26 in the Mid-1980'S, Noise Music Seemed to Be Everywhere Crossing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sonic Necessity-Exarchos

Sonic Necessity and Compositional Invention in #BluesHop: Composing the Blues for Sample-Based Hip Hop Abstract Rap, the musical element of Hip-Hop culture, has depended upon the recorded past to shape its birth, present and, potentially, its future. Founded upon a sample-based methodology, the style’s perceived authenticity and sonic impact are largely attributed to the use of phonographic records, and the unique conditions offered by composition within a sampling context. Yet, while the dependence on pre-existing recordings challenges traditional notions of authorship, it also results in unavoidable legal and financial implications for sampling composers who, increasingly, seek alternative ways to infuse the sample-based method with authentic content. But what are the challenges inherent in attempting to compose new material—inspired by traditional forms—while adhering to Rap’s unique sonic rationale, aesthetics and methodology? How does composing within a stylistic frame rooted in the past (i.e. the Blues) differ under the pursuit of contemporary sonics and methodological preferences (i.e. Hip-Hop’s sample-based process)? And what are the dynamics of this inter-stylistic synthesis? The article argues that in pursuing specific, stylistically determined sonic objectives, sample-based production facilitates an interactive typology of unique conditions for the composition, appropriation, and divergence of traditional musical forms, incubating era-defying genres that leverage the dynamics of this interaction. The musicological inquiry utilizes (auto)ethnography reflecting on professional creative practice, in order to investigate compositional problematics specific to the applied Blues-Hop context, theorize on the nature of inter- stylistic composition, and consider the effects of electronic mediation on genre transformation and stylistic morphing. -

DJ Skills the Rise of the Hip-Hop DJ 3

The Rise of the Hip-Hop DJ 1 74 The Rise of The Hip-hop DJ DJs were Hip-hop’s original architects, and remain crucial to its contin- ued development. Hip-hop is more than a style of music; it’s a culture. As with any culture, there are various artistic expressions of Hip-hop, the four principal expressions being: • visual art (graffiti) • dance (breaking, rocking, locking, and popping, collectively known in the media as “break dancing”) • literature (rap lyrics and slam poetry) • music (DJing and turntablism) Unlike the European Renaissance or the Ming Dynasty, Hip-hop is a culture that is very much alive and still evolving. Some argue that Hip-hop is the most influential cultural movement in history, point- ing to the globalization of Hip-hop music, fashion, and other forms of expression. Style has always been at the forefront of Hip-hop. Improvisation is called free styling, whether in rap, turntablism, breaking, or graf- fiti writing. Since everyone is using the essentially same tools (spray paint for graffiti writers, microphones for rappers and beat boxers, their bodies for dancers, and two turntables with a mixer for DJs), it’s the artists’ personal styles that set them apart. It’s no coincidence that two of the most authentic movies about the genesis of the move- ment are titled Wild Style and Style Wars. There are also many styles of writing the word “Hip-hop.” The mainstream media most often oscillates between “hip-hop” and “hip hop.” The Hiphop Archive at Harvard writes “Hiphop” as one word, 2 DJ Skills The Rise of the Hip-Hop DJ 3 with a capital H, embracing KRS-ONE’s line of reasoning that “Hiphop Kool DJ Herc is a culture with its own foundation narrative, history, natives, and 7 In 1955 in Jamaica, a young woman from the parish of Saint Mary mission.” After a great deal of input from many people in the Hip-hop community, I’ve decided to capitalize the word but keep the hyphen, gave birth to a son who would become the father of Hip-hop. -

