A New Algorithm in Patients with Elevated And/Or Rising Prostate-Specific Antigen Level, Minor Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2005 Tumori Della Vescica Visualizza

Basi scientifiche per la definizione di linee-guida in ambito clinico per i Tumori della Vescica Luglio 2005 1 2 PREFAZIONE Le “Basi scientifiche per la definizione di linee guida in ambito clinico per i Tumori della Vescica” rappresentano un ulteriore risultato del progetto editoriale sponsorizzato e finanziato dai Progetti Strategici Oncologia del CNR-MIUR. Anche in questo caso il proposito degli estensori è stato mirato non già alla costruzione di vere e proprie linee guida, ma a raccogliere in un unico compendio le principali evidenze scientifiche sull’epidemiologia, la diagnosi, l’inquadramento anatomo-patologico e biologico, la stadiazione, il trattamento e il follow-up delle neoplasie della vescica, che sono tra le patologie urologiche più frequenti e di maggiore rilevanza, anche sociale. Il materiale scientifico è ordinato in maniera sinottica, in modo da favorire la consultazione da parte di un’ampia utenza, non solo specialistica, ed è corredato dalle raccomandazioni scaturite dall’esperienza degli esperti qualificati che sono stati coinvolti nella estensione e nella revisione dei diversi capitoli. Tali raccomandazioni hanno lo scopo di consentire al lettore di costruire un proprio percorso diagnostico-terapeutico, alla luce anche delle evidenze fornite. Lasciamo pertanto al lettore il compito di integrare queste raccomandazioni con quanto proviene dalla personale esperienza e di conformarle con le linee guida già esistenti, in relazione anche alle specifiche esigenze. Vista la matrice di questa iniziativa, rappresentata dal CNR e MIUR, non potevano mancare nell’opera specifici riferimenti alle problematiche scientifiche, in grado di fornire spunti per le ricerche future. Certi che anche questa monografia potrà riscuotere lo stesso successo di quelle dedicate in precedenza al carcinoma della prostata e agli altri tumori solidi, sentiamo ancora una volta il dovere di esprimere la nostra gratitudine, per l’impegno e l’essenziale contributo, a tutti gli esperti coinvolti nel Gruppo di Studio e nel Gruppo di Consenso. -

Bladder Cancer

Clinical Practice in Urology Series Editor: Geoffrey D. Chisholm Titles in the series already published Urinary Diversion Edited by Michael Handley Ashken Chemotherapy and Urological Malignancy Edited by A. S. D. Spiers Urodynamics Paul Abrams, Roger Feneley and Michael Torrens Male Infertility Edited by T. B. Hargreave The Pharmacology of the Urinary Tract Edited by M. Caine Forthcoming titles in the series Urological Prostheses, Appliances and Catheters Edited by J. P. Pryor Percutaneous and Interventional Uroradiology Edited by Erich K. Lang Adenocarcinoma of the Prostate Edited by Andrew W. Bruce and John Trachtenberg Bladder Cancer Edited by E. J. Zingg and D. M. A. Wallace With 50 Figures Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg New York Tokyo E. J. Zingg, MD Professor and Chairman, Department of Urology, Univ~rsity of Berne, Inselspital, 3010 Berne, Switzerland D. M. A. Wallace, FRCS Consultant Urologist, Department of Urology, Queen Elizabeth Medical Centre, Birmingham, England Series Editor Geoffrey D. Chisholm, ChM, FRCS, FRCSEd Professor of Surgery, University of Edinburgh; Consultant Urological Surgeon, Western General Hospital, Edinburgh, Scotland ISBN -13: 978-1-4471-1364-5 e-ISBN -13: 978-1-4471-1362-1 DOI: 10.1007/978-1-4471-1362-1 Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Main entry under title: Bladder Cancer (Clinical Practice in Urology) Includes bibliographies and index. 1. Bladder - Cancer. I. Zingg, Ernst J. II. Wallace, D.M.A. (David Michael Alexander), 1946- DNLM: 1. Bladder Neoplasms. WJ 504 B6313 RC280.B5B632 1985 616.99'462 85-2572 ISBN-13:978-1-4471-1364-5 (U.S.) This work is subject to copyright. -

