LD5655.V856 1982.W444.Pdf (11.60Mb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tippecanoe County - Warrant Recall Data As of June 1, 2015

TIPPECANOE COUNTY - WARRANT RECALL DATA AS OF JUNE 1, 2015 Name Last Known Address at Time of Warrant Issuance ABBOTT, RANDY CARL STRAWSTOWN AVE NOBLESVILLE IN ABDUL-JABAR, HAKIMI SHEETZ STREET WEST LAFAYETTE IN ABERT, JOSEPH DEAN W 5TH ST HARDY AR ABITIA, ANGEL S DELAWARE INDIANAPOLIS IN ABRAHA, THOMAS SUNFLOWER COURT INDIANAPOLIS IN ABRAMS, SCOTT JOSEPH ABRIL, NATHEN IGNACIO S 30TH ST LAFAYETTE IN ABTIL, CHARLES HALSEY DRIVE WEST LAFAYETTE IN ABUASABEH, FAISAL B NEIL ARMSTRONG DR WEST LAFAYETTE IN ABUNDIS, JOSE DOMINGO LEE AVE COOKVILLE TN ACEBEDO, RICARDO S 17TH ST LAFAYETTE IN ACEVEDO, ERIC JAVIER OAK COURT LAFAYETTE IN ACHOR, ROBERT GENE II E COLUMBIA ST LOGANSPORT IN ACOFF, DAMON LAMARR LINDHAM CT MECHANICSBURG PA ACOSTA, ANTONIO E MAIN STREET HOOPESTON IL ACOSTA, MARGARITA ROSSVILLE IN ACOSTA, PORFIRIO DOMINGUIEZ N EARL AVE LAFAYETTE IN ADAMS JR, JOHNNY ALLAN RICHMOND CT LEBANON IN ADAMS, KENNETH A W 650 S ROSSVILLE IN ADAMS, MATTHEW R BROWN STREET LAFAYETTE IN ADAMS, PARKE SAMUEL N 26TH ST LAFAYETTE IN ADAMS, RODNEY S 8TH ST LAFAYETTE IN ADAMSON, JOSHUA PAUL BUNTING LN LAFAYETTE IN ADAMSON, RONALD LEE SUNSET RIDGE DR LAFAYETTE IN ADCOX, SCOTT M LAWN AVE WEST LAFAYETTE IN ADINA-ZADE, ABDOUSSALAM NORTH 6TH STREET LAFAYETTE IN ADITYA, SHAH W WOOD ST WEST LAFAYETTE IN ADKINS, DANIEL L HC 81 BOX 6 BALLARD WV ADKINS, JARROD LEE S 28TH ST LAFAYETTE IN ADRIANSON, MARK ANDREW BOSCUM WINGATE IN AGEE, PIERE LAMAR DANUBE INDIANAPOLIS IN AGUAS, ANTONIO N 10TH ST LAFAYETTE IN AGUILA-LOPEZ, ISAIAS S 16TH ST LAFAYETTE IN AGUILAR, FRANSICO AGUILAR, -

The Lawrence Stanley Lee (LSL) Marylebone Madonna Window

The Lawrence Stanley Lee (LSL) Marylebone Madonna Window Installed in 1955 as part of post war damage work to the parish church. The window is the first window on the liturgical south (geographically west) side of the ground floor of the nave. The Arms of those of the old Borough of St Marylebone. The motto reads ‘Let it be according to your Word’ part of the Magnificat or Song of Mary in Luke 1.46-55 Lawrence Stanley Lee (18 September 1909 – 25 April 2011) was a British stained glass artist whose work spanned the latter half of the 20th century. He was best known for leading the project to create ten huge windows for the nave of the new Coventry Cathedral. His other work includes windows at Guildford and Southwark Cathedrals as well as a great number of works elsewhere in the UK, and some in Canada, Australia and New Zealand. Early Life Lee was born in Chelsea Hospital for Women on 18 September 1909. His family moved to Weybridge where his father, William, a chauffeur and engineer, had a garage near to the Booklands’ Race Track. Lawrence's mother, Rose, was deeply religious and it was this influence that gave him the appreciation of biblical symbolism that became an important feature of his work. His parents divorced and Lawrence moved with his mother to New Malden. At the local Methodist church he met Dorothy Tucker, later to become his wife. He left school at 14, but won a scholarship to Kingston School of Art. A further award in 1927 enabled him to attend the Royal College of Art, where he studied stained glass under Martin Travers, graduating in 1930. -

