Texas Curriculum Units* * Download Other Enduring Community Units (Accessed September 3, 2009)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cassociation^ of Southern Women for the "Prevention of Cynching ******

cAssociation^ of Southern Women for the "Prevention of Cynching JESSIE DANIEL AMES, EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR MRS. ATTWOOD MARTIN MRS. W. A. NEWELL CHAIRMAN 703 STANDARD BUILDING SECRETARY-TREASURER Louisville, Ky. Greensboro, n. c. EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE cAtlanta, Qa MRS. J. R. CAIN, COLUMBIA, S. C. MRS. GEORGE DAVIS, ORANGEBURG, S. C. MRS. M. E. TILLY, ATLANTA, GA. MRS. W. A. TURNER, ATLANTA, GA. MRS. E. MARVIN UNDERWOOD, ATLANTA, GA. January 7, 1932 Composite Picture of Lynching and Lynchers "Vuithout exception, every lynching is an exhibition of cowardice and cruelty. 11 Atlanta Constitution, January 16, 1931. "The falsity of the lynchers' pretense that he is the guardian of chastity." Macon News, November 14, 1930. "The lyncher is in very truth the most vicious debaucher of spirit ual values." Birmingham Age Herald, November 14, 1930. "Certainly th: atrocious barbarities of the mob do not enhance the security of women." Charleston, S. C. Evening lost. "Hunt down a member of a lynching mob and he will usually be found hiding behind a woman's skirt." Christian Century, January 8, 1931. ****** In the year 1930, Texas and Georgia, were black spots on the map. This year, 1931, those two states cleaned up and came thro with "no lynchings." But honors arc even. Two states, Louisiana and Tennessee, with "no lynchings" in 1930, add one each in 1931. Florida and Mississippi were the only two states having lynchings in both years. Five of the eight in the South were in these two States alone. Jessie Daniel limes Executive Director Association of Southern Women for the Prevention of Lynching CENTRAL COUNCIL Representatives at Large Mrs. -

BIGGERS, JOHN THOMAS, 1924-2001. John Biggers Papers, 1950-2001

BIGGERS, JOHN THOMAS, 1924-2001. John Biggers papers, 1950-2001 Emory University Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library Atlanta, GA 30322 404-727-6887 [email protected] Collection Stored Off-Site All or portions of this collection are housed off-site. Materials can still be requested but researchers should expect a delay of up to two business days for retrieval. Descriptive Summary Creator: Biggers, John Thomas, 1924-2001. Title: John Biggers papers, 1950-2001 Call Number: Manuscript Collection No. 1179 Extent: 31 linear feet (62 boxes), 6 oversized papers boxes and 2 oversized papers folders (OP), 2 oversized bound volumes (OBV), 1 extra-oversized paper (XOP), and AV Masters: .25 linear feet (1 box) Abstract: Papers of African American mural artist and professor John Biggers including correspondence, photographs, printed materials, professional materials, subject files, writings, and audiovisual materials documenting his work as an artist and educator. Language: Materials entirely in English. Administrative Information Restrictions on Access Special restrictions apply: Use copies have not been made for audiovisual material in this collection. Researchers must contact the Rose Library at least two weeks in advance for access to these items. Collection restrictions, copyright limitations, or technical complications may hinder the Rose Library's ability to provide access to audiovisual material. Collection stored off-site. Researchers must contact the Rose Library in advance to access this collection. Terms Governing Use and Reproduction All requests subject to limitations noted in departmental policies on reproduction. Emory Libraries provides copies of its finding aids for use only in research and private study. -

ABSTRACT “The Good Angel of Practical Fraternity:” the Ku Klux Klan in Mclennan County, 1915-1924. Richard H. Fair, M.A. Me

