In Defense and Appreciation of the Rap Music Mixtape As “National” and “Dissident” Communication

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Before the FEDERAL TRADE COMMISSION Washington, DC 20580

Before the FEDERAL TRADE COMMISSION Washington, DC 20580 In the Matter of ) ) Request for Public Comment on the ) P104503 Federal Trade Commission’s ) Implementation of the Children’s Online ) Privacy Protection Rule ) COMMENTS OF The Center for Digital Democracy, American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, American Academy of Pediatrics, Benton Foundation, Berkeley Media Studies Group, Campaign for a Commercial-Free Childhood, Center for Science in the Public Interest, Children Now, Consumer Action, Consumer Federation of America, Consumer Watchdog, Consumers Union, National Consumers League, Privacy Rights Clearinghouse, Public Health Institute, U.S. PIRG, and World Privacy Forum Of Counsel: Angela J. Campbell, Guilherme Roschke Pamela Hartka Institute for Public Representation James Kleier, Jr. Georgetown University Law Center Raquel Kellert 600 New Jersey Avenue, NW Andrew Lichtenberg Washington, DC 20001 Ari Meltzer (202) 662-9535 Georgetown Law Students Attorneys for CDD et al. June 30, 2010 SUMMARY The Center for Digital Democracy, American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, American Academy of Pediatrics, Benton Foundation, Berkeley Media Studies Group, Campaign for a Commercial-Free Childhood, Center for Science in the Public Interest, Children Now, Consumer Action, Consumer Federation of America, Consumer Watchdog, Consumers Union, National Consumers League, Privacy Rights Clearinghouse, Public Health Institute, U.S. PIRG, and World Privacy Forum are pleased that the FTC has begun a comprehensive review of its children’s privacy regulations. In general, the Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act (COPPA) and the FTC rules implementing it have helped to protect the privacy and safety of children online. Recent developments in technology and marketing practices require that the COPPA rules be updated and clarified. -

The Video Game Industry an Industry Analysis, from a VC Perspective

The Video Game Industry An Industry Analysis, from a VC Perspective Nik Shah T’05 MBA Fellows Project March 11, 2005 Hanover, NH The Video Game Industry An Industry Analysis, from a VC Perspective Authors: Nik Shah • The video game industry is poised for significant growth, but [email protected] many sectors have already matured. Video games are a large and Tuck Class of 2005 growing market. However, within it, there are only selected portions that contain venture capital investment opportunities. Our analysis Charles Haigh [email protected] highlights these sectors, which are interesting for reasons including Tuck Class of 2005 significant technological change, high growth rates, new product development and lack of a clear market leader. • The opportunity lies in non-core products and services. We believe that the core hardware and game software markets are fairly mature and require intensive capital investment and strong technology knowledge for success. The best markets for investment are those that provide valuable new products and services to game developers, publishers and gamers themselves. These are the areas that will build out the industry as it undergoes significant growth. A Quick Snapshot of Our Identified Areas of Interest • Online Games and Platforms. Few online games have historically been venture funded and most are subject to the same “hit or miss” market adoption as console games, but as this segment grows, an opportunity for leading technology publishers and platforms will emerge. New developers will use these technologies to enable the faster and cheaper production of online games. The developers of new online games also present an opportunity as new methods of gameplay and game genres are explored. -

“Rapper's Delight”

