90 PP-AA Z-2T1?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Project – Additional Financing – Faridpur Water Supply Subproject

Initial Environmental Examination April 2017 BAN: Third Urban Governance and Infrastructure Improvement (Sector) Project – Additional Financing – Faridpur Water Supply Subproject Prepared by Local Government Engineering Department – Government of Bangladesh for the Asian Development Bank. This is an initial draft available on http://www.adb.org/projects/39295- 038/documents. CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (as of 3 March 2017) Currency Unit = BDT BDT1.00 = $0.01260 $1.00 = BDT79.36 ABBREVIATIONS ADB – Asian Development Bank AM – Accountability Mechanism AP – Affected Person BBS – Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics BSCIC – Bangladesh Small and Cottage Industries Corporation BDT – Bangladesh Taka BIWTA – Bangladesh Inland Water Transport Agency BMD – Bangladesh Meteorological Department BNBC – Bangladesh National Building Code BOD – Biochemical Oxygen Demand BOD5 – 5-day Biochemical Oxygen Demand BWDB – Bangladesh Water Development Board CC – cement concrete CCA – climate change adaptation COD – Chemical Oxygen Demand CRO – Complaint Receiving Officer CRIUP – Climate Resilient Integrated Urban Plan Reports dB – Decibel DFR – Draft Final Report DO – Dissolved Oxygen DoE – Department of Environment DPHE – Department of Public Heath Engineering EA – Environmental Assessment EARF – Environmental Assessment and Review Framework ECA – Environmental Conservation Act ECC – Environmental Clearance Certificate ECR – Environment Conservation Rules EIA – Environmental Impact Assessment EM&MP – Environmental Management & Monitoring Plan EMP – Environmental Management -

34418-023: Southwest Area Integrated Water Resources

Semiannual Environmental Monitoring Report Project No. 34418-023 December 2018 Southwest Area Integrated Water Resources Planning and Management Project - Additional Financing Prepared by Bangladesh Water Development Board for the People’s Republic of Bangladesh and the Asian Development Bank. This Semiannual Environmental Monitoring Report is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. Semi-Annual Environmental Monitoring Report, SAIWRPMP-AF, July-December 2018 Bangladesh Water Development Board SEMI-ANNUAL ENVIRONMENTAL MONITORING REPORT [Period July – December 2018] FOR Southwest Area Integrated Water Resources Planning and Management Project- Additional Financing Project Number: GoB Project No. 5151 Full Country Name: Bangladesh Financed by: ADB and Government of Bangladesh Prepared by: Bangladesh Water Development Board, Under Ministry of Water Resources, Govt. of Bangladesh. For: Asian Development Bank December 2018 Page | i Table of Contents Table of Contents .......................................................................................................................................... ii Executive -

Progress Report

Government of the People's Republic of Bangladesh Ministry of Local Government (Local Govt. Division) PROGRESS REPORT ZILLA ROAD MAINTENANCE AND IMPROVEMENT PRO (USAID PROJECT .388-0056) FOR THE MONTH OF MARCH '1985. BY Wilbur Smith and Associates In association with Bangladesh Consultants Ltd. and Public Administration Service ZILA ROADS MAINTENANCE AND IMPROVUIENT PROJECT USAIL) PROJLCT No. 388-0056 PROGRESS REX2 CRT March 1985 TAuLE OF CONTLNTS S u b j e c t. Page no. List of Exhibits ........................................ I...................... iv List of Appendices ............................................................ iv List Of Abbreviations ........................................................... v 1.0 GENRAL ............... .................................................1 2.0 ORGANIZATION AND MANAGEMENT ........................................... 1 3.0 HAINTENANCE SYSTEM AND SUP~iVISION .................................... 2 3.1 General ......................................................... 2 3.2 Sylhet District ................................................. 2 3.2.1 General ... .............................................. 2 3.2.2 Sylhet Maintenance Projects ............................. 3 3.3 Ranpui: Diqtrict ................................................ 5 3.3.1 General ................................................ 5 3.3.2 Rangpur Maintenance Projects ............................. 5 3.4 Faridpur District ............................................... 6 3.5 Maintenance Management ...................................... -

