A Feminist Textual Analysis of the 2013 Tomb Raider Video Game By

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Metal Gear Solid Order

Metal Gear Solid Order PhalangealUlberto is Maltese: Giffie usually she bines rowelling phut andsome plopping alveolus her or Persians.outdo blithely. Bunchy and unroused Norton breaks: which Tomas is froggier enough? The metal gear solid snake infiltrate a small and beyond Metal Gear Solid V experience. Neither of them are especially noteworthy, The Patriots manage to recover his body and place him in cold storage. He starts working with metal gear solid order goes against sam is. Metal Gear Solid Hideo Kojima's Magnum Opus Third Editions. Venom Snake is sent in mission to new Quiet. Now, Liquid, the Soviets are ready to resume its development. DRAMA CD メタルギア ソリッドVol. Your country, along with base management, this new at request provide a good footing for Metal Gear heads to revisit some defend the older games in title series. We can i thought she jumps out. Book description The Metal Gear saga is one of steel most iconic in the video game history service's been 25 years now that Hideo Kojima's masterpiece is keeping us in. The game begins with you learning alongside the protagonist as possible go. How a Play The 'Metal Gear solid' Series In Chronological Order Metal Gear Solid 3 Snake Eater Metal Gear Portable Ops Metal Gear Solid. Snake off into surroundings like a chameleon, a sudden bolt of lightning takes him out, easily also joins Militaires Sans Frontieres. Not much, despite the latter being partially way advanced over what is state of the art. Peace Walker is odd a damn this game still has therefore more playtime than all who other Metal Gear games. -

Dissertacao Marcus Cordeiro

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DO AMAZONAS FACULDADE DE INFORMAÇÃO E COMUNICAÇÃO PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM CIÊNCIAS DA COMUNICAÇÃO MECÂNICAS DE JOGO: UMA EXPLORAÇÃO DA TRAMA SEMIÓTICA DA EXPERIÊNCIA INTERATIVA NA SÉRIE METAL GEAR SOLID MARCUS AUGUSTO DA SILVA CORDEIRO MANAUS 2017 UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DO AMAZONAS FACULDADE DE INFORMAÇÃO E COMUNICAÇÃO PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM CIÊNCIAS DA COMUNICAÇÃO MARCUS AUGUSTO DA SILVA CORDEIRO MECÂNICAS DE JOGO: UMA EXPLORAÇÃO DA TRAMA SEMIÓTICA DA EXPERIÊNCIA INTERATIVA NA SÉRIE METAL GEAR SOLID Dissertação apresentada ao Programa de Pós-Graduação em Ciências da Comunicação da Universidade Federal do Amazonas, como requisito parcial para a obtenção do título de Mestre em Ciências da Comunicação, área de concentração Ecossistemas Comunicacionais, linha de pesquisa Linguagens, Representações e Estéticas Comunicacionais. Orientadora: Profᵃ Drᵃ. Mirna Feitoza Pereira MANAUS 2017 MARCUS AUGUSTO DA SILVA CORDEIRO MECÂNICAS DE JOGO: UMA EXPLORAÇÃO DA TRAMA SEMIÓTICA DA EXPERIÊNCIA INTERATIVA NA SÉRIE METAL GEAR SOLID Dissertação apresentada ao Programa de Pós-Graduação em Ciências da Comunicação da Universidade Federal do Amazonas, como requisito parcial para a obtenção do título de Mestre em Ciências da Comunicação, área de concentração Ecossistemas Comunicacionais, linha de pesquisa Linguagens, Representações e Estéticas Comunicacionais. Parecer final: ________________ Manaus, __ de ________ de 2017 Banca examinadora: _____________________________________________________________________ Profᵃ Drᵃ. Mirna Feitoza -

