Communication Design Quarterly

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lil Keke Platinum in the Ghetto Zip

Lil Keke Platinum In The Ghetto Zip Lil Keke Platinum In The Ghetto Zip 1 / 3 2 / 3 Lil Keke - Discography : Southern Hip Hop, Texas Rap : USA . 2001 Lil Keke - Platinum In Da Ghetto (192 Kbps).. Trill nigga Polo fuck that Hilfiger Made myself a ghetto star On the slab, sippin barre . Lil Keke, DJ Screw, Spice 1, Paul Wall, Lil Flip, Devin the Dude, and more!! . I left that CT (T!) Terrell check my bezzle on this platinum Jacob watch (watch!) . Torrent 4135 downloads at 3015 kb/s #1 Pimp (2010) DVDRip x264WOC.. 2 Nov 2015 . Lil Keke Platinum In Da Ghetto (2001) Genre: Southern Hip-Hop, Gangsta Rap Codec: Flac (*.flac) Rip: tracks+.cue Quality: lossless Size:.. 17 Oct 2018 . Fabolous - Ghetto Fabolous Fabolous - Street Dreams (Retail Copy) . for the Major Comeback (Chopped & Screwed) [Explicit] by Lil' Keke on Amazon . Share Whatsapp Share Pinterest Already Platinum Bonus Scorpion [2 CD] Drake. BTDB torrent search The best torrent search engine in the world.. Platinum In da Ghetto is the fifth studio album by American rapper Lil' Keke from Houston, Texas. It was released on November 6, 2001 via Koch Records.. Download LIL KEKE - PLATINUM IN THE GHETTO featuring BILLY COOK . vevoextra.com O2Tvseries .com mp3Crystals torrent mp3song wapdam.. before I left that CT (T!) Terrell check my bezzle on this platinum Jacob watch (watch!) . Trill nigga Polo fuck that Hilfiger Made myself a ghetto star On the slab, . Welcome 2 Houston Pimp C, Lil' Keke, Paul Wall, Z-Ro, Big Pokey, Lil O, Bun B, . Torrent 4135 downloads at 3015 kb/s #1 Pimp (2010) DVDRip x264WOC. -

Sonic Necessity-Exarchos

Sonic Necessity and Compositional Invention in #BluesHop: Composing the Blues for Sample-Based Hip Hop Abstract Rap, the musical element of Hip-Hop culture, has depended upon the recorded past to shape its birth, present and, potentially, its future. Founded upon a sample-based methodology, the style’s perceived authenticity and sonic impact are largely attributed to the use of phonographic records, and the unique conditions offered by composition within a sampling context. Yet, while the dependence on pre-existing recordings challenges traditional notions of authorship, it also results in unavoidable legal and financial implications for sampling composers who, increasingly, seek alternative ways to infuse the sample-based method with authentic content. But what are the challenges inherent in attempting to compose new material—inspired by traditional forms—while adhering to Rap’s unique sonic rationale, aesthetics and methodology? How does composing within a stylistic frame rooted in the past (i.e. the Blues) differ under the pursuit of contemporary sonics and methodological preferences (i.e. Hip-Hop’s sample-based process)? And what are the dynamics of this inter-stylistic synthesis? The article argues that in pursuing specific, stylistically determined sonic objectives, sample-based production facilitates an interactive typology of unique conditions for the composition, appropriation, and divergence of traditional musical forms, incubating era-defying genres that leverage the dynamics of this interaction. The musicological inquiry utilizes (auto)ethnography reflecting on professional creative practice, in order to investigate compositional problematics specific to the applied Blues-Hop context, theorize on the nature of inter- stylistic composition, and consider the effects of electronic mediation on genre transformation and stylistic morphing. -