ABSTRACT “The Good Angel of Practical Fraternity:” The Ku Klux Klan in McLennan County, 1915-1924. Richard H. Fair, M.A. Mentor: T. Michael Parrish, Ph.D. This thesis examines the culture of McLennan County surrounding the rise of the Ku Klux Klan in the 1920s and its influence in central Texas. The pervasive violent nature of the area, specifically cases of lynching, allowed the Klan to return. Championing the ideals of the Reconstruction era Klan and the “Lost Cause” mentality of the Confederacy, the 1920s Klan incorporated a Protestant religious fundamentalism into their principles, along with nationalism and white supremacy. After gaining influence in McLennan County, Klansmen began participating in politics to further advance their interests. The disastrous 1922 Waco Agreement, concerning the election of a Texas Senator, and Felix D. Robertson’s gubernatorial campaign in 1924 represent the Klan’s first and last attempts to manipulate politics. These failed endeavors marked the Klan’s decline in McLennan County and Texas at large. “The Good Angel of Practical Fraternity:” The Ku Klux Klan in McLennan County, 1915-1924 by Richard H. Fair, B.A. A Thesis Approved by the Department of History ___________________________________ Jeffrey S. Hamilton, Ph.D., Chairperson Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Baylor University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Approved by the Thesis Committee ___________________________________ T. Michael Parrish, Ph.D., Chairperson ___________________________________ Thomas L. Charlton, Ph.D. ___________________________________ Stephen M. Sloan, Ph.D. ___________________________________ Jerold L. Waltman, Ph.D. Accepted by the Graduate School August 2009 ___________________________________ J. -

Exhibiting Racism: the Cultural Politics of Lynching Photography Re-Presentations

EXHIBITING RACISM: THE CULTURAL POLITICS OF LYNCHING PHOTOGRAPHY RE-PRESENTATIONS by Erika Damita’jo Molloseau Bachelor of Arts, Western Michigan University, 2001 Master of Arts, University of Pittsburgh, 2003 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2008 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented August 8, 2008 by Erika Damita’jo Molloseau It was defended on September 1, 2007 and approved by Cecil Blake, PhD, Department Chair and Associate Professor, Department of Africana Studies Scott Kiesling, PhD, Department Chair and Associate Professor, Department of Linguistics Lester Olson, PhD, Professor, Department of Communication Dissertation Advisor, Ronald Zboray, PhD, Professor and Director of Graduate Study, Department of Communication ii Copyright © by Erika Damita’jo Molloseau 2008 iii EXHIBITING RACISM: THE CULTURAL POLITICS OF LYNCHING PHOTOGRAPHY RE-PRESENTATIONS Erika Damita’jo Molloseau, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2008 Using an interdisciplinary approach and the guiding principles of new historicism, this study explores the discursive and visual representational history of lynching to understand how the practice has persisted as part of the fabric of American culture. Focusing on the “Without Sanctuary: Lynching Photography in America” exhibition at three United States cultural venues I argue that audiences employ discernible meaning making strategies to interpret these lynching photographs and postcards. This examination also features analysis of distinct institutional characteristics of the Andy Warhol Museum, Martin Luther King Jr. National Historic Site, and the Charles H. Wright Museum of African American History, alongside visual rhetorical analysis of each site’s exhibition contents. -

Congressional Record United States Th of America PROCEEDINGS and DEBATES of the 112 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 112 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION Vol. 157 WASHINGTON, MONDAY, MARCH 14, 2011 No. 38 House of Representatives The House met at noon and was I have visited Japan twice, once back rifice our values and our future all in called to order by the Speaker pro tem- in 2007 and again in 2009 when I took the name of deficit reduction. pore (Mr. CAMPBELL). my oldest son. It’s a beautiful country; Where Americans value health pro- f and I know the people of Japan to be a tections, the Republican CR slashes resilient, generous, and hardworking funding for food safety inspection, DESIGNATION OF SPEAKER PRO people. In this time of inexpressible community health centers, women’s TEMPORE suffering and need, please know that health programs, and the National In- The SPEAKER pro tempore laid be- the people of South Carolina and the stitutes of Health. fore the House the following commu- people of America stand with the citi- Where Americans value national se- nication from the Speaker: zens of Japan. curity, the Republican plan eliminates WASHINGTON, DC, May God bless them, and may God funding for local police officers and March 14, 2011. continue to bless America. firefighters protecting our commu- I hereby appoint the Honorable JOHN f nities and slashes funding for nuclear CAMPBELL to act as Speaker pro tempore on nonproliferation, air marshals, and this day. FUNDING THE FEDERAL Customs and Border Protection. Where JOHN A. BOEHNER, GOVERNMENT Americans value the sacrifice our men Speaker of the House of Representatives. -

