Migrations and Conservation Implications of Post-Nesting Green Turtles from Gielop Island, Ulithi Atoll, Federated States of Micronesia*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

IOM Micronesia

IOM Micronesia Federated States of Micronesia Republic of the Marshall Islands Republic of Palau Newsletter, July 2018 - April 2019 IOM staff Nathan Glancy inspects a damaged house in Chuuk during the JDA. Credit: USAID, 2019 Typhoon Wutip Destruction Typhoon Wutip passed over Pohnpei, Chuuk, and Yap States, FSM between 19 and 22 February with winds of 75–80 mph and gusts of up to 100 mph. Wutip hit the outer islands of Chuuk State, including the ‘Northwest’ islands (Houk, Poluwat, Polap, Tamatam and Onoun) and the ‘Lower and ‘Middle’ Mortlocks islands, as well as the outer islands of Yap (Elato, Fechailap, Lamotrek, Piig and Satawal) before continuing southwest of Guam and slowly dissipating by the end of February. FSM President, H.E. Peter M. Christian issued a Declaration of Disaster on March 11 and requested international assistance to respond to the damage caused by the typhoon. Consistent with the USAID/FEMA Operational Blueprint for Disaster Relief and Reconstruction in the Federated States of Micronesia (FSM) and the Republic of the Marshall Islands (RMI), a Joint Damage Assessment (JDA) was carried out by representatives of USAID, OFDA, FEMA and the Government of FSM from 18 March to 4 April, with assistance from IOM. The JDA assessed whether Wutip damage qualifies for a US Presidential Disaster Declaration. The JDA found Wutip had caused damage to the infrastructure and agricultural production of 30 islands, The path of Typhoon Wutip Feb 19-22, 2019. Credit: US JDA, 2019. leaving 11,575 persons food insecure. Response to Typhoon Wutip IOM, with the support of USAID/OFDA, has responded with continued distributions of relief items stored in IOM warehouses such as tarps, rope and reverse osmosis (RO) units to affected communities on the outer islands of Chuuk, Yap and Pohnpei states. -

A Companion to Contemporary Documentary Filn1

A Companion to Contemporary Documentary Filn1 Edited by Alexandra Juhasz and Alisa Lebow WI LEY Blackwell 2 o ,�- This edition first published 2015 © 2015 John Wiley & Sons, Inc, excepting Chapter 1 © 2014 by the Regents of the University of Minnesota and Chapter 19 © 2007 Wayne State University Press Registered Office John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, UK Contents Editorial Offices 350 Main Street, Malden, MA 02148-5020, USA 9600 Garsington Road, Oxford, OX4 2DQ, UK The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, UK For details of our global editorial offices,for customer services, and for informationabout how to apply for permission to reuse the copyright material in this book please see our website at www.wiley.com/wiley-blackwell. The right of Alexandra Juhasz and Alisa Lebow to be identifiedas the authors of the editorial material in this work has been asserted in accordance with the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, except as permitted by the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, without the prior permission of the publisher. Wiley also publishes its books in a variety of electronic formats. Some content that appears in print Notes on Contributors ix may not be available in electronic books. Introduction: A World Encountered 1 Designations used by companies to distinguish their products are often claimed as trademarks. All Alexandra Juhasz and Alisa Lebow brand names and product names used in this book are trade names, service marks, trademarks or registered trademarks of their respective owners. -

