Meta-Analysis of Benzodiazepine Use in the Treatment of Insomnia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Effects of Brotizolam, a New Thieno-Triazolo-Diazepine Derivative, on the Central Nervous System

In the present study, its actions on the central nervous system were investigated. Effects of Brotizolam, a New Thieno-Triazolo-Diazepine Derivative, on the Central Nervous System Kenjiro KIMISHIMA, Kyoko TANABE, Yukako KINOSHITA, Kooji TOKUYOSHI, Daisuke HOURI and Tatsuo KOBAYASHI Department of Pharmacology, Tottori University School of Medicine, Yonago 683, Japan Accepted August 24, 1984 Abstract-The effects of brotizolam, a new thieno-triazolo-diazepine derivative, on the central nervous system were analyzed in mice, rats and rabbits. Diazepam, estazolam and triazolam were used as control drugs. Brotizolam inhibited spon taneous motor activities; performances in the rotarod test, staircase test, and maximal electroshock seizure test; and pentetrazol or bemegride-induced convulsion. Moreover, catalepsy inducing action and potentiating effect on sleep elicited by pentobarbital or ethanol were observed. Following intraperitoneal or oral admin istration of brotizolam to rabbits with chronically implanted electrodes , the electro encephalographic profile in spontaneous EEG was characterized by slow waves with high amplitudes in the neocortex. The arousal responses by stimulation of the midbrain reticular formation and posterior hypothalamus were slightly inhibited, but the recruiting responses induced by stimulation of the diffuse thalamic projecting system were not inhibited, and seizure discharges induced by stimulation of the dorsal hippocampus were inhibited markedly. When motor activities and pente trazol-induced convulsions were observed as indices of tolerance for brotizolam, tolerance was not developed by repeated administration of brotizolam up to 14 days. These results suggested that brotizolam, a new thieno-triazolo-diazepine derivative, is judged to be a safer and stronger sleep inducer than diazepam and estazolam . Since the pioneering paper by Randall et et al. -

S1 Table. List of Medications Analyzed in Present Study Drug

S1 Table. List of medications analyzed in present study Drug class Drugs Propofol, ketamine, etomidate, Barbiturate (1) (thiopental) Benzodiazepines (28) (midazolam, lorazepam, clonazepam, diazepam, chlordiazepoxide, oxazepam, potassium Sedatives clorazepate, bromazepam, clobazam, alprazolam, pinazepam, (32 drugs) nordazepam, fludiazepam, ethyl loflazepate, etizolam, clotiazepam, tofisopam, flurazepam, flunitrazepam, estazolam, triazolam, lormetazepam, temazepam, brotizolam, quazepam, loprazolam, zopiclone, zolpidem) Fentanyl, alfentanil, sufentanil, remifentanil, morphine, Opioid analgesics hydromorphone, nicomorphine, oxycodone, tramadol, (10 drugs) pethidine Acetaminophen, Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (36) (celecoxib, polmacoxib, etoricoxib, nimesulide, aceclofenac, acemetacin, amfenac, cinnoxicam, dexibuprofen, diclofenac, emorfazone, Non-opioid analgesics etodolac, fenoprofen, flufenamic acid, flurbiprofen, ibuprofen, (44 drugs) ketoprofen, ketorolac, lornoxicam, loxoprofen, mefenamiate, meloxicam, nabumetone, naproxen, oxaprozin, piroxicam, pranoprofen, proglumetacin, sulindac, talniflumate, tenoxicam, tiaprofenic acid, zaltoprofen, morniflumate, pelubiprofen, indomethacin), Anticonvulsants (7) (gabapentin, pregabalin, lamotrigine, levetiracetam, carbamazepine, valproic acid, lacosamide) Vecuronium, rocuronium bromide, cisatracurium, atracurium, Neuromuscular hexafluronium, pipecuronium bromide, doxacurium chloride, blocking agents fazadinium bromide, mivacurium chloride, (12 drugs) pancuronium, gallamine, succinylcholine -

Drug Information Sheet("Kusuri-No-Shiori")

Drug Information Sheet("Kusuri-no-Shiori") Internal Published: 08/2015 The information on this sheet is based on approvals granted by the Japanese regulatory authority. Approval details may vary by country. Medicines have adverse reactions (risks) as well as efficacies (benefits). It is important to minimize adverse reactions and maximize efficacy. To obtain a better therapeutic response, patients should understand their medication and cooperate with the treatment. Brand name:BROTIZOLAM TABLETS 0.25mg 「OHARA」 Active ingredient:Brotizolam Dosage form:white tablet with split line on one side, diameter: 8.0 mm, thickness: 2.3 mm Print on wrapping:ブロチゾラム錠 0.25mg「オーハラ」, ブロチゾラム, 0.25mg, OH-54, Brotizolam 0.25mg「OHARA」 Effects of this medicine This medicine intensifies the effect of GABA (γ-aminobutyric acid), a typical inhibitory transmitter of central nervous system, and suppresses hypothalamic area and cerebral limbic system which control emotion. It consequently blocks unnecessary stimulation from the autonomic nervous system and shows central nervous system depressant effect including hypnotic/sedative/anti-anxiety effect. It is usually used to treat insomnia and for anesthetic premedication. Before using this medicine, be sure to tell your doctor and pharmacist ・If you have previously experienced any allergic reactions (itch, rash, etc.) to any medicines. If you have glaucoma, myasthenia gravis or respiratory disability. ・If you are pregnant or breastfeeding. ・If you are taking any other medicinal products. (Some medicines may interact to enhance or diminish medicinal effects. Beware of over-the-counter medicines and dietary supplements as well as other prescription medicines.) Dosing schedule (How to take this medicine) ・Your dosing schedule prescribed by your doctor is<< to be written by a healthcare professional>> ・For insomnia: In general, for adults, take 1 tablet (0.25 mg of the active ingredient) at a time right before bedtime. -

Antioxidative and Neuroprotective Effects of Leea Macrophylla

Ferdousy et al. Clinical Phytoscience (2016) 2:17 DOI 10.1186/s40816-016-0031-6 ORIGINAL CONTRIBUTION Open Access Antioxidative and neuroprotective effects of Leea macrophylla methanol root extracts on diazepam-induced memory impairment in amnesic Wistar albino rat Sakia Ferdousy1, Md Atiar Rahman1*, Md Mamun Al-Amin2, Jannatul Aklima1 and J. M. Kamirul Hasan Chowdhury1 Abstract Background: A neurological disorder is becoming one of the major health problems worldwide. Synthetic drugs for neurological disorders often produce unwanted effects while traditional plant- derived drugs offer a unique strategy in combating the neurological diseases. This study investigated how the antioxidative properties of Leea macrophylla root extracts integratively help as neuroprotective and antiamnesic in animal model. Methods: Leea macrophylla root methanol extract (LM) was assessed by open field test, hole cross test, elevated plus maze test and thiopental sodium induced sleeping time test for screening neuropharmacological effect on Wistar albino rats using the LM at 100 & 200 mg/kg body weight. Antiamnesic effect of LM was studied on diazepam induced anterograde amnesia in Wistar albino rats. Morris water maze test was performed to evaluate whether the learning and memory of rats are impaired by amnesia produced by diazepam. The antioxidative enzymes superoxide dismutase, catalase, glutathione peroxidase and oxidative biomarkers malondialdehyde, nitric oxide, advanced oxidation protein product from the hippocampus of decapitated animals were measured to assess the antioxidative potential of the extract. Results: LM was found to show significant (p <0.05) reduction in locomotor activity and increase in the duration of sleeping of animals. Morris water maze test showed that animals treated with LM significantly (p <0.05) decreased the mean escape latency compared to animals in diazepam group. -

A Review of the Evidence of Use and Harms of Novel Benzodiazepines

ACMD Advisory Council on the Misuse of Drugs Novel Benzodiazepines A review of the evidence of use and harms of Novel Benzodiazepines April 2020 1 Contents 1. Introduction ................................................................................................................................. 4 2. Legal control of benzodiazepines .......................................................................................... 4 3. Benzodiazepine chemistry and pharmacology .................................................................. 6 4. Benzodiazepine misuse............................................................................................................ 7 Benzodiazepine use with opioids ................................................................................................... 9 Social harms of benzodiazepine use .......................................................................................... 10 Suicide ............................................................................................................................................. 11 5. Prevalence and harm summaries of Novel Benzodiazepines ...................................... 11 1. Flualprazolam ......................................................................................................................... 11 2. Norfludiazepam ....................................................................................................................... 13 3. Flunitrazolam .......................................................................................................................... -

Centre for Reviews and Dissemination

Tolerance and rebound insomnia with rapidly eliminated hypnotics: a meta-analysis of sleep laboratory studies Soldatos C R, Dikeos D G, Whitehead A Authors' objectives To determine whether there are differences in initial efficacy, development of tolerance and occurrence of rebound insomnia between rapidly eliminated hypnotics (brotizolam, midazolam, triazolam, zolpidem and zopiclone). Searching MEDLINE was searched from 1966 to April 1997 using the generic names of the drugs as keywords, i.e. 'brotizolam', 'midazolam', 'triazolam', 'zolpidem' and 'zopiclone'. Additional references were obtained by examining the bibliographies of retrieved papers, and by contacting pharmaceutical manufacturers. Abstracts of all available publications were scanned visually to identify sleep laboratory studies. Study selection Study designs of evaluations included in the review The following study designs were included: randomised placebo-controlled parallel group or crossover studies, with or without placebo baseline; single group studies with placebo baseline (i.e. before-and-after studies). Studies were excluded for the following reasons: unconventional timing of sleep, or conditions or procedures of monitoring that may interfere with sleep; nonstandard sleep recording and/or scoring procedures; no placebo control; participants with concurrent medical or psychiatric disorders; inadequate or no washout-period; inadequate documentation of blindness and/or randomisation; no adaptation night in a single group study; no data relevant for the present study; unconventional placebo comparator. All studies had to be double-blind, i.e. even for single group studies, patient and assessor had to be blinded to actual treatment on days of assessment. Specific interventions included in the review Brotizolam, midazolam, triazolam, zolpidem and zopiclone; all were compared to placebo. -

Clinical Practice Guideline for the Pharmacologic Treatment of Chronic Insomnia in Adults: an American Academy of Sleep Medicine Clinical Practice Guideline Michael J

pii: jc-00382-16 http://dx.doi.org/10.5664/jcsm.6470 SPECIAL ARTICLES Clinical Practice Guideline for the Pharmacologic Treatment of Chronic Insomnia in Adults: An American Academy of Sleep Medicine Clinical Practice Guideline Michael J. Sateia, MD1; Daniel J. Buysse, MD2; Andrew D. Krystal, MD, MS3; David N. Neubauer, MD4; Jonathan L. Heald, MA5 1Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth, Hanover, NH; 2University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, Pittsburgh, PA; 3University of California, San Francisco, San Francisco, CA; 4Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD; 5American Academy of Sleep Medicine, Darien, IL Introduction: The purpose of this guideline is to establish clinical practice recommendations for the pharmacologic treatment of chronic insomnia in adults, when such treatment is clinically indicated. Unlike previous meta-analyses, which focused on broad classes of drugs, this guideline focuses on individual drugs commonly used to treat insomnia. It includes drugs that are FDA-approved for the treatment of insomnia, as well as several drugs commonly used to treat insomnia without an FDA indication for this condition. This guideline should be used in conjunction with other AASM guidelines on the evaluation and treatment of chronic insomnia in adults. Methods: The American Academy of Sleep Medicine commissioned a task force of four experts in sleep medicine. A systematic review was conducted to identify randomized controlled trials, and the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) process was used to assess the evidence. The task force developed recommendations and assigned strengths based on the quality of evidence, the balance of benefits and harms, and patient values and preferences. -

Ensuring Adequate Access for Medical and Scientific Purposes

INTERNATIONAL NARCOTICS CONTROL BOARD Availability of Internationally Controlled Drugs Controlled Internationally of Availability Availability of Internationally Controlled Drugs: Ensuring Adequate Access for Medical and Scientific Purposes Indispensable, adequately available and not unduly restricted UNITED NATIONS Reports published by the International Narcotics Control Board in 2015 TheReport of the International Narcotics Control Board for 2015 (E/INCB/2015/1) is supple- mented by the following reports: Availability of Internationally Controlled Drugs: Ensuring Adequate Access for Medical and Scientific Purposes. Indispensable, adequately available and not unduly restricted (E/INCB/2015/1/Supp.1) Narcotic Drugs: Estimated World Requirements for 2016—Statistics for 2014 (E/INCB/2015/2) Psychotropic Substances: Statistics for 2014—Assessments of Annual Medical and Scientific Requirements for Substances in Schedules II, III and IV of the Convention on Psychotropic Substances of 1971 (E/INCB/2015/3) Precursors and Chemicals Frequently Used in the Illicit Manufacture of Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances: Report of the International Narcotics Control Board for 2014 on the Implementation of Article 12 of the United Nations Convention against Illicit Traffic in Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances of 1988 (E/INCB/2015/4) The updated lists of substances under international control, comprising narcotic drugs, psychotropic substances and substances frequently used in the illicit manufacture of narcotic drugs and psychotropic substances, are contained in the latest editions of the annexes to the statistical forms (“Yellow List”, “Green List” and “Red List”), which are also issued by the Board. Contacting the International Narcotics Control Board The secretariat of the Board may be reached at the following address: Vienna International Centre Room E-1339 P.O. -

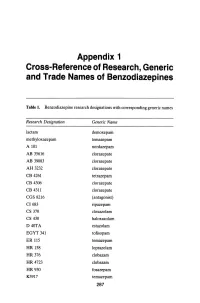

Appendix 1 Cross-Reference of Research, Generic and Trade Names of Benzodiazepines

Appendix 1 Cross-Reference of Research, Generic and Trade Names of Benzodiazepines Table 1. Benzodiazepine research designations with corresponding generic names Research Designation Generic Name lactam demoxepam methyloxazepam temazepam A 101 nordazepam AB 35616 clorazepate AB 39083 clorazepate AH 3232 clorazepate CB 4261 tetrazepam CB 4306 clorazepate CB 4311 clorazepate CGS 8216 (antagonist) CI683 ripazepam CS 370 cloxazolam CS 430 haloxazolam D40TA estazolam EGYT 341 tofisopam ER 115 temazepam HR 158 loprazolam HR376 clobazam HR 4723 clobazam HR930 fosazepam K3917 temazepam 287 THE BENZODIAZEPINES Research Designation Generic Name LA 111 diazepam LM 2717 clobazam ORF 8063 triflubazam Ro 4-5360 nitrazepam Ro 5-0690 chlordiazepoxide Ro 5-0883 desmethy1chlordiazepoxide Ro 5-2092 demoxepam Ro 5-2180 desmethyldiazepam Ro 5-2807 diazepam Ro 5-2925 desmethylmedazepam Ro 5-3059 nitrazepam Ro 5-3350 bromazepam Ro 5-3438 fludiazepam Ro 5-4023 clonazepam Ro 5-4200 flunitrazepam Ro 5-4556 medazepam Ro 5-5345 temazepam Ro 5-6789 oxazepam Ro 5-6901 flurazepam Ro 15-1788 (antagonist) Ro 21-3981 midazolam RU 31158 loprazolam S 1530 nimetazepam SAH 1123 isoquinazepam SAH 47603 temazepam SB 5833 camazepam SCH 12041 halazepam SCH 16134 quazepam U 28774 ketazolam U 31889 alprazolam U 33030 triazolam W4020 prazepam We 352 triflubazam 288 RESEARCH, GENERIC AND TRADE NAMES Research Designation Generic Name We 941 brotizolam Wy 2917 temazepam Wy 3467 diazepam Wy 3498 oxazepam Wy 3917 temazepam Wy 4036 lorazepam Wy 4082 lormetazepam Wy 4426 oxazepam Y 6047 -

Wo 2009/120182 A2

(12) INTERNATIONALAPPLICATION PUBLISHED UNDER THE PATENT COOPERATION TREATY (PCT) (19) World Intellectual Property Organization International Bureau (10) International Publication Number (43) International Publication Date 1 October 2009 (01.10.2009) WO 2009/120182 A2 (51) International Patent Classification: AO, AT, AU, AZ, BA, BB, BG, BH, BR, BW, BY, BZ, A61K 47/34 (2006.01) CA, CH, CN, CO, CR, CU, CZ, DE, DK, DM, DO, DZ, EC, EE, EG, ES, FI, GB, GD, GE, GH, GM, GT, HN, (21) International Application Number: HR, HU, ID, IL, IN, IS, JP, KE, KG, KM, KN, KP, KR, PCT/US2008/013816 KZ, LA, LC, LK, LR, LS, LT, LU, LY, MA, MD, ME, (22) International Filing Date: MG, MK, MN, MW, MX, MY, MZ, NA, NG, NI, NO, 18 December 2008 (18.12.2008) NZ, OM, PG, PH, PL, PT, RO, RS, RU, SC, SD, SE, SG, SK, SL, SM, ST, SV, SY, TJ, TM, TN, TR, TT, TZ, UA, (25) Filing Language: English UG, UZ, VC, VN, ZA, ZM, ZW. (26) Publication Language: English (84) Designated States (unless otherwise indicated, for every (30) Priority Data: kind of regional protection available): ARIPO (BW, GH, 61/015,365 20 December 2007 (20.12.2007) US GM, KE, LS, MW, MZ, NA, SD, SL, SZ, TZ, UG, ZM, 12/262,986 31 October 2008 (3 1.10.2008) US ZW), Eurasian (AM, AZ, BY, KG, KZ, MD, RU, TJ, TM), European (AT, BE, BG, CH, CY, CZ, DE, DK, EE, (71) Applicant: EASTMAN CHEMICAL COMPANY [US/ ES, FI, FR, GB, GR, HR, HU, IE, IS, IT, LT, LU, LV, US]; 200 South Wilcox Drive, Kingsport, TN 37660 MC, MT, NL, NO, PL, PT, RO, SE, SI, SK, TR), OAPI (US). -

Drug/Substance Trade Name(S)

A B C D E F G H I J K 1 Drug/Substance Trade Name(s) Drug Class Existing Penalty Class Special Notation T1:Doping/Endangerment Level T2: Mismanagement Level Comments Methylenedioxypyrovalerone is a stimulant of the cathinone class which acts as a 3,4-methylenedioxypyprovaleroneMDPV, “bath salts” norepinephrine-dopamine reuptake inhibitor. It was first developed in the 1960s by a team at 1 A Yes A A 2 Boehringer Ingelheim. No 3 Alfentanil Alfenta Narcotic used to control pain and keep patients asleep during surgery. 1 A Yes A No A Aminoxafen, Aminorex is a weight loss stimulant drug. It was withdrawn from the market after it was found Aminorex Aminoxaphen, Apiquel, to cause pulmonary hypertension. 1 A Yes A A 4 McN-742, Menocil No Amphetamine is a potent central nervous system stimulant that is used in the treatment of Amphetamine Speed, Upper 1 A Yes A A 5 attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, narcolepsy, and obesity. No Anileridine is a synthetic analgesic drug and is a member of the piperidine class of analgesic Anileridine Leritine 1 A Yes A A 6 agents developed by Merck & Co. in the 1950s. No Dopamine promoter used to treat loss of muscle movement control caused by Parkinson's Apomorphine Apokyn, Ixense 1 A Yes A A 7 disease. No Recreational drug with euphoriant and stimulant properties. The effects produced by BZP are comparable to those produced by amphetamine. It is often claimed that BZP was originally Benzylpiperazine BZP 1 A Yes A A synthesized as a potential antihelminthic (anti-parasitic) agent for use in farm animals. -

Pharmacological Drugs Inducing Ototoxicity, Vestibular Symptoms and Tinnitus: a Reasoned and Updated Guide

European Review for Medical and Pharmacological Sciences 2011; 15: 601-636 Pharmacological drugs inducing ototoxicity, vestibular symptoms and tinnitus: a reasoned and updated guide G. CIANFRONE1, D. PENTANGELO1, F. CIANFRONE2, F. MAZZEI1, R. TURCHETTA1, M.P. ORLANDO1, G. ALTISSIMI1 1Department of Otolaryngology, Audiology and Phoniatrics, “Umberto I” University Hospital, Sapienza University, Rome (Italy); 2Institute of Otorhinolaryngology, School of Medicine, Catholic University of the Sacred Heart, Rome (Italy) Abstract. – The present work on drug-in- Introduction duced ototoxicity, tinnitus and vertigo repre- sents the update and revision of a previous The panorama of the pharmacological origin guide to adverse drug reactions for italian physi- iatrogenic noxae able to induce either harmful cians (2005). The panorama of drug-induced side effects causing ototoxicity or symptoms ototoxic effects or just a symptomatology like tin- such as tinnitus or dizziness and vertigo has en- nitus or balance disturbances, without any harm- larged in recent years, thanks to a better knowl- ful consequence, has widened in the last few edge and a more specific attention of pharma- years. The reason for this is the progress of scien- ceutical firms and drug-control institutions. In tific knowledge, the increased awareness of the daily clinical practice, there is a need for the pharmaceutical companies and of the institutions, family physician and the ENT specialist or audi- ologist (also in consideration of the possible which supervise pharmaceutical production. medico-legal implications) to focus the attention Only through continuous updating and experi- on the possible risk of otological side effects. ence sharing it’s possible to offer patients the This would allow a clinical risk-benefit evalua- certainty of receiving the treatment that is appro- tion, weighing the possible clinical advantage in priate, safe and effective and based upon the their field of competence against possible oto- most credited clinical studies.