The Quad (The 2017 Alumni Magazine)

THE QUAD | ALUMNI MAGAZINE | FALL 2017 Dedman CELEBRATING ALUMNI 30 Years of the Distinguished Alumni Awards YEARS OF DISTINGUISHED ALUMNI AWARD30 WINNERS THE QUAD | VOL 48 Dean Director of Alumni Relations Photographers SMU Dedman School of Law Jennifer M. Collins Abby N. Ruth ’06 Thomas Garza, Hillsman Office of Alumni Relations Jackson, Bret Redman P.O. Box 750116 Dallas, TX 75275-0116 Director of External Relations Managing Editor 214-768-4LAW(4529) Lynn M. Dempsey Patricia S. Heard Printer ColorDynamics Email: [email protected] Director of Writers & Contributors www.law.smu.edu Communications & Marketing Mark Curriden, Kristy A. Offenburger Patricia S. Heard, Brooks Igo The Quad is published for graduates and friends of the law school. Reproduction in whole or in part of this magazine without permission is prohibited. SMU will not discriminate in any program or activity on the basis of race, color, religion, national origin, sex, age, disability, genetic information, veteran status, sexual orientation, or gender identity and expression. The Executive Director for Access and Equity/Title IX Coordinator is designated to handle inquiries regarding nondiscrimination policies and may be reached at the Perkins Administration Building, Room 204, 6425 Boaz Lane, Dallas, TX 75205, 214-768-3601, [email protected]. Dedman SCHOOL OF LAW IN THIS ISSUE FALL 2017 Features 4 | 30th Annual Distinguished Alumni Awards A special evening honors six new award recipients and commemorates 30 years of winners and their enormous contributions to the law school, the profession and the community. 12 | Spring Break 2017: DISTINGUISHED ALUMNI Crayons as Contraband 4 Professor Natalie Nanasi and eight Dedman Law students volunteer at AWARD WINNERS Karnes County Residential Center to help immigrant mothers and children fleeing violence. -

Anniversary Meetings H S S Chicago 1924 December 27-28-29-30 1984

AHA Anniversary Meetings H S S 1884 Chicago 1924 1984 December 27-28-29-30 1984 r. I J -- The United Statei Hotel, Saratop Spring. Founding ike of the American Histoncal Anociation AMERICA JjSTORY AND LIFE HjcItl An invaluable resource for I1.RJC 11’, Sfl ‘. “J ) U the professional 1< lUCEBt5,y and I for the I student • It helps /thej beginning researcher.., by puttmq basic information at his or her fingertips, and it helps the mature scholar to he sttre he or she hasn ‘t missed anything.” Wilbur R. Jacobs Department of History University of California, Santa Barbara students tote /itj The indexing is so thorough they can tell what an article is about before they even took up the abstract Kristi Greenfield ReferencelHistory Librarian University of Washington, Seattle an incomparable way of viewing the results of publication by the experts.” Aubrey C. Land Department of History University of Georgia, Athens AMERICA: HISTORY AND LIFE is a basic resource that belongs on your library shelves. Write for a complimentary sample copy and price quotation. ‘ ABC-Clio Information Services ABC Riviera Park, Box 4397 /,\ Santa Barbara, CA 93103 CLIO SAN:301-5467 AMERICAN HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION Ninety-Ninth Annual Meeting A I { A HISTORY OF SCIENCE SOCIETY Sixtieth Annual Meeting December 27—30, 1984 CHICAGO Pho1tg aph qf t/u’ Umted States Hotel are can the caller turn of (a urge S. B airier, phato a1bher Saratoga Sprzng, V) 1 ARTHUR S. LINK GEORGE H. DAVIS PROFESSOR Of AMERICAN HISTORY PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESIDENT OF THE AMERICAN HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION AMERICAN HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION 4t)f) A Street SE, Washington, DC 20003 1984 OFfICERS President: ARTHUR S. -

