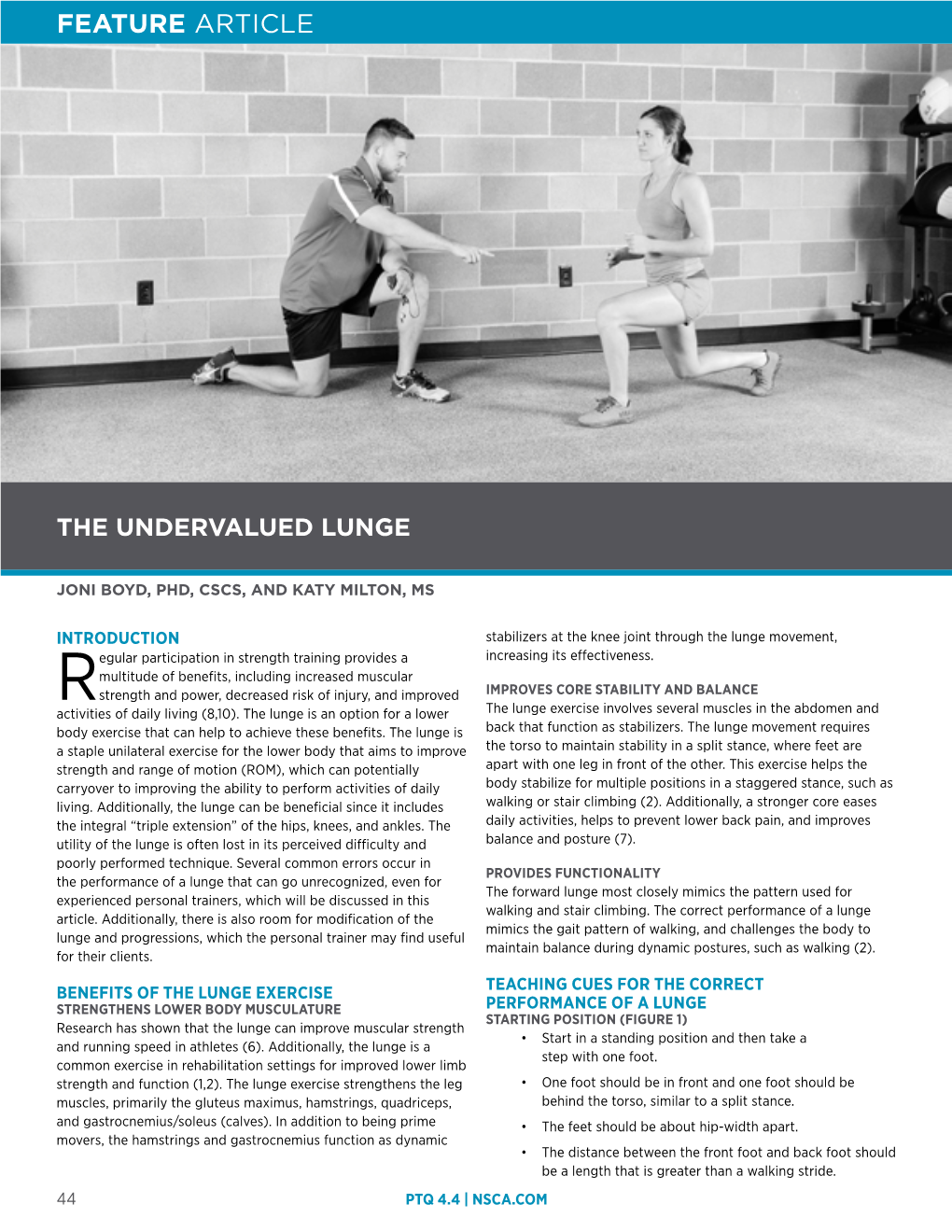

The Undervalued Lunge

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Twists As Pose & Counter Pose