Primary Urethral Carcinoma

EAU Guidelines on Primary Urethral Carcinoma G. Gakis, J.A. Witjes, E. Compérat, N.C. Cowan, V. Hernàndez, T. Lebret, A. Lorch, M.J. Ribal, A.G. van der Heijden Guidelines Associates: M. Bruins, E. Linares Espinós, M. Rouanne, Y. Neuzillet, E. Veskimäe © European Association of Urology 2017 TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE 1. INTRODUCTION 3 1.1 Aims and scope 3 1.2 Panel composition 3 1.3 Publication history and summary of changes 3 1.3.1 Summary of changes 3 2. METHODS 3 2.1 Data identification 3 2.2 Review 3 2.3 Future goals 4 3. EPIDEMIOLOGY, AETIOLOGY AND PATHOLOGY 4 3.1 Epidemiology 4 3.2 Aetiology 4 3.3 Histopathology 4 4. STAGING AND CLASSIFICATION SYSTEMS 5 4.1 Tumour, Node, Metastasis (TNM) staging system 5 4.2 Tumour grade 5 5. DIAGNOSTIC EVALUATION AND STAGING 6 5.1 History 6 5.2 Clinical examination 6 5.3 Urinary cytology 6 5.4 Diagnostic urethrocystoscopy and biopsy 6 5.5 Radiological imaging 7 5.6 Regional lymph nodes 7 6. PROGNOSIS 7 6.1 Long-term survival after primary urethral carcinoma 7 6.2 Predictors of survival in primary urethral carcinoma 7 7. DISEASE MANAGEMENT 8 7.1 Treatment of localised primary urethral carcinoma in males 8 7.2 Treatment of localised urethral carcinoma in females 8 7.2.1 Urethrectomy and urethra-sparing surgery 8 7.2.2 Radiotherapy 8 7.3 Multimodal treatment in advanced urethral carcinoma in both genders 9 7.3.1 Preoperative platinum-based chemotherapy 9 7.3.2 Preoperative chemoradiotherapy in locally advanced squamous cell carcinoma of the urethra 9 7.4 Treatment of urothelial carcinoma of the prostate 9 8. -

Urology Clinical Privileges

Urology Clinical Privileges Name: _____________________________________________________ Effective from _______/_______/_______ to _______/_______/_______ ❏ Initial privileges (initial appointment) ❏ Renewal of privileges (reappointment) All new applicants should meet the following requirements as approved by the governing body, effective: February 18, 2015 Applicant: Check the “Requested” box for each privilege requested. Applicants are responsible for producing required documentation for a proper evaluation of current skill, current clinical activity, and other qualifications and for resolving any doubts related to qualifications for requested privileges. Please provide this supporting information separately. [Department/Program Head or Leaders/ Chief]: Check the appropriate box for recommendation on the last page of this form and include your recommendation for any required evaluation. If recommended with conditions or not recommended, provide the condition or explanation on the last page of this form. Current experience is an estimate of the level of activity below which a collegial discussion about support should be triggered. It is not a disqualifier. This discussion should be guided not only by the expectations and standards outlined in the dictionary but also by the risks inherent in the privilege being discussed and by similar activities that contribute to the skill under consideration. This is an opportunity to reflect with a respected colleague on one's professional practice and to deliberately plan an approach to skills maintenance. Other requirements • Note that privileges granted may only be exercised at the site(s) and/or setting(s) that have sufficient space, equipment, staffing, and other resources required to support the privilege. • This document is focused on defining qualifications related to competency to exercise clinical privileges. -

Icd-9-Cm (2010)