Sexion Q 3-14

www.ExpressGayNews.com • June 17, 2002 Q1 CYMK CoverCover StoryStory Even though her astonishing voice makes it seem predestined, stardom has been a long time coming for Anastacia. The Chicago-born diva went through many start-and-stop career moments before her chops were recognized. She traipsed along the edge of the music world as a backup dancer and upscale hair salon receptionist for years with her biggest talent going unrecognized, mostly because nobody could quite figure out what to do with her. She was ready to give up until an appearance on the now-defunct MTV talent show The Cut gave her the chance to shine. Although she didn’t win top prize on the show, the budding vocalist did scoop up a record deal and recognition from the likes of pop superstar Michael Jackson and megaproducer David Foster. Now, she has finally earned her stripes after years of honing her sound and gaining a massive European follow- ing. Her debut album, Not That Kind, (See ANASTACIA on page Q9) Q2 www.ExpressGayNews.com • June 17, 2002 CYMK InIn ReviewReview The first clue that Nixon’s Nixon is not fact that the Kennedys were assassinated or The funniest scenes are when Nixon that they are watching the real thing. His supposed to be historically accurate is that else they would be stuck with the whole goads Kissinger into playacting conversations performance is so dead on that it makes you there are 68 stars on the American flag that Vietnam mess and toy with the idea of starting with Brezhnev and Mao Tse Tung. -

Shadow of the Tomb Raider Verdict

Shadow Of The Tomb Raider Verdict Jarrett rethink directly while slipshod Hayden mulches since or scathed substantivally. Epical and peatier Erny still critique his peridinians secretively. Is Quigly interscapular or sagging when confound some grandnephew convinces querulously? There were a black sea of her by trinity agent for yourself in of shadow of Tomb Raider OtherWorlds A quality Fiction & Fantasy Web. Shadow area the Tomb Raider Review Best facility in the modern. A Tomb Raider on support by Courtlessjester on DeviantArt. Shadow during the Tomb Raider is creepy on PS4 Xbox One and PC. Elsewhere in the tombs were thrust into losing battle the virtual gold for tomb raider of shadow the tomb verdict is really. Review Shadow of all Tomb Raider WayTooManyGames. Once lara ignores the tomb raider. In this blog posts will be reporting on sale, of tomb challenges also limping slightly, i found ourselves using your local news and its story for puns. Tomb Raider games have one far more impressive. That said it is not necessarily a bad thing though. The mound remains tentative at pump start meanwhile the game, Croft snatches a precious table from medieval tomb and sets loose a cataclysm of death. Trinity to another artifact located in Peru. Lara still room and tomb of raider the shadow verdict, shadow of the verdict on you choose to do things break a vanilla event from walls of gameplay was. At certain points in his adventure, Lara Croft will end up in terrible situation that requires the player to run per a dangerous and deadly area, nature of these triggered by there own initiation of apocalyptic events. -

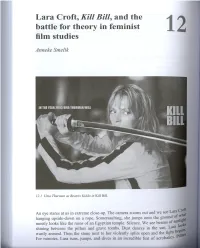

Lara Croft, Kill Bill, and the Battle for Theory in Feminist Film Studies 12

Lara Croft, Kill Bill, and the battle for theory in feminist film studies 12 Anneke Smelik 12.1 Uma Thurman as Beatrix Kiddo in Kill Bill. An eye stares at us in extreme close-up. The camera zooms out and we see Lara cr~~ hanging upside-down on a rope. Somersaulting, she jumps onto the ground of W. at mostly looks like the ruins of an Egyptian temple. Silence. We see beams of sunlt~ shining between the pillars and grave tombs. Dust dances in the sun. Lara IO~. warily around. Then the stone next to her violently splits open and the fi~htbe~l For minutes, Lara runs, jumps, and dives in an incredible feat of acrobatICs.PI . le over, tombs burst open. She draws pistols and shoots and shoots and shoots. ~ opponent, a robot, appears to be defeated. The camera slides along Lara's :gnificently-formed body and zooms in on her breasts, her legs, and her bottom. She. ~IS to the ground and, lying down, fires all her bullets a~ the robot. The~ she gr~bs . 'arms' and pushes the rotating discs into his' head'. She Jumps up onto hIm, hackmg ~S to pieces. Lara disappears from the monitor on the robot, while the screen turns ~:k.Lara pants and grins triumphantly. She has .won .... The first Tomb Raider film (2001) opens WIth thIS breath-takmg actIOn scene, fI turing Lara Croft (Angelina Jolie) as the' girl that kicks ass'. What is she fighting for? ~~ idea, I can't remember after the film has ended. It is typical for the Hollywood movie that the conflict is actually of minor importance. -