Rose Window Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia Rose Window from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

6/19/2016 Rose window Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Rose window From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia A rose window or Catherine window is often used as a generic term applied to a circular window, but is especially used for those found in churches of the Gothic architectural style and being divided into segments by stone mullions and tracery. The name “rose window” was not used before the 17th century and according to the Oxford English Dictionary, among other authorities, comes from the English flower name rose.[1] The term “wheel window” is often applied to a window divided by simple spokes radiating from a central boss or opening, while the term “rose window” is reserved for those windows, sometimes of a highly complex design, which can be seen to bear similarity to a multipetalled rose. Rose windows are also called Catherine windows after Saint Catherine of Alexandria who was sentenced to be executed on a spiked wheel. A circular Exterior of the rose at Strasbourg window without tracery such as are found in many Italian churches, is Cathedral, France. referred to as an ocular window or oculus. Rose windows are particularly characteristic of Gothic architecture and may be seen in all the major Gothic Cathedrals of Northern France. Their origins are much earlier and rose windows may be seen in various forms throughout the Medieval period. Their popularity was revived, with other medieval features, during the Gothic revival of the 19th century so that they are seen in Christian churches all over the world. Contents 1 History 1.1 Origin 1.2 The windows of Oviedo Interior of the rose at Strasbourg 1.3 Romanesque circular windows Cathedral. -

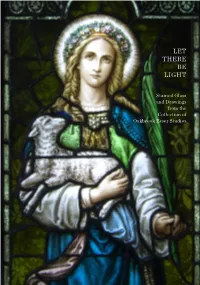

Let There Be Light

LET THERE BE LIGHT Stained Glass and Drawings from the Collection of Oakbrook Esser Studios 1 The exhibition Let there be Light Stained glass and Drawings from the Collection of Oakbrook esser Studios and related programs have been made possible through funding by the Marquette University Andrew W. Mellon Fund, the Kathleen and Frank Thometz Charitable Foundation, the Eleanor H. Boheim Endowment Fund and the John P. Raynor, S.J. Endowment Fund. This exhibition came to fruition through the dedication and work of many people. First and foremost, we would like to extend our sincere thanks to Paul Phelps, owner of Oakbrook Esser Studios in Oconomowoc, Wisconsin. Paul treated us with great kindness and generously gave his time and knowledge throughout the two year process of putting this exhibition together. The incredibly talented staff of Oakbrook Esser welcomed us to the studio time and again and graciously worked around our many intrusions. Warm thanks in particular go to Dondi Griffin and Johann Minten. Davida Fernandez-Barkan, Haggerty intern and art history major at Harvard University, was integral in laying the groundwork for the exhibition. Her thorough research paved the way for the show to come to life. We also want to thank essayists Dr. Deirdre Dempsey (associate professor, Marquette University, Department of Theology) and James Walker (glass artist, New Zealand) for their contributions Cover image to this catalogue. Unknown Artist and Studio St. Agnus, (detail), c. 1900 Antique glass, flashed glass, pigment, enamels, silver staining 57 x 22” checklist #7 LET THERE BE LIGHT Stained Glass and Drawings from the Collection of Oakbrook Esser Studios Attributed to Tiffany Studios New York, New York Setting fabricated by Oakbrook Esser Studios Oconomowoc, Wisconsin Head of Christ, c. -

The New Romantics: Romantic Themes in the Poetry of Guo Moruo and Xu Zhimo

W&M ScholarWorks Undergraduate Honors Theses Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 5-2009 The New Romantics: Romantic Themes in the Poetry of Guo Moruo and Xu Zhimo Shannon Elizabeth Reed College of William and Mary Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses Part of the Chinese Studies Commons, and the Literature in English, British Isles Commons Recommended Citation Reed, Shannon Elizabeth, "The New Romantics: Romantic Themes in the Poetry of Guo Moruo and Xu Zhimo" (2009). Undergraduate Honors Theses. Paper 305. https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses/305 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Table of Contents Introduction: Romanticism ..............................................................1 Part I: Historical Context ..............................................................10 Part II: Guo Moruo ......................................................................26 Part III: Xu Zhimo .......................................................................58 Conclusion ..................................................................................87 Appendix: Full Text of Selected Poems ..........................................89 Guo Moruo’s Poems ................................................................................................................ -

A Study of Residential Stained Glass: the Work of Nicola D'ascenzo Studios from 1896 to 1954

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Theses (Historic Preservation) Graduate Program in Historic Preservation 1990 A Study of Residential Stained Glass: The Work of Nicola D'Ascenzo Studios from 1896 to 1954 Lisa Weilbacker University of Pennsylvania Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses Part of the Historic Preservation and Conservation Commons Weilbacker, Lisa, "A Study of Residential Stained Glass: The Work of Nicola D'Ascenzo Studios from 1896 to 1954" (1990). Theses (Historic Preservation). 252. https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses/252 Copyright note: Penn School of Design permits distribution and display of this student work by University of Pennsylvania Libraries. Suggested Citation: Weilbacker, Lisa (1990). A Study of Residential Stained Glass: The Work of Nicola D'Ascenzo Studios from 1896 to 1954. (Masters Thesis). University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA. This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses/252 For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Study of Residential Stained Glass: The Work of Nicola D'Ascenzo Studios from 1896 to 1954 Disciplines Historic Preservation and Conservation Comments Copyright note: Penn School of Design permits distribution and display of this student work by University of Pennsylvania Libraries. Suggested Citation: Weilbacker, Lisa (1990). A Study of Residential Stained Glass: The Work of Nicola D'Ascenzo Studios from 1896 to 1954. (Masters Thesis). University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, -

Let There Be Light Catalogue

LET THERE BE LIGHT Stained Glass and Drawings from the Collection of Oakbrook Esser Studios 1 LET THERE BE LIGHT Stained Glass and Drawings from the Collection of The exhibition Let There be Light Stained Glass and Drawings Oakbrook Esser Studios from the Collection of Oakbrook Esser Studios and related programs have been made possible through funding by the Marquette University Andrew W. Mellon Fund, the Kathleen and Frank Thometz Charitable Foundation, the Eleanor H. Boheim Endowment Fund and the John P. Raynor, S.J. Endowment Fund. This exhibition came to fruition through the dedication and work of many people. First and foremost, we would like to extend our sincere thanks to Paul Phelps, owner of Oakbrook Esser Studios in Oconomowoc, Wisconsin. Paul treated us with great kindness and generously gave his time and knowledge throughout the two year process of putting this exhibition together. The incredibly talented staff of Oakbrook Esser welcomed us to the studio time and again and graciously worked around our many intrusions. Warm thanks in particular go to Dondi Griffin and Johann Minten. Davida Fernandez-Barkan, Haggerty intern and art history major at Harvard University, was integral in laying the groundwork for the exhibition. Her thorough research paved the way for the show to come to life. We also want to thank essayists Dr. Deirdre Dempsey (associate professor, Marquette University, Department of Theology) and James Walker (glass artist, New Zealand) for their contributions Cover image to this catalogue. Unknown Artist and Studio St. Agnus, (detail), c. 1900 Antique glass, flashed glass, pigment, enamels, silver staining 57 x 22” checklist #7 Attributed to Tiffany Studios New York, New York Ross Taylor (1916-2001) Setting fabricated by Oakbrook Esser Studios Enterprise Art Glass Works Oconomowoc, Wisconsin Milwaukee, Wisconsin Head of Christ, c. -

Stained and Painted Glass Janette Ray Booksellers, York, England

Stained and Painted Glass Janette Ray Booksellers, York, England Janette Ray Booksellers, 8 Bootham, York YO30 7BL UK. Tel: +44 (0)1904 623088 email [email protected] STAINED AND PAINTED GLASS: CATALOGUE 16 Introduction: This catalogue is our first specialist list on aspects of stained and painted glass. It includes material on making glass, commentaries on glass in situ, including a selection of out of print volumes from Corpus Vitrearum, monographs on individual makers and a small group of items which comprise original designs for glass. It is designed to appeal to those who have a general interest in the subject alongside those with specific interests in periods or individual artists. We would particularly draw your attention to Christopher Whall’s rare promotional booklet for his own firm which has original photographs of items he made,(no 31 ) and other trade catalogues, the massive colour illustrated portfolio Vorbildliche Glasmalereien aus dem späten Mittelalter und der Renaissancezeit which records glass in pre First World War Germany (no 99), the original heraldic designs recorded by F C Eden at Aveley Belhus. (no 187) and the substantial collection of original material from Hardman’s in Birmingham when the company was under the jurisdiction of Patrick Feeney and Donald Taunton. (no 188 ) [Cover design from the collection S268] We have not included Journals in the list but have a large stock of the major academic publication of the Society of Glass Painters and other journals and welcome any enquiries on this subject. Furthermore, there are many small pamphlets which provide valuable insights into the windows in churches all over Great Britain and beyond. -

The Wind and Beyond of History at Auburn University, Has Written About Aerospace History for the Past 25 Years

About the editors: James R. Hansen, Professor The Wind and Beyond of History at Auburn University, has written about aerospace history for the past 25 years. His newest A Documentary Journey into the History book, First Man: The Life of Neil A. Armstrong (Simon & TheWind and The and of Aerodynamics in America Schuster, 2005), provides the authorized and definitive Beyond Wind biography of the famous test pilot, astronaut, and first Volume II: Reinventing the Airplane man on the Moon. His two-volume study of NASA The airplane ranks as one of history’s most inge- Langley Research Center—Engineer in Charge (NASA SP- Beyond nious and phenomenal inventions. It has surely been 4305, 1987) and Spaceflight Revolution (NASA SP-4308, A Documentary Journey A Documentary Journey into the one of the most world changing. How ideas about 1995) earned significant critical acclaim. His other into the History of aerodynamics first came together and how the science books include From the Ground Up (Smithsonian, 1988), History of Aerodynamics in America and technology evolved to forge the airplane into the Enchanted Rendezvous (NASA Monographs in Aerospace Aerodynamics revolutionary machine that it became is the epic story History #4, 1995), and The Bird Is On The Wing (Texas in America told in this six-volume series, The Wind and Beyond: A A&M University Press, 2003). Documentary Journey through the History of Aerodynamics in Jeremy R. Kinney is a curator in the Aeronautics America. Division, National Air and Space Museum, Smithsonian Institution and holds a Ph.D. in the history of technology Following up on Volume I’s account of the invention from Auburn. -

STAINED GLASS in SCOTLAND: a PERSPECTIVE Lain B

The Church Service Society Record STAINED GLASS IN SCOTLAND: A PERSPECTIVE lain B. Galbraith This introductory sketch to a large subject endeavours to outline some of the trends, styles and influences at work in stained glass in Scotland from its revival around 1820 to the present time. In the massive chronological survey of stained glass published in 1976, Lawrence Lee describes glass as an enigmatic natural substance formed by melting certain materials and cooling them in a certain way1 The use of the adjective `enigmatic' is both interesting and apposite and serves as an introduction to this article. There is sometimes present in stained glass, because of its relationship with light, an elusive, inexplicable element that defies description — a mysterious factor that is indeed enigmatic. This is not totally surprising considering the different strands that combine to form stained glass — colour, form, symbolism, craftsmanship; all contained within a living relationship with light. And it is light that gives life to stained glass. Light and life and mystery. Glass has an ancient history, as Pliny's account in Historia Naturalis illustrates. There is evidence that coloured glass existed in Egypt, and in the Mediterranean world.' Within the Roman Empire, glass makers practised and developed their art and the glazing of window spaces became a custom. Thus, when the Christian Church became established upon a European scale, the basis for the making of stained glass was already established. Stained glass, however, is principally a Christian art form, and, as such, its origins go back to the sixth century, when Saint Gregory had the windows of Saint Martin of Tours glazed with coloured glass. -

Annual Report, 1931

t PENNSYLVANIA MUSEUM OF ART nFTY-FIFTH ANNUAL REPORT PHILADELPHIA 1931 Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2011 with funding from LYRASIS Members and Sloan Foundation http://www.archive.org/details/annualreport193100penn FIFTY-FIFTH ANNUAL REPORT OF THE PENNSYLVANIA MUSEUM OF ART FOR THE YEAR ENDED MAY 31, 1931 WITH THE LIST OF MEMBERS PHILADELPHIA 1931 8 «&&**on*-* OFFICERS FOR 1931-1932 PRESIDENT ELI KIRK PRICE VICE-PRESIDENTS WILLIAM M. ELKINS J. STOGDELL STOKES SECRETARY JULIUS ZIEGET TREASURER GIRARD TRUST COMPANY BOARD OF TRUSTEES EX OFFICIIS Gifford Pinchot, Governor of Pennsylvania Harry A. Mackey, Mayor of Philadelphia Edwin R. Cox, President of Philadelphia City Council Edward T. Stotesbury, President of Commissioners of Fairmount Park ELECTED BY THE MEMBERS John F. Braun Mrs. Arthur V. Meigs Mrs. Edward Browning Mrs. Frank Thorne Patterson William M. Elkins Eli Kirk Price John Gribbel Edward B. Robinette John S. Jenks Thomas Robins Emory McMichael J. Stogdell Stokes George D. Widener WE UNIVERSITY OF THE* LIBRARY- AD^u, /rn STANDING COMMITTEES* COMMITTEE ON MUSEUM JOHN S. JENKS, Chairman MORRIS R. BOCKIUS MRS. FRANK THORNE PATTERSON MRS. HAMPTON L. CARSON ELI KIRK PRICE MRS. HENRY BRINTON COXE EDWARD B. ROBINETTE WILLIAM M. ELKINS LESSING J. ROSENWALD MRS. CHARLES W. HENRY J. STOGDELL STOKES GEORGE H. LORIMER MRS. EDWARD T. STOTESBURY MRS. JOHN D. McILHENNY ROLAND L. TAYLOR GEORGE D. WIDENER COMMITTEE ON INSTRUCTION ELI KIRK PRICE, Chairman CHARLES L. BORIE, JR. ALLEN R. MITCHELL, JR. MILLARD D. BROWN MRS. H. S. PRENTISS NICHOLS MRS. HENRY BRINTON COXE MRS. FRANK THORNE PATTERSON JOHN S. JENKS MRS. LOGAN RHOADS MRS. -

2017 Around Southwark Cathedral

Reviews: Walk & Talk ‘Stained glass artists of Southwark Cathedral’ with Caroline Swash Next was St Mary-Le-Bow, another church rebuilt by Wren after the Great Fire, then devastated during the Blitz. Post WW2, the rebuilding programme was entrusted to an Anglo-Catholic architect Laurence King, who, during his association with the firm Faithcraft, manufacturers of church furniture, met the 30-year-old John Hayward, to whom he then entrusted designing the entire interior of the chancel including the stained glass. In striking contrast to the previous church, the interior seems sombre, and Hayward’s windows glow with jewel-like intensity. The West window, predominantly a blazing red, celebrates the government of the city, its important historic buildings and institutions with their ‘pomp and ceremony’, including a aroline Swash, in her tireless promotion of stained glass, decorative interpretation of the insignia of the twelve principal Cplanned a day of celebration of this extraordinary medium, Livery Companies. In contrast, the East windows have the archaic on 20th July, starting at her home, with her personal collection character of a Byzantine mosaic, both in their imagery and in of works in glass and other media, and from thence walking to Hayward’s technique: small view three nearby city churches. Then crossing the Thames to fragments of colour, like Southwark Cathedral to hear Benjamin Finn speak about his tesserae, piercing the dense beautiful windows for the Millenium Library, and finally a mesh of lead lines. The central scholarly and illuminating talk by Caroline herself, on the varied panel shows Christ in Glory and fascinating stained glass in Southwark Cathedral.