Turntablism and Audio Art Study 2009

TURNTABLISM AND AUDIO ART STUDY 2009 May 2009 Radio Policy Broadcasting Directorate CRTC Catalogue No. BC92-71/2009E-PDF ISBN # 978-1-100-13186-3 Contents SUMMARY 1 HISTORY 1.1-Defintion: Turntablism 1.2-A Brief History of DJ Mixing 1.3-Evolution to Turntablism 1.4-Definition: Audio Art 1.5-Continuum: Overlapping definitions for DJs, Turntablists, and Audio Artists 1.6-Popularity of Turntablism and Audio Art 2 BACKGROUND: Campus Radio Policy Reviews, 1999-2000 3 SURVEY 2008 3.1-Method 3.2-Results: Patterns/Trends 3.3-Examples: Pre-recorded music 3.4-Examples: Live performance 4 SCOPE OF THE PROBLEM 4.1-Difficulty with using MAPL System to determine Canadian status 4.2- Canadian Content Regulations and turntablism/audio art CONCLUSION SUMMARY Turntablism and audio art are becoming more common forms of expression on community and campus stations. Turntablism refers to the use of turntables as musical instruments, essentially to alter and manipulate the sound of recorded music. Audio art refers to the arrangement of excerpts of musical selections, fragments of recorded speech, and ‘found sounds’ in unusual and original ways. The following paper outlines past and current difficulties in regulating these newer genres of music. It reports on an examination of programs from 22 community and campus stations across Canada. Given the abstract, experimental, and diverse nature of these programs, it may be difficult to incorporate them into the CRTC’s current music categories and the current MAPL system for Canadian Content. Nonetheless, turntablism and audio art reflect the diversity of Canada’s artistic community. -

1 "Disco Madness: Walter Gibbons and the Legacy of Turntablism and Remixology" Tim Lawrence Journal of Popular Music S

"Disco Madness: Walter Gibbons and the Legacy of Turntablism and Remixology" Tim Lawrence Journal of Popular Music Studies, 20, 3, 2008, 276-329 This story begins with a skinny white DJ mixing between the breaks of obscure Motown records with the ambidextrous intensity of an octopus on speed. It closes with the same man, debilitated and virtually blind, fumbling for gospel records as he spins up eternal hope in a fading dusk. In between Walter Gibbons worked as a cutting-edge discotheque DJ and remixer who, thanks to his pioneering reel-to-reel edits and contribution to the development of the twelve-inch single, revealed the immanent synergy that ran between the dance floor, the DJ booth and the recording studio. Gibbons started to mix between the breaks of disco and funk records around the same time DJ Kool Herc began to test the technique in the Bronx, and the disco spinner was as technically precise as Grandmaster Flash, even if the spinners directed their deft handiwork to differing ends. It would make sense, then, for Gibbons to be considered alongside these and other towering figures in the pantheon of turntablism, but he died in virtual anonymity in 1994, and his groundbreaking contribution to the intersecting arts of DJing and remixology has yet to register beyond disco aficionados.1 There is nothing mysterious about Gibbons's low profile. First, he operated in a culture that has been ridiculed and reviled since the "disco sucks" backlash peaked with the symbolic detonation of 40,000 disco records in the summer of 1979. -

Sooloos Collections: Advanced Guide

Sooloos Collections: Advanced Guide Sooloos Collectiions: Advanced Guide Contents Introduction ...........................................................................................................................................................3 Organising and Using a Sooloos Collection ...........................................................................................................4 Working with Sets ..................................................................................................................................................5 Organising through Naming ..................................................................................................................................7 Album Detail ....................................................................................................................................................... 11 Finding Content .................................................................................................................................................. 12 Explore ............................................................................................................................................................ 12 Search ............................................................................................................................................................. 14 Focus .............................................................................................................................................................. -

Clever Children: the Sons and Daughters of Experimental Music?