1 “Rapper’s Delight” From Genre-less to New Genre I was approached in ’77. A gentleman walked up to me and said, “We can put what you’re doing on a record.” I would have to admit that I was blind. I didn’t think that somebody else would want to hear a record re-recorded onto another record with talking on it. I didn’t think it would reach the masses like that. I didn’t see it. I knew of all the crews that had any sort of juice and power, or that was drawing crowds. So here it is two years later and I hear, “To the hip-hop, to the bang to the boogie,” and it’s not Bam, Herc, Breakout, AJ. Who is this?1 DJ Grandmaster Flash I did not think it was conceivable that there would be such thing as a hip-hop record. I could not see it. I’m like, record? Fuck, how you gon’ put hip-hop onto a record? ’Cause it was a whole gig, you know? How you gon’ put three hours on a record? Bam! They made “Rapper’s Delight.” And the ironic twist is not how long that record was, but how short it was. I’m thinking, “Man, they cut that shit down to fifteen minutes?” It was a miracle.2 MC Chuck D [“Rapper’s Delight”] is a disco record with rapping on it. So we could do that. We were trying to make a buck.3 Richard Taninbaum (percussion) As early as May of 1979, Billboard magazine noted the growing popularity of “rapping DJs” performing live for clubgoers at New York City’s black discos.4 But it was not until September of the same year that the trend gar- nered widespread attention, with the release of the Sugarhill Gang’s “Rapper’s Delight,” a fifteen-minute track powered by humorous party rhymes and a relentlessly funky bass line that took the country by storm and introduced a national audience to rap. -

The Mixtape: a Case Study in Emancipatory Journalism

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: THE MIXTAPE: A CASE STUDY IN EMANCIPATORY JOURNALISM Jared A. Ball, Doctor of Philosophy, 2005 Directed By: Dr. Katherine McAdams Associate Professor Philip Merrill College of Journalism Associate Dean, Undergraduate Studies During the 1970s the rap music mixtape developed alongside hip-hop as an underground method of mass communication. Initially created by disc-jockeys in an era prior to popular “urban” radio and video formats, these mixtapes represented an alternative, circumventing traditional mass medium. However, as hip-hop has come under increasing corporate control within a larger consolidated media ownership environment, so too has the mixtape had to face the challenge of maintaining its autonomy. This media ownership consolidation, vertically and horizontally integrated, has facilitated further colonial control over African America and has exposed as myth notions of democratizing media in an undemocratic society. Acknowledging a colonial relationship the writer created FreeMix Radio: The Original Mixtape Radio Show where the mixtape becomes both a source of free cultural expression and an anti-colonial emancipatory journalism developed as a “Third World” response to the needs of postcolonial nation-building. This dissertation explores the contemporary colonizing effects of media consolidation, cultural industry function, and copyright ownership, concluding that the development of an underground press that recognizes the tremendous disparities in advanced technological access (the “digital divide”) appears to be the only viable alternative. The potential of the mixtape to serve as a source of emancipatory journalism is studied via a three-pronged methodological approach: 1) An explication of literature and theory related to the history of and contemporary need for resistance media, 2) an analysis of the mixtape as a potential underground mass press and 3) three focus group reactions to the mixtape as resistance media, specifically, the case study of the writer’s own FreeMix Radio: The Original Mixtape Radio Show. -

Confessions of a Black Female Rapper: an Autoethnographic Study on Navigating Selfhood and the Music Industry

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University African-American Studies Theses Department of African-American Studies 5-8-2020 Confessions Of A Black Female Rapper: An Autoethnographic Study On Navigating Selfhood And The Music Industry Chinwe Salisa Maponya-Cook Georgia State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/aas_theses Recommended Citation Maponya-Cook, Chinwe Salisa, "Confessions Of A Black Female Rapper: An Autoethnographic Study On Navigating Selfhood And The Music Industry." Thesis, Georgia State University, 2020. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/aas_theses/66 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of African-American Studies at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in African-American Studies Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CONFESSIONS OF A BLACK FEMALE RAPPER: AN AUTOETHNOGRAPHIC STUDY ON NAVIGATING SELFHOOD AND THE MUSIC INDUSTRY by CHINWE MAPONYA-COOK Under the DireCtion of Jonathan Gayles, PhD ABSTRACT The following research explores the ways in whiCh a BlaCk female rapper navigates her selfhood and traditional expeCtations of the musiC industry. By examining four overarching themes in the literature review - Hip-Hop, raCe, gender and agency - the author used observations of prominent BlaCk female rappers spanning over five deCades, as well as personal experiences, to detail an autoethnographiC aCCount of self-development alongside pursuing a musiC career. MethodologiCally, the author wrote journal entries to detail her experiences, as well as wrote and performed an aCCompanying original mixtape entitled The Thesis (available on all streaming platforms), as a creative addition to the research. -

A Case Study on Merger of Skype and Microsoft

European Journal of Business, Economics and Accountancy Vol. 8, No. 1, 2020 ISSN 2056-6018 VALUATION OF TARGET FIRMS IN MERGERS AND ACQUISITIONS: A CASE STUDY ON MERGER OF SKYPE AND MICROSOFT Nguyen Vuong Bang Tam Thu Dau Mot University VIETNAM [email protected] ABSTRACT Mergers and acquisitions have become the most popular used methods of growth for the company and it’s one of the best ways to make a shortcut to get the success. They create the larger potential market share and open it up to a more diversified market, increase competitive advantage against competitors. It also allows firms to operate more efficiently and benefit both competition and consumers. However, there are also many cases that the synergy between acquiring company and acquired company failed. The most common reason is to not create synergy between both of them. In recent months, the merger between Microsoft and Skype is a very hot topic of analysts and viewers…etc. This acquisition presents a big opportunity for both firms, Skype give Microsoft a boost in the enterprise collaboration. To exchange for this synergy, Microsoft paid $8.5 billion in cash for Skype, the firm is not yet profitable. Skype revenue totaling $860 million last year and operating profit of $264 million, the company lost $6.9 million overall, according to documents filed with the SEC. Is that a good deal for Microsoft? Many analysts have different point of view but most of them have negative perspective. Research was to provide the analysis of Skype’s intrinsic value with an optimistic view of point about Skype’s future, Microsoft overpaid for Skype. -

(BHC) Will Be Held Friday, September 25, 2020 10:00 AM - 12:00 PM

BALDWIN HILLS CONSERVANCY NOTICE OF PUBLIC MEETING The meeting of the Baldwin Hills Conservancy (BHC) will be held Friday, September 25, 2020 10:00 AM - 12:00 PM Pursuant to Executive Order N-29-20 issued by Governor Gavin Newsom on March 17, 2020, certain provisions of the Bagley Keene Open Meeting Act are suspended due to a State of Emergency in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Consistent with the Executive Order, this public meeting will be conducted by teleconference and internet, with no public locations. Members of the public may dial into the teleconference and or join the meeting online at Zoom. Please click the link below to join the webinar: https://ca-water-gov.zoom.us/j/91443309377 Or Telephone, Dial: USA 214 765 0479 USA 8882780296 (US Toll Free) Conference code: 596019 Materials for the meeting will be available at the Conservancy website on the Meetings & Notices tab in advance of the meeting date. 10:00 AM - CALL TO ORDER – Keshia Sexton, Chair MEETING AGENDA PUBLIC COMMENTS ON AGENDA OR NON-AGENDA ITEMS SHOULD BE SUBMITTED BEFORE ROLL CALL Public Comment and Time Limits: Members of the public can make comments in advance by emailing [email protected] or during the meeting by following the moderator’s directions on how to indicate their interest in speaking. Public comment will be taken prior to action on agenda items and at the end of the meeting for non-agenda items. Individuals wishing to comment will be allowed up to three minutes to speak. Speaking times may be reduced depending upon the number of speakers. -

Game Developers Conference Europe Wrap, New Women’S Group Forms, Licensed to Steal Super Genre Break Out, and More

>> PRODUCT REVIEWS SPEEDTREE RT 1.7 * SPACEPILOT OCTOBER 2005 THE LEADING GAME INDUSTRY MAGAZINE >>POSTMORTEM >>WALKING THE PLANK >>INNER PRODUCT ART & ARTIFICE IN DANIEL JAMES ON DEBUG? RELEASE? RESIDENT EVIL 4 CASUAL MMO GOLD LET’S DEVELOP! Thanks to our publishers for helping us create a new world of video games. GameTapTM and many of the video game industry’s leading publishers have joined together to create a new world where you can play hundreds of the greatest games right from your broadband-connected PC. It’s gaming freedom like never before. START PLAYING AT GAMETAP.COM TM & © 2005 Turner Broadcasting System, Inc. A Time Warner Company. Patent Pending. All Rights Reserved. GTP1-05-116-104_mstrA_v2.indd 1 9/7/05 10:58:02 PM []CONTENTS OCTOBER 2005 VOLUME 12, NUMBER 9 FEATURES 11 TOP 20 PUBLISHERS Who’s the top dog on the publishing block? Ranked by their revenues, the quality of the games they release, developer ratings, and other factors pertinent to serious professionals, our annual Top 20 list calls attention to the definitive movers and shakers in the publishing world. 11 By Tristan Donovan 21 INTERVIEW: A PIRATE’S LIFE What do pirates, cowboys, and massively multiplayer online games have in common? They all have Daniel James on their side. CEO of Three Rings, James’ mission has been to create an addictive MMO (or two) that has the pick-up-put- down rhythm of a casual game. In this interview, James discusses the barriers to distributing and charging for such 21 games, the beauty of the web, and the trouble with executables. -

Makin' It Magazine's Member 50% Off Nerve Djs Promotion Packages

#NERVE DJS NerveDJs.Com was established by four prominent disc jockeys in Cleveland, Ohio. Not satisfied with simply getting music from a local record pool, these four disc jockeys established a union where local and regional disc jockeys could benefit from a union or an association of DJs and musicians in the area for the purpose of economic empowerment. The Association was incorporated in 2003. Nerve Djs realized that bringing disc jockeys together under one roof, an economic force to be reckoned with would be established in northern Ohio. After achieving immediate success, this philosophy was used to branch out to other states. Today, NerveDJs.Com has members around the world. The purpose of the Nerve DJs is not to just distribute promotional MP3s for establishing a music library, but again, to create an organization were both artists and disc jockeys would benefit economically by partnerships with each other and industry giants such as Monster Products, Rane, Stanton, Pioneer, Numark, Native Instruments, and other industry giants, audio manufacturers and software suppliers. Unlike record pools and MP3 pools that simply distribute promotional tracks to disc jockeys and those who claim to be disc jockeys, NerveDJs.Com boasts that they are providing a service that far outweighs anything that a MP3 pool and a record pool could ever provide. Since the early days of NerveDJs.com, we have presented showcases, conferences, tours, conference calls and workshops that demonstrate hands-on techniques from some of the biggest manufacturers of DJ Products. At our 2007 event Rane sponsored us and sent DJ Jazzy Jay to present the new TTM 57 Rane. -

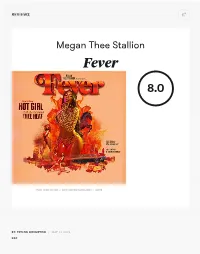

Megan Thee Stallion, Fever

REVIEWS Megan Thee Stallion Fever 8.0 1501 CERTIFIED / 300 ENTERTAINMENT • 2019 BY: TAYLOR CRUMPTON / MAY 23 2019 RAP Megan Thee Stallion’s debut is steeped in sex, pimpin, and power; it sounds like a once and future Houston rap classic. hen MeganMeganMegan TheeTheeThee StallionStallionStallion’s “Big Ole Freak” landed on Billboard’s Hot 100 in April, it was a testament to years of viral W freestyles and her devoted “hotties,” whose faithful support on social media helped the song rise to mainstream recognition. The 24- year-old has been prolific—her evolution is displayed through the invention of various rap personas, such as Tina Snow, Megan Thee Stallion, and Hot Girl Meg, the turn-up queen with serious ambition on her mind. “We have so many legends and so many greats,” she recently said of her hometown of Houston, Texas. “But I don’t feel like we ever really had a female rapper from Houston or Texas shut that shit down.” With her debut project Fever, she hopes to succeedMegan in doing Thee just Stallion that. At its core is the intersection of two beautiful rap legacies: the women rap tradition started by MCMCMC LyteLyteLyte and QueenQueenQueen LatifahLatifahLatifah, and Southern rap dynasty ushered in by Houston’s GetoGetoGeto BoysBoysBoys and UndergroundUndergroundUnderground KingsKingsKings. From the first song, Megan weaponizes misogynymisogynymisogyny through the execution of bars worthy of XXL Freshman Class President. South Park’s influence, home to fellow Houston legends ScarfaceScarfaceScarface and Lil’Lil’Lil’ KekeKekeKeke, is felt throughout “Hood Rat Shit,” which transitions into an ass-and clit-eating tutorial for her male tricks on “Pimpin,” where the spirit of Houston’s pimp tradition is embedded within every word. -

Dj Drama Mixtape Mp3 Download

1 / 2 Dj Drama Mixtape Mp3 Download ... into the possibility of developing advertising- supported music download services. ... prior to the Daytona 500. continued on »p8 No More Drama Will mixtape bust hurt hip-hop? ... Highway Companion Auto makers embrace MP3 Barsuk Backed Something ... DJ Drama's Bust Leaves Future Of The high-profile police raid.. Download Latest Dj Drama 2021 Songs, Albums & Mixtapes From The Stables Of The Best Dj Drama Download Website ZAMUSIC.. MP3 downloads (160/320). Lossless ... SoundClick fee (single/album). 15% ... 0%. Upload limits. Number of tracks. Unlimited. Unlimited. Unlimited. MP3 file.. Dec 14, 2020 — Bad Boy Mixtape Vol.4- DJ S S(1996)-mf- : Free Download. Free Romantic Music MP3 Download Instrumental - Pixabay. Lil Wayne DJ Drama .... On this special episode, Mr. Thanksgiving DJ Drama leader of the Gangsta Grillz movement breaks down how he changed the mixtape game! He's dropped .. Apr 16, 2021 — DJ Drama, Jacquees – ”QueMix 4′ MP3 DOWNLOAD. DJ Drama, Jacquees – ”QueMix 4′: DJ Drama join forces tithe music sensation .... Download The Dedication Lil Wayne MP3 · Lil Wayne:Dedication 2 (Full Mixtape)... · Lil Wayne - Dedication [Dedication]... · Dedicate... · Lil Wayne Feat. DJ Drama - .... Dj Drama Songs Download- Listen to Dj Drama songs MP3 free online. Play Dj Drama hit new songs and download Dj Drama MP3 songs and music album ... best blogs for downloading music, The Best of Music For Content Creators and ... SMASH THE CLUB | DJ Blog, Music Blog, EDM Blog, Trap Blog, DJ Mp3 Pool, Remixes, Edits, ... Dec 18, 2020 · blog Mix Blog Studio: The Good Kind of Drama.. Juelz Santana. -

BOONE-DISSERTATION.Pdf

Copyright by Christine Emily Boone 2011 The Dissertation Committee for Christine Emily Boone Certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Mashups: History, Legality, and Aesthetics Committee: James Buhler, Supervisor Byron Almén Eric Drott Andrew Dell‘Antonio John Weinstock Mashups: History, Legality, and Aesthetics by Christine Emily Boone, B.M., M.M. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin May 2011 Acknowledgements I want to first acknowledge those people who had a direct influence on the creation of this document. My brother, Philip, introduced me mashups a few years ago, and spawned my interest in the subject. Dr. Eric Drott taught a seminar on analyzing popular music where I was first able to research and write about mashups. And of course, my advisor, Dr. Jim Buhler has given me immeasurable help and guidance as I worked to complete both my degree and my dissertation. Thank you all so much for your help with this project. Although I am the only author of this dissertation, it truly could not have been completed without the help of many more people. First I would like to thank all of my professors, colleagues, and students at the University of Texas for making my time here so productive. I feel incredibly prepared to enter the field as an educator and a scholar thanks to all of you. I also want to thank all of my friends here in Austin and in other cities.