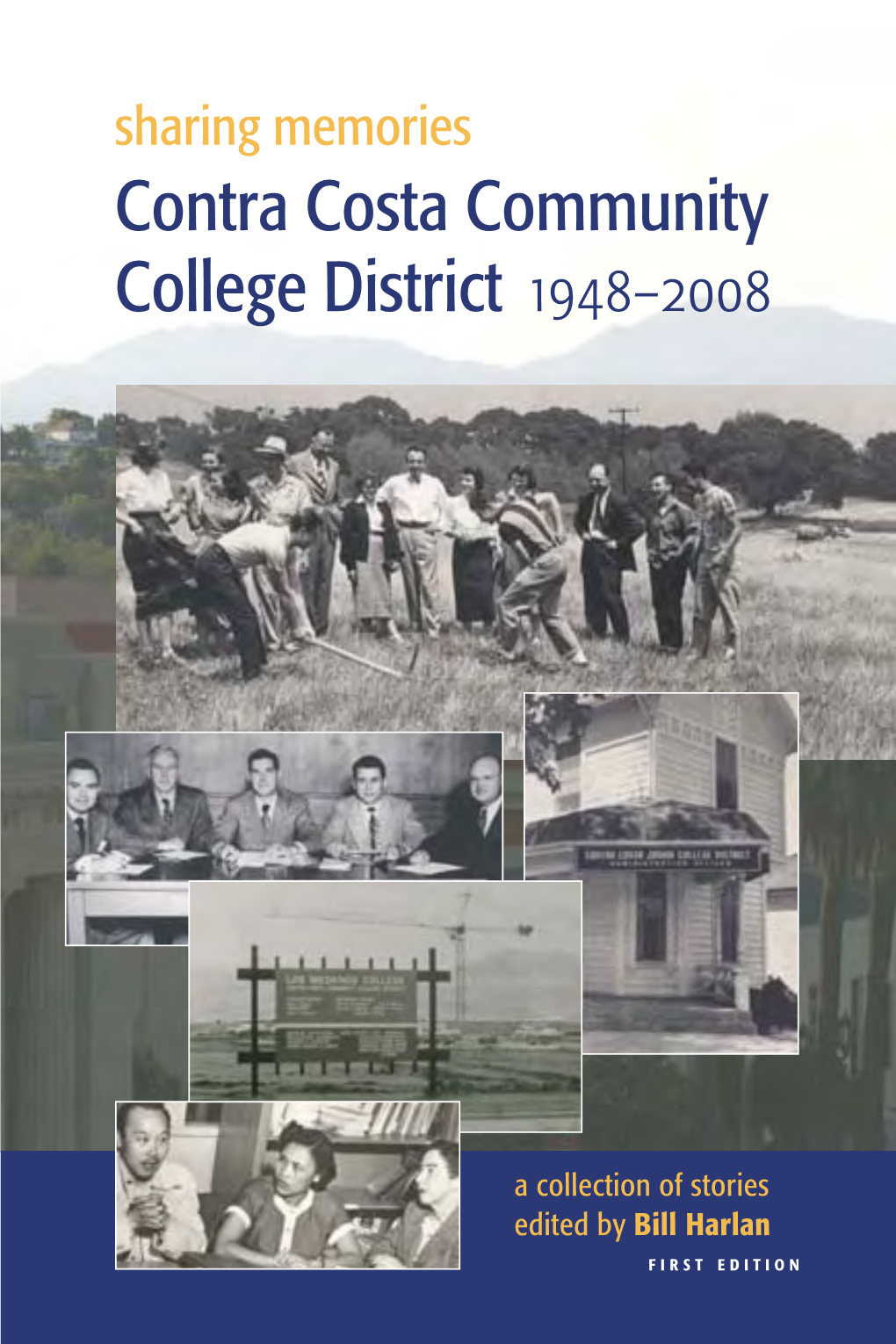

Sharing Memories Contra Costa Community College District 1948–2008

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vol 39 No 48 November 26

Notice of Forfeiture - Domestic Kansas Register 1 State of Kansas 2AMD, LLC, Leawood, KS 2H Properties, LLC, Winfield, KS Secretary of State 2jake’s Jaylin & Jojo, L.L.C., Kansas City, KS 2JCO, LLC, Wichita, KS Notice of Forfeiture 2JFK, LLC, Wichita, KS 2JK, LLC, Overland Park, KS In accordance with Kansas statutes, the following busi- 2M, LLC, Dodge City, KS ness entities organized under the laws of Kansas and the 2nd Chance Lawn and Landscape, LLC, Wichita, KS foreign business entities authorized to do business in 2nd to None, LLC, Wichita, KS 2nd 2 None, LLC, Wichita, KS Kansas were forfeited during the month of October 2020 2shutterbugs, LLC, Frontenac, KS for failure to timely file an annual report and pay the an- 2U Farms, L.L.C., Oberlin, KS nual report fee. 2u4less, LLC, Frontenac, KS Please Note: The following list represents business en- 20 Angel 15, LLC, Westmoreland, KS tities forfeited in October. Any business entity listed may 2000 S 10th St, LLC, Leawood, KS 2007 Golden Tigers, LLC, Wichita, KS have filed for reinstatement and be considered in good 21/127, L.C., Wichita, KS standing. To check the status of a business entity go to the 21st Street Metal Recycling, LLC, Wichita, KS Kansas Business Center’s Business Entity Search Station at 210 Lecato Ventures, LLC, Mullica Hill, NJ https://www.kansas.gov/bess/flow/main?execution=e2s4 2111 Property, L.L.C., Lawrence, KS 21650 S Main, LLC, Colorado Springs, CO (select Business Entity Database) or contact the Business 217 Media, LLC, Hays, KS Services Division at 785-296-4564. -

