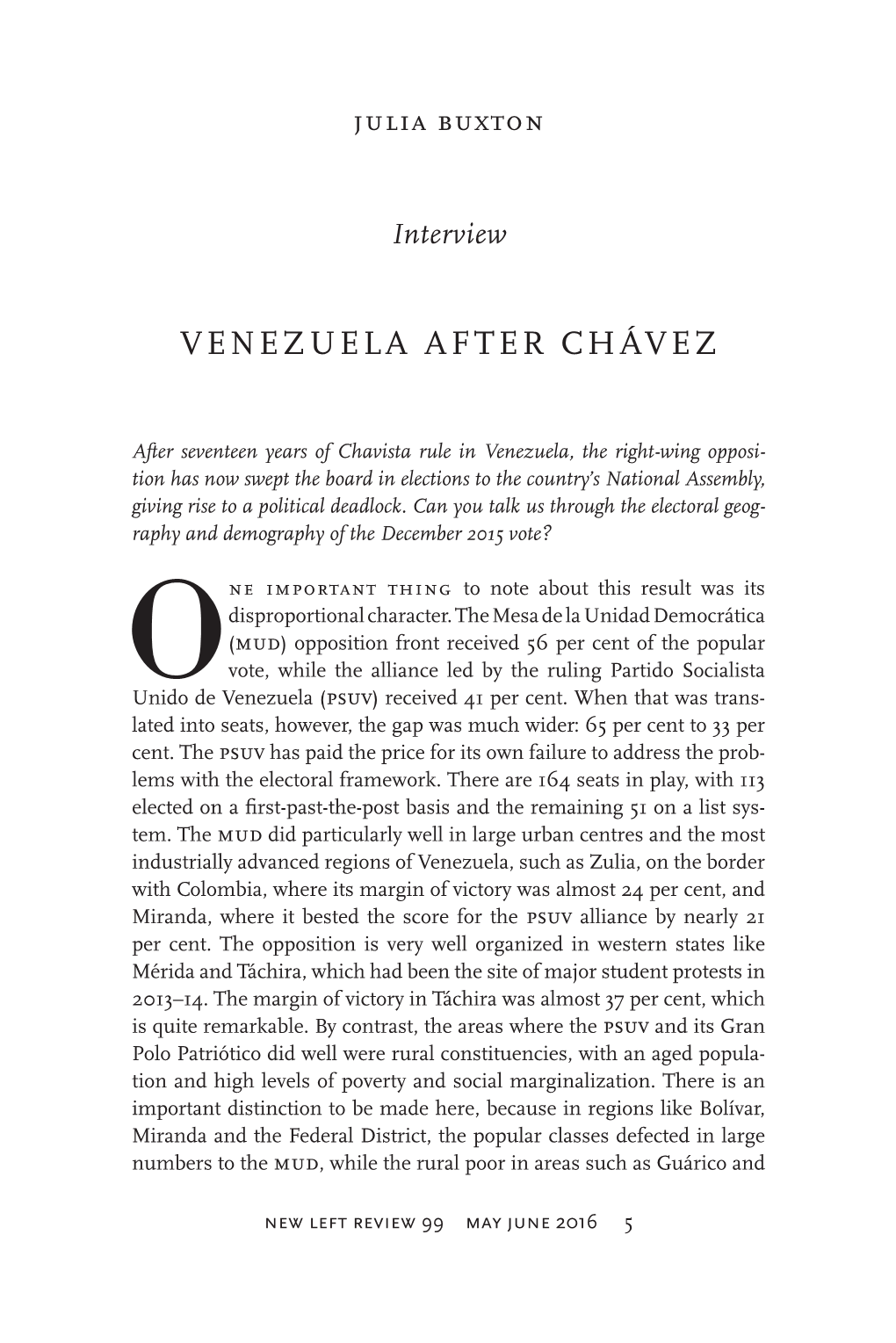

Venezuela After Chávez

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Department of the Interior

DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Road reconnaissance of anomalous radioactivity in the Early Proterozoic Roraima Group near Santa Elena de Uairen, Estado Bolivar, Venezuela by William E. Brooks1 and Fernando Nunez2 Open-File Report 91-632 1991 This report is preliminary and has not been reviewed for conformity with U.S. Geological Survey editorial standards or with the North American Stratigraphic Code. Denver, Colorado 2CVG-TECMIN Puerto Ordaz, Venezuela CONTENTS Page Introduction ........................................................ 1 Regional geology ..................................................... 1 Radioactivity in the Roraima Group ...................................... 2 Conclusions ......................................................... 2 References cited ..................................................... 3 FIGURES Figure 1. Venezuela location map showing sites discussed in text ............... 5 Figure 2. Sample locality map, Santa Elena de Uairen area ................... 6 TABLES Table 1. Scintillometer reading and sample description from localities with ~30 or more cps (counts per second) near Santa Elena de Uairen, Estado Bolivar, Venezuela ..................................... 8 Table 2. Analytical data for samples with ~30 or more cps (counts per second) near Santa Elena de Uairen, Estado Bolivar, Venezuela .............. 9 INTRODUCTION Radioactive anomalies are known in several regions of Venezuela and occurrences of uranium are known in clastic rocks of Jurassic age in western Venezuela; however, there are no uranium deposits in Venezuela (Rodriguez, 1986). The International Uranium Resources Evaluation Project (1980) considered the Early Proterozoic Roraima Group as a possible setting for Proterozoic unconformity and quartz-pebble conglomerate deposits. Apparent similarity of the geologic setting of the basal Roraima Group of southeastern Venezuela to unconformity U-Au deposits and quartz-pebble conglomerate Au-U deposits indicates that the Roraima Group may be an exploration target for uranium. -

Exploring Hugo Chávez's Use of Mimetisation to Build a Populist

Exploring Hugo Chávez’s use of mimetisation to build a populist hegemony in Venezuela Elena Block Rincones MSc, BA A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at The University of Queensland in 2013 School of Journalism and Communication Abstract “You too are Chávez”… (Hugo Chávez, 2012i) This thesis examines the political communication style developed by Hugo Chávez in his hegemonic construction of power and collective identity during the 14 years he governed Venezuela. This thesis is located in the field of political communication. A culturalist approach is used for the case, which prioritises issues of culture and power and