ICD-9-CM (2010) PROCEDURE CODE LONG DESCRIPTION SHORT DESCRIPTION 0001 Therapeutic ultrasound of vessels of head and neck Ther ult head & neck ves 0002 Therapeutic ultrasound of heart Ther ultrasound of heart 0003 Therapeutic ultrasound of peripheral vascular vessels Ther ult peripheral ves 0009 Other therapeutic ultrasound Other therapeutic ultsnd 0010 Implantation of chemotherapeutic agent Implant chemothera agent 0011 Infusion of drotrecogin alfa (activated) Infus drotrecogin alfa 0012 Administration of inhaled nitric oxide Adm inhal nitric oxide 0013 Injection or infusion of nesiritide Inject/infus nesiritide 0014 Injection or infusion of oxazolidinone class of antibiotics Injection oxazolidinone 0015 High-dose infusion interleukin-2 [IL-2] High-dose infusion IL-2 0016 Pressurized treatment of venous bypass graft [conduit] with pharmaceutical substance Pressurized treat graft 0017 Infusion of vasopressor agent Infusion of vasopressor 0018 Infusion of immunosuppressive antibody therapy Infus immunosup antibody 0019 Disruption of blood brain barrier via infusion [BBBD] BBBD via infusion 0021 Intravascular imaging of extracranial cerebral vessels IVUS extracran cereb ves 0022 Intravascular imaging of intrathoracic vessels IVUS intrathoracic ves 0023 Intravascular imaging of peripheral vessels IVUS peripheral vessels 0024 Intravascular imaging of coronary vessels IVUS coronary vessels 0025 Intravascular imaging of renal vessels IVUS renal vessels 0028 Intravascular imaging, other specified vessel(s) Intravascul imaging NEC 0029 Intravascular -

Bladder Cancer

PDF hosted at the Radboud Repository of the Radboud University Nijmegen The following full text is a publisher's version. For additional information about this publication click this link. http://hdl.handle.net/2066/19207 Please be advised that this information was generated on 2021-09-27 and may be subject to change. SUPERFICIAL BLADDER CANCER PROGNOSIS AND MANAGEMENT SUPERFICIAL BLADDER CANCER PROGNOSIS AND MANAGEMENT een wetenschappelijke proeve op het gebied van de Medische Wetenschappen Proefschrift ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor aan de Katholieke Universiteit Nijmegen op gezag van de Rector Magnificus Prof. dr. C. W. P. M. Blom, volgens besluit van het College van Decanen in het openbaar te verdedigen op woensdag 11 december 2002 des morgens om 11.00 uur precies door Necmettin Aydin Mungan geboren op 24 maart 1965 te Ankara Promotor : Prof. dr. F.M.J. Debruyne Co-Promotores : Dr. J.A. Witjes Dr. L.A.L.M. Kiemeney Manuscriptcommissie : Prof. dr. P. de Mulder Prof. dr. A.L.M. Lagro-Janssen Prof. dr. H. Boonstra Superficial bladder cancer: prognosis and management Necmettin Aydin Mungan ISBN 90-9016303-4 Printed by: ZES Tanitim, Ankara Cover design: Superficial bladder cancer Publication of this thesis was sponsored by: Onko&Koçsel Pharmaceuticals and Aventis Pasteur, Schering-Plough and Abbott Laboratories To my wife and kids Science is the truest guide for life, success and everything else in the world. Mustafa Kemal Ataturk Founder of Republic of Turkey CONTENTS Chapter Title Page 1 Introduction and outline of the thesis 9 2 Gender differences of (superficial) bladder cancer 21 3 Can sensitivity of voided urinary cytology or bladder 67 wash cytology be improved by the use of different urinary portions? 4 Detection of malignant cells: Can cytology be 79 replaced? 5 Comparison of the diagnostic value of the BTA Stat 101 Test with voided urinary cytology for detection of bladder cancer. -