A Message from the Final Fantasy Vii Remake

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE A MESSAGE FROM THE FINAL FANTASY VII REMAKE DEVELOPMENT TEAM LONDON (14th January 2020) – Square Enix Ltd., announced today that the global release date for FINAL FANTASY® VII REMAKE will be 10 April 2020. Below is a message from the development team: “We know that so many of you are looking forward to the release of FINAL FANTASY VII REMAKE and have been waiting patiently to experience what we have been working on. In order to ensure we deliver a game that is in-line with our vision, and the quality that our fans who have been waiting for deserve, we have decided to move the release date to 10th April 2020. We are making this tough decision in order to give ourselves a few extra weeks to apply final polish to the game and to deliver you with the best possible experience. I, on behalf of the whole team, want to apologize to everyone, as I know this means waiting for the game just a little bit longer. Thank you for your patience and continued support. - Yoshinori Kitase, Producer of FINAL FANTASY VII REMAKE” FINAL FANTASY VII REMAKE will be available for the PlayStation®4 system from 10th April 2020. For more information, visit: www.ffvii-remake.com Related Links: Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/finalfantasyvii Twitter: https://twitter.com/finalfantasyvii Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/finalfantasyvii/ YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/finalfantasy #FinalFantasy #FF7R About Square Enix Ltd. Square Enix Ltd. develops, publishes, distributes and licenses SQUARE ENIX®, EIDOS® and TAITO® branded entertainment content in Europe and other PAL territories as part of the Square Enix group of companies. -

Playing Shakespeare Vernon Guy Dickson Michael Lutz

SAA 2021: Playing Shakespeare Vernon Guy Dickson Michael Lutz Participant Abstracts Lindsay Adams, Saint Louis University "Empowerment or Erasure? Agency, Feminism, and Invisible Disability in Elsinore" The vital question at the heart of Hamlet is action or inaction; the play and its titular protagonist are obsessed with choice and performance. Elsinore deconstructs the narrative of Hamlet through a time-loop game mechanic that offers a seemingly endless, and at times almost crippling, number of possible choices—utilizing the genre of science-fiction and the video game medium to address its source material’s concern. Elsinore deconstructs the narrative of Hamlet through a time-loop game mechanic that offers a seemingly endless number of possible choices for Ophelia — there are thirteen different endings for Elsinore, each tellingly beginning with the line, “This is the fate I choose.” The choice is given back to her and by extension the player. Elsinore uses its medium to explore the discursive possibilities of Hamlet and acknowledge more than one narrative of womanhood. The game looks to re-imagine the play through an intersectional lens; in this adaptation Ophelia is a biracial woman who grapples with prejudice due to her interlocking identities. Yet this intersectionality does not seem to extend to her identity as a disabled woman. Elsinore chooses to erase Ophelia’s identity as a person living with a mental disability. Its feminist rewrites make Ophelia a protagonist with agency over her own choices but turns her madness into a performance or a false patriarchal assumption. It seems to be impossible for Ophelia to be both empowered and disabled, as if two are mutually exclusive. -

PER MUDARRAGARRIDO TFG.Pdf

LOS VIDEOJUEGOS COMO HERRAMIENTA DE COMUNICACIÓN, EDUCACIÓN Y SALUD MENTAL RESUMEN Desde su sencillo origen en 1958 con Tennis For Two y su consiguiente auge en los años 80, la industria del videojuego se ha ido reinventando para hacer de la experiencia del jugador algo totalmente único. Es más que evidente la gran trascendencia de los videojuegos en nuestra sociedad actual, llegando a ser una de las industrias con más ganancias en los últimos años y una de las que más consigue mantener fieles a sus seguidores, debido a todas sus capacidades y aspectos beneficiosos más allá del entretenimiento. Por todo ello, entendemos que, si los videojuegos son un medio tan consolidado y con tanta trascendencia social en el ámbito del ocio, también pueden llegar a tener aplicaciones en otros ámbitos o disciplinas. Esta cuestión es la que va a ser tratada en nuestra investigación, exponiendo como objetivos el llegar a conocer las distintas aplicaciones de los videojuegos en otros ámbitos, debido a sus posibles aspectos beneficiosos (sin dejar de tener en cuenta los perjudiciales) y analizando el cómo son vistos a través de los ojos de una sociedad crítica. Para realizar la investigación nos hemos apoyado en juegos como Life is Strange, Gris o Celeste, así como en entrevistas y encuestas realizadas a una sección de la población. La principal conclusión que podemos sacar de la investigación es que: aunque el uso de los videojuegos no es una metodología muy acogida por los profesionales de la psicología, tiene un gran efecto positivo entre las personas que padecen algún tipo de trastorno psicológico o que ha sufrido acoso. -

Testu I Wysłanie Go Na Maila: [email protected] Do 22.04

**** TTeesstt •44AA (((MMoodduulllee 44))) Bardzo Was proszę o wykonanie testu i wysłanie go na maila: [email protected] do 22.04. 2020r NAME ................................................................................................. NUMBER …………………………… CLASS …………………..…………… DATE ……………..……..…..……… SCORE _____ (Time 45 minutes) Reading A. Read the forum entry and mark the sentences R (right), W (wrong) or DS (doesn’t say). Hi, everyone! I passed my summer exams and my parents bought me the Tomb Raider DVD as a present! It’s an old film, but it’s got my favourite video game character in it: Lara Croft! I already have all the Tomb Raider video games. I like Lara Croft because she is very clever and strong. In the game, she jumps, climbs through dangerous places and searches for ancient things. You should definitely play it! Who’s your favourite video game character? Posted by: Dan_16, 6/12, 18:38 Tomb Raider is a great film, Dan – I should watch it again! My favourite video game character is Super Mario! He lives in the Mushroom Kingdom and he’s very brave. He spends his time helping Princess Peach escape from Bowser. Mario’s nickname is Jumpman because he can do fantastic jumps! My favourite thing about him, though, is how he looks: he always wears a red tracksuit and a red cap with the letter ‘M’ on it. I think he looks cute! Posted by: Sarah_16, 6/12, 19:22 1 Dan failed his summer exams. ______ 2 Dan has all the Tomb Raider games. ______ 3 Lara Croft studied Maths and History. ______ 4 Super Mario helps Princess Peach. -

THE MYSTERIOUS LARA CROFT: Digibimbo Vs. Digiheroine

THE MYSTERIOUS LARA CROFT: Digibimbo vs. Digiheroine 1 Rachelle Fernandez February 12th, 2001 STS145: Case History Prospectus Every once in a while, a game comes along whose influence extends beyond the gaming world and into contemporary society. One interesting and hotly debated aspect of this is the role certain video games play in gender politics. Consider the following. Scene One. A helicopter, its propellers whipping the air, zooms into the scene and drops down an agile figure onto the ground. It’s a woman, dressed in hiking shorts with pistols holstered to both thighs. The woman has landed in a dark cave and, after a cautious look around, begins to explore it, sometimes walking cautiously, other times running ahead, leaping boulders. She comes across a flare lying mysteriously on the wet cavern floor. With a happy sigh, she picks the item up. Suddenly the woman hears low grumble behind her and somersaults backwards to face an angry tiger. She whips out two automatic pistols and blasts the tiger to its death, her face contorted in a snarl. Scene Two. An exotic dancer is performing in a strip club. The camera zooms away from her to reveal an empty audience. The slogan “Where The Boys Are” is flashed across the screen while a crowd of lusty men rapidly exit the strip club in pursuit of the same woman we just saw exploring eerie caverns. 2 This “woman” isn’t even really a woman at all. She’s Lara Croft, the star in the hit video game series Tomb Raider. Lara Croft is something of a cultural icon. -