acknowledges the role of human agency. Thus, it specifically focuses on the way the late President appears to have incrementally built an emotional, mimetic bond with his publics in a process that culminated in the mimetisation of the leader and his followers in a new collective, but top-down, identity called Chávez. This process expresses a hegemonic dynamic that involved the displacement of former dominant groups and rearrangement of power relations in Venezuela. The logic of mimetisation proposes an incremental logic of articulation whereby I tried to make sense of Chávez’s political communication style and success. It involves the study of the thread that joined together key elements in Chávez’s political communication style: hegemony and identity construction, political culture, populism, mediatisation, and communicational government. It is a style that appears to have exceeded classic populist forms of communication based on exerting an appeal to the people, towards more inclusive, participatory, symbolic-pragmatic forms of practising political communication that may have constituted the key to Chávez’s political success for 14 years. -

Electoral Observation in Venezuela 1998

Electoral Observations in the Americas Series, No. 19 Electoral Observation in Venezuela 1998 Secretary General César Gaviria Assistant Secretary General Christopher R. Thomas Executive Coordinator, Unit for the Promotion of Democracy Elizabeth M. Spehar Electoral Observation in Venezuela, 1998 / Unit for the Promotion of Democracy. p. : ill. ; cm. - (Electoral Observations in the Americas Series, no. 19) ISBN 0-8270-4122-5 1. Elections--Venezuela. 2. Election monitoring--Venezuela. I. Organization of American States. Unit for the Promotion of Democracy. II. Series JL3892 .O27 1999 (E) This publication is part of a series of UPD publications of the General Secretariat of the Organization of American States. The ideas, thoughts, and opinions expressed are not necessarily those of the OAS or its member states. The opinions expressed are the responsibility of the authors. OEA/Ser.D/XX SG/UPD/II.19 July 29, 1999 Original: Spanish Electoral Observation in Venezuela 1998 General Secretariat Organization of American States Washington, D.C. 20006 1999 This report was produced under the technical supervision of Edgardo C. Reis, Chief of the Mission, Special Advisor of the Unit for the Promotion of Democracy, and with the assistance of Steve Griner, Deputy Chief of the Mission and, Senior Specialist of the Unit for the Promotion of Democracy (UPD). Design and composition of this publication was done by the Information and Dialogue Section of the UPD, headed by Caroline Murfitt-Eller. Betty Robinson helped with the editorial review of this report and Dora Donayre and Esther Rodriguez with its production. Copyright Ó 1999 by OAS. All rights reserved. This publication may be reproduced provided credit is given to the source. -