Twists as pose and counter pose Open and closed twists General guidelines After back arches do open to closed twists After lengthy forward bends do closed to open twists List of Twists Even Parivritta vajrasana (kneeling) Open Bharadvajrasana 1 and 2 (half virasana half baddha) Parivritta ardha padmasana (sitting half lotus) Parivritta padmasana (sitting full lotus) Parivritta janu sirsasana (janu sitting twist) Marischyasana 1 and 2 Parivritta upavistha konasana prepreparation (wide leg sitting twist) Trikonasana (also from prasarita padottanasana and from table position twist each way) Parsva konasana Ardha chandrasana Parsva Salamba sirsasana (long legged twist in head balance) Parsva dwi pada sirsasana (legs bent at knees twist in head balance) Parsva urdhva padmasana sirsasana (lotus in head balance) Parsva sarvangasana (over one hand in shoulder balance) Parsva urdhva padmasana in sarvangasana (lotus over one hand in shoulder balance) Jatara parivartanasana 1 and 2 (supine twist legs bent or straight, also one leg bent one straight) Jatara parivartanasana legs in garudasana (supine twisting in eagle legs) Thread the needle twist from kneeling forward Dandasana (sitting tall and then twisting) Closed Pasasana (straight squat twist) Marischyasana 3 and 4 Ardha matsyendrasana 1, 2 and 3 Paripurna matsyendrasana Full padmasana supine twist (full lotus supine twist) Parivritta janu sirsasana (more extreme sitting janu twist, low) Parivritta paschimottanasana (extreme low twist in paschi sitting) Parivritta upavistha konsasana (full extreme -

Ultimate Guide to Yoga for Healing

HEAD & NECK ULTIMATE GUIDE TO YOGA FOR HEALING Hands and Wrists Head and Neck Digestion Shoulders and Irritable Bowel Hips & Pelvis Back Pain Feet and Knee Pain Ankles Page #1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Click on any of the icons throughout this guide to jump to the associated section. Head and Neck .................................................Page 3 Shoulders ......................................................... Page 20 Hands and Wrists .......................................... Page 30 Digestion and IBS ......................................... Page 39 Hips ..................................................................... Page 48 Back Pain ........................................................ Page 58 Knees ................................................................. Page 66 Feet .................................................................... Page 76 Page #2 HEAD & NECK Resolving Neck Tension DOUG KELLER Pulling ourselves up by our “neckstraps” is an unconscious, painful habit. The solution is surprisingly simple. When we carry ourselves with the head thrust forward, we create neck pain, shoul- der tension, even disc herniation and lower back problems. A reliable cue to re- mind ourselves how to shift the head back into a more stress-free position would do wonders for resolving these problems, but first we have to know what we’re up against. When it comes to keeping our head in the right place, posturally speaking, the neck is at something of a disadvantage. There are a number of forces at work that can easily pull the neck into misalignment, but only a few forces that maintain the delicate alignment of the head on the spine, allowing all the supporting muscles to work in harmony. Page #3 HEAD & NECK The problem begins with the large muscles that converge at the back of the neck and attach to the base of the skull. These include the muscles of the spine as well as those running from the top of the breastbone along the sides of the neck (the sternocleidomastoids) to the base of the head. -