Ascertain Which Aspects of the Aboriginal Belief Structure, As 2) An

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 066 365 SO 002 935 AUTHOR Mitchell, Roger E. TITLE Oral Traditions of Micronesians as an Index to Culture Change Reflected in Micronesian College Graduates. Final Report. INSTITUTION Wisconsin State Univ.,Eau Claire. SPONS AGENCY Office of Education (DHEW), Washington, D.C. Bureau of Research. BUREAU NO BR-O-E-162 PUB DATE 1 Mar 72 GRANT OEG-5-71-0007-509 NOTE 27p. EDRS PRICE MF-$0 .65 BC-$3. 29 DESCRIPTORS *Acculturation; Biculturalism; *College Students; Cultural Background; Cultural Differences; *Cultural Factors; *Folk Culture; Interviews; *Oral Communication; Values IDENTIFIERS *Micronesians ABSTRACT The study on which this final report is based focused on selected Micronesian students at the University of Guam who, after receiving their degrees, will return to their home islands to assume positions requiring them to function as intermediaries between the American and Micronesian approaches of life. Interviews with these students and with less-educated fellow islanders were taped to: 1) ascertain which aspects of the aboriginal belief structure, as preserved in oral tradition, have been most resistant to change; and, 2) an attempt to establish if the students are fairly representative of their traditional belief and value system despite their American-sponsored educations. Some of the findings were: that student belief in, and knowledge of the old mythological and cosmological constructs was generally low; that belief was high in magic, native medicine, and spirits; and that young and old alike were receptive to attempts at cultural preservations. The report contains a summary of the study, a discussion of study background, a description of methods used in collection of the folktales, analyses of the oral traditions, 16 references, and a bibliography containing over 100 entries. -

Renewable Energy Development Project

Project Number: 49450-023 November 2019 Pacific Renewable Energy Investment Facility Federated States of Micronesia: Renewable Energy Development Project This document is being disclosed to the public in accordance with ADB’s Access to Information Policy. CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS The currency unit of the Federated States of Micronesia is the United States dollar. ABBREVIATIONS ADB – Asian Development Bank BESS – battery energy storage system COFA – Compact of Free Association DOFA – Department of Finance and Administration DORD – Department of Resources and Development EIRR – economic internal rate of return FMR – Financial Management Regulations FSM – Federated States of Micronesia GDP – gross domestic product GHG – greenhouse gas GWh – gigawatt-hour KUA – Kosrae Utilities Authority kW – kilowatt kWh – kilowatt-hour MW – megawatt O&M – operation and maintenance PAM – project administration manual PIC – project implementation consultant PUC – Pohnpei Utilities Corporation TA – technical assistance YSPSC – Yap State Public Service Corporation NOTE In this report, “$” refers to United States dollars unless otherwise stated. Vice-President Ahmed M. Saeed, Operations 2 Director General Ma. Carmela D. Locsin, Pacific Department (PARD) Director Olly Norojono, Energy Division, PARD Team leader J. Michael Trainor, Energy Specialist, PARD Team members Tahmeen Ahmad, Financial Management Specialist, Procurement, Portfolio, and Financial Management Department (PPFD) Taniela Faletau, Safeguards Specialist, PARD Eric Gagnon, Principal Procurement Specialist, -

Nautical Cartography and Traditional Navigation in Oceania

13 · Nautical Cartography and Traditional Navigation in Oceania BEN FINNEY MENTAL CARTOGRAPHY formal images and their own sense perceptions to guide their canoes over the ocean. The navigational practices of Oceanians present some The idea of physically portraying their mental images what of a puzzle to the student of the history of carto was not alien to these specialists, however. Early Western graphy. Here were superb navigators who sailed their ca explorers and missionaries recorded instances of how in noes from island to island, spending days or sometimes digenous navigators, when questioned about the islands many weeks out of sight of land, and who found their surrounding their own, readily produced maps by tracing way without consulting any instruments or charts at sea. lines in the sand or arranging pieces of coral. Some of Instead, they carried in their head images of the spread of these early visitors drew up charts based on such ephem islands over the ocean and envisioned in the mind's eye eral maps or from information their informants supplied the bearings from one to the other in terms of a con by word and gesture on the bearing and distance to the ceptual compass whose points were typically delineated islands they knew. according to the rising and setting of key stars and con Furthermore, on some islands master navigators taught stellations or the directions from which named winds their pupils a conceptual "star compass" by laying out blow. Within this mental framework of islands and bear coral fragments to signify the rising and setting points of ings, to guide their canoes to destinations lying over the key stars and constellations. -