Venezuela: Un Equilibrio Inestable

REVISTA DE CIENCIA POLÍTICA / VOLUMEN 39 / N° 2 / 2019 / 391-408 VENEZUELA: AN UNSTABLE EQUILIBRIUM Venezuela: un equilibrio inestable DIMITRIS PANTOULAS IESA Business School, Venezuela JENNIFER MCCOY Georgia State University, USA ABSTRACT Venezuela’s descent into the abyss deepened in 2018. Half of the country’s GDP has been lost in the last five years; poverty and income inequality have deepened, erasing the previous gains from the earlier years of the Bolivarian Revolution. Sig- nificant economic reforms failed to contain the hyperinflation, and emigration ac- celerated to reach three million people between 2014 and 2018, ten percent of the population. Politically, the government of Nicolás Maduro completed its authorita- rian turn following the failed Santo Domingo dialogue in February, and called for an early election in May 2018. Maduro’s victory amidst a partial opposition boycott and international condemnation set the stage for a major constitutional clash in January 2019, when the world was divided between acknowledging Maduro’s se- cond term or an opposition-declared interim president, Juan Guaido. Key words: Venezuela, Nicolás Maduro, economic crisis, hyperinflation, elections, electoral legitimacy, authoritarianism, polarization RESUMEN El descenso de Venezuela en el abismo se profundizó en 2018. La mitad del PIB se perdió en los últimos cinco años; la pobreza y la desigualdad de ingresos se profundizaron, anulando los avances de los primeros años de la Revolución Bolivariana. Las importantes reformas económicas no lograron contener la hiperinflación y la emigración se aceleró para llegar a tres millones de personas entre 2014 y 2018, el diez por ciento de la población. Políticamen- te, el gobierno de Nicolás Maduro completó su giro autoritario luego del fracasado proceso de diálogo de Santo Domingo en febrero, y Maduro pidió una elección adelantada en mayo de 2018. -

Analyzing Obstacles to Venezuela's Future

CSIS BRIEFS CSIS Analyzing Obstacles to Venezuela’s Future By Moises Rendon, Mark Schneider, & Jaime Vazquez NOVEMBER 2019 THE ISSUE Despite stiff sanctions, diplomatic isolation, and internal civil protests, Nicolas Maduro and his inner circle have resisted the pressures to negotiate an exit. Three internationally-sponsored dialogue processes and two efforts at mediated negotiations within the last five years have failed, with Maduro using the time to intensify his hold on power. Different factors are impeding a transition in Venezuela. This brief investigates challenges and opportunities to help support a transition toward democracy. It describes the possible role of a Track II diplomacy initiative to produce a feasible exit ramp for Maduro—essentially the achievement of significant progress outside of the formal negotiation process. The brief also discusses potential roles for chavistas in today’s struggle and for ‘day after’ challenges, the required elements for a transitional justice process, and the basic conditions necessary for holding free and fair elections to elect a new president. BACKGROUND undiminished support from Russia, China, and Cuba, have Amid numerous blackouts, fuel shortages impacting complicated efforts to achieve a political accord leading to a agriculture and food production, and inflation on pace democratic transition. to reach over 10 million percent by the end of 2019, Venezuela’s humanitarian, economic, and political crisis QUICK FACTS has forced more than 4 million citizens to flee their • According to the United Nations, Venezuela will homeland. That number could surge past 5 million by the have over 5.3 million refugees by the end of 2019. end of 2019. -