Prostate Gland Biopsy

PROSTATE GLAND BIOPSY EUGENE F. POUTASSE, M.D. Department of Urology HE incidence of cancer of the prostate gland among men who have symp- Ttoms of bladder neck obstruction is about one out of five. The actual inci- dence of cancer is higher because many men are seen with symptoms unrelated to the urinary tract, such as bone pain, or who have evidence of the tumor without symptoms. It is the third most common cancer in men, exceeded only by cancer of the skin and alimentary tract in frequency of recognition. The chief methods by which a physician discovers prostatic cancer are rectal palpation of the gland, serum acid phosphatase determination, and roentgenographic study of the urinary tract and skeleton. These are satisfactory when the tumor has spread widely beyond the prostate. In this paper methods of biopsy for establishing the diagnosis when cancer of the prostate gland is suspected or when it is desirable to corroborate the clinical diagnosis of exten- sive cancer will be discussed. The actual diagnosis of cancer is made by micro- scopic definition, preferably on a block of tumor tissue. Under study is the cytologic examination of prostatic secretion for exfoliated tumor cells,1 which requires a great deal of time and experience. Methods of Biopsy A. Perineal. Exposure of the prostate gland through the perineum permits biopsy of any area of the gland which has been suspected of malignancy on rectal palpation. This approach is particularly useful because more than 90 per cent of all prostatic neoplasms arise in the posterior lobe accessible to rectal palpation. -

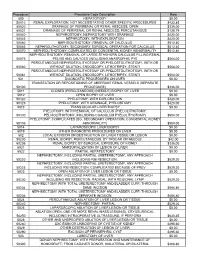

Procedure Procedure Code Description Rate 500

Procedure Procedure Code Description Rate 500 HEPATOTOMY $0.00 50010 RENAL EXPLORATION, NOT NECESSITATING OTHER SPECIFIC PROCEDURES $433.85 50020 DRAINAGE OF PERIRENAL OR RENAL ABSCESS; OPEN $336.00 50021 DRAINAGE OF PERIRENAL OR RENAL ABSCESS; PERCUTANIOUS $128.79 50040 NEPHROSTOMY, NEPHROTOMY WITH DRAINAGE $420.00 50045 NEPHROTOMY, WITH EXPLORATION $420.00 50060 NEPHROLITHOTOMY; REMOVAL OF CALCULUS $512.40 50065 NEPHROLITHOTOMY; SECONDARY SURGICAL OPERATION FOR CALCULUS $512.40 50070 NEPHROLITHOTOMY; COMPLICATED BY CONGENITAL KIDNEY ABNORMALITY $512.40 NEPHROLITHOTOMY; REMOVAL OF LARGE STAGHORN CALCULUS FILLING RENAL 50075 PELVIS AND CALYCES (INCLUDING ANATROPHIC PYE $504.00 PERCUTANEOUS NEPHROSTOLITHOTOMY OR PYELOSTOLITHOTOMY, WITH OR 50080 WITHOUT DILATION, ENDOSCOPY, LITHOTRIPSY, STENTI $504.00 PERCUTANEOUS NEPHROSTOLITHOTOMY OR PYELOSTOLITHOTOMY, WITH OR 50081 WITHOUT DILATION, ENDOSCOPY, LITHOTRIPSY, STENTI $504.00 501 DIAGNOSTIC PROCEDURES ON LIVER $0.00 TRANSECTION OR REPOSITIONING OF ABERRANT RENAL VESSELS (SEPARATE 50100 PROCEDURE) $336.00 5011 CLOSED (PERCUTANEOUS) (NEEDLE) BIOPSY OF LIVER $0.00 5012 OPEN BIOPSY OF LIVER $0.00 50120 PYELOTOMY; WITH EXPLORATION $420.00 50125 PYELOTOMY; WITH DRAINAGE, PYELOSTOMY $420.00 5013 TRANSJUGULAR LIVER BIOPSY $0.00 PYELOTOMY; WITH REMOVAL OF CALCULUS (PYELOLITHOTOMY, 50130 PELVIOLITHOTOMY, INCLUDING COAGULUM PYELOLITHOTOMY) $504.00 PYELOTOMY; COMPLICATED (EG, SECONDARY OPERATION, CONGENITAL KIDNEY 50135 ABNORMALITY) $504.00 5014 LAPAROSCOPIC LIVER BIOPSY $0.00 5019 OTHER DIAGNOSTIC PROCEDURES -