INFORMATION to USERS This Manuscript Has Been Reproduced

INFO RM A TIO N TO U SER S This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI film s the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be fromany type of con^uter printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependentquality upon o fthe the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and inqjroper alignment can adverse^ afreet reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note wiD indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one e3q)osure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photogr^hs included inoriginal the manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for aiy photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI direct^ to order. UMJ A Bell & Howell Information Company 300 North Zeeb Road. Ann Arbor. Ml 48106-1346 USA 313.'761-4700 800/521-0600 LAWLESSNESS AND THE NEW DEAL; CONGRESS AND ANTILYNCHING LEGISLATION, 1934-1938 DISSERTATION presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of the Ohio State University By Robin Bernice Balthrope, A.B., J.D., M.A. -

Texas Civil Rights Trailblazers

Texas Civil Rights Trailblazers 9 Time • Handout 1-1: Complete List of Trailblazers (for teacher use) 3 short sessions (10 minutes per session) and 5 full • Handout 2-1: Sentence Strips, copied, cut, and pasted class periods (50 minutes per period) onto construction paper • Handout 2-2: Categories (for teacher use) Overview • Handout 2-3: Word Triads Discussion Guide (optional), one copy per student This unit is initially phased in with several days of • Handout 3-1: Looping Question Cue Sheet (for teacher use) short interactive activities during a regular unit on • Handout 3-2: Texas Civil Rights Trailblazer Word Search twentieth-Century Texas History. The object of the (optional), one copy per student phasing activities is to give students multiple oppor- • Handout 4-1: Rubric for Research Question, one copy per tunities to hear the names of the Trailblazers and student to begin to become familiar with them and their • Handout 4-2: Think Sheet, one copy per student contributions: when the main activity is undertaken, • Handout 4-3: Trailblazer Keywords (optional), one copy students will have a better perspective on his/her per student Trailblazer within the general setting of Texas in the • Paint masking tape, six markers, and 18 sheets of twentieth century. scrap paper per class • Handout 7-1: Our Texas Civil Rights Trailblazers, one Essential Question copy per every five students • How have courageous Texans extended democracy? • Handout 8-1: Exam on Texas Civil Rights Trailblazers, one copy per student Objectives Activities • Students will become familiar with 32 Texans who advanced civil rights and civil liberties in Texas by Day 1: Mum Human Timeline (10 minutes) examining photographs and brief biographical infor- • Introduce this unit to the students: mation. -

The Story of Alma Bridwell White

HISTORICAL ESSAY: IN THE NAME OF GOD; AN AMERICAN STORY OF FEMINISM, RACISM, AND RELIGIOUS INTOLERANCE: THE STORY OF ALMA BRIDWELL WHITE. BY KRISTIN E. KANDT* FO REW O RD ............................................................................................ 753 I. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................... 754 II. THE STORY OF ALMA BRIDWELL WHITE'S EARLY LIFE, BREAKING OUT OF HER "PRISON WALLS.". .................... 758 A. From "Prison"to a Desire to Preach........................................................... 758 B. Alma's Marriageand her Return to "Prison"............................................ 761 III. FROM PREACHING TO THE "PILLAR OF FIRE," RELIGION LIBERATES ALMA WHITE FROM HER "PRISON" ....................765 IV. BALANCING PoLrCAL, SOCIAL, AND RELIGIOUS VIEWPOINTS ................. 776 A. ReligiousEquality, Suffrage, the ERA, and Legal Equality - Concepts M andated by the Bible ............................................................................. 776 B. Segregation, Racism, Feminism and the Ku Klux Klan: A Combination Divinely Ordainedby God ....................................................................... 783 C. Religious Intolerance- An Outgrowth of Feminism, Prohibition,and First Amendment Concerns.............................................................................. 790 V. CON CLU SIO N ........................................................................................ 794 FOREWORD I first conceived of this article while taking -