A Decade Under Chávez Political Intolerance and Lost Opportunities for Advancing Human Rights in Venezuela

A Decade Under Chávez Political Intolerance and Lost Opportunities for Advancing Human Rights in Venezuela Copyright © 2008 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 1-56432-371-4 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch 350 Fifth Avenue, 34th floor New York, NY 10118-3299 USA Tel: +1 212 290 4700, Fax: +1 212 736 1300 [email protected] Poststraße 4-5 10178 Berlin, Germany Tel: +49 30 2593 06-10, Fax: +49 30 2593 0629 [email protected] Avenue des Gaulois, 7 1040 Brussels, Belgium Tel: + 32 (2) 732 2009, Fax: + 32 (2) 732 0471 [email protected] 64-66 Rue de Lausanne 1202 Geneva, Switzerland Tel: +41 22 738 0481, Fax: +41 22 738 1791 [email protected] 2-12 Pentonville Road, 2nd Floor London N1 9HF, UK Tel: +44 20 7713 1995, Fax: +44 20 7713 1800 [email protected] 27 Rue de Lisbonne 75008 Paris, France Tel: +33 (1)43 59 55 35, Fax: +33 (1) 43 59 55 22 [email protected] 1630 Connecticut Avenue, N.W., Suite 500 Washington, DC 20009 USA Tel: +1 202 612 4321, Fax: +1 202 612 4333 [email protected] Web Site Address: http://www.hrw.org September 2008 1-56432-371-4 A Decade Under Chávez Political Intolerance and Lost Opportunities for Advancing Human Rights in Venezuela I. Executive Summary .................................................................................................... 1 Political Discrimination ............................................................................................2 The Courts ...............................................................................................................3 -

Convocatoria 2013 Argentina

CONVOCATORIA 2013 PROYECTOS PRESENTADOS ARGENTINA Coproducción PROYECTO EMPRESA 327 CUADERNOS Gema Juarez (Argentina-60%) Lupe Films (Chile-40%) AIRE LIBRE Rizoma S.R.L. (Argentina-80%) Salado Media S.R.L. (Uruguay-20%) BLANCA LUZ Habitación 1520 Prod./Fundación Octubre (Argentina-80%) U FILMS (Uruguay-20%) CAMINO A LA PAZ Cataratas de Si S.A. (Argentina-75%) Cinenomada SRL (Bolivia-25%) DAMIANA Océano Films (Argentina-66,93%) Mauricio Rial Banti (Paraguay-33,07%) EL (IM) POSIBLE OLVIDO Cepa audiovisual SRL (Argentina-80%) Cacerola Films (MéXico-20%) EL CIUDADANO ILUSTRE Tv Abierta S.A. (Argentina-80%) A Contracorriente Films SL (España-20%) EL MISTERIO DE LA FELICIDAD BD Cine SRL (Argentina-70%) Total Entertainment (Brasil-30%) EL PERRO MOLINA Cinebruto Producciones (Argentina-80%) Cronopio Film (Uruguay-20%) FOLKLORE ARGENTINO Barakacine SRL (Argentina-80%) Zebra Producciones (España-20%) LA LIEBRE CIEGA Aeroplano Cine S.A. (Argentina-70%) Muiraquitá Filmes e Prod. Artísticas (Brasil-30%) LA LUZ INCIDENTE Tarea Fina SRL/Aire cine SRL (Argentina-80%) Seacuático SRL (Uruguay-20%) MALVA Big Bang Cine SRL (Argentina-70%) ICAIC (Cuba-30%) MI AMIGA DEL PARQUE Campo Cine S.R.L. (Argentina-80%) Mutante Cine S.R.L. (Uruguay-20%) NECRONOMICON Ajimolido Films SRL (Argentina-80%) Panda Comunicaçao (Brasil-20%) PASAJE DE VIDA Malkina Producciones/Diego Corsini (Argentina 50%) Hazlotú Producciones (España- 50%) RELATOS SALVAJES Capital Intelectual S.A. (Argentina-70%) El deseo D.A.S.L.U. (España-30%) SHOWROOM Magoya Films (Argentina-70%) Ondina Filmes Produçoes Artísticas (Brasil-30%) TERRIBLE Orsay Troupe SRL (Argentina-78%) OC Producciones LLC (Costa Rica-22%) VALDENSES Duermevela S.R.L. -