September 2004 Unification News

september 04 10/1/04 1:31 PM Page 1 UnificationUnification NewsNews $2 Volume 23, No. 9 T HE N EWSPAPER OF THE U NIFICATION C OMMUNITY September 2004 PEACE AMBASSADORS TO THE HOLY LAND by Rev. Michael Jenkins is a profound soul who is one of the he pilgrimage most prominent is a historic sheikhs (imams) in journey of the Great Britain. He heart. While shared with us that the violence if anger is not trans- ragesT on both sides formed it is trans- (Buses were bombed in ferred, if hate is not Beer Sheva last week and transformed it will major attacks are going be transferred, if on in the Gaza Strip), our violence is not Peace Ambassadors are transformed it will opening doors in each and be transferred. We every city they go to. From must set the con- Ramallah to Jerusalem dition to transform we go back and forth and the hearts of our the doors are opening. Jewish and Mus- Yesterday we went to Jeri- lims and Christian cho, where Joshua brothers and sis- brought the walls down ters as well as our- not with violence but with selves. the unity of God's people. We must go to a Then later in the day we new level of heart- went to the Wall that is -the revolution of being erected between heart in which we Palestine and Israel. We feel God's love and could feel the power of the heart to com- God that is working to fort God. remove the need for such Today, our Euro- walls. -