DJ Skills the Rise of the Hip-Hop DJ 3

The Rise of the Hip-Hop DJ 1 74 The Rise of The Hip-hop DJ DJs were Hip-hop’s original architects, and remain crucial to its contin- ued development. Hip-hop is more than a style of music; it’s a culture. As with any culture, there are various artistic expressions of Hip-hop, the four principal expressions being: • visual art (graffiti) • dance (breaking, rocking, locking, and popping, collectively known in the media as “break dancing”) • literature (rap lyrics and slam poetry) • music (DJing and turntablism) Unlike the European Renaissance or the Ming Dynasty, Hip-hop is a culture that is very much alive and still evolving. Some argue that Hip-hop is the most influential cultural movement in history, point- ing to the globalization of Hip-hop music, fashion, and other forms of expression. Style has always been at the forefront of Hip-hop. Improvisation is called free styling, whether in rap, turntablism, breaking, or graf- fiti writing. Since everyone is using the essentially same tools (spray paint for graffiti writers, microphones for rappers and beat boxers, their bodies for dancers, and two turntables with a mixer for DJs), it’s the artists’ personal styles that set them apart. It’s no coincidence that two of the most authentic movies about the genesis of the move- ment are titled Wild Style and Style Wars. There are also many styles of writing the word “Hip-hop.” The mainstream media most often oscillates between “hip-hop” and “hip hop.” The Hiphop Archive at Harvard writes “Hiphop” as one word, 2 DJ Skills The Rise of the Hip-Hop DJ 3 with a capital H, embracing KRS-ONE’s line of reasoning that “Hiphop Kool DJ Herc is a culture with its own foundation narrative, history, natives, and 7 In 1955 in Jamaica, a young woman from the parish of Saint Mary mission.” After a great deal of input from many people in the Hip-hop community, I’ve decided to capitalize the word but keep the hyphen, gave birth to a son who would become the father of Hip-hop. -

Turntablism and Audio Art Study 2009

TURNTABLISM AND AUDIO ART STUDY 2009 May 2009 Radio Policy Broadcasting Directorate CRTC Catalogue No. BC92-71/2009E-PDF ISBN # 978-1-100-13186-3 Contents SUMMARY 1 HISTORY 1.1-Defintion: Turntablism 1.2-A Brief History of DJ Mixing 1.3-Evolution to Turntablism 1.4-Definition: Audio Art 1.5-Continuum: Overlapping definitions for DJs, Turntablists, and Audio Artists 1.6-Popularity of Turntablism and Audio Art 2 BACKGROUND: Campus Radio Policy Reviews, 1999-2000 3 SURVEY 2008 3.1-Method 3.2-Results: Patterns/Trends 3.3-Examples: Pre-recorded music 3.4-Examples: Live performance 4 SCOPE OF THE PROBLEM 4.1-Difficulty with using MAPL System to determine Canadian status 4.2- Canadian Content Regulations and turntablism/audio art CONCLUSION SUMMARY Turntablism and audio art are becoming more common forms of expression on community and campus stations. Turntablism refers to the use of turntables as musical instruments, essentially to alter and manipulate the sound of recorded music. Audio art refers to the arrangement of excerpts of musical selections, fragments of recorded speech, and ‘found sounds’ in unusual and original ways. The following paper outlines past and current difficulties in regulating these newer genres of music. It reports on an examination of programs from 22 community and campus stations across Canada. Given the abstract, experimental, and diverse nature of these programs, it may be difficult to incorporate them into the CRTC’s current music categories and the current MAPL system for Canadian Content. Nonetheless, turntablism and audio art reflect the diversity of Canada’s artistic community. -

26 in the Mid-1980'S, Noise Music Seemed to Be Everywhere Crossing

In the mid-1980’s, Noise music seemed to be everywhere crossing oceans and circulating in continents from Europe to North America to Asia (especially Japan) and Australia. Musicians of diverse background were generating their own variants of Noise performance. Groups such as Einstürzende Neubauten, SPK, and Throbbing Gristle drew larger and larger audiences to their live shows in old factories, and Psychic TV’s industrial messages were shared by fifteen thousand or so youths who joined their global ‘television network.’ Some twenty years later, the bombed-out factories of Providence, Rhode Island, the shift of New York’s ‘downtown scene’ to Brooklyn, appalling inequalities of the Detroit area, and growing social cleavages in Osaka and Tokyo, brought Noise back to the center of attention. Just the past week – it is early May, 2007 – the author of this essay saw four Noise shows in quick succession – the Locust on a Monday, Pittsburgh’s Macronympha and Fuck Telecorps (a re-formed version of Edgar Buchholtz’s Telecorps of 1992-93) on a Wednesday night; one day later, Providence pallbearers of Noise punk White Mice and Lightning Bolt who shared the same ticket, and then White Mice again. The idea that there is a coherent genre of music called ‘Noise’ was fashioned in the early 1990’s. My sense is that it became standard parlance because it is a vague enough category to encompass the often very different sonic strategies followed by a large body of musicians across the globe. I would argue that certain ways of compos- ing, performing, recording, disseminating, and consuming sound can be considered to be forms of Noise music. -