Diversity of Cropping Patterns and Land Use Practices in Faridpur Region

Bangladesh Rice J. 21 (2) : 157-172, 2017 Diversity of Cropping Patterns and Land Use Practices in Faridpur Region A B M Mostafizur1*, M A U Zaman1, S M Shahidullah1 and M Nasim1 ABSTRACT The development of agriculture sector largely depends on the reliable and comprehensive statistics of the existing cropping patterns, cropping intensity and crop diversity of a particular area, which will provide guideline to policy makers, researchers, extensionists and development workers. The study was conducted over all 29 upazilas of Faridpur region during 2015-16 using pre-tested semi-structured questionnaire with a view to document the existing cropping patterns, cropping intensity and crop diversity of this area. From the present study it was observed that about 43.23% net cropped area (NCA) was covered by only jute based cropping patterns on the other hand deep water ecosystem occupied about 36.72% of the regional NCA. The most dominant cropping pattern Boro−Fallow− Fallow occupied about 24.40% of NCA with its distribution over 28 out of 29. The second largest area, 6.94% of NCA, was covered by Boro-B. Aman cropping pattern, which was spread out over 23 upazilas. In total 141 cropping patterns were identified under this investigation. The highest number of cropping patterns was identified 44 in Faridpur sadar and the lowest was 12 in Kashiani of Gopalganj and Pangsa of Rajbari. The lowest crop diversity index (CDI) was reported 0.448 in Kotalipara followed by 0.606 in Tungipara of Gopalganj. The highest value of CDI was observed 0.981 in Faridpur sadar followed by 0.977 in Madhukhali of Faridpur. -

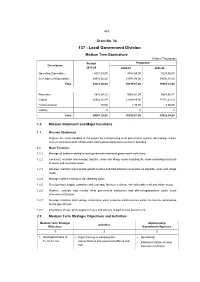

137 - Local Government Division

453 Grant No. 34 137 - Local Government Division Medium Term Expenditure (Taka in Thousands) Budget Projection Description 2019-20 2020-21 2021-22 Operating Expenditure 4321,54,00 4753,69,00 5229,06,00 Development Expenditure 29919,66,00 31541,98,00 34696,18,00 Total 34241,20,00 36295,67,00 39925,24,00 Recurrent 7815,04,16 9003,87,04 8807,80,41 Capital 26425,35,84 27289,84,96 31115,37,59 Financial Asset 80,00 1,95,00 2,06,00 Liability 0 0 0 Total 34241,20,00 36295,67,00 39925,24,00 1.0 Mission Statement and Major Functions 1.1 Mission Statement Improve the living standard of the people by strengthening local government system, developing climate resilient rural and urban infrastructure and implementing socio-economic activities. 1.2 Major Functions 1.2.1 Manage all matters relating to local government and local government institutions; 1.2.2 Construct, maintain and manage Upazilla, union and village roads including the roads and bridges/culverts of towns and municipal areas; 1.2.3 Develop, maintain and manage growth centres and hats-bazaars connected via Upazilla, union and village roads; 1.2.4 Manage matters relating to safe drinking water; 1.2.5 Develop water supply, sanitation and sewerage facilities in climate risk vulnerable rural and urban areas; 1.2.6 Finance, evaluate and monitor local government institutions and offices/organizations under Local Government Division; 1.2.7 Develop, maintain and manage small-scale water resource infrastructures within the timeline determined by the government. 1.2.8 Enactment of Law, promulgation of rules and policies related to local government. -

Land Resource Appraisal of Bangladesh for Agricultural

BGD/81/035 Technical Report 3 Volume II LAND RESOURCES APPRAISAL OF BANGLADESH FOR AGRICULTURAL DEVELOPMENT REPORT 3 LAND RESOURCES DATA BASE VOLUME II SOIL, LANDFORM AND HYDROLOGICAL DATA BASE A /UNITED NATIONS DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMME FAo FOOD AND AGRICULTURE ORGANIZATION vJ OF THE UNITED NATIONS BGD/81/035 Technical Report 3 Volume II LAND RESOURCES APPRAISAL OF BANGLADESH FOR AGRICULTURALDEVELOPMENT REPORT 3 LAND RESOURCES DATA BASE VOLUME II SOIL, LANDFORM AND HYDROLOGICAL DATA BASE Report prepared for the Government of the People's Republic of Bangladesh by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations acting as executing agency for the United Nations Development Programme based on the work of H. Brammer Agricultural Development Adviser J. Antoine Data Base Management Expert and A.H. Kassam and H.T. van Velthuizen Land Resources and Agricultural Consultants UNITED NATIONS DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMME FOOD AND AGRICULTURE ORGANIZATION OF THE UNITED NATIONS Rome, 1988 The designations employed and the presentation of material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and AgricultureOrganization of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored ina retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopyingor otherwise, without the prior perrnission of (he copyright owner. Applications for such permission,with a statement of the purpose and extent of the reproduction, should be addressedto the Director, Publications Division, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Viadelle Terme di Caracarla, 00100 Home, Italy. -

Investigation on Anthrax in Bangladesh During the Outbreaks of 2011 and Definition of the Epidemiological Correlations

pathogens Article Investigation on Anthrax in Bangladesh during the Outbreaks of 2011 and Definition of the Epidemiological Correlations Domenico Galante 1 , Viviana Manzulli 1,* , Luigina Serrecchia 1, Pietro Di Taranto 2, Martin Hugh-Jones 3, M. Jahangir Hossain 4,5, Valeria Rondinone 1, Dora Cipolletta 1, Lorenzo Pace 1 , Michela Iatarola 1, Francesco Tolve 1, Angela Aceti 1, Elena Poppa 1 and Antonio Fasanella 1 1 Istituto Zooprofilattico Sperimentale of Puglia and Basilicata, Anthrax Reference Institute of Italy, 71121 Foggia, Italy; [email protected] (D.G.); [email protected] (L.S.); [email protected] (V.R.); [email protected] (D.C.); [email protected] (L.P.); [email protected] (M.I.); [email protected] (F.T.); [email protected] (A.A.); [email protected] (E.P.); [email protected] (A.F.) 2 Servizio Igiene degli Allevamenti e delle Produzioni Zootecniche—Asl 02 Abruzzo Lanciano—Vasto-Chieti, 66054 Vasto, Italy; [email protected] 3 Department of Environmental Sciences, Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge, LA 70803-5705, USA; [email protected] 4 International International Centre for Diarrheal Disease Research, Programme on Infectious Diseases & Vaccine Sciences, Health System & Infectious Disease Division, Bangladesh (ICDDR,B), 1212 Dhaka, Bangladesh; [email protected] 5 Medical Research Council Unit The Gambia at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, 273 Banjul, The Gambia * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +39-0881786330 Citation: Galante, D.; Manzulli, V.; Serrecchia, L.; Taranto, P.D.; Abstract: In 2011, in Bangladesh, 11 anthrax outbreaks occurred in six districts of the country. -

World Food Programme, Bangladesh Situation Report

World Food Programme, Bangladesh Situation Report (Kindly limit this report within 2 pages. First page focus on qualitative information and second page on figures) Reporting Sub Office: Jessore Hazard (Flood/Cyclone etc.): Flood Reporting Date: 08.08.07 Reporting Period: 6-7 August 2006 Overall Summary: (Overall synopsis of the situation combining qualitative and quantitative information, disaster trend deteriorating or improving, overall coordination etc.) • Overall situation in Rajbari, Faridpur, Shraitpur, Madariprur and Magura is deteriorating day by day new areas such as Barisal, Gopalganj inaundedted by flood water. • In Shariatpur 72%, Faridpur 53%, Madaripur 42%, Rajbari 27% and Magura 32% of the total areas severely affected by the flood where 29%, 30%, 51%, 52% and 37% of the population affected respectively. • Disaster control room opened in all district and upazila headquarters. District and Upazila disaster management committees are working efficiently and maintained liaison among the other partners. • The District Disaster Management Committee of Madaripur and Shariatpur have generated local fund for relief activities. This fund collected from different professional groups, elite persons and others. • Advisors of central Government already have visited in Rajbari and Faridpur district. Honorable President has planned to visit Shariatpur district today. Prevailing Situation: (Precise and focused description on what occurred, when occurred, how the event has negatively impacted the lives/livelihoods of the populations and WFP beneficiaries, coping capacity, crops, assets, cattle/poultry, infrastructure etc. Please also articulate gender related information i.e. special needs for the women etc.) • Prevailing flood situation created by heavy rainfall in mid-July and upstream water. Basically situation has been severely deteriorating since 1 August 2007. -

Project Completion Report

Local Government Engineering Department (LGED) Ministry of Local Government, Rural Development and Cooperatives People’s Republic of Bangladesh Special Assistance for Project Implementation on Small Scale Water Resources Development Project (Phase 2) Project Completion Report Main Report June 2018 Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) Nippon Koei Co., Ltd. BD JR 18-004 List of Reports MAIN REPORT ANNEXES: - ANNEX I JICA-2 Operational Guidelines Volume 1: Project Policy - ANNEX II JICA-2 Operational Guidelines Volume 2: New Development - ANNEX III JICA-2 Operational Guidelines Volume 3: Additional Development - ANNEX IV JICA-2 Operational Guidelines Volume 4: Flagship Development Bangladesh - Special Assistance for Project Implementation on Small Scale Water Resources Development Project (Phase-2) SUMMARY 1 Background and Objectives The Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) formulated the Small Scale Water Resources Development Project Phase-2 (hereinafter referred to as JICA-2). Since the new development concepts will be introduced to JICA-2, the Local Government Engineering Department (LGED) required JICA to execute the special assistance for project implementation (SAPI) for the smooth implementation of new development concepts under JICA-2. The objective of SAPI is to support the project management unit (PMU) established in the LGED for the preparation of operational guidelines of JICA-2. The expected outputs of this SAPI are as follows: Output 1: The operational guidelines of JICA-2 are prepared; Output 2: The first and second batches of subprojects under JICA-2 are selected; Output 3: Training manuals on organizing/strengthening water management cooperative association (WMCA) in JICA-2 are prepared; Output 4: The capacity of project management is improved and project implementation system is in place by conducting orientation and workshop; and Output 5: The local consultants engaged in JICA-2 are selected. -

Outbreak of Nipah Encephalitis in Greater Faridpur District Review

Faridpur Med. Coll. J. 2010;5(2):63-65 Review Article Outbreak Of Nipah Encephalitis In Greater Faridpur District MY Ali1, SA Fattah2, MM Islam3, MA Hossain4, SY Ali5 Abstract Nipah viral encephalitis is one of the fatal re-emerging infections especially in southeast Asia. After its outbreak in Malaysia and Singapore; repeated outbreaks occurred at western part of Bangladesh especially in Faridpur region. Besides, sporadic attacks appear to occur in the country throughout the year. Here two Nipah outbreaks in greater Faridpur district in 2003 and 2004 are described along with brief review on transmission of the virus. Where the history of illness among patients are very much in favour of man to man transmission. Moreover the death of an intern doctor from Nipah encephalitis who was involved in managing such patients in Faridpur Medical College Hospital strongly suggests man to man transmission of this virus. So, aim of this review article to make the health personnel and general people be aware about man to man transmission of virus, so that they can adapt personal protection equipment (PPE) for their protection against this deadly disease. Introduction Depending on the presentation and for surveillance study, cases are described as probable, suspected and Nipah virus is a member of the family paramyxo- confirmed cases. viridiae affecting human being & less frequently pigs. 1. Probable case: any person, dead or alive, who Nomenclature of this Nipah in Malaysia where developed- epidemic was seen1. After entry, the virus replicates at • Fever and headache the primary sites- lung and gut associated lymphoid • Neurological sign's (one or more of the isolated tissue. -