Clever Children: The Sons and Daughters of Experimental Music Author Carter, David Published 2009 Thesis Type Thesis (PhD Doctorate) School Queensland Conservatorium DOI https://doi.org/10.25904/1912/1356 Copyright Statement The author owns the copyright in this thesis, unless stated otherwise. Downloaded from http://hdl.handle.net/10072/367632 Griffith Research Online https://research-repository.griffith.edu.au Clever Children: The Sons and Daughters of Experimental Music? David Carter B.Music / Music Technology (Honours, First Class) Queensland Conservatorium Griffith University A dissertation submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the degree Doctor of Philosophy 19 June 2008 Keywords Contemporary Music; Dance Music; Disco; DJ; DJ Spooky; Dub; Eight Lines; Electronica; Electronic Music; Errata Erratum; Experimental Music; Hip Hop; House; IDM; Influence; Techno; John Cage; Minimalism; Music History; Musicology; Rave; Reich Remixed; Scanner; Surface Noise. i Abstract In the late 1990s critics, journalists and music scholars began referring to a loosely associated group of artists within Electronica who, it was claimed, represented a new breed of experimentalism predicated on the work of composers such as John Cage, Karlheinz Stockhausen and Steve Reich. Though anecdotal evidence exists, such claims by, or about, these ‘Clever Children’ have not been adequately substantiated and are indicative of a loss of history in relation to electronic music forms (referred to hereafter as Electronica) in popular culture. With the emergence of the Clever Children there is a pressing need to redress this loss of history through academic scholarship that seeks to document and critically reflect on the rhizomatic developments of Electronica and its place within the history of twentieth century music. -

Communication Design Quarterly

Online First 2018 Communication Design Quarterly Published by the Association for ComputingVolume Machinery 1 Issue 1 Special Interest Group for Design of CommunicationJanuary 2012 ISSN: 2166-1642 DJs, Playlists, and Community: Imagining Communication Design through Hip Hop Victor Del Hierro University of Texas at El Paso [email protected] Published Online October 17, 2018 CDQ 10.1145/3274995.3274997 This article will be compiled into the quarterly publication and archived in the ACM Digital Library. Communication Design Quarterly, Online First https://sigdoc.acm.org/publication/ DJs, Playlists, and Community: Imagining Communication Design through Hip Hop Victor Del Hierro University of Texas at El Paso [email protected] ABSTRACT INTRODUCTION This article argues for the inclusion of Hip Hop communities in Recent work in Technical/Professional Communication has made technical communication research. Through Hip Hop, technical calls for expanding the field by turning to social justice through communicators can address the recent call for TPC work to expand culturally sensitive and diverse studies that honor communities the field through culturally sensitive and diverse studies that honor and their practices (Agboka, 2013; Haas, 2012; Maylath et communities and their practices. Using a Hip Hop community al., 2013). While this work pushes our field toward important in Houston as a case study, this article discusses the way DJs ethical responsibilities, it also helps build rigorous research operate as technical communicators within their communities. and methods that help meet the needs of already globalized and Furthermore, Hip Hop DJs build complex relationships with complex communication praxis (Walton, Zraly, & Mugengana, communities to create localized and accessible content. -

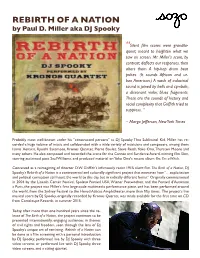

REBIRTH of a NATION by Paul D

REBIRTH OF A NATION by Paul D. Miller aka DJ Spooky “Silent film scores were grandilo- quent, meant to heighten what we saw on screen. Mr. Miller's score, by contrast, deflects our responses, then alters them. A hip-hop drum beat pulses. (It sounds African and ur- ban American.) A wash of industrial sound is joined by bells and cymbals; a dissonant violin; blues fragments. These are the sounds of history and racial complexity that Griffith tried to suppress. ” – Margo Jefferson, New York Times Probably most well-known under his "constructed persona" as DJ Spooky That Subliminal Kid, Miller has re- corded a huge volume of music and collaborated with a wide variety of musicians and composers, among them Iannis Xenakis, Ryuichi Sakamoto, Kronos Quartet, Pierre Boulez, Steve Reich, Yoko Ono, Thurston Moore and many others. He also composed and recorded the score for the Cannes and Sundance Award-winning filmSlam , starring acclaimed poet Saul Williams, and produced material on Yoko Ono's recent album Yes, I'm a Witch. Conceived as a reimagining of director D.W. Griffith’s infamously racist 1915 silent film The Birth of a Nation, DJ Spooky’s Rebirth of a Nation is a controversial and culturally significant project that examines how “…exploitation and political corruption still haunt the world to this day, but in radically different forms.” Originally commissioned in 2004 by the Lincoln Center Festival, Spoleto Festival USA, Wiener Festwochen, and the Festival d'Automne a Paris, the project was Miller’s first large-scale multimedia performance piece, and has been performed around the world, from the Sydney Festival to the Herod Atticus Amphitheater, more than fifty times. -

Dancehall, Rap, Reggaeton: Beats, Rhymes, and Routes Indicate If Seminar And/Or Writing II Course

Music History 79 General Education Course Information Sheet Please submit this sheet for each proposed course Department & Course Number MUS HST 79 Course Title Dancehall, Rap, Reggaeton: Beats, Rhymes, and Routes Indicate if Seminar and/or Writing II course 1 Check the recommended GE foundation area(s) and subgroups(s) for this course Foundations of the Arts and Humanities • Literary and Cultural Analysis • Philosophic and Linguistic Analysis • Visual and Performance Arts Analysis and Practice x Foundations of Society and Culture • Historical Analysis • Social Analysis Foundations of Scientific Inquiry • Physical Science With Laboratory or Demonstration Component must be 5 units (or more) • Life Science With Laboratory or Demonstration Component must be 5 units (or more) 2. Briefly describe the rationale for assignment to foundation area(s) and subgroup(s) chosen. The course will analyze the history, aesthetics, and social relevance of the following musical genres: dancehall, rap, and reggaeton. In addition, it will introduce students to a variety of related musical genres and increase their ability to hear differences among styles of popular music and to interpret the meanings of such differences. 3. "List faculty member(s) who will serve as instructor (give academic rank): Jerome Camal, Visiting Assistant Professor Do you intend to use graduate student instructors (TAs) in this course? Yes x No If yes, please indicate the number of TAs 2 4. Indicate when do you anticipate teaching this course over the next three years: 2010-2011 Fall Winter Spring Enrollment Enrollment Enrollment 2011-2012 Fall Winter Spring x Enrollment Enrollment Enrollment 120 2012-2013 Fall Winter Spring Enrollment Enrollment Enrollment 5. -

Paul D. Miller, Aka DJ Spooky That Subliminal Kid: Ice Music (CAE1217)

Paul D. Miller, aka DJ Spooky that Subliminal Kid: Ice Music Collection CAE1217 Introduction/Abstract For his book and exhibition titled Ice Music, Miller worked through music, photographs and film stills from his journeys to the Antarctic and Arctic, along with original artworks, and re-appropriated archival materials, to contemplate humanity’s relationship with the natural world. Materials include graphics from The Books of Ice, copies of four original scores composed by Paul Miller, DVD of Syfy Channel clips, the CD Ice Music, press, photographs, and pieces of personal gear used in the Polar Regions. Biographical Note: Paul D. Miller Paul D. Miller, also known as ‘DJ Spooky, That Subliminal Kid’, which is his stage name and self constructed persona, is an experimental and electronic hip-hop musician, conceptual artist, and writer. He was born in 1970 in Washington DC but has been based in New York City for many years. He is the son of one of Howard University's former Deans of Law who died when he was only three, and a mother who was in charge of a fabric shop of international repute. Paul Miller then spent the main part of his childhood in Washington DC’s nurturing bohemia. Paul Miller is a Professor at the European Graduate School (EGS) where he teaches Music Mediated Art. DJ Spooky is known amongst other things for his electronic experimentations in music known as both “illbient” and “trip hop.” His first album, Dead Dreamer, was released in 1996 and he has since then released over a dozen albums. Miller, as DJ Spooky, has collaborated with drummer Dave Lombardo of thrash metal band Slayer; singer, songwriter and guitarist Thurston Moore of Sonic Youth; Chuck D of Public Enemy fame; rapper Kool Keith; Towa Tei, formerly of Deee-Lite; Vernon Reid of Living Colour; The Coup; artists Yoko Ono and Shepard Fairey and many others. -