1St Independent Mixed Brigade (Imperial Japanese Army)

1st Independent Mixed Brigade (Imperial Japanese Army) WikiProject Japan. (Rated Stub-class, Low-importance). JapanWikipedia:WikiProject JapanTemplate:WikiProject JapanJapan-related articles. Japan portal. v. Stub-Class Japan-related articles. Low-importance Japan-related articles. WikiProject Japan articles. Stub-Class Asian military history articles. Asian military history task force articles. The 1st Independent Mixed Brigade, led by Major General Tachibana, the northern-most cluster or Groom Islands included, Yome-jima, Muko-jima, and NakÅdo-jima or Nakadachi-jima. The southern-most cluster known as the Mother Island of Haha-jima, Ane-jima, ImÅto-jima, Mei-jima and these groups of islands were by-passed when Iwo-jima was chosen to attack but were subjected to bombing and naval shelling by the U. S. military. The Japanese Imperial Army had Independent Mixed Brigades that were composed of various units detached from other ⦠Image: War flag of the Imperial Japanese Army. Image: Flag of Japan (1870 1999). Between 1937 and 1945 the Japanese Imperial Army stood up 136 Independent Mixed Brigades, typically composed of various units detached from other formations. Some were composed of separate, unaffiliated assets. These brigades were task organized under unified command and were normally used in support roles, as security, force protection, POW and internment camp guards and labor in occupied territories. An Independent Mixed Brigade had between 5,000 and 11,000 troops.[1]. Independent Mixed Brigades 独立混æˆæ—…団. Active. 1937-1945. All information for Mixed Brigades (Imperial Japanese Army)'s wiki comes from the below links. Any source is valid, including Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, and LinkedIn. -

Texas Curriculum Units* * Download Other Enduring Community Units (Accessed September 3, 2009)