Selections from the Henry J. Kaiser Pictorial Collection

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf958012j8 Online items available Henry J. Kaiser Pictorial Collection, bulk 1930-1960 Selections (1983.017-.019, and 1983.027) described and processed for digitization by California Heritage Staff, 1996-1997. Descriptions of other series added in 2020 by Bancroft Library staff, from pre-existing contents lists. The Bancroft Library 1997 and 2021 The Bancroft Library University of California Berkeley, CA 94720-6000 [email protected] URL: http://www.lib.berkeley.edu/libraries/bancroft-library Henry J. Kaiser Pictorial BANC PIC 1983.001-.075 1 Collection, bulk 1930-1960 Contributing Institution: The Bancroft Library Title: Henry J. Kaiser pictorial collection Creator: Kaiser, Henry J., 1882- Creator: Henry J. Kaiser Company Creator: Kaiser Industries Corporation Creator: Kaiser Motors Corporation Creator: Kaiser Steel Corporation Creator: Kaiser Shipyards (Richmond, Calif.) Creator: Kaiser-Frazer Corp. Identifier/Call Number: BANC PIC 1983.001-.075 Physical Description: 200000 photographs (approximately 200,000 items (photographic prints, negatives, and albums), some design drawings and plans, and 909 digital objects) Date (bulk): bulk 1930-1976 Abstract: The Henry J. Kaiser Pictorial Collection contains an estimated 200,000 items, chiefly photographs, documenting the activities, projects, and products of the various companies that comprised Kaiser Industries, as well as photographs of Kaiser family members and associates. Subjects pictured include the Hoover, Parker, Bonneville, Grand Coulee, and Shasta Dams; the Kaiser shipyards in Richmond, California, including its products, workers and workers' housing conditions; Kaiser-Frazer automobiles, Kaiser Willys, Kaiser Steel, Kaiser Hospitals, and other Kaiser corporations in the San Francisco Bay Area and Hawaii, with some international content as well. -

Wxw Holds Keynote on Wxw NOW Streaming

wXw holds keynote on wXw NOW streaming service, announces details on Germany's first wrestling network wXw just announced the first in-depth details on our new "wXw NOW" streaming network, which will launch one month from now on 8/13 at www.wxwnow.de. It will not just be a collection of shows like a lot of companies offer for a monthly fee via Pivotshare but also offer original content and a lot of archived shows, some dating back as far as 2006. We will also have our uniquely designed interface/UI, while hosting and infrastructure will be managed by Vimeo, our long-time streaming partner, dating back to 2013. Wrestling journalist Markus Gronemann (DarkMat.eu, Wrestling Observer) considers this to be the biggest launch of an over-the-top pro wrestling channel by a single promotion since New Japan World. wXw Managing Director Christian Jakobi held a keynote presentation tonight at 8 pm CEST at the wXw Wrestling Academy training school, which was streamed live on Facebook (the video is available, albeit only in German, here) and talked about what future and past events and what kind of original content would be available. We had up to 750 viewers simultaneously on Facebook and also had some students and a trainer (Toby Blunt) in attendance to provide some crowd noise and cheering at key points during the announcement. Marquee Events are wXw's version of pay-per-view caliber shows, where feuds start and end and international talent often appears. There currently are 10 marquee events on the calendar, with some of them being multi-day shows: -

Background the Whirley Crane and Shipyard Number 3

Background The Whirley Crane and Shipyard Number 3 The “Whirley Crane,” so-called because its turret is capable of rotating 360 degrees, was built by Clyde Iron Works of Duluth, Minnesota in 1935. It was first used to build Grand Coulee Dam in Washington state, the second phase of which was done by a consortium of companies led by industrialist Henry J. Kaiser. In 1941, the crane was shipped by barge down the Columbia River and down the coast to Todd California Shipbuilding in Richmond, which later became Shipyard No 1 of Kaiser’s Richmond shipbuilding enterprise. In this location, it and dozens of others like it dominated the skyline of Richmond’s southern waterfront. Crane Facts: Weight: 229,000 pounds Boom length: 110 feet Diameter of turntable assembly: 28 feet Lifting capacity: 166,000 Original cost: $32,000 The use of Whirley Cranes was a major innovation in the mass production of ships. The cranes made it possible to turn huge ship structural pieces around and over during the pre-assembly process so that novice welders could complete relatively simple welding seams parallel to the ground. The cranes were also used in groups – as many as four cranes working together -- to move large pre-assembled parts of a ship into place in the basins so the ship could be fitted together, generally by welding. The result was a previously unimagined rate of production. A total of 747 ships were produced in the Kaiser shipyards in Richmond from 1942-1945. After the war, this crane was acquired by Parr-Richmond Terminal, which later became Levin-Richmond Terminal Corporation. -