Text-Based Description of Music for Indexing, Retrieval, and Browsing

JOHANNES KEPLER UNIVERSITAT¨ LINZ JKU Technisch-Naturwissenschaftliche Fakult¨at Text-Based Description of Music for Indexing, Retrieval, and Browsing DISSERTATION zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades Doktor im Doktoratsstudium der Technischen Wissenschaften Eingereicht von: Dipl.-Ing. Peter Knees Angefertigt am: Institut f¨ur Computational Perception Beurteilung: Univ.Prof. Dipl.-Ing. Dr. Gerhard Widmer (Betreuung) Ao.Univ.Prof. Dipl.-Ing. Dr. Andreas Rauber Linz, November 2010 ii Eidesstattliche Erkl¨arung Ich erkl¨are an Eides statt, dass ich die vorliegende Dissertation selbstst¨andig und ohne fremde Hilfe verfasst, andere als die angegebenen Quellen und Hilfsmittel nicht benutzt bzw. die w¨ortlich oder sinngem¨aß entnommenen Stellen als solche kenntlich gemacht habe. iii iv Kurzfassung Ziel der vorliegenden Dissertation ist die Entwicklung automatischer Methoden zur Extraktion von Deskriptoren aus dem Web, die mit Musikst¨ucken assoziiert wer- den k¨onnen. Die so gewonnenen Musikdeskriptoren erlauben die Indizierung um- fassender Musiksammlungen mithilfe vielf¨altiger Bezeichnungen und erm¨oglichen es, Musikst¨ucke auffindbar zu machen und Sammlungen zu explorieren. Die vorgestell- ten Techniken bedienen sich g¨angiger Web-Suchmaschinen um Texte zu finden, die in Beziehung zu den St¨ucken stehen. Aus diesen Texten werden Deskriptoren gewon- nen, die zum Einsatz kommen k¨onnen zur Beschriftung, um die Orientierung innerhalb von Musikinterfaces zu ver- • einfachen (speziell in einem ebenfalls vorgestellten dreidimensionalen Musik- interface), als Indizierungsschlagworte, die in Folge als Features in Retrieval-Systemen f¨ur • Musik dienen, die Abfragen bestehend aus beliebigem, beschreibendem Text verarbeiten k¨onnen, oder als Features in adaptiven Retrieval-Systemen, die versuchen, zielgerichtete • Vorschl¨age basierend auf dem Suchverhalten des Benutzers zu machen. -

The Future Is History: Hip-Hop in the Aftermath of (Post)Modernity

The Future is History: Hip-hop in the Aftermath of (Post)Modernity Russell A. Potter Rhode Island College From The Resisting Muse: Popular Music and Social Protest, edited by Ian Peddie (Aldershot, Hampshire: Ashgate Publishing, 2006). When hip-hop first broke in on the (academic) scene, it was widely hailed as a boldly irreverent embodiment of the postmodern aesthetics of pastiche, a cut-up method which would slice and dice all those old humanistic truisms which, for some reason, seemed to be gathering strength again as the end of the millennium approached. Today, over a decade after the first academic treatments of hip-hop, both the intellectual sheen of postmodernism and the counter-cultural patina of hip-hip seem a bit tarnished, their glimmerings of resistance swallowed whole by the same ubiquitous culture industry which took the rebellion out of rock 'n' roll and locked it away in an I.M. Pei pyramid. There are hazards in being a young art form, always striving for recognition even while rejecting it Ice Cube's famous phrase ‘Fuck the Grammys’ comes to mind but there are still deeper perils in becoming the single most popular form of music in the world, with a media profile that would make even Rupert Murdoch jealous. In an era when pioneers such as KRS-One, Ice-T, and Chuck D are well over forty and hip-hop ditties about thongs and bling bling dominate the malls and airwaves, it's noticeably harder to locate any points of friction between the microphone commandos and the bourgeois masses they once seemed to terrorize with sonic booms pumping out of speaker-loaded jeeps.