Federal Register/Vol. 67, No. 115/Friday, June 14

Federal Register / Vol. 67, No. 115 / Friday, June 14, 2002 / Notices 40929 Program; 83.548, Hazard Mitigation Grant also be limited to 75 percent of the total Agency, Washington, DC 20472, (202) Program.) eligible costs. 646–2705 or [email protected]. Further, you are authorized to make Joe M. Allbaugh, SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION: The notice Director. changes to this declaration to the extent allowable under the Stafford Act. of a major disaster declaration for the [FR Doc. 02–15048 Filed 6–13–02; 8:45 am] State of Missouri is hereby amended to BILLING CODE 6718–02–P Notice is hereby given that pursuant include the following areas among those to the authority vested in the Director of areas determined to have been adversely the Federal Emergency Management affected by the catastrophe declared a FEDERAL EMERGENCY Agency under Executive Order 12148, I major disaster by the President in his MANAGEMENT AGENCY hereby appoint William L. Carwile III of declaration of May 6, 2002: the Federal Emergency Management [FEMA–1417–DR] Cedar, Crawford, Laclede, McDonald, Agency to act as the Federal Oregon, Ozark, Shannon, Ste. Genevieve, Federated States of Micronesia; Major Coordinating Officer for this declared Stone, Vernon, and Wright Counties for Disaster and Related Determinations disaster. Public Assistance (already designated for I do hereby determine the following Individual Assistance). AGENCY: Federal Emergency areas of the Federated States of Dekalb, Lincoln, Maries, Marion, Miller, Management Agency (FEMA). Micronesia to have been affected Osage, Phelps, Pike, Pulaski, Ralls, and Ray ACTION: Notice. adversely by this declared major Counties for Public Assistance. disaster: (The following Catalog of Federal Domestic SUMMARY: This is a notice of the Yap State for Public Assistance. -

The Micronesia Compendium a Compilation of Guidebook References and Cruising Reports Covering the Federated States of Micronesia and Palau

The Micronesia Compendium A Compilation of Guidebook References and Cruising Reports Covering the Federated States of Micronesia and Palau IMPORTANT: USE ALL INFORMATION IN THIS DOCUMENT AT YOUR OWN RISK!! Rev 2016.4 – August 20, 2016 We welcome updates to this guide! (especially for places we have no cruiser information on) Email Soggy Paws at sherry –at- svsoggypaws –dot- com. You can also contact us on Sailmail at WDI5677 The current home of the official copy of this document is http://svsoggypaws.com/files/ If you found it posted elsewhere, there might be an updated copy at svsoggypaws.com. Revision Log Many thanks to all who have contributed over the years!! Rev Date Notes A.0 28-Oct-2013 Initial version, still very rough at this point!! Moved some "outer atolls" around. Added some stuff gleaned from the RCC Pilotage Foundation. I am still not A.1 17-Nov-2013 clear where and who each of the outer atolls that other cruisers have mentioned actually fall in location and jurisdiction. I will resolve this in the next edition. More on Pohnpei and Kosrae, as we prepare to go there, A.2 26-Jan-2014 plus Carina's update on Lukunor. Added Downtime, Savannah's Pohnpei, Swingin' on a Star A.3 14-Feb-2014 and Carina. Broke the "between major islands" sections into separate sections. Brickhouse Inputs on West Fayu, Elato, Olimarao, and A.4 15-Feb-2014 Lorelei inputs on Losap Added section on Traditional Navigation on the Caroline A.5 17-Feb-2014 Islands. Added bits from US Sailing Directions (Pub 126). -

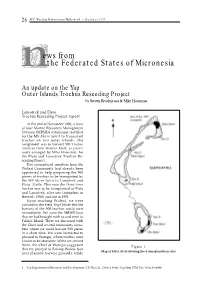

An Update on the Yap Outer Islands Trochus Reseeding Project by Steven Retalmawai & Mike Hasurmai