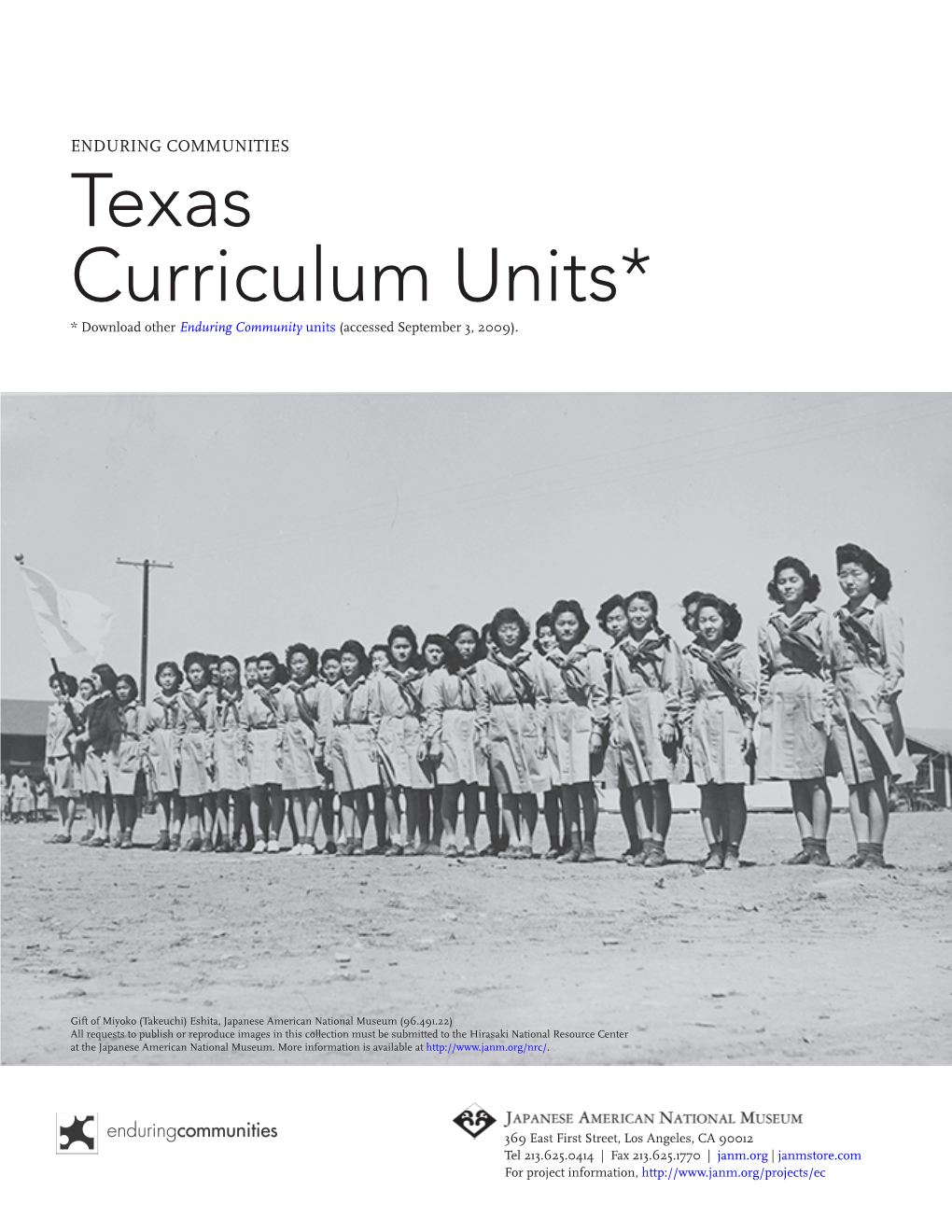

ENDURING COMMUNITIES Texas Curriculum Units* * Download other Enduring Community units (accessed September 3, 2009). Gift of Miyoko (Takeuchi) Eshita, Japanese American National Museum (96.491.22) All requests to publish or reproduce images in this collection must be submitted to the Hirasaki National Resource Center at the Japanese American National Museum. More information is available at http://www.janm.org/nrc/. 369 East First Street, Los Angeles, CA 90012 Tel 213.625.0414 | Fax 213.625.1770 | janm.org | janmstore.com For project information, http://www.janm.org/projects/ec Enduring Communities Texas Curriculum Writing Team G. Salvador Gutierrez Mark Hansen Jessica Jolliffe Mary Grace Ketner David Monteith, Jr. Linda O’Dell Lynne Smogur Photo by Richard M. Murakami Project Managers Allyson Nakamoto Jane Nakasako Cheryl Toyama Enduring Communities is a partnership between the Japanese American National Museum, educators, community members, and five anchor institutions: Arizona State University’s Asian Pacific American Studies Program University of Colorado, Boulder University of New Mexico UTSA’s Institute of Texan Cultures Davis School District, Utah 369 East First Street Los Angeles, CA 90012 Tel 213.625.0414 Fax 213.625.1770 janm.org | janmstore.com Copyright © 2009 Japanese American National Museum TEXAS Table of Contents 4 Project Overview of Enduring Communities: The Japanese American Experience in Arizona, Colorado, New Mexico, Texas, and Utah Curricular Units* 5 Introduction to the Curricular Units 6 Dialogue, Denial, Decision: