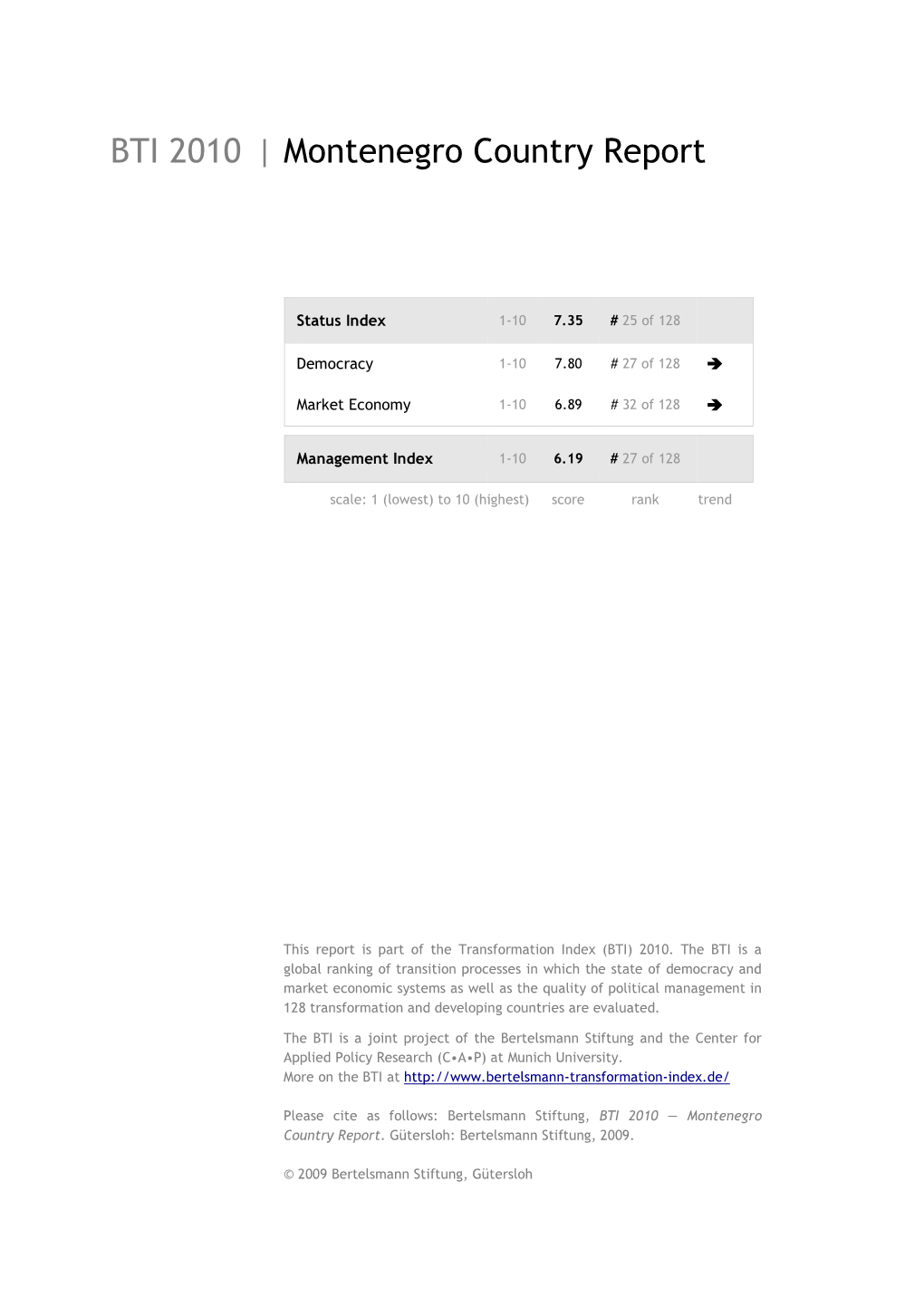

Montenegro Country Report BTI 2010

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Propaganda Made-To-Measure: Dimensions of Risk and Resilience in the Western Balkans

ASYMMETRIC THREATS PROGRAMME A Study of Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Kosovo, Montenegro, North Macedonia and Serbia PROPAGANDA MADE-TO-MEASURE: DIMENSIONS OF RISK AND RESILIENCE IN THE WESTERN BALKANS Rufin Zamfir (editor) Funded by: A project by I Bucharest, Romania May, 2019 The report can be accessed at www.global-focus.eu or ordered at [email protected] +40-721259205 26, Hristo Botev bvd, et. 4, ap. 9 Bucharest, Sector 3 GlobalFocus Center is an independent international studies think-tank which produces in-depth research and high quality analysis on foreign policy, security, European affairs, good governance and development. It functions as a platform for cooperation and dialogue among individual experts, NGOs, think-tanks and public institutions from Romania and foreign partners. The Asymmetric Threats programme focuses on strategic communications, terrorism and radicalization, cyber security and hybrid war. DISCLAIMER The views expressed belong to the individual authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the GlobalFocus Center. GlobalFocus Center reserves all rights for the present publication. Parts thereof can only be reproduced or quoted with full attribution to the GlobalFocus Center and mention of publication title and authors' names. Full reproduction is only permitted upon obtaining prior written approval from the GlobalFocus Center. OiiOpinions expressed in thispublica tion donot necessarilyrepresent those of the BlkBalkan Trust for Democracy, the German Marshall Fund of the United States, or its partners. Argument and Methodological Explanation (by Rufin Zamfir) pg. 1 Albania (by Agon Maliqi) pg. 7 Society pg. 9 Economy pg. 16 Politics pg. 21 Foreign Policy and Security pg. 26 Bosnia and Herzegovina (by Dimitar Bechev) pg. -

Vulnerabilities to Russian Influence in Montenegro

KREMLIN WATCH REPORT VULNERABILITIES TO RUSSIAN INFLUENCE IN MONTENEGRO Kremlin Watch Program 2019 EUROPEAN VALUES CENTER FOR SECURITY POLICY European Values Center for Security Policy is a non-governmental, non-partisan institute defending freedom and sovereignty. We protect liberal democracy, the rule of law, and the transatlantic alliance of the Czech Republic. We help defend Europe especially from the malign influences of Russia, China, and Islamic extrem- ists. We envision a free, safe, and prosperous Czechia within a vibrant Central Europe that is an integral part of the transatlantic community and is based on a firm alliance with the USA. Our work is based on individual donors. Use the form at: http://www.europeanvalues.net/o-nas/support- us/, or send your donation directly to our transparent account: CZ69 2010 0000 0022 0125 8162. www.europeanvalues.net [email protected] www.facebook.com/Evropskehodnoty KREMLIN WATCH PROGRAM Kremlin Watch is a strategic program of the European Values Center for Security Policy which aims to ex- pose and confront instruments of Russian influence and disinformation operations focused against West- ern democracies. Author Mgr. Liz Anderson, student of Security and Strategic Studies at Masaryk University and Kremlin Watch Intern Editor Veronika Víchová, Head of Kremlin Watch Program, European Values Center for Security Policy Image Copyright: Page 1, 4, 12: NATO 2 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY With a population of a little more than 650,000 citizens, levels of Montenegrin society, but most prominently in Montenegro is NATO’s newest and smallest member. It the economic, political, civil society, media, and religious joined the Alliance controversially and without a realms. -

Russia's Role in the Balkans – Cause for Concern?

Russia’s Role in the Balkans – Cause for Concern? By David Clark and Dr Andrew Foxall June 2014 Published in June 2014 by The Henry Jackson Society The Henry Jackson Society 8th Floor, Parker Tower 43-49 Parker Street London WC2B 5PS Registered charity no. 1140489 Tel: +44 (0)20 7340 4520 www.henryjacksonsociety.org © The Henry Jackson Society 2014 The Henry Jackson Society All rights reserved The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and are not necessarily indicative of those of The Henry Jackson Society or its Trustees Russia’s Role in the Balkans – Cause for Concern? By David Clark and Dr Andrew Foxall All rights reserved Front Cover Image: Welding first joint of Serbian section of South Stream gas pipeline © www.gazprom.com Russia’s Role in the Balkans – Cause for Concern? AUTHOR | AUTHOR By David Clark and Dr Andrew Foxall June 2014 Russia’s Role in the Balkans – Cause for Concern? About the Authors David Clark is Chair of the Russia Foundation and served as Special Adviser at the Foreign Office 1997-2001. Dr Andrew Foxall is Director of the Russia Studies Centre at The Henry Jackson Society. He holds a DPhil from the University of Oxford. i Russia’s Role in the Balkans – Cause for Concern? The Henry Jackson Society The Henry Jackson Society is a cross-partisan think-tank based in London. The Henry Jackson Society is a think tank and policy-shaping force that fights for the principles and alliances which keep societies free – working across borders and party lines to combat extremism, advance democracy and real human rights, and make a stand in an increasingly uncertain world. -

Change, Continuity and Political Crisis. Montenegro's Political Trajectory

Change, Continuity and Political Crisis. Montenegro’s Political Trajectory (1988-2016) Kenneth Morrison Abstract. Montenegro has passed through more than two decades of flux to reach its current status as a NATO member and European Union (EU) candidate. The smallest republic of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, Montenegro’s modern history has been characterised by both significant change (in statehood) and relative continuity (in leadership). The author focuses on the period between the republic’s first multi-party elections in 1990, through the 1997 split within the ruling Democratic Party of Socialists (DPS) and the May 2006 independence referendum to the parliamentary elections of 2016 and the country’s ongoing political crisis, assessing the most significant political developments throughout the aforementioned period. Kenneth Morrison is Professor of Modern Southeast Europan History and Co-Director of the Jean Monnet Centre for European Governance at De Monfort University in Leicester. In May 2016, Montenegro celebrated the ten-year anniversary of the re-establishment of its independence, and it had been a decade in which its government faced myriad challenges. The referendum itself was a pivotal moment in Montenegro’s modern history and its trajectory since has been shaped by it. Held on 21 May 2006, the referendum sought to determine whether the republic would remain a partner within the state union of Serbia & Montenegro, created as a consequence of the March 2002 ‘Belgrade Agreement’, or become an independent state. A narrow majority of 55.5 % (the threshold was set at 55 per cent) of the republic’s citizens opted for the latter, heralding Montenegro’s re-emergence as an internationally recognised independent state. -

The Impact of Geography and Ethnicity on EU Enlargement:New

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University Political Science Dissertations Department of Political Science Spring 5-10-2017 The mpI act of Geography and Ethnicity on EU Enlargement:New Evidence from the Accession of Eastern Europe Diana Petrova White Georgia State University Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.gsu.edu/political_science_diss Recommended Citation White, Diana Petrova, "The mpI act of Geography and Ethnicity on EU Enlargement:New Evidence from the Accession of Eastern Europe." Dissertation, Georgia State University, 2017. http://scholarworks.gsu.edu/political_science_diss/43 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Political Science at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Political Science Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE IMPACT OF GEOGRAPHY AND ETHNICITY ON EU ENLARGEMENT NEW EVIDENCE FROM THE ACCESSION OF EASTERN EUROPE by DIANA WHITE Under the Direction of Jelena Subotic, PhD ABSTRACT In this dissertation I argue that established EU member states slow down accession of Eastern European members because they do not consider them suitable for a western-style liberal democracy due to the pronounced presence of specific factors related to ethnicity and geography in the region. I evaluate EU enlargement on wave-by-wave basis and conclude that the major concern with accessing Eastern Europe -

DI Montnegro Legislative Strengthening and Political Party

MONTENEGRO LEGISLATIVE STRENGTHENING AND POLITICAL PARTY PROGRAM PERFORMANCE EVALUATION FINAL REPORT Prepared under the Democracy and Governance Analytical Services Indefinite Quantity Contract, #DFD-I-00-04-00229-00 Submitted to: USAID/Montenegro NOVEMBER 2011 This publication was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development. It was prepared by Democracy International, Inc. Prepared by: Under Contract Number AID-OAA-I-10-00004, Democracy and Governance Analytical Services Indefinite Quantity Contract Submitted to: USAID/Montenegro Prepared by: Lincoln Mitchell, PhD Gregory Minjack Milos Uljarevic Contractor: Democracy International, Inc. 4802 Montgomery Lane Bethesda, MD 20814 Tel: 301-961-1660 www.democracyinternational.com LEGISLATIVE STRENGTHENING AND POLITICAL PARTY PROGRAM PERFORMANCE EVALUATION FINAL REPORT NOVEMBER 2011 DISCLAIMER The authors’ views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the Unit- ed States Agency for International Development or the United States Government. This evalua- tion was made possible by the support of the American people through the United States Agen- cy for International Development (USAID). CONTENTS CONTENTS ............................................................................................................................... 1 ACCRONYMS ........................................................................................................................... 2 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ...................................................................................................... -

The Determinants of Ethnic Minority Party Formation and Success in Europe

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Illinois Digital Environment for Access to Learning and Scholarship Repository THE DETERMINANTS OF ETHNIC MINORITY PARTY FORMATION AND SUCCESS IN EUROPE BY DANAIL L. KOEV DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2014 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Carol Leff, Chair Professor Robert Pahre Professor William Bernhard Associate Professor Milan Svolik ii Abstract Why do some ethnic minority groups in Europe form political parties of their own in order to obtain political representation, whereas others choose to work within the confines of established, mainstream political parties? Further, why do some ethnic minority parties (EMPs) achieve electoral success, whereas others fail? In addressing these questions, I incorporate insights from history and social psychology to develop an original theory of EMP emergence and success. I argue that an ethnic minority group’s historical background influences its political engagement strategies through sociopsychological processes. I propose that native groups (those that inhabited the territory of the modern-day state in which they reside prior to that state’s establishment) and groups with historical experiences of autonomous self-rule are more likely to form ethnic minority parties, and that EMPs formed by such groups are more likely to enjoy electoral success. I argue that groups possessing one or both of these characteristics are more likely to exhibit the traits of positive distinctiveness and shared grievances, contributing to the development of a salient collective political identity. -

Major Political Parties Coverage for Data Collection 2021 Country Major

Major political parties Coverage for data collection 2021 Country Major political parties EU Member States Christian Democratic and Flemish (Chrétiens-démocrates et flamands/Christen-Democratisch Belgium en Vlaams/Christlich-Demokratisch und Flämisch) Socialist Party (Parti Socialiste/Socialistische Partij/Sozialistische Partei) Forward (Vooruit) Open Flemish Liberals and Democrats (Open Vlaamse Liberalen en Democraten) Reformist Movement (Mouvement Réformateur) New Flemish Alliance (Nieuw-Vlaamse Alliantie) Ecolo Flemish Interest (Vlaams Belang) Workers' Party of Belgium (Partij van de Arbeid van België) Green Party (Groen) Bulgaria Citizens for European Development of Bulgaria (Grazhdani za evropeysko razvitie na Balgariya) Bulgarian Socialist Party (Bulgarska sotsialisticheska partiya) Movement for Rights and Freedoms (Dvizhenie za prava i svobodi) There is such people (Ima takav narod) Yes Bulgaria ! (Da Bulgaria!) Czech Republic Mayors and Independents STAN (Starostové a nezávislí) Czech Social Democratic Party (Ceská strana sociálne demokratická) ANO 2011 Okamura, SPD) Denmark Liberal Party (Venstre) Social Democrats (Socialdemokraterne/Socialdemokratiet) Danish People's Party (Dansk Folkeparti) Unity List-Red Green Alliance (Enhedslisten) Danish Social Liberal Party (Radikale Venstre) Socialist People's Party (Socialistisk Folkeparti) Conservative People's Party (Det Konservative Folkeparti) Germany Christian-Democratic Union of Germany (Christlich Demokratische Union Deutschlands) Christian Social Union in Bavaria (Christlich-Soziale -

The 2016 Coup Attempt in Montenegro: Is Russia's Balkans Footprint Expanding?

RUSSIA FOREIGN POLICY PAPERS THE 2016 COUP ATTEMPT IN MONTENEGRO: Is Russia’s Balkans Footprint Expanding? DIMITAR BECHEV FOREIGN POLICY RESEARCH INSTITUTE All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. © 2018 by the Foreign Policy Research Institute COVER: Old Montenegro flag in brick wall, Adobe Stock. April 2018 RUSSIA FOREIGN POLICY PAPERS THE 2016 COUP ATTEMPT IN MONTENEGRO: Is Russia’s Balkans Footprint Expanding? By: Dimitar Bechev Dimitar Bechev is a research fellow at the Center for Slavic, Eurasian, and East European Studies at the University of North Carolina Chapel Hill and a a nonresident fellow at the Atlantic Council. His new book, Rival Power: Russia in Southeast Europe, is published by Yale University Press. Executive Summary On October 15, 2016, the day before Montenegro’s hotly contested legislative elections, Podgorica authorities thwarted an alleged coup attempt. Asserting that the conspirators aimed to prevent Montenegro’s imminent NATO accession, they blamed Moscow as the main instigator. Reflecting on the long-standing historical ties between Russia and Montenegro—and particularly their strong economic relations throughout the 2000s—Moscow’s newfound antagonism appears incongruous. Yet, this case reflects a critical shift in Moscow’s power projection in the Balkans. The decline in commodity prices in the early 2010s crippled Moscow’s economic influence in Montenegro. Shortly after, the annexation of Crimea led to a standoff with the West, in which Montenegrin authorities sided with their soon-to-be European allies. -

The Role of Elites in the Formation of National Identities: the Ac Se of Montenegro Muhammed F

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School November 2017 The Role of Elites in the Formation of National Identities: The aC se of Montenegro Muhammed F. Erdem University of South Florida, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the Political Science Commons Scholar Commons Citation Erdem, Muhammed F., "The Role of Elites in the Formation of National Identities: The asC e of Montenegro" (2017). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/7020 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Role of Elites in the Formation of National Identities: The Case of Montenegro by Muhammed F. Erdem A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts School of Interdisciplinary Global Studies College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Co-Major Professor: Darrell Slider, Ph.D. Co-Major Professor: Bernd Reiter, Ph.D. Giovanna Benadusi, Ph.D. Date of Approval: October 31, 2017 Keywords: Montenegro, Nationalism, Ethnicity, National identity, Elite competition Copyright © 2017, Muhammed F. Erdem i TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract ......................................................................................................................................... -

This Thesis Was Completed at the University of Bamberg in the Framework of the Double Masters Program of the University of Bamberg and the University of Macedonia

This thesis was completed at the University of Bamberg in the framework of the Double Masters Program of the University of Bamberg and the University of Macedonia. It was recognized by the MA in Politics and Economics of Contemporary Eastern and Southeastern Europe of the Department of Balkan, Slavic and Oriental Studies of the University of Macedonia. The Effectiveness of the EU’s Conditionality Policy in the Western Balkans Master Thesis in Political Science at the Department of Social and Economic Sciences of the Otto-Friedrich-University in Bamberg Chair: International Relations Head of Chair: Professor Dr. Thomas Ghering Adviser: Professor Dr. Thomas Ghering Author: Sofia Chatzistefanou Matriculation Number: 1971660 Address: Pythagora 14A, Panorama Thessaloniki Greece 55236 E-Mail: [email protected] Field of Study: Political Science, Master’s Degree 5 term of studying in this field/ 5 term at university Date of Submission: [05/09/2019] Page | 2 Abstract Despite having many common characteristics such as their Yugoslav history, their transitioning economies, the presence of many ethnic minorities in their territories and their geographical area, the Western Balkans comply at very different rates with the EU’s recommendation with one another. Thus, to examine the effectiveness of the EU’s conditionality policy, additional factors must be found. The focus here is on domestic factors and more specifically party competition and policy salience. To examine the above, a Rational Institutionalist Approach of the determinants of the effectiveness of the EU’s Conditionality is used, that views conditionality as “Reinforcement by Reward”. The method used to analyse the question and the stated hypothesis is a comparative case study between the energy and the environmental sectors of Bosnia & Herzegovina and Montenegro. -

EU Integration and Party Politics in the Balkans

EU integration and party politics in the Balkans EPC ISSUE PAPER NO. 77 SEPTEMBER 2 0 1 4 Edited by Corina Stratulat EUROPEAN POLITICS AND INSTITUTIONS ISSN 1782-494X PROGRAMME The EPC’s Programme on European Politics and Institutions With the entry into force of the Lisbon Treaty, the new focus of this programme is on adapting the EU’s institutional architecture to take account of the changed set-up and on bringing the EU closer to its citizens. Continuing discussion on governance and policymaking in Brussels is essential to ensure that the European project can move forward and respond to the challenges facing the Union in the 21st century in a democratic and effective manner. This debate is closely linked to the key questions of how to involve European citizens in the discussions over its future; how to win their support for European integration and what are the prospects for, and consequences of, further enlargement towards the Balkans and Turkey. This programme focuses on these core themes and brings together all the strands of the debate on a number of key issues, addressing them through various fora, task forces and projects. It also works with other programmes on cross-cutting issues such as the reform of European economic governance or the new EU foreign policy structures. ii Table of Contents About the authors .................................................................................................................................... v List of tables .........................................................................................................................................