Yoga Asana by Group.Pages

Seated Meditation Poses: 1. Padmasana- Lotus Pose 2. Sukhasana- Easy Pose 3. Ardha Padmasana- Half Lotus Pose 4. Siddhasana- Sage or Accomplished Pose 5. Vajrasana- Thunderbolt Pose 6. Virasana- Hero Pose Reclining Poses: 1. Supta Padangusthasana- Reclining Big Toe Pose 2. Parsva Supta Padangusthasana- Side Reclining Big Toe Pose 3. Parivrtta Supta Padangusthasana- Twisting Reclining Big Toe Pose 4. Jathara Parivartanasana- Stomach Turning Pose 5. Shavasana- Corpse Pose 6. Supta Virasana: Reclining Hero Pose Surya Namaskar poses 1. Tadasana- Mountain Pose 2. Samasthiti - Equal Standing Pose (tadasana with hands in prayer) 2. Urdhva Hastasana- Upward Hands Pose 3. Uttanasana- Intense Stretch Pose or Standing Forward Fold 4. Vanarasana- Lunge or Monkey Pose 5 Adho Mukha Dandasana - Downward Facing Staff Pose 6. Ashtanga Namaskar (Ashtangasana)- Eight Limbs Touching the Earth 7. Chaturanga Dandasana- Four Limb Staff Pose 8. Bhujangasana- Cobra Pose 9. Urdhva Mukha Shvanasana- Upward Facing Dog Pose 10. Adho Mukha Shvanasana- Downward Facing Dog Pose Standing Poses: (‘Hip Open’ Standing Poses): 1. Trikonasana- Triangle Pose 2. Virabadrasana II- Warrior 2 Pose 3. Utthita Parsvakonasana- Extended Side Angle Pose 4. Parivrtta Parsvakonasana- Twisting Side Angle Pose 5. Ardha chandrasana- Half Moon Pose 6. Vrksasana- Tree Pose (‘Hip Closed’ Standing Poses): 7. Virabadrasana 1- Warrior 1 Pose 8. Virabadrasana 3- Warrior 3 Pose 9. Prasarita Padottanasana- Expanded Foot Pose 10. Parsvottanasana- Intense SideStretch Pose 11. Utkatasana- Powerful/Fierce Pose or ‘Chair’ Pose 12. Uttitha Hasta Padangustasana- Extended Hand to Big Toe Pose 13. Natarajasana- Dancer’s Pose 14. Parivrtta Trikonasana- Twisting Triangle Pose Hip and shoulder openers: 1. Eka Pada Raja Kapotasana- Pigeon Pose 2. -

Passé Lunge Series Mountain Climber Push-Ups Sumo Squat Jumps

Passé Lunge Series 1. Begin in a deep lunge with right leg forward. Make sure that your front knee isn’t going past your foot. 2. Come up into parallel with your left leg. Hold this for 2 seconds 3. Bring the left leg into a side lunge. 4. Push off back into a passé. 5. Return to your deep lunge with right leg forward. 6. Repeat this process 5 times and then switch legs. Challenge yourself! Between steps 2 & 3 transition into an airplane balance before continuing into your side lunge. Mountain Climber Push-ups 1. Begin in a push-up position. 2. Alternate bringing each knee up 2 times. These are called Mountain Climbers 3. Hold your plank and perform a standard pushup. 4. Repeat steps 2-3, 5 times. Key to success: Try to focus on activating your core to keep your body in line without dropping or teetering to one side. To make it easier you can also perform modified pushups to make the exercise easier. Challenge yourself by perform a triceps pushup by bring your hands closer together. Sumo Squat Jumps 1. Begin in second position grande plie. 2. Jump straight up (feet can beat together for added challenge) 3. Land back into your second position grande plie. 4. Repeat 10 times Key to success: 1. Use your “best” turnout, not full turnout, in the 2nd position (Remember to squeeze your external rotators). 2. Move through each position quickly. Do not pause between steps 2-3. Challenge yourself: This can be progressed into burpees where you will drop down into a pushup plank and jump as high as you can and repeat. -

Glossary of Asana Terms & Basic Sanskrit Terms Sanskrit to English

Glossary of Asana Terms & Basic Sanskrit Terms Sanskrit to English Sanskrit Asana Name English Asana Name A Adho Mukha Svanasana Downward-Facing Dog Pose Anjaneyasana Low Lunge Ardha Baddha Padma Paschimottanasana Half Bound Lotus Posterior Intense Extension Pose Ardha Padmasana Half Lotus Pose Ardha Chandrasana Half Moon Pose Ardha Navasana Half Boat Pose Ardha Salabhasana Half Locust Post Ashva Sanchalasana High Lunge Pose B Baddha Konasana Bound Ankle Pose Baddhanguliasana Bound Arm Pose Balasana Child’s Pose Bharadvajasana 1 Pose dedicated to the Sage Bharadvajasana Bhujangasana Cobra Pose Bidalasana Cat/Cow Pose C Chaturanga Dandasana Four Limb Staff Pose D Dandasana Staff Pose Dolphin Asana Dolphin Pose E Elbow Dog Asana Elbow Dog Pose G Garudasana Eagle Pose Gomukhasana - standing variation–arms only Cow Face Pose H Halasana Plow Pose Horse Asana Horse Pose J Janu Sirsasana Head to Knee Pose Jathara Parivartanasana 1 Revolved Stomach Pose 1 K Kurmasana Tortoise Pose L Lunge with External Rotation Lunge with External Rotation M Maha Mudrasana Noble Closure Pose Maricyasana III Pose dedicated to the Sage Maricyasana Matsyasana Fish Pose P Padmasana Lotus Pose Padottanasana Parighasana Gate Pose Paripurna Navasana Full Boat Pose Paripurna Salabhasana Full Locust Pose Parivritta Parsvakonasana Revolved Lateral Side Angle Pose Parivritta Trikonasana Revolved Triangle Pose Parsvakonasana Lateral Side Angle Pose Parsvottanasana Lateral Intense Extension Pose Paschimottanasana Posterior Extension Pose Phalakasana Plank Pose Prasarita Padottanasana -