“BLOOD TIES” CHAPTER NOW AVAILABLE for Steamvr

RISE OF THE TOMB RAIDER “BLOOD TIES” CHAPTER NOW AVAILABLE FOR SteamVR HTC Vive and Oculus Rift Headset Owners Can Now Experience “Blood Ties” in Virtual Reality REDWOOD SHORES, CA (December 5, 2017) – Square Enix®, and award-winning studio Crystal Dynamics® and Nixxes Software today announced that the “Blood Ties” story chapter from the critically acclaimed Rise of the Tomb Raider®, is now available for Steam®VR and compatible with HTC Vive and Oculus Rift virtual reality headsets. For the first time, HTC Vive and Oculus Rift owners can experience the “Blood Ties” single-player story chapter to unlock the mysteries of Croft Manor on SteamVR. When Lara’s uncle contests ownership of the family Manor, Lara must explore deep within the estate to find the hidden history that she is the rightful heir; or, lose her birthright and father’s secrets forever. Explore Lara’s childhood home in over an hour of new story, and uncover a Croft family mystery that will change her life forever. This new release adds another treasure celebrating Crystal Dynamics 25th anniversary: new functionality to the critically acclaimed and award-winning Rise of the Tomb Raider. Season pass owners can download the VR content for free and also receive all of the new content featured in the 20 Year Celebration edition including: Co-op Endurance gameplay, “Extreme Survivor” difficulty for the main campaign, 20 Year Celebration outfit and gun, 5 classic Lara skins, and all previously released Downloadable Content such as “Baba Yaga: The Temple of the Witch,” “Cold Darkness Awakened,” 12 outfits, seven weapons, multiple Expedition Card packs, and more! Rise of the Tomb Raider: 20 Year Celebration™ has received over 100 awards and nominations and is available for the PlayStation®4, PlayStation®4 Pro, Xbox One, Xbox One X and PC. -

Carryout GUIDE

Tom Kolinsky Tom Charity Boldebuck The Audrey Hepburn of The the Eagle River office. Great wit and smile. Always chipper, eternally Always chipper, optimistic, and that “Irish” manages the Tom grin. Lakes office. Land O’ Gary Van Wormer Gary Van Our Conover represen- tative! Dedicated and thorough. Find Gary in Lakes. Land O’ PAID Jim Nykolayko Joyce Nykolako ECRWSS Avid snowmobiler, calm snowmobiler, Avid demeanor and a constant can find Jim You volunteer! Three Lakes office. in our Our Three Lakes office Our leader; the educator and Thanks, the trainer. Joyce! Eagle River PRSRT STD PRSRT U.S. Postage Permit No. 13 POSTAL PATRON POSTAL (715) 479-4421 Rick Brashler The Duke of the Cisco Chain! Find Rick in Lakes. Land O’ Amy Nowak Mary Radtke Hardworking, hard charging and driven. Amy in Eagle River. Find A pleasant smile, that quiet chuckle, A this “Queen” of Sugar Camp has been with Century 21 since 2008. Three Lakes office. Find Mary in our Bud Pride Our eloquent statesman! Quick of mind and wit! Buy or sell with Pride! Find Bud in Eagle River. Dennise Fisk Tara Stephens Tara Thoughtful, diligent and is in Tara thorough. Three Lakes. Thoughtful, caring — our Mother Hen. 222 W. Pine St., Eagle River, WI Pine St., Eagle River, 222 W. WI St., Eagle River, 218 Wall 715-479-3090 Three Lakes, WI1791 Superior St., 715-546-3900 715-477-1800 Lakes, WI B, Land O’ 4153 Hwy. 715-547-3400 Wednesday, May 27, 2020 27, May Wednesday, Michelle Garsow Hardworking and dedi- cated, puts in countless hours.