Ambulatory and Inpatient Procedures in the United States, 1996 Cdc-Pdf

Series 13 No. 139 Vital and Health Statistics From the CENTERS FOR DISEASE CONTROL AND PREVENTION / National Center for Health Statistics Ambulatory and Inpatient Procedures in the United States, 1996 November 1998 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National Center for Health Statistics Copyright Information All material appearing in this report is in the public domain and may be reproduced or copied without permission; citation as to source, however, is appreciated. Suggested citation Owings MF, Kozak LJ. Ambulatory and inpatient procedures in the United States, 1996. National Center for Health Statistics. Vital Health Stat 13(139). 1998. Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 97-42743 For sale by the U.S. Government Printing Office Superintendent of Documents Mail Stop: SSOP Washington, DC 20402-9328 Printed on acid-free paper. Vital and Health Statistics Ambulatory and Inpatient Procedures in the United States, 1996 Series 13: Data From the National Health Care Survey No. 139 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National Center for Health Statistics Hyattsville, Maryland November 1998 DHHS Publication No. (PHS) 99-1710 National Center for Health Statistics Edward J. Sondik, Ph.D., Director Jack R. Anderson, Deputy Director Jack R. Anderson, Acting Associate Director for International Statistics Lester R. Curtin, Ph.D., Acting Associate Director for Research and Methodology Jennifer H. Madans, Ph.D., Acting Associate Director for Analysis, Epidemiology, and Health Promotion P. Douglas Williams, Acting Associate Director for Data Standards, Program Development, and Extramural Programs Edward L. Hunter, Associate Director for Planning, Budget, and Legislation Jennifer H. -

Salvage Transrectal High-Intensity Focused Ultrasound Therapy for Patients with Recurrence of Vesico-Urethral Anastomosis After Radical Prostatectomy

Open Journal of Urology, 2019, 9, 167-179 https://www.scirp.org/journal/oju ISSN Online: 2160-5629 ISSN Print: 2160-5440 Salvage Transrectal High-Intensity Focused Ultrasound Therapy for Patients with Recurrence of Vesico-Urethral Anastomosis after Radical Prostatectomy Mutsuo Hayashi1*, Tetsutaro Hayashi2, Kiyotaka Oka1, Keisuke Goto2, Ryuhei Kanaoka1 1Department of Urology, Takanobashi Central Hospital, Hiroshima, Japan 2Department of Urology, Hiroshima University Hospital, Hiroshima, Japan How to cite this paper: Hayashi, M., Abstract Hayashi, T., Oka, K., Goto, K. and Kanaoka, R. (2019) Salvage Transrectal High-Intensity Background: Salvage radiotherapy has been used as the treatment for pa- Focused Ultrasound Therapy for Patients tients with local recurrence after radical prostatectomy. However, the therapy with Recurrence of Vesico-Urethral Anas- is time-consuming and it experiences adverse effects of some kind. Simple tomosis after Radical Prostatectomy. Open and less invasive treatment is highly anticipated. Objectives: To evaluate the Journal of Urology, 9, 167-179. https://doi.org/10.4236/oju.2019.910020 outcomes of salvage transrectal high-intensity focused ultrasound (HIFU) therapy for patients with localized recurrence of a vesicourethral anastomosis Received: September 18, 2019 (VUA) after radical prostatectomy. Material and methods: Sixteen patients Accepted: October 26, 2019 with suspected local recurrence of a VUA after prostatectomy were treated Published: October 29, 2019 with HIFU. All patients had prostate-specific antigen (PSA) failure (>0.2 Copyright © 2019 by author(s) and ng/ml), positive findings of a VUA with biopsy and/or MRI, TRUS and CT, Scientific Research Publishing Inc. and no distant metastasis by CT, MRI and bone scintigraphy before HIFU. -