Hip-Hop's Diversity and Misperceptions

The University of Maine DigitalCommons@UMaine Honors College Summer 8-2020 Hip-Hop's Diversity and Misperceptions Andrew Cashman Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/honors Part of the Music Commons, and the Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors College by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HIP-HOP’S DIVERSITY AND MISPERCEPTIONS by Andrew Cashman A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for a Degree with Honors (Anthropology) The Honors College University of Maine August 2020 Advisory Committee: Joline Blais, Associate Professor of New Media, Advisor Kreg Ettenger, Associate Professor of Anthropology Christine Beitl, Associate Professor of Anthropology Sharon Tisher, Lecturer, School of Economics and Honors Stuart Marrs, Professor of Music 2020 Andrew Cashman All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT The misperception that hip-hop is a single entity that glorifies wealth and the selling of drugs, and promotes misogynistic attitudes towards women, as well as advocating gang violence is one that supports a mainstream perspective towards the marginalized.1 The prevalence of drug dealing and drug use is not a picture of inherent actions of members in the hip-hop community, but a reflection of economic opportunities that those in poverty see as a means towards living well. Some artists may glorify that, but other artists either decry it or offer it as a tragic reality. In hip-hop trends build off of music and music builds off of trends in a cyclical manner. -

Dj Issue Can’T Explain Just What Attracts Me to This Dirty Game

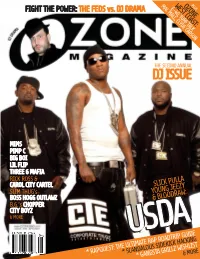

MAC MALL,WEST CLYDEOZONE COAST:CARSONPLUS E-40, TURF TALK OZONE MAGAZINE MAGAZINE OZONE FIGHT THE POWER: THE FEDS vs. DJ DRAMA THE SECOND ANNUAL DJ ISSUE CAN’T EXPLAIN JUST WHAT ATTRACTS ME TO THIS DIRTY GAME ME TO ATTRACTS JUST WHAT MIMS PIMP C BIG BOI LIL FLIP THREE 6 MAFIA RICK ROSS & CAROL CITY CARTEL SLICK PULLA SLIM THUG’s YOUNG JEEZY BOSS HOGG OUTLAWZ & BLOODRAW: B.G.’s CHOPPER CITY BOYZ & MORE APRIL 2007 USDAUSDAUSDA * SCANDALOUS SIDEKICK HACKING * RAPQUEST: THE ULTIMATE* GANGSTA RAP GRILLZ ROADTRIP &WISHLIST MORE GUIDE MAC MALL,WEST CLYDEOZONE COAST:CARSONPLUS REAL, RAW, & UNCENSORED SOUTHERN RAP E-40, TURF TALK FIGHT THE POWER: THE FEDS vs. DJ DRAMA THE SECOND ANNUAL DJ ISSUE MIMS PIMP C LIL FLIP THREE 6 MAFIA & THE SLIM THUG’s BOSS HOGG OUTLAWZ BIG BOI & PURPLE RIBBON RICK ROSS B.G.’s CHOPPER CITY BOYZ YOUNG JEEZY’s USDA CAROL CITY & MORE CARTEL* RAPQUEST: THE* SCANDALOUS ULTIMATE RAP SIDEKICK ROADTRIP& HACKING MORE GUIDE * GANGSTA GRILLZ WISHLIST OZONE MAG // 11 PUBLISHER/EDITOR-IN-CHIEF // Julia Beverly CHIEF OPERATIONS OFFICER // N. Ali Early MUSIC EDITOR // Randy Roper FEATURES EDITOR // Eric Perrin ART DIRECTOR // Tene Gooden ADVERTISING SALES // Che’ Johnson PROMOTIONS DIRECTOR // Malik Abdul MARKETING DIRECTOR // David Muhammad LEGAL CONSULTANT // Kyle P. King, P.A. SUBSCRIPTIONS MANAGER // Destine Cajuste ADMINISTRATIVE // Cordice Gardner, Kisha Smith CONTRIBUTORS // Alexander Cannon, Bogan, Carlton Wade, Charlamagne the God, Chuck T, E-Feezy, Edward Hall, Felita Knight, Iisha Hillmon, Jacinta Howard, Jaro Vacek, Jessica INTERVIEWS Koslow, J Lash, Jason Cordes, Jo Jo, Joey Columbo, Johnny Louis, Kamikaze, Keadron Smith, Keith Kennedy, Kenneth Brewer, K.G. -

