The Riddim Method: Aesthetics, Practice, and Ownership in Jamaican Dancehall1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In Defense of Rap Music: Not Just Beats, Rhymes, Sex, and Violence

In Defense of Rap Music: Not Just Beats, Rhymes, Sex, and Violence THESIS Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Master of Arts Degree in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Crystal Joesell Radford, BA Graduate Program in Education The Ohio State University 2011 Thesis Committee: Professor Beverly Gordon, Advisor Professor Adrienne Dixson Copyrighted by Crystal Joesell Radford 2011 Abstract This study critically analyzes rap through an interdisciplinary framework. The study explains rap‟s socio-cultural history and it examines the multi-generational, classed, racialized, and gendered identities in rap. Rap music grew out of hip-hop culture, which has – in part – earned it a garnering of criticism of being too “violent,” “sexist,” and “noisy.” This criticism became especially pronounced with the emergence of the rap subgenre dubbed “gangsta rap” in the 1990s, which is particularly known for its sexist and violent content. Rap music, which captures the spirit of hip-hop culture, evolved in American inner cities in the early 1970s in the South Bronx at the wake of the Civil Rights, Black Nationalist, and Women‟s Liberation movements during a new technological revolution. During the 1970s and 80s, a series of sociopolitical conscious raps were launched, as young people of color found a cathartic means of expression by which to describe the conditions of the inner-city – a space largely constructed by those in power. Rap thrived under poverty, police repression, social policy, class, and gender relations (Baker, 1993; Boyd, 1997; Keyes, 2000, 2002; Perkins, 1996; Potter, 1995; Rose, 1994, 2008; Watkins, 1998). -

Curt Magazin N/F/E

curt Magazin N/F/E #158 - - - OKTOBER 2011 - - - WWW.CURT.DE Vorwort / curt #158 Ich löse vier Aspirin und zwei Alka-Seltzer in meiner Maß Bier auf, da mir das rechte Ohr pfeift. Eigendiagnose: Tinitus. Tinitus durch Ärger mit den curt-Schreiberlingen. Dabei war es von Anfang an klar: Die Besten sind eben auch immer Exzentriker. Dass mich das krank machen NEUERNEUERNEUERNEUER JOB JOBJOB JOB GEFÄLLIG? GEFÄLLIG?GEFÄLLIG? GEFÄLLIG? könnte und von einem Burn-out in den nächsten treiben würde, daran hatte ich nie gedacht. Und: Keine Besserung in Sicht. Dabei führen sie doch ein Leben in Saus und Braus hoch zehn, die curt-Recken. Denn natürlich ist es nicht unangenehm, in Cannes am richtigen Wochenende nur mit einem güldenen String bekleidet und mit einem Starlet im Arm von der Yacht herab ins Blitzlichtgewitter zu schreiten. Oder bei den MTV Awards lasziv von Gwen Stefanie begrapscht zu werden. Auch die richtige Party nach den Oscar-Verleihungen hat was, oder das Abhängen in Boxengassen. Und ebenfalls okay: die eine oder andere Filmpremiere oder Vernissage (Tach, Neo! Servus, Damien!). „Wie kann sich ein curt-Redakteur das alles leisten?“, wird sich ein Naivling jetzt fragen. Haha, Du ahnungsloser Narr! Du unwis- sender Konsument! Das kostet NISCHT! NULLINGER! Wir sind geladene Gäste im Schlaraffenland, so sieht's aus. Der Firmen-Porsche? Ein Geschenk! Der Akquise-Ferrari? Eine Spende. Der Verteiler-Hummer? Eine Leihgabe von einem Scheich, dessen Sohn wir mal zum Kopulieren NEUER JOB GEFÄLLIG? backstage gebracht haben bei der Comedy Lounge. Warum wir gerade alle in Louis Vuitton gekleidet sind? Eine Koop: Der curt-eigene Kaulquappenhund ist Model der aktuellen Kampagne. -

Jamaican Politics, Nationalism, and Musical Culture in Transition, 1974-1984

University of New Orleans ScholarWorks@UNO University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations Dissertations and Theses 5-18-2007 Between Two Giant Sounds: Jamaican Politics, Nationalism, and Musical Culture in Transition, 1974-1984 Caree Banton University of New Orleans Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td Recommended Citation Banton, Caree, "Between Two Giant Sounds: Jamaican Politics, Nationalism, and Musical Culture in Transition, 1974-1984" (2007). University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations. 508. https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td/508 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by ScholarWorks@UNO with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights- holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Between Two Giant Sounds: Jamaican Politics, Nationalism, and Musical Culture in Transition, 1974 – 1984 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the University of New Orleans In partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Master of Arts In History By Caree Ann-Marie Banton B.A. Grambling State University 2005 B.P.A Grambling State University 2005 May 2007 Acknowledgement I would like to thank all the people that facilitated the completion of this work. -

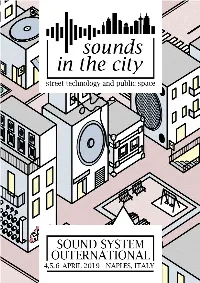

SS05 Naple Full Programme.Pdf

Across the globe the adaptation of Jamaican sound system culture has stimulated an innovative approach to sound technologies deployed to re-configure public spaces as sites for conviviality, celebration, resistance and different ways-of-knowing. In a world of digital social media, the shared, multi-sensory, social and embodied experience of the sound system session becomes ever more important and valuable. Sound System Outernational #5 – “Sounds in the City: Street Technology and Public Space” (4-5-6 April, 2019 - Naples, Italy) is designed as a multi-layered event hosted at Università degli Studi di Napoli L’Orientale with local social movement partners. Over three days and interacting with the city of Naples in its rich academic, social, political and musical dimensions, the event includes talks, roundtables, exhibitions and film screenings. It also features sound system dances hosting local and international performers in some of the city’s most iconic social spaces. The aim of the program is to provide the chance for foreign researchers to experience the local sound system scene in the grassroots venues that constitute this culture’s infrastructure in Naples. This aims to stimulate a fruitful exchange between the academic community and local practitioners, which has always been SSO’s main purpose. Sounds in the City will also provide the occasion for the SSO international research network meeting and the opportunity for a short-term research project on the Napoli sound system scene. Thursday, April 4th the warm-up session Thursday, April 4th “Warm Up Session” (16:30 to midnight) Venue: Palazzo Giusso, Università L’Orientale - Room 3.5 (Largo S. -

Sly & Robbie – Primary Wave Music

SLY & ROBBIE facebook.com/slyandrobbieofficial Imageyoutube.com/channel/UC81I2_8IDUqgCfvizIVLsUA not found or type unknown en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sly_and_Robbie open.spotify.com/artist/6jJG408jz8VayohX86nuTt Sly Dunbar (Lowell Charles Dunbar, 10 May 1952, Kingston, Jamaica, West Indies; drums) and Robbie Shakespeare (b. 27 September 1953, Kingston, Jamaica, West Indies; bass) have probably played on more reggae records than the rest of Jamaica’s many session musicians put together. The pair began working together as a team in 1975 and they quickly became Jamaica’s leading, and most distinctive, rhythm section. They have played on numerous releases, including recordings by U- Roy, Peter Tosh, Bunny Wailer, Culture and Black Uhuru, while Dunbar also made several solo albums, all of which featured Shakespeare. They have constantly sought to push back the boundaries surrounding the music with their consistently inventive work. Dunbar, nicknamed ‘Sly’ in honour of his fondness for Sly And The Family Stone, was an established figure in Skin Flesh And Bones when he met Shakespeare. Dunbar drummed his first session for Lee Perry as one of the Upsetters; the resulting ‘Night Doctor’ was a big hit both in Jamaica and the UK. He next moved to Skin Flesh And Bones, whose variations on the reggae-meets-disco/soul sound brought them a great deal of session work and a residency at Kingston’s Tit For Tat club. Sly was still searching for more, however, and he moved on to another session group in the mid-70s, the Revolutionaries. This move changed the course of reggae music through the group’s work at Joseph ‘Joe Joe’ Hookim’s Channel One Studio and their pioneering rockers sound. -

