or Damage to Goods Under The

Maritime Carrier's Liability for Loss of or Damage to Goods under the Hague Rules, Visby Rules and the Hamburg Rules, compared with his Liability as an Operator under the Relevant Rules of the International Multimodal Transport Convention. A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Hani M.S. Abdulrahim The School of Law, Faculty of Law and Financial Studies, University of Glasgow February 1994 © Hani M.S. Abdulrahim, 1994 ProQuest Number: 11007904 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 11007904 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 “ILhl m i GLASGOW C>p I UNIVERr'T library ii To My mother, brothers, sisters and in memory of my father. Acknowledgements I wish with considerable enthusiasm to acknowledge and express my deepest grateful thanks and gratitude to Dr. W. Balekjian and Mr Alan Gamble for their invaluable guidance and encouragement in supervising this thesis. They have given unsparingly of their time to it. It gives me great pleasure to acknowledge the helpfulness of the Glasgow University library staff, and also my deep gratitude to Mrs Cara Wilson who kindly typed this work. -

Final Draft with PQ Edits

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Santa Barbara Liebe und Leben: Exploring Gender Roles and Sexuality in Nineteenth-Century Lieder A supporting document submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Musical Arts in Music by Tyler Michael-Anthony Reece Committee in charge: Professor Benjamin Brecher, Chair Professor Isabel Bayrakdarian Professor Linda Di Fiore Professor Stefanie Tcharos June 2019 The supporting document of Tyler Michael-Anthony Reece is approved. Linda Di Fiore Stefanie Tcharos Isabel Bayrakdarian Benjamin Brecher, Committee Chair May 2019 Liebe und Leben: Exploring Gender Roles and Sexuality in Nineteenth-Century Lieder Copyright © 2019 by Tyler Michael-Anthony Reece iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank the members of my committee, Professors Benjamin Brecher, Isabel Bayrakdarian, Stephanie Tcharos, and Dr. Linda Di Fiore for their devotion and lending of expertise with regard to this project. A special thanks to Professor Stefanie Tcharos, who so willingly guided my research and kept me focused during the writing on this document, despite my being outside of the musicology area. And to Dr. Linda Di Fiore, my teacher and mentor, whom I owe an immense amount of gratitude. Her unwavering support and leadership have positively influenced my abilities as a singer, scholar, and member of the arts community. Without her, I would not be where I am today. Finally, I want to thank my friends and family who kept me smiling during the stressful moments along the way. I hope that I am able to provide -

I839 - ICA: Investigation Opened Into an Alleged Anticompetitive Agreement in the Transport of Fuel and Waste to and from the Campanian Archipelago

04/02/2020 AGCM - Autorita' Garante della Concorrenza e del Mercato (/en/) Follow us on (https://twitter.com/ (https://www.fac (https://ww (/rss/ato (htt Search... Advanced search (http://en.agcm.it/en/search?searchword=) You are in: Home (/en) / Media (/en/media) / Press releases (/en/media/press-releases) / ICA: investigation opened into an alleged anticompetitive agreement in the transport of fuel and waste to and from the Campanian Archipelago I839 - ICA: investigation opened into an alleged anticompetitive agreement in the transport of fuel and waste to and from the Campanian Archipelago PRESS RELEASE On 14 January 2020, the Authority opened an investigation against the companies Mediterranea Marittima S.p.a., Servizi Marittimi Liberi Giuré & Lauro S.r.l., Medmar Navi S.p.a., Tra.Spe.Mar. S.r.l, GML Trasporti Marittimi S.r.l and Consorzio COTRASIR to assess an alleged agreement restricting competition in the market for the transport of ammable material and waste to and from the islands in the Gulf of Naples (Ischia, Procida and Capri), in breach ofArticle 2 of Law no. 287/90 and/or Article 101 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union.. Also based on the numerous complaints received, the Authority has in fact considered that the strategy with which the two competitors Mediterranea Marittima (holding company that controls the operating company Medmar Navi) and Servizi Marittimi Liberi Giuré & Lauro, after creating the joint venture GML, have set up the COTRASIR consortium between the latter and the third operator -

ABSTRACT Reading Dreams: an Audience-Critical Approach to the Dreams in the Gospel of Matthew Derek S. Dodson, B.A., M.Div

ABSTRACT Reading Dreams: An Audience-Critical Approach to the Dreams in the Gospel of Matthew Derek S. Dodson, B.A., M.Div. Mentor: Charles H. Talbert, Ph.D. This dissertation seeks to read the dreams in the Gospel of Matthew (1:18b-25; 2:12, 13-15, 19-21, 22; 27:19) as the authorial audience. This approach requires an understanding of the social and literary character of dreams in the Greco-Roman world. Chapter Two describes the social function of dreams, noting that dreams constituted one form of divination in the ancient world. This religious character of dreams is further described by considering the practice of dreams in ancient magic and Greco-Roman cults as well as the role of dream interpreters. This chapter also includes a sketch of the theories and classification of dreams that developed in the ancient world. Chapters Three and Four demonstrate the literary dimensions of dreams in Greco-Roman literature. I refer to this literary character of dreams as the “script of dreams;” that is, there is a “script” (form) to how one narrates or reports dreams in ancient literature, and at the same time dreams could be adapted, or “scripted,” for a range of literary functions. This exploration of the literary representation of dreams is nuanced by considering the literary form of dreams, dreams in the Greco-Roman rhetorical tradition, the inventiveness of literary dreams, and the literary function of dreams. In light of the social and literary contexts of dreams, the dreams of the Gospel of Matthew are analyzed in Chapter Five. -