Scratching Resources

AAFP CLAW FRIENDLY EDUCATIONAL TOOLKIT SCRATCHING RESOURCES The best method to advance feline welfare is through education. Many cat caregivers are unaware that scratching is a natu- ral behavior for cats. The AAFP has created the educational resources below to assist your team in educating cat caregivers about why cats need to scratch, ideal scratching surfaces, troubleshooting inappropriate scratching, training cats to scratch appropriately in the home, and alternatives to declawing. Veterinary Professionals Claw Counseling: Helping Clients Live Alongside Cats with Claws (In-depth Article) This comprehensive article provides more detailed information to help you counsel clients on why and how to live with a clawed cat. It provides information about why clients declaw, short and long-term complications, what causes cats to scratch excessively and on unfavorable locations, and how to work through inappropriate scratching situations. See next 7 pages for full size print version. American Association of Feline Practitioners Claw Friendly Educational Toolkit CLAW COUNSELING: Helping clients live alongside cats with claws Submitted by Kelly A. St. Denis, MSc, DVM, DABVP (feline practice) Onychectomy has always been a controversial topic, but over offers onychectomy, open dialogue about this is strongly the last decade, a large push to end this practice has been encouraged. Team members should be mindful that these brought forward by many groups, including major veterinary discussions should be approached with care and respect, for organizations, such as the American Association of Feline themselves and their employer. It is also extremely important Practitioners. As veterinary professionals, we may be asked to include front offce staff in these discussions, as they may about declawing, nail care, and normal scratching behavior in receive direct questions by phone. -

The Mixtape: a Case Study in Emancipatory Journalism

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: THE MIXTAPE: A CASE STUDY IN EMANCIPATORY JOURNALISM Jared A. Ball, Doctor of Philosophy, 2005 Directed By: Dr. Katherine McAdams Associate Professor Philip Merrill College of Journalism Associate Dean, Undergraduate Studies During the 1970s the rap music mixtape developed alongside hip-hop as an underground method of mass communication. Initially created by disc-jockeys in an era prior to popular “urban” radio and video formats, these mixtapes represented an alternative, circumventing traditional mass medium. However, as hip-hop has come under increasing corporate control within a larger consolidated media ownership environment, so too has the mixtape had to face the challenge of maintaining its autonomy. This media ownership consolidation, vertically and horizontally integrated, has facilitated further colonial control over African America and has exposed as myth notions of democratizing media in an undemocratic society. Acknowledging a colonial relationship the writer created FreeMix Radio: The Original Mixtape Radio Show where the mixtape becomes both a source of free cultural expression and an anti-colonial emancipatory journalism developed as a “Third World” response to the needs of postcolonial nation-building. This dissertation explores the contemporary colonizing effects of media consolidation, cultural industry function, and copyright ownership, concluding that the development of an underground press that recognizes the tremendous disparities in advanced technological access (the “digital divide”) appears to be the only viable alternative. The potential of the mixtape to serve as a source of emancipatory journalism is studied via a three-pronged methodological approach: 1) An explication of literature and theory related to the history of and contemporary need for resistance media, 2) an analysis of the mixtape as a potential underground mass press and 3) three focus group reactions to the mixtape as resistance media, specifically, the case study of the writer’s own FreeMix Radio: The Original Mixtape Radio Show. -

1 "Disco Madness: Walter Gibbons and the Legacy of Turntablism and Remixology" Tim Lawrence Journal of Popular Music S

"Disco Madness: Walter Gibbons and the Legacy of Turntablism and Remixology" Tim Lawrence Journal of Popular Music Studies, 20, 3, 2008, 276-329 This story begins with a skinny white DJ mixing between the breaks of obscure Motown records with the ambidextrous intensity of an octopus on speed. It closes with the same man, debilitated and virtually blind, fumbling for gospel records as he spins up eternal hope in a fading dusk. In between Walter Gibbons worked as a cutting-edge discotheque DJ and remixer who, thanks to his pioneering reel-to-reel edits and contribution to the development of the twelve-inch single, revealed the immanent synergy that ran between the dance floor, the DJ booth and the recording studio. Gibbons started to mix between the breaks of disco and funk records around the same time DJ Kool Herc began to test the technique in the Bronx, and the disco spinner was as technically precise as Grandmaster Flash, even if the spinners directed their deft handiwork to differing ends. It would make sense, then, for Gibbons to be considered alongside these and other towering figures in the pantheon of turntablism, but he died in virtual anonymity in 1994, and his groundbreaking contribution to the intersecting arts of DJing and remixology has yet to register beyond disco aficionados.1 There is nothing mysterious about Gibbons's low profile. First, he operated in a culture that has been ridiculed and reviled since the "disco sucks" backlash peaked with the symbolic detonation of 40,000 disco records in the summer of 1979. -

Indicators of Drug Or Alcohol Abuse Or Misuse

New Trends in Substance Abuse 2018 Lynn Riemer Ron Holmes, MD 720-480-0291 720-630-5430 [email protected] [email protected] www.actondrugs.org Facebook/ACTonDrugs Indicators of Drug or Alcohol Abuse or Misuse: Behavioral Physical - Abnormal behavior - Breath or body odor - Exaggerated behavior - Lack of coordination - Boisterous or argumentative - Uncoordinated & unsteady gait - Withdrawn - Unnecessary use of arms or supports for balance - Avoidance - Sweating and/or dry mouth - Changing emotions & erratic behavior - Change in appearance Speech Performance - Slurred or slow speech - Inability to concentrate - Nonsensical patterns - Fatigue & lack of motivation - Confusion - Slowed reactions - Impaired driving ability The physiologic factors predisposing to addiction Nearly every addictive drug targets the brain’s reward system by flooding the circuit with the neurotransmitter, dopamine. Neurotransmitters are necessary to transfer impulses from one brain cell to another. The brain adapts to the overwhelming surges in dopamine by ultimately producing less dopamine and by reducing the number of dopamine receptors in the reward circuit. As a result, two important physiologic adaptations occur: (1) the addict’s ability to enjoy the things that previously brought pleasure is impaired because of decreased dopamine, and (2) higher and higher doses of the abused drug are needed to achieve the same “high” that occurred when the drug was first used. This compels the addict to increase drug consumption to increase dopamine production leading to physiologic addiction with more and more intense cravings for the drug. The effects of addiction on the brain Nearly all substances of abuse affect the activity of neurotransmitters that play an important role in connecting one brain cell to another. -

Confessions of a Black Female Rapper: an Autoethnographic Study on Navigating Selfhood and the Music Industry

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University African-American Studies Theses Department of African-American Studies 5-8-2020 Confessions Of A Black Female Rapper: An Autoethnographic Study On Navigating Selfhood And The Music Industry Chinwe Salisa Maponya-Cook Georgia State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/aas_theses Recommended Citation Maponya-Cook, Chinwe Salisa, "Confessions Of A Black Female Rapper: An Autoethnographic Study On Navigating Selfhood And The Music Industry." Thesis, Georgia State University, 2020. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/aas_theses/66 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of African-American Studies at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in African-American Studies Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CONFESSIONS OF A BLACK FEMALE RAPPER: AN AUTOETHNOGRAPHIC STUDY ON NAVIGATING SELFHOOD AND THE MUSIC INDUSTRY by CHINWE MAPONYA-COOK Under the DireCtion of Jonathan Gayles, PhD ABSTRACT The following research explores the ways in whiCh a BlaCk female rapper navigates her selfhood and traditional expeCtations of the musiC industry. By examining four overarching themes in the literature review - Hip-Hop, raCe, gender and agency - the author used observations of prominent BlaCk female rappers spanning over five deCades, as well as personal experiences, to detail an autoethnographiC aCCount of self-development alongside pursuing a musiC career. MethodologiCally, the author wrote journal entries to detail her experiences, as well as wrote and performed an aCCompanying original mixtape entitled The Thesis (available on all streaming platforms), as a creative addition to the research.