ACCREDITING COMMISSION for COMMUNITY and JUNIOR COLLEGES Western Association of Schools and Colleges

ACCREDITING COMMISSION FOR COMMUNITY AND JUNIOR COLLEGES Western Association of Schools and Colleges COMMISSION ACTIONS ON INSTITUTIONS At its January 6-8, 2016 meeting, the Accrediting Commission for Community and Junior Colleges, Western Association of Schools and Colleges, took the following institutional actions on the accredited status of institutions: REAFFIRMED ACCREDITATION FOR 18 MONTHS ON THE BASIS OF A COMPREHENSIVE EVALUATION American River College Cosumnes River Folsom Lake College Sacramento City College Chabot College Las Positas College Citrus College Napa Valley College Santa Barbara City College Taft College ISSUED WARNING ON THE BASIS OF A COMPREHENSIVE EVALUATION Southwestern College REMOVED FROM WARNING ON THE BASIS OF A FOLLOW-UP REPORT WITH VISIT The Salvation Army College for Officer Training at Crestmont REMOVED SHOW CAUSE AND ISSUED WARNING ON THE BASIS OF A SHOW CAUSE REPORT WITH VISIT American Samoa Community College ELIGIBILITY DENIED California Preparatory College Accrediting Commission for Community and Junior Colleges January 2016 Commission Actions on Institutions THE COMMISSION REVIEWED THE FOLLOWING INSTITUTIONS AND CONTINUED THEIR ACCREDITED STATUS: MIDTERM REPORT Bakersfield College Cerro Coso Community College Porterville College College of the Sequoias Hawai’i Community College Honolulu Community College Kapi’olani Community College Kauai Community College Leeward Community College Windward Community College Woodland Community College Yuba College FOLLOW-UP REPORT Antelope Valley College De Anza College Foothill College Santa Ana College Windward Community College FOLLOW-UP REPORT WITH VISIT Contra Costa College Diablo Valley College Los Medanos College El Camino College Moreno Valley College Norco College Riverside City College Rio Hondo College . -

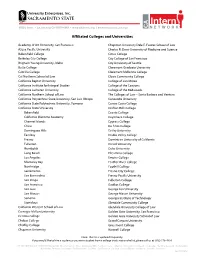

Affiliated Colleges and Universities

Affiliated Colleges and Universities Academy of Art University, San Francisco Chapman University Dale E. Fowler School of Law Azusa Pacific University Charles R. Drew University of Medicine and Science Bakersfield College Citrus College Berkeley City College City College of San Francisco Brigham Young University, Idaho City University of Seattle Butte College Claremont Graduate University Cabrillo College Claremont McKenna College Cal Northern School of Law Clovis Community College California Baptist University College of San Mateo California Institute for Integral Studies College of the Canyons California Lutheran University College of the Redwoods California Northern School of Law The Colleges of Law – Santa Barbara and Ventura California Polytechnic State University, San Luis Obispo Concordia University California State Polytechnic University, Pomona Contra Costa College California State University Crafton Hills College Bakersfield Cuesta College California Maritime Academy Cuyamaca College Channel Islands Cypress College Chico De Anza College Dominguez Hills DeVry University East Bay Diablo Valley College Fresno Dominican University of California Fullerton Drexel University Humboldt Duke University Long Beach El Camino College Los Angeles Empire College Monterey Bay Feather River College Northridge Foothill College Sacramento Fresno City College San Bernardino Fresno Pacific University San Diego Fullerton College San Francisco Gavilan College San Jose George Fox University San Marcos George Mason University Sonoma Georgia Institute of Technology Stanislaus Glendale Community College California Western School of Law Glendale University College of Law Carnegie Mellon University Golden Gate University, San Francisco Cerritos College Golden Gate University School of Law Chabot College Grand Canyon University Chaffey College Grossmont College Chapman University Hartnell College Note: This list is updated frequently. -