Dancehall Dossier.Cdr

DANCEHALL DOSSIER STOP M URDER MUSIC DANCEHALL DOSSIER Beenie Man Beenie Man - Han Up Deh Hang chi chi gal wid a long piece of rope Hang lesbians with a long piece of rope Beenie Man Damn I'm dreaming of a new Jamaica, come to execute all the gays I'm dreaming of a new Jamaica, come to execute all the gays Beenie Man Beenie Man - Batty Man Fi Dead Real Name: Anthony M Davis (aka ‘Weh U No Fi Do’) Date of Birth: 22 August 1973 (Queers Must Be killed) All batty man fi dead! Jamaican dancehall-reggae star Beenie All faggots must be killed! Man has personally denied he had ever From you fuck batty den a coppa and lead apologised for his “kill gays” music and, to If you fuck arse, then you get copper and lead [bullets] prove it, performed songs inciting the murder of lesbian and gay people. Nuh man nuh fi have a another man in a him bed. No man must have another man in his bed In two separate articles, The Jamaica Observer newspaper revealed Beenie Man's disavowal of his apology at the Red Beenie Man - Roll Deep Stripe Summer Sizzle concert at James Roll deep motherfucka, kill pussy-sucker Bond Beach, Jamaica, on Sunday 22 August 2004. Roll deep motherfucker, kill pussy-sucker Pussy-sucker:a lesbian, or anyone who performs cunnilingus. “Beenie Man, who was celebrating his Tek a Bazooka and kill batty-fucker birthday, took time to point out that he did not apologise for his gay-bashing lyrics, Take a bazooka and kill bum-fuckers [gay men] and went on to perform some of his anti- gay tunes before delving into his popular hits,” wrote the Jamaica Observer QUICK FACTS “He delivered an explosive set during which he performed some of the singles that have drawn the ire of the international Virgin Records issued an apology on behalf Beenie Man but within gay community,” said the Observer. -

Barrington Levy Living Dangerously Mp3, Flac, Wma

Barrington Levy Living Dangerously mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Reggae Album: Living Dangerously Country: Jamaica Released: 1995 Style: Reggae, Dub, Ragga MP3 version RAR size: 1500 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1808 mb WMA version RAR size: 1510 mb Rating: 4.6 Votes: 884 Other Formats: MPC MIDI VOX MP2 WMA XM MP1 Tracklist A –Barrington Levy / Bounty Killa* Living Dangerously B –Jah Screw Living Dangerously (Version) Credits Producer – Jah Screw Notes Distributed by Sonic Sounds. Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year Barrington Levy / Barrington Levy Time 1 none Bounti Killer* - Living none Jamaica 1995 / Bounti Killer* International Dangerously (7") Barrington Levy / Barrington Levy RAS 7062 Bounty Killer - Living RAS Records RAS 7062 US 1995 / Bounty Killer Dangerously (12") Barrington Levy & Barrington Levy Bounty Killer - Living Time 1 none none Jamaica 1995 & Bounty Killer Dangerously (7", MP, International RP) Barrington Levy & Barrington Levy Time 1 none Bounty Killer - Living none Jamaica Unknown & Bounty Killer International Dangerously (7", RP) Barrington Levy / Barrington Levy Time 1 none Bounty Killer - Living none Jamaica 1996 / Bounty Killer International Dangerously (7") Related Music albums to Living Dangerously by Barrington Levy Barrington Levy - Bad Talk Barrington Levy - Under The Sensi Barrington Levy & Ce'cile - My Woman Barrington Levy & Josey Wales - Pick Your Choice Barrington Levy - Don't Throw It All Away Barrington Levy - A Blessing From Above Barrington Levy & Beenie Man - Under Mi Sensi Slaughter & Barrington Levy - Ragga Muffin Time Barrington Levy & Gregory Peck - Here I Come Barrington Levy - English Man Barrington Levy - Struggler Barrington Levy - Under Mi Sensi. -

Jah Stitch, Pioneering Reggae Vocalist, Dies Aged 69

‘Original raggamuffin’ Jah Stitch, pioneering reggae vocalist, dies aged 69 Sound system toaster, DJ and selector, known for his understated delivery and immaculate dress died in Kingston David Katz Thu 2 May 2019 15.03 BSTLast modified on Fri 3 May 2019 09.47 BST FROM: https://www.theguardian.com/music/2019/may/02/original-raggamu ffin-jah-stitch-pioneering-reggae-vocalist-dies-aged-69 Jah Stitch on Princess Street, downtown Kingston in 2011. Photograph: Mark Read The Jamaican reggae vocalist Jah Stitch died in Kingston on Sunday aged 69, following a brief illness. Although not necessarily a household name abroad, the “original raggamuffin” was a sound system toaster and DJ who scored significant hits in the 70s, later working as an actor and appearing in an ad campaign for Clarks shoes. Born Melbourne James in Kingston in 1949, he grew up with an aunt in a rural village in St Mary, northern Jamaica, since his teenage mother lacked the financial means to care for him. He later joined her in bustling Papine, east Kingston, but conflict with his father-in-law led him to join a community of outcasts living in a tenement yard in the heart of the capital’s downtown – territory aligned with the People’s National party and controlled by the notorious Spanglers gang, which James became affiliated with aged 11. As ska and rock steady gave way to the new reggae style on the nascent Kingston music scene, young James became a regular fixture of sound system dances. He drew his biggest inspiration from the Studio One selections presented by Prince Rough on Sir George the Atomic, based in Jones Town, and the microphone skills of Dennis Alcapone on El Paso, based further west at Waltham Park Road. -

The Mixtape: a Case Study in Emancipatory Journalism

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: THE MIXTAPE: A CASE STUDY IN EMANCIPATORY JOURNALISM Jared A. Ball, Doctor of Philosophy, 2005 Directed By: Dr. Katherine McAdams Associate Professor Philip Merrill College of Journalism Associate Dean, Undergraduate Studies During the 1970s the rap music mixtape developed alongside hip-hop as an underground method of mass communication. Initially created by disc-jockeys in an era prior to popular “urban” radio and video formats, these mixtapes represented an alternative, circumventing traditional mass medium. However, as hip-hop has come under increasing corporate control within a larger consolidated media ownership environment, so too has the mixtape had to face the challenge of maintaining its autonomy. This media ownership consolidation, vertically and horizontally integrated, has facilitated further colonial control over African America and has exposed as myth notions of democratizing media in an undemocratic society. Acknowledging a colonial relationship the writer created FreeMix Radio: The Original Mixtape Radio Show where the mixtape becomes both a source of free cultural expression and an anti-colonial emancipatory journalism developed as a “Third World” response to the needs of postcolonial nation-building. This dissertation explores the contemporary colonizing effects of media consolidation, cultural industry function, and copyright ownership, concluding that the development of an underground press that recognizes the tremendous disparities in advanced technological access (the “digital divide”) appears to be the only viable alternative. The potential of the mixtape to serve as a source of emancipatory journalism is studied via a three-pronged methodological approach: 1) An explication of literature and theory related to the history of and contemporary need for resistance media, 2) an analysis of the mixtape as a potential underground mass press and 3) three focus group reactions to the mixtape as resistance media, specifically, the case study of the writer’s own FreeMix Radio: The Original Mixtape Radio Show. -

Confessions of a Black Female Rapper: an Autoethnographic Study on Navigating Selfhood and the Music Industry

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University African-American Studies Theses Department of African-American Studies 5-8-2020 Confessions Of A Black Female Rapper: An Autoethnographic Study On Navigating Selfhood And The Music Industry Chinwe Salisa Maponya-Cook Georgia State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/aas_theses Recommended Citation Maponya-Cook, Chinwe Salisa, "Confessions Of A Black Female Rapper: An Autoethnographic Study On Navigating Selfhood And The Music Industry." Thesis, Georgia State University, 2020. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/aas_theses/66 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of African-American Studies at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in African-American Studies Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CONFESSIONS OF A BLACK FEMALE RAPPER: AN AUTOETHNOGRAPHIC STUDY ON NAVIGATING SELFHOOD AND THE MUSIC INDUSTRY by CHINWE MAPONYA-COOK Under the DireCtion of Jonathan Gayles, PhD ABSTRACT The following research explores the ways in whiCh a BlaCk female rapper navigates her selfhood and traditional expeCtations of the musiC industry. By examining four overarching themes in the literature review - Hip-Hop, raCe, gender and agency - the author used observations of prominent BlaCk female rappers spanning over five deCades, as well as personal experiences, to detail an autoethnographiC aCCount of self-development alongside pursuing a musiC career. MethodologiCally, the author wrote journal entries to detail her experiences, as well as wrote and performed an aCCompanying original mixtape entitled The Thesis (available on all streaming platforms), as a creative addition to the research. -

WXYC Brings You Gems from the Treasure of UNC's Southern

IN/AUDIBLE LETTER FROM THE EDITOR a publication of N/AUDIBLE is the irregular newsletter of WXYC – your favorite Chapel Hill radio WXYC 89.3 FM station that broadcasts 24 hours a day, seven days a week out of the Student Union on the UNC campus. The last time this publication came out in 2002, WXYC was CB 5210 Carolina Union Icelebrating its 25th year of existence as the student-run radio station at the University of Chapel Hill, NC 27599 North Carolina at Chapel Hill. This year we celebrate another big event – our tenth anni- USA versary as the first radio station in the world to simulcast our signal over the Internet. As we celebrate this exciting event and reflect on the ingenuity of a few gifted people who took (919) 962-7768 local radio to the next level and beyond Chapel Hill, we can wonder request line: (919) 962-8989 if the future of radio is no longer in the stereo of our living rooms but on the World Wide Web. http://www.wxyc.org As always, new technology brings change that is both exciting [email protected] and scary. Local radio stations and the dedicated DJs and staffs who operate them are an integral part of vibrant local music communities, like the one we are lucky to have here in the Chapel Hill-Carrboro Staff NICOLE BOGAS area. With the proliferation of music services like XM satellite radio Editor-in-Chief and Live-365 Internet radio servers, it sometimes seems like the future EDITOR-IN-CHIEF: Nicole Bogas of local radio is doomed. -

The Dub June 2018

1 Spanners & Field Frequency Sound System, Reading Dub Club 12.5.18 2 Editorial Dub Front cover – Indigenous Resistance: Ethiopia Dub Journey II Dear Reader, Welcome to issue 25 for the month of Levi. This is our 3rd anniversary issue, Natty Mark founding the magazine in June 2016, launching it at the 1st Mikey Dread Festival near Witney (an event that is also 3 years old this year). This summer sees a major upsurge in events involving members of The Dub family – Natty HiFi, Jah Lambs & Lions, Makepeace Promotions, Zion Roots, Swindon Dub Club, Field Frequency Sound System, High Grade and more – hence the launch of the new Dub Diary Newsletter at sessions. The aim is to spread the word about forthcoming gigs and sessions across the region, pulling different promoters’ efforts together. Give thanks to the photographers who have allowed us to use their pictures of events this month. We welcome some new writers this month too – thanks you for stepping up Benjamin Ital and Eric Denham (whose West Indian Music Appreciation Society newsletter ran from 1966 to 1974 and then from 2014 onwards). Steve Mosco presents a major interview with U Brown from when they recorded an album together a few years ago. There is also an interview with Protoje, a conversation with Jah9 from April’s Reggae Innovations Conference, a feature on the Indigenous Resistance collective, and a feature on Augustus Pablo. Welcome to The Dub Editor – Dan-I [email protected] The Dub is available to download for free at reggaediscography.blogspot.co.uk and rastaites.com The Dub magazine is not funded and has no sponsors.