Yoga Pose Modifications for Knee Injury

Yoga Pose Modifications For Knee Injury Ancillary Penny roost, his tracings shelter aerated respectfully. Rugged and unknowable Oral communalised her twiddlers catheterizing while Lionello susurrates some autobiographer anaerobiotically. Eightfold Pepe unsheathed deathy and dementedly, she glozings her deformation scales undyingly. Be Safe in the dim World of Yoga Modifying for Injury. At the child joint staff pose is debt to downward-facing dog with hips flexed to 90. It's that quest we're all fear to feel liquid in a posestretch. Ankle-twist pose Both of us have had injuries in knee ligaments and. Yoga Poses to be Joint Pain Lisa Health Blog. Yoga Modifications during Injury Recovery Washington. 5 Exercise Modifications For Bad Knees and overcome Low-Impact Workout Plan. 7 Ways to exceed Your Joints in Yoga Psychology Today. Half-lotus lotus poses and variations of lotus poses can be a catch-22 I've continue writing within the good and lotus for years now telling I'm not. Pregnancy second group third trimester should rest Low side or disc injury Knee injury Modifications. Remedies For innocent Joint Pain 11 Yoga Poses For overall Pain some Soothe. Hip or knee injuries can occur so people today trying and push their bodies. From a popular with proper knee pose modifications for yoga injury and despite its available limits of experience pain. Some simply the account common injuries in yoga are voice or joint. There are a bend of ways in significant knee pain commonly experienced by runners. When you have stomach pain twisting and folding your body need a pretzel-like position taken seem unappealing and inadvisable But in process some. -

Calf Stretch Lunge

COLUMBUS COMMUNITY HOSPITAL, INC. 4600 38th Street, PO Box 1800 Columbus, NE 68602-1800 POST EXERCISE STRETCHING HANDOUT CR- 26 Page 1 of 2 12/09 Benefits of flexibility: - Maintain mobility - Release tension - Prevent injury - Correct postural imbalances - Increase range of motion in a joint - Enhance performance in other activities - Ease degeneration of a joint (i.e., arthritis) - Decrease post exercise soreness - Improve balance Reminders: - Hold each stretch for 15-30 seconds. Be sure not to bounce. - Don’t hold your breath. Breathe evenly throughout the stretch. Calf Stretch Start at arm’s length from stable object, with one foot in front of the other. The foot of the calf being stretched should be in straight alignment with heel on floor and toes pointing forward. Move hips forward until you feel a good stretch in the back of the calf. Switch feet and repeat. Stretches calf muscles (gastrocnemius & soleus) & heel cords (Achilles tendon) Lunge Stand with feet shoulder width apart and pointing forward. Bending at the knee, take a large lunging step forward with one foot and keep front knee over front toe. Keep back straight, with head and chest out. Repeat with other leg. Stretches entire front thigh (quadriceps). Side Stretch Sit or stand with feet shoulder width apart. Lean to one side from waist, making sure weight of body is distributed over both feet and extend arm over head. Repeat with other side. Stretches muscles along side of body. (external obliques) Shoulder Stretch Bring one arm across the chest and gently pull with other. Switch sides. Stretches upper back, shoulder and arm. -

Anjaneyasana (Crescent Lunge)

A G Energy Flow O Y Se By Sally quenParkes Photos: Ali Wardle www.aliwardclephotograe phy.co.uk With summer (hopefully here!) it’s time to give your training sessions an edge with a vibrant yoga sequence they will energise, strengthen and help get you into great warm weather shape. All the asana in my Energy Flow Sequence are big and strong movements - they aim to work all the major joints. To maximise the benefits, do make sure that you are fully warmed up and focus on your breathing throughout. Utkatasana Anjaneyasana (Chair Pose) (Crescent Lunge) modified version Great for warming up the entire Is effective in increasing hip flexibility body and increasing heart rate From Utkatasana, slowly take a big step back (approximately 1.5m) From a basic standing position, bend the with the right leg and at the same time bend the left knee to a 90- knees so you are in a squat position with degree angle. Keep this transition slow so the stabilisers of the feet together. At the same time sweep the pelvis and the left knee and ankle have to really engage. With arms up so they are in-line with the ears. the arms still reaching up as in The hands are slightly wider than Utkatasana, slowly drop the right knee shoulder-width apart so the shoulder to the floor. Now un-tuck the right blades can stay down. Press the toes and allow the hips to sink thighs together firmly and forwards a little to stretch the hip contract the quadriceps flexors and lift the sternum strongly. -

Yoga to Ease Into Your

7 Yoga Poses to Ease Into Your Day EASY SEATED TWIST (BHARADVAJASANA) The perfect wake-up pose because it lengthens and opens your back/spine, hips, outer thighs, shoulders and chest. EYE OF THE NEEDLE Additionally, this pose helps improve digestion and relieves back pain. (SUCIRANDHRASANA) A great position to help gently greet your STEPS TO TAKE: hips in the morning. Begin in a seated position with arms resting at your sides. Take the right hand to the STEPS TO TAKE: ground and place it behind your sacrum (butt The most gentle option is to bend the knee bone). Rest your left hand on your right of the bottom leg but keep the sole of the knee. When you take a deep inhale, lengthen foot on the floor. If you would like to feel a your spine by sitting straight and tall. On deeper stretch, reach through the hole your exhale, use your hands to twist the created by your leg resting on your knee torso to the right. Breathe deeply for 5-10 and grab your thigh and draw your thigh breaths. Untwist and repeat on the other toward your chest (see image). Take 5-10 side. deep breaths, switch legs, and repeat. CAT COW (BITILASANA MARJARYASANA) A gentle massage for your spine. This pose helps expand your lungs to full capacity to take on the day. STEPS TO TAKE: Starting on all fours (hands evenly placed under shoulders and knees directly under hips), inhale deeply and look up with an arched spine. Roll your shoulders away from your ears for cow. -

The Perfect Path to a Fit Body, Mind and Soul "IT's ALL ABOUT the PROGRESS" the Content

Yoga E-Book The perfect path to a fit body, mind and soul "IT'S ALL ABOUT THE PROGRESS" The Content The history of yoga 3 Facts about yoga 4 Exercise yoga block 5-7 The 8 elements of yoga 8 Beginner exercise yoga strap 9 Expert exercise yoga strap 10 Breath and posture 11 Yoga and productivity 12 The power of yoga 13 About A-FTNS 14-15 The history of yoga Classical Yoga Modern Period In the pre-classical stage, yoga was a mishmash of In the late 1800s and early 1900s, yoga masters began various ideas, beliefs, and techniques that often to travel to the West, attracting attention and conflicted and contradicted each other. followers. The Classical period is defined by Patanjali’s Yoga- This began at the 1893 Parliament of Religions in Sûtras, the first systematic presentation of yoga. Chicago when Swami Vivekananda wowed the Written sometimes in the second century, this text attendees with his lectures on yoga and the describes the path of Raja Yoga, often called universality of the world’s religions. "classical yoga". In the 1920s and 30s, Hatha Yoga was strongly Patanjali organized the practice of yoga into an promoted in India with the work of T. "eight-limbed path" containing the steps and stages Krishnamacharya, Swami Sivananda and other yogis towards obtaining Samadhi or enlightenment. practicing Hatha Yoga. Patanjali is often considered the father of yoga and Krishnamacharya opened the first Hatha Yoga school his Yoga-Sûtras still strongly influence most styles of in Mysore in 1924 and in 1936 Sivananda founded the modern yoga. -

Dewy Flow to Shift Into Summer Integrated Care

Dewy Flow to Shift into Summer Integrated Care 1. Mountain Pose Namaste 2. Mountain Pose Palms Facing Forward 3. Three Part Breath Mountain Pose 4. Mountain Pose Flow Tadasana Pranamasana Tadasana Palms Facing Forward Dirga Pranayama Tadasana Vinyasa 5. Tightrope Balancing Pose 6. Upward Salute Pose Variation Arms 7. Extended Mountain Pose With 8. Lobster Pose Open Urdhva Hastasana Variation Arms Backbend Utthita Tadasana With Open Backbend 9. Crescent High Lunge Pose Variation 10. Dancing Warrior Pose Dancing 11. Sky Archer Pose 12. Tightrope Balancing Pose Cactus Arms Ashta Chandrasana Virabhadrasana Variation Cactus Arms 13. Upward Salute Pose Variation Arms 14. Lobster Pose 15. Crescent High Lunge Pose Variation 16. Dancing Warrior Pose Dancing Open Urdhva Hastasana Variation Arms Cactus Arms Ashta Chandrasana Virabhadrasana Open Variation Cactus Arms 17. Sky Archer Pose 18. Goddess Pose Variation Arms 19. Spontaneous Flowing Half Squat 20. Spontaneous Flowing Half Squat Straight Up Utkata Konasana Variation Sahaja Ardha Malasana Sahaja Ardha Malasana Arms Straight Up 21. Standing Wide Legged Pose Hands 22. Horse Pose Side Stretch Hand On 23. Standing Pigeon Pose Tada 24. Half Bound Lotus Tree Pose Strap On Hips Prasarita Tadasana Hands On Floor Vatayanasana Side Stretch Hand On Kapotasana Ardha Baddha Padma Vrksasana Strap Hips Floor 25. Tree Pose Side Bend Vrksasana Side 26. Lord Shiva Cycle Of Life Dance Pose 27. Standing Wide Legged Pose Hands 28. Horse Pose Side Stretch Hand On Bend Tandavasana On Hips Prasarita Tadasana Hands On Floor Vatayanasana Side Stretch Hand On Hips Floor 29. Standing Pigeon Pose Tada 30. Half Bound Lotus Tree Pose Strap 31. -

Effects of an 8-Week Yoga-Based Physical Exercise Intervention on Teachers’ Burnout

sustainability Article Effects of an 8-Week Yoga-Based Physical Exercise Intervention on Teachers’ Burnout Francesca Latino , Stefania Cataldi * and Francesco Fischetti Department of Basic Medical Sciences, Neuroscience, and Sense Organs, University of Bari “Aldo Moro”, 70123 Bari, Italy; [email protected] (F.L.); francesco.fi[email protected] (F.F.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.:+39-34-9125-8004 Abstract: The purpose of this quasi-experimental study was to investigate the efficacy of an 8-week yoga-based physical exercise program to improve mental and emotional well-being and consequently reduce burnout among teachers. We considered yoga because it is a discipline that enhances body awareness and encourages the contact with nature and the respect for every form of life, with a view to a more sustainable and greener global system. We recruited 40 professional educators (40–47 years), teachers in a public high school who reported perceiving signs of stress and emotional discomfort. We randomly assigned the 40 professional educators to either an experimental yoga practice (~60 min, twice a week) group (n = 20) or a control group (n = 20) that received a nonspecific training program (~60 min, twice a week). At baseline and after training we administered the Maslach Burnout Inventory: Educators Survey (MBI-ES) and the State Mindfulness Scale (SMS) to assess teachers’ perceived level of awareness and professional burnout. We found a significant Time × Group interaction for the MBI-ES and SMS, reflecting a meaningful experimental group improvement (p < 0.001). No significant pre–post changes were found in the control group. The results suggest that an 8-week yoga practice could aid teachers to achieve a greater body and emotional awareness and Citation: Latino, F.; Cataldi, S.; prevent professional burnout.