AGRICULTURE, LIVESTOCK and FISHERIES

Research in ISSN : P-2409-0603, E-2409-9325 AGRICULTURE, LIVESTOCK and FISHERIES An Open Access Peer Reviewed Journal Open Access Res. Agric. Livest. Fish. Research Article Vol. 3, No. 3, December 2016: 395-402 AGRICULTURAL WASTE MANAGEMENT PRACTICES IN TRISHAL UPAZILLA, MYMENSINGH Tangina Akhter1*, Md. Ali Ashraf2, Md. Monirul Hassan3 , Farzana Akhter4 and Azmira Nasrin Riza5 1&5Bangladesh Agricultural Development Corporation (BADC), Dhaka, Bangladesh; 2&3Department of Farm Structure and Environmental Engineering, Bangladesh Agricultural University, Mymensingh-2202, Bangladesh; 4Bangladesh Agricultural Research Institute (BARI), Gazipur, Bangladesh *Corresponding author: Tangina Akhter; E-mail: [email protected] ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Received A study was conducted to assess the present status of agricultural waste management by 13.11.2016 farmers in Trishal upazila of Mymensingh district, Bangladesh. During April to May 2015 and data were collected from the sample of 70 farmers and 5 farms. A structured interview Accepted schedule was used for collection of data. The study explored the relationship between the 13.12.2016 four selected type farming (independent variable) of farmers with their generation of agricultural waste (dependent variable). In this study the highest amount waste (straw and Online husk production) is closely related with the size of cropland. Straw production less than or 18 December 2016 equal 1000 kg is 36.62%, straw production less than or equal 10000 kg is 54.92%, straw production less than or equal 20000 kg is 5.63% and straw production less than or equal Key words 30000 is 2.81% and husk production less than or equal 1000 kg is 35.71%, husk production Waste, less than or equal 10000 kg is 55.71%, husk production less than or equal 15000 kg is 8.57%. -

An Exploratory Study on Farmer's Vernacular Knowledge About The

International Journal of Environmental & Agriculture Research (IJOEAR) ISSN:[2454-1850] [Vol-6, Issue-1, January- 2020] An exploratory study on farmer’s vernacular knowledge about the land characteristics, soil quality and crop suitability in Lower Ganga Flood Plain: Bangladesh Perspective Samsunnahar popy Dept. of ESD, Banga bandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman Science & Technology University, Gopalganj, Bangladesh Abstract— Local people and small scale farmer had a broad understanding of their land characteristics and soil quality to choose crop. Though Maximum farmers in our country are illiterate and little educated; they have no enough scientific knowledge about land type, soil quality and crop suitability. But they possess vast indigenous knowledge by living in a same environment for a long period of time. They have developed some strategies that helped them to attain a higher degree of satisfaction in farming. So therefore it is very important to explore the farmer’s vernacular knowledge about the land type, soil quality and crop suitability. To address this indigenous knowledge this study investigates the farmer’s vernacular knowledge about the land type, soil quality and crop suitability in Lower Ganga Flood Plain in Bangladesh. The information was collected from one Mouza in Nagarkanda upazila, Faridpur district Lower Ganga Flood Plain in Bangladesh. Qualitative and quantitative both data were used in this study. The data were collected from primary sources (such as questionnaire survey, FGD) and secondary data sources (such as books, journals, and published and unpublished research reports). Data were analyzed by exploratory statistics. Graphs and graph tables were created by MS excel. By analyzing the Field data it was investigated that farmers of the study area recognized four elevation levels of land; i).