Procedure Codes Exempt from the Recipient Outpatient Entitlement Maximum

Revised November 9, 2000 HCRA Handbook Appendix H PROCEDURE CODES EXEMPT FROM THE RECIPIENT OUTPATIENT ENTITLEMENT MAXIMUM Code Description 01.01 Cisternal puncture 01.02 Puncture of ventricular shunt tubing 01.15 Biopsy of skull 03.31 Spinal tap 03.91 Injection of anesthetic into spinal canal for analgesia 03.92 Injection of other agent in spinal canal 03.95 Spinal blood patch 04.43 Release of carpal tunnel 04.44 Tarsal tunnel release 04.49 Other peripheral nerve or ganglion decompression or lysis of adhesions 04.6 Transposition of cranial and peripheral nerves 04.74 Other anastomosis of cranial or peripheral nerve 04.75 Revision of previous repair of cranial and peripheral nerves 04.76 Repair of old traumatic injury of cranial and peripheral nerves 04.79 Other neuroplasty 04.81 Injection of anesthetic into peripheral nerve for analgesia 04.91 Neurectasis 04.92 Implantation or replacement of peripheral neurostimulator 04.93 Removal of peripheral neurostimulator 05.19 Other diagnostic procedures on sympathetic nerves or ganglia 06.11 Closed biopsy of thyroid gland Page H - 1 Revised November 9, 2000 HCRA Handbook Appendix H PROCEDURE CODES EXEMPT FROM THE RECIPIENT OUTPATIENT ENTITLEMENT MAXIMUM Code Description 06.12 Open biopsy of thyroid gland 06.31 Excision of lesion of thyroid 06.7 Excision of thyroglossal duct or tract 07.11 Closed biopsy of adrenal gland 08.01 Incision of lid margin 08.02 Severing of blepharorrhaphy 08.09 Other incision of eyelid 08.11 Biopsy of eyelid 08.19 Other diagnostic procedures on eyelid 08.20 Removal of -

Detecting Recurrent Prostate Cancer Using Multiparametric MRI, Influence of PSA and Gleason Grade Aradhana M

Venkatesan et al. Cancer Imaging (2021) 21:3 https://doi.org/10.1186/s40644-020-00373-4 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Detecting recurrent prostate Cancer using multiparametric MRI, influence of PSA and Gleason grade Aradhana M. Venkatesan1, Eniola Mudairu-Dawodu2, Cihan Duran3* , R. Jason Stafford4, Yuanqing Yan5, Wei Wei5 and Vikas Kundra1,6 Abstract Background: The utility of multiparametric MRI (mpMRI) in detecting suspected local recurrence post radical prostatectomy (RP) may be associated with PSA and Gleason grade. The purpose of the study was to evaluate the likelihood of detecting locally recurrent prostate cancer utilizing mpMRI in patients with suspected recurrence following radical prostatectomy (RP) parsed by PSA and Gleason grade. Methods: One hundred ninety five patients with suspected local recurrence were imaged on a 1.5 T MRI with torso array and endorectal coil in this retrospective study. mpMRI interpretations were stratified by PSA and lower (Gleason < 7) vs. higher grade tumors (Gleason 8–10). Recursive partitioning was used to determine whether mpMRI interpretations could be classified as positive or negative. Results: The majority of mpMRI interpretations in patients with lower Gleason grade tumors and PSA < 0.5 ng/mL were negative (68/78, 87.2%, p = 0.004). The majority of mpMRI interpretations in patients with higher Gleason grade tumors and PSA > 1.5 ng/mL were positive (8/9, 88.9%, p = 0.003). Findings were corroborated by recursive partitioning, which identified a PSA = 0.5 ng/ml in patients with lower grade tumors and a PSA = 1.5 ng/mL in patients with higher grade tumors as differentiating negative and positive mpMRIs.