Venezuela & Ecuador This Week

VENEZUELA & ECUADOR THIS WEEK Member FINRA/SIPC Monday, February 26, 2018 Maduro’s approval rises to two-year high President Maduro’s approval rating increased government. In fact, the drop has been most to 26.1% in the February Datanálisis survey, a 4.4 precipitous in the approval of the opposition coalition percentage point increase from the last reading in organization, the Democratic Unity Roundtable (MUD). November 2017 of 21.7%. This is the highest reading in The percentage of respondents that have a positive this series in nearly two years (it stood at 26.8% in view of the MUD has declined from by 28.0 ppt since March of 2016). Maduro’s approval rating has risen by October 2016, from 59.7% to 31.7%. In the meantime, 8.7 percentage points from its low in July of 2017. The support for the governing PSUV party actually rose by survey of 1,000 respondents was conducted through 5.5ppt from November and now stands at 26.2%. The direct interviews between February 01 and 14 of 2018 gap between the support of these two organizations, and has a margin of error of ±3.04%. also of 5.5 points, stands at its lowest level since October 2013. Maduro remains highly unpopular, and the survey indicates that a majority of Venezuelans do not want It is possible that the strengthening of Maduro’s him to remain in the presidency. But the survey also approval may be nothing more than the reflection that shows a sustained decline in the approval rating of all he has emerged stronger from last year’s political opposition leaders, with the result that Maduro’s conflicts. -

How Energy Reforms Can Transform Venezuela's

“Venezuela Energética poses a necessary and urgent debate. López and Baquero provoke a conversation that Venezuelans need to have now, because the country must take advantage of the last opportunities of prosperity that oil could provide in the coming years. – Moisés Naím ” VENEZUELA ENERGÉTICA: HOW ENERGY REFORMS CAN TRANSFORM VENEZUELA’S FUTURE based on the new book by Leopoldo López and Gustavo Baquero Venezuelans have an uneasy relationship with oil. It is our most abundant resource, and we have economically diverse, socially stable, and allows the largest reserves on the planet. Yet, the mis- citizens to take personal ownership of their future. management of oil has also fostered political corruption, generated unstable boom-bust eco- Energy reform can also be the pivot point for a nomic cycles, and created a rent-seeking mentality new economic and social contract between the that distorts the relationship between the people people of Venezuela and their government. The and the state. right reform plan will not only reverse our eco- nomic decline, it can help rebuild trust, spread We believe it’s time to reverse this paradigm. Oil can economic and social benefits, and create the be transformed into a blessing, not a curse – if it is foundation for broader development. It can be managed honestly, productively, and transparently. a source of unity, not division, among our people. And it can also restore confidence within the Any agenda to reverse Venezuela’s economic international community that Venezuela is once devastation must begin with the energy sector. again a trusted partner for investment. It can provide a powerful springboard to recovery – and also pave the way to a Venezuela that is “We need to turn oil into our servant, rather than our master. -

University Microfilms International 300 N

INFORMATION TO USERS This reproduction was made from a copy of a document sent to us for microfilming. While the most advanced technology has been used to photograph and reproduce this document, the quality of the reproduction is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help clarify markings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1.The sign or “target” for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is “Missing Page(s)”. If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting through an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure complete continuity. 2. When an image on the Film is obliterated with a round black mark, it is an indication of either blurred copy because of movement during exposure, duplicate copy, or copyrighted materials that should not have been filmed. For blurred pages, a good image of the page can be found in the adjacent frame. If copyrighted materials were deleted, a target note will appear listing the pages in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., is part of the material being photographed, a definite method of “sectioning” the material has been followed. It is customary to begin filming at the upper left hand comer of a large sheet and to continue from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. If necessary, sectioning is continued again—beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. -

Venezuela RISK & COMPLIANCE REPORT DATE: September 2017

Venezuela RISK & COMPLIANCE REPORT DATE: September 2017 KNOWYOURCOUNTRY.COM Executive Summary - Venezuela Sanctions: The US has imposed sanctions blocking property and suspending entry of certain persons contributing to the situation in Venezuela. FAFT list of AML No Deficient Countries US Dept of State Money Laundering assessment Higher Risk Areas: Not on EU White list equivalent jurisdictions Corruption Index (Transparency International & W.G.I.)) World Governance Indicators (Average Score) Failed States Index (Political Issues)(Average Score) International Narcotics Control Majors List - Cited Compliance with FATF 40 + 9 Recommendations Medium Risk Areas: Major Investment Areas: Agriculture - products: corn, sorghum, sugarcane, rice, bananas, vegetables, coffee; beef, pork, milk, eggs; fish Industries: petroleum, construction materials, food processing, textiles; iron ore mining, steel, aluminum; motor vehicle assembly, chemical products, paper products Exports - commodities: petroleum, bauxite and aluminum, minerals, chemicals, agricultural products, basic manufactures Exports - partners: US 39.1%, China 14.3%, India 12%, Netherlands Antilles 7.8%, Cuba 4.6% (2012) Imports - commodities: agricultural products, livestock, raw materials, machinery and equipment, transport equipment, construction materials, medical equipment, pharmaceuticals, chemicals, iron and steel products Imports - partners: US 31.7%, China 16.8%, Brazil 9.1%, Colombia 4.8% (2012) Investment Restrictions: The Venezuelan National Assembly passed legislation in 2010 designed to create a communal state and economy, privileging public-sector economic institutions and reducing the space for private-sector participation. Venezuela's legal framework for foreign investment requires equal treatment for both foreign and local companies, with the exception of a few sectors in which the state or Venezuelan nationals must be majority owners, including hydrocarbons and the media. -

ORIGIN and DEVELOPMENT of WHALEWATCHING in the STATE of ARAGUA, VENEZUELA: LAYING the GROUNDWORK for SUSTAINABILITY (Working Paper)

ORIGIN AND DEVELOPMENT OF WHALEWATCHING IN THE STATE OF ARAGUA, VENEZUELA: LAYING THE GROUNDWORK FOR SUSTAINABILITY (Working paper) Jaime Bolaños-Jiménez 1 Auristela Villarroel-Marin 1 , 2 E.C.M. Parsons 3 Naomi A. Rose 4 1 Sociedad Ecológica Venezolana Vida Marina (Sea Vida), A.P. 162, Cagua, Estado Aragua, Venezuela 2122. e-mail: [email protected] 2 Universidad Pedagógica Experimental Libertador (UPEL), Instituto Universitario Rafael Alberto Escobar Lara, Av. Las Delicias, Departamento de Biología, Maracay, Estado Aragua, Venezuela. 3 Department of Environmental Science & Policy, George Mason University, Fairfax, VA 22030, USA. e-mail: [email protected] 4 Humane Society International, 700 Professional Drive, Gaithersburg, MD 20879, USA. e-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT Whalewatching potential in Venezuelan waters is considered to be “moderate to considerable” by experts. Since 2001, the local non-governmental organization (NGO) Sociedad Ecológica Venezolana Vida Marina (Sea Vida) has been promoting responsible whalewatching in the “Municipio Ocumare de la Costa de Oro”, State of Aragua. Here, we review the origin and development of whalewatching in Ocumare de la Costa de Oro, as detailed below. 1) Scientific research. Research effort dates back to 1996-1998, when researchers of the Ministry of Environment evaluated the status of cetacean populations in this area. Since 2000-2001, research efforts have been accomplished by Sea Vida’s teams and independent researchers. Target species include Atlantic spotted (Stenella frontalis) and bottlenose (Tursiops truncatus) dolphins and Bryde’s whales (Balaenoptera edeni). The encounter rate with cetaceans is approximately 70%. 2) Regulatory framework. No specific regulations exist in Venezuela for whalewatching. Currently, a proposal presented by Sea Vida for the enactment of regulations at the national level is being reviewed by the MINAMB.