Annotated Bibliography for the Michigan Global/International Education Resource Center

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 395 835 SO 024 959 AUTHOR Barr, E. Gene TITLE Annotated Bibliography for the Michigan Global/International Education Resource Center. INSTITUTION International Inst. of Flint, MI. Michigan Global/International Education Resource Center. SPONS AGENCY Center for Global Partnership Foundation.; Japanese Society of Detroit Foundation, MI.; United States-Japan Foundation. PUB DATE Jun 94 NOTE 116p. AVAILABLE FROM International Institute of Flint, 515 Stevens, Flint, MI 48502. PUB TYPE Reference Materials Bibliographies (131) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC05 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Annotated Bibliographies; Area Studies; *Asian History; *Asian Studies; Cultural Background; Elementary Secondary Education; Foreign Countries; *Multicultural Education; *Non Western Civilization; Social Studies; World History IDENTIFIERS Japan; Michigan ABSTRACT This annotated bibliography on Japan serves as a useful compendium and guide to the holdings of the Michigan Global/International Education Resource Center, housed at the International Institute of Flint. The holdings will be disseminated throughout Michigan at workshops, seminars, and institutes. The bibliography includes background and instruction materials designed to foster multicultural, international, and global understandings in Michigan classrooms. The volume includes both print and non-print materials. Print materials include:(I) Background References--Books; (2) Background References--Newspapers, Journals, Maps, Brochures;(3) Exploratory Japanese-Language Instruction and Intensive Japanese Instruction Materials;(4) Curriculum Materials--Teacher and Student; and (5) Children's Literature and Literature Units. Eight appendices contains useful information for further research and reference use. (EH) ************ Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made * from the original document. * ************************************************A.***********,-- ,-A Ink a : a° A 9 EWE : was liTangiltall111 1191.1 tin CI) OiC) kr) C- U S DEPARTMENT Or- EDUCATION TO REPRODUCE AND Ed ,c5ton i t no. -

CSUSB Intellectual Life Fund Presentation: "The Alhambra and the Legacy of Al-Andalus"

California State University, San Bernardino CSUSB ScholarWorks CSUSB Video Recordings Arthur E. Nelson University Archives 6-10-2021 CSUSB Intellectual Life Fund Presentation: "The Alhambra and The Legacy of Al-Andalus" Inmaculada Correa Flores Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/csusb-video-recordings Recommended Citation Correa Flores, Inmaculada, "CSUSB Intellectual Life Fund Presentation: "The Alhambra and The Legacy of Al-Andalus"" (2021). CSUSB Video Recordings. 10. https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/csusb-video-recordings/10 This Video is brought to you for free and open access by the Arthur E. Nelson University Archives at CSUSB ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in CSUSB Video Recordings by an authorized administrator of CSUSB ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CSUSB Intellectual Life Fund Presentation "The Alhambra and The Legacy of Al-Andalus" by Inmaculada Correa Flores (June 10, 2021) START – 00:00:00 Jesus-David Jerez-Gomez: There's people joining now, so I think i'm going to start. Jesus-David Jerez-Gomez: Welcome to everyone who is here now, this is a wonderful day and location to learn about the legacy of Al-Andalus and the through sort of virtual tour of the Alhambra which you can see behind me, I wish I was there, but i'm going to be very soon, once we start. Jesus-David Jerez-Gomez: The presentation and first of all I would like to welcome everybody in in the name of various institutions and organizations mostly the World. Languages Department, they call the College of Arts and Letters. -

2019 Annual Report

ADDING DIMENSION Evangelical Community Hospital Annual Report 2019 TABLE OF CONTENTS 14 Board of Directors 16 02 Donor Report PRIME 48 06 Financial Report Geisinger Relationship 50 09 Community Benefit Report An Epic Conversion 12 Social Issues President’s Message Fiscal year 2019 was a period of extraordinary change at Evangelical Community Hospital. We signaled our strategic intent by announcing a stronger relationship with Geisinger. The unique agreement positions Evangelical to move forward as an independent community hospital while working more closely with Geisinger to make healthcare delivery in our region more efficient, cost- effective, and simply better for the patients we serve. The Hospital broke ground on our most ambitious construction project to date—a 112,000-square-foot expansion that, while not changing our bed complement, will significantly impact how care is delivered at Evangelical. Patients and families will be admitted to private rooms with their own bathrooms, and our caregivers will have the space and privacy they need to support the healing process. We started the move to a single, integrated electronic medical record. The transition will improve efficiency as providers and staff no longer must jump from one system to another in caring for patients. We shifted our strategic employee training to better address social issues impacting the community beyond our Hospital’s walls. We addressed suicide awareness, took a fresh, more personalized look at sexual harassment, moved to help alleviate the opioid addiction epidemic, and developed an award-winning human trafficking education model that is being replicated at other institutions in Pennsylvania. In short, we spent the fiscal year adding dimension—to our physical footprint, to our strategic direction, to our digital infrastructure, and to our community impact. -

FACULTY and ADMINISTRATORS Chapter Five Catalog 2020-2021

FACULTY AND ADMINISTRATORS chapter five catalog 2020-2021 Faculty and administrators 405 Index 411 404 FACULTY AND ADMINISTRATORS chapter five DIABLO VALLEY COLLEGE CATALOG 2020-2021 Faculty and administrators Faculty and administrators 405 FACULTY AND ADMINISTRATORS Abbott, Daniel Anisko, Melissa Barksdale, Jessica Index 411 faculty - architecture faculty - mathematics faculty - English B.A. - University of Oregon A.S. - San Joaquin Delta College B.A. - CSU Stanislaus B.S. - University of California, Davis M.A. - San Francisco State University Abedrabbo, Samar M.S. - University of California, Merced faculty - biology Beaulieu, Ellen A.A. - Irvine Valley Community College faculty - chemistry Antonakos, Cory B.S. - University of Georgia B.S. - University of California, Irvine faculty - chemistry P.h.D. - University of California, Santa B.S. - George Washington University Ph.D. - UC Berkeley Cruz M.S. - UC Berkeley Bennett, Troy faculty - art digital media Abele, Robert Aranda, Alberto B.F.A. - Plymouth State University faculty - counseling faculty - philosophy M.F.A. - Rochester Institute of Technology B.A. - University of Dayton certificate -CSU Los Angeles M.Div. - Mount St. Mary B.S., M.S. - CSU Los Angeles M.A. - Athenaeum of Ohio Bersamina, Leo Ph.D. - Marquette University faculty - art Arman, Beth A.A. - Cabrillo College senior dean - workforce development Agnost, Katy B.F.A. - San Francisco State University B.A. - University of Michigan, Ann Arbor M.F.A. - Yale University faculty – English M.A. - Harvard University, Kennedy B.A. - UC Davis School of Government M.A. - San Francisco State University Bessie, Adam faculty - English Akanyirige, Emmanuel Armendariz, Rosa B.A. - UC Davis faculty - mathematics dean - student engagement and equity M.A. -

Community Profile, November 2015

City of Alhambra General Plan Update Community Profile Prepared by: Rincon Consultants, Inc. 180 N. Ashwood Avenue Ventura, CA, 93003 November 2015 CONTENTS Contents ............................................................................................................................................... i Tables List .............................................................................................................................................. ii Figures List ............................................................................................................................................. iii Introduction ............................................................................................................................................ 1 Alhambra General Plan Update 2035 ................................................................................................. 1 Envision Alhambra 2035 ................................................................................................................. 1 The Region .......................................................................................................................................... 2 Purpose of this Report ........................................................................................................................ 5 Document Organization ................................................................................................................. 6 Community ............................................................................................................................................