26 SPC Trochus Information Bulletin #5 – October 1997 ews from nthe Federated States of Micronesia An update on the Yap Outer Islands Trochus Reseeding Project by Steven Retalmawai & Mike Hasurmai Lamotrek and Elato Trochus Reseeding Project report At the end of November 1996, a team of four Marine Resources Management Division (MRMD) technicians travelled on the MS Micro Spirit to transplant trochus on two outer islands. The assignment was to harvest 500 Trochus niloticus from Woleai Atoll, as previ- ously arranged by Mike Hasurmai, for the Elato and Lamotrek Trochus Re- seeding Project. Five unemployed members from the Woleai Community had already been appointed to help preparing the 500 pieces of trochus to be transported by the MS Micro Spirit to Lamotrek and Elato Atolls. This was the third time trochus was to be transplanted to Elato and Lamotrek, after one transplant in the early 1980s and one in 1991. Upon reaching Woleai, we were advised by the Field Trip Officer that the harvest of the 500 trochus could start immediately. We used the MRMD boat that we had brought with us and went to Falalus Island. There we discussed with the Chief and several community mem- bers where we could harvest 500 pieces in a short time. We were instructed to proceed to Wotegai, where trochus were known to be abundant. When we arrived there, the Chief of Wotegai suggested Figure 1 that we proceed to Falalop Woleai (our Map of Elato Atoll showing the 4 transplantation sites next planned harvest ground), while 1 Yap Department of Resources and Development, P.O. -

This Keyword List Contains Pacific Ocean (Excluding Great Barrier Reef)

CoRIS Place Keyword Thesaurus by Ocean - 3/2/2016 Pacific Ocean (without the Great Barrier Reef) This keyword list contains Pacific Ocean (excluding Great Barrier Reef) place names of coral reefs, islands, bays and other geographic features in a hierarchical structure. The same names are available from “Place Keywords by Country/Territory - Pacific Ocean (without Great Barrier Reef)” but sorted by country and territory name. Each place name is followed by a unique identifier enclosed in parentheses. The identifier is made up of the latitude and longitude in whole degrees of the place location, followed by a four digit number. The number is used to uniquely identify multiple places that are located at the same latitude and longitude. This is a reformatted version of a list that was obtained from ReefBase. OCEAN BASIN > Pacific Ocean OCEAN BASIN > Pacific Ocean > Albay Gulf > Cauit Reefs (13N123E0016) OCEAN BASIN > Pacific Ocean > Albay Gulf > Legaspi (13N123E0013) OCEAN BASIN > Pacific Ocean > Albay Gulf > Manito Reef (13N123E0015) OCEAN BASIN > Pacific Ocean > Albay Gulf > Matalibong ( Bariis ) (13N123E0006) OCEAN BASIN > Pacific Ocean > Albay Gulf > Rapu Rapu Island (13N124E0001) OCEAN BASIN > Pacific Ocean > Albay Gulf > Sto. Domingo (13N123E0002) OCEAN BASIN > Pacific Ocean > Amalau Bay (14S170E0012) OCEAN BASIN > Pacific Ocean > Amami-Gunto > Amami-Gunto (28N129E0001) OCEAN BASIN > Pacific Ocean > American Samoa > American Samoa (14S170W0000) OCEAN BASIN > Pacific Ocean > American Samoa > Manu'a Islands (14S170W0038) OCEAN BASIN > -

Best of Micronesia: Rabaul to Palau Field Report

Best of Micronesia Rabaul to Palau March 3 - 20, 2019 Gaferut Island Chuuk (Truk) Island Ifalik Lamotrek Sorol Pulap Koror, Ngulu Atoll Island Oroluk Atoll Island Atoll Palau Atoll Pohnpei Island FEDERATED STATES OF MICRONESIA PACIFIC OCEAN Nukuoro Kapingamarangi Rabaul PAPUA NEW GUINEA Port Moresby Wednesday, March 6, 2019 Port Moresby, Papua New Guinea / Rabaul / Embark Caledonian Sky Today marked the first day of our voyage through Micronesia! We departed theAirways Hotel— where the Vue Restaurant’s delightful breakfast was only surpassed by the panoramic vista of the Owen Stanley Ranges—for Jacksons International Airport and our charter flight to Rabaul. Taking off just after 10:00 AM, we turned northeast, rose over the Owen Stanley Ranges (catching glimpses of Mount Victoria and the Kokoda Track out the aircraft’s port side windows), crossed the Bismarck Archipelago, and traced the south and east coast of New Britain before landing in Rabaul at 11:30. Landing in Rabaul made us feel the expedition had really begun. Our flight was one of only two flights landing in Rabaul that day—the main terminal is one room with one luggage carousel and little else. We gathered our luggage and deposited it on the lorries headed for the ship before joining our buses and guides for an afternoon exploring Rabaul and its environs. Food is always an excellent point of entry for understanding new environments and new cultures, and lunch at the Ralum Country Club offered us a taste of traditional Papua New Guinean foods and local beverages such as PNG’s SP Lager and GoGo Cola. -