Crane Meadows National Wildlife Refuge Environmental Assessment

United States Department of the Interior NSH A¡ID WILDLIFE SERVICE Bishop Henry Whipple Fedcral Buitding I Fedcral Drive Fort Snelling, MN 55lll-4056 IN REILYNEFEN,T(} NWRS/CP Jlur:re29,2010 Dear Reviewer: We are pleased to provide you with this Draft Comprehensive Conservation Plan (CCP) and Environmental Assessment (EA) for Crane Meadows National Wildlife Refuge (NWR). Crane Meadows NWR was established in 1992 for'... the conservation of the wetlands of the Nation...' under the Emergency'Wetland Resources Act of 1986. The Service owns and manages approximately 1,800 acres of 13,540 acres proposed for acquisition in Morrison County, Minnesota. The unique wetland complex contains rare and declining habitat types, important archaeological resources, a diversity of local and migratory species, and an abundance of recreational opportunities. The CCP will guide management of the Refuge for the next 15 years and will help the Refuge meet its purpose and contribute to the mission of the National V/ildlife Refuge System. The CCP will provide both broad and specific guidance on various issues; describe the Refuge's vision, goals, and measurable objectives; and list strategies for reaching the objectives. We invite you to review and comment on the Draft CCP and EA. By sharing your thoughts, you can help ensure that the final CCP is both visionary and practical. V/e will host an open house where you will be able to ask questions and voice concerns and suggestions. This event will take place in the Refuge maintenance building from2 p.m. - 7 p.m. on Tuesday, July 20,2010. -

Appendix B: a Literary Heritage I

Appendix B: A Literary Heritage I. Suggested Authors, Illustrators, and Works from the Ancient World to the Late Twentieth Century All American students should acquire knowledge of a range of literary works reflecting a common literary heritage that goes back thousands of years to the ancient world. In addition, all students should become familiar with some of the outstanding works in the rich body of literature that is their particular heritage in the English- speaking world, which includes the first literature in the world created just for children, whose authors viewed childhood as a special period in life. The suggestions below constitute a core list of those authors, illustrators, or works that comprise the literary and intellectual capital drawn on by those in this country or elsewhere who write in English, whether for novels, poems, nonfiction, newspapers, or public speeches. The next section of this document contains a second list of suggested contemporary authors and illustrators—including the many excellent writers and illustrators of children’s books of recent years—and highlights authors and works from around the world. In planning a curriculum, it is important to balance depth with breadth. As teachers in schools and districts work with this curriculum Framework to develop literature units, they will often combine literary and informational works from the two lists into thematic units. Exemplary curriculum is always evolving—we urge districts to take initiative to create programs meeting the needs of their students. The lists of suggested authors, illustrators, and works are organized by grade clusters: pre-K–2, 3–4, 5–8, and 9– 12. -

Title "Stand by Your Man/There Ain't No Future In

TITLE "STAND BY YOUR MAN/THERE AIN'T NO FUTURE IN THIS" THREE DECADES OF ROMANCE IN COUNTRY MUSIC by S. DIANE WILLIAMS Presented to the American Culture Faculty at the University of Michigan-Flint in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Liberal Studies in American Culture Date 98 8AUGUST 15 988AUGUST Firs t Reader Second Reader "STAND BY YOUR MAN/THERE AIN'T NO FUTURE IN THIS" THREE DECADES OF ROMANCE IN COUNTRY MUSIC S. DIANE WILLIAMS AUGUST 15, 19SB TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface Introduction - "You Never Called Me By My Name" Page 1 Chapter 1 — "Would Jesus Wear A Rolen" Page 13 Chapter 2 - "You Ain’t Woman Enough To Take My Man./ Stand By Your Man"; Lorrtta Lynn and Tammy Wynette Page 38 Chapter 3 - "Think About Love/Happy Birthday Dear Heartache"; Dolly Parton and Barbara Mandrell Page 53 Chapter 4 - "Do Me With Love/Love Will Find Its Way To You"; Janie Frickie and Reba McEntire F'aqe 70 Chapter 5 - "Hello, Dari in"; Conpempory Male Vocalists Page 90 Conclusion - "If 017 Hank Could Only See Us Now" Page 117 Appendix A - Comparison Of Billboard Chart F'osi t i ons Appendix B - Country Music Industry Awards Appendix C - Index of Songs Works Consulted PREFACE I grew up just outside of Flint, Michigan, not a place generally considered the huh of country music activity. One of the many misconception about country music is that its audience is strictly southern and rural; my northern urban working class family listened exclusively to country music. As a teenager I was was more interested in Motown than Nashville, but by the time I reached my early thirties I had became a serious country music fan.