Violence and Warfare in the Pre-Contact Caroline Islands

VIOLENCE AND WARFARE IN THE PRE-CONTACT CAROLINE ISLANDS STEPHEN M. YOUNGER University of Hawai‘i The Caroline Islands represent a particularly interesting case for the study of social phenomena in indigenous cultures. Spread out over 2700km, they range from tiny Eauripik, whose area of 0.2km2 is thought by its inhabitants to support a maximum population of 150 persons (Levin and Gorenflo 1994: 117), to Pohnpei, with an area of 334km2 and an estimated pre-contact population of 10,000 (Hanlon 1988: 204). Ecologies range from the isolated volcanic island of Kosrae to many atolls that are within easy sailing reach of their neighbours. The exceptional ability of Carolinean navigators made this one of the most interconnected parts of Oceania. Lessa (1962) argued that frequent canoe voyages led to a homogenisation of culture, but detailed studies of linguistics across the region by Marck (1986) indicate some divergence in dialect (and, one might presume, other cultural elements) when voyaging distances exceeded about 100 miles (161km), i.e., for a canoe journey of more than one day. In this article I examine the relative levels of violence on and between the Caroline Islands. Lessa (1962: 354) noted that “warfare was part of the way of life throughout all of the Carolines, even though the atolls waged it less intensely.” Yet the differences were more than between high islands and atolls. Chuuk (95km2) was perhaps the most violent island in the region (Gladwin and Sarason 1953), but Kosrae (110km2) experienced prolonged periods of relative peace (Peoples 1993). Violence on and between atolls varied between Puluwat, described as the “scourge of this area of the Pacific” (Steager 1971: 61), feared even by the Chuukese, and Namonuito, whose inhabitants vacated their home island when threatened by invasion (Thomas 1978: 32). -

LCSH Section O

O, Inspector (Fictitious character) O-erh-kʾun Ho (Mongolia) O-wee-kay-no Indians USE Inspector O (Fictitious character) USE Orhon River (Mongolia) USE Oowekeeno Indians O,O-dimethyl S-phthalimidomethyl phosphorodithioate O-erh-kʾun River (Mongolia) O-wen-kʻo (Tribe) USE Phosmet USE Orhon River (Mongolia) USE Evenki (Asian people) O., Ophelia (Fictitious character) O-erh-to-ssu Basin (China) O-wen-kʻo language USE Ophelia O. (Fictitious character) USE Ordos Desert (China) USE Evenki language O/100 (Bomber) O-erh-to-ssu Desert (China) Ō-yama (Kanagawa-ken, Japan) USE Handley Page Type O (Bomber) USE Ordos Desert (China) USE Ōyama (Kanagawa-ken, Japan) O/400 (Bomber) O family (Not Subd Geog) O2 Arena (London, England) USE Handley Page Type O (Bomber) Ó Flannabhra family UF North Greenwich Arena (London, England) O and M instructors USE Flannery family BT Arenas—England USE Orientation and mobility instructors O.H. Ivie Reservoir (Tex.) O2 Ranch (Tex.) Ó Briain family UF Ivie Reservoir (Tex.) BT Ranches—Texas USE O'Brien family Stacy Reservoir (Tex.) OA (Disease) Ó Broin family BT Reservoirs—Texas USE Osteoarthritis USE Burns family O Hine Hukatere (N.Z.) OA-14 (Amphibian plane) O.C. Fisher Dam (Tex.) USE Franz Josef Glacier/Kā Roimata o Hine USE Grumman Widgeon (Amphibian plane) BT Dams—Texas Hukatere (N.Z.) Oa language O.C. Fisher Lake (Tex.) O-kee-pa (Religious ceremony) USE Pamoa language UF Culbertson Deal Reservoir (Tex.) BT Mandan dance Oab Luang National Park (Thailand) San Angelo Lake (Tex.) Mandan Indians—Rites and ceremonies USE ʻUtthayān hǣng Chāt ʻŌ̜p Lūang (Thailand) San Angelo Reservoir (Tex.) O.L.