Atolls of the World: Revisiting the Original Checklist

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

This Keyword List Contains Indian Ocean Place Names of Coral Reefs, Islands, Bays and Other Geographic Features in a Hierarchical Structure

CoRIS Place Keyword Thesaurus by Ocean - 8/9/2016 Indian Ocean This keyword list contains Indian Ocean place names of coral reefs, islands, bays and other geographic features in a hierarchical structure. For example, the first name on the list - Bird Islet - is part of the Addu Atoll, which is in the Indian Ocean. The leading label - OCEAN BASIN - indicates this list is organized according to ocean, sea, and geographic names rather than country place names. The list is sorted alphabetically. The same names are available from “Place Keywords by Country/Territory - Indian Ocean” but sorted by country and territory name. Each place name is followed by a unique identifier enclosed in parentheses. The identifier is made up of the latitude and longitude in whole degrees of the place location, followed by a four digit number. The number is used to uniquely identify multiple places that are located at the same latitude and longitude. For example, the first place name “Bird Islet” has a unique identifier of “00S073E0013”. From that we see that Bird Islet is located at 00 degrees south (S) and 073 degrees east (E). It is place number 0013 at that latitude and longitude. (Note: some long lines wrapped, placing the unique identifier on the following line.) This is a reformatted version of a list that was obtained from ReefBase. OCEAN BASIN > Indian Ocean OCEAN BASIN > Indian Ocean > Addu Atoll > Bird Islet (00S073E0013) OCEAN BASIN > Indian Ocean > Addu Atoll > Bushy Islet (00S073E0014) OCEAN BASIN > Indian Ocean > Addu Atoll > Fedu Island (00S073E0008) -

A Report on Some Pontoniinid Shrimps Collected from the Seychelle Islands by the F.R.V. Manihine, 1972, with a Review of The

ft rats, A. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, 59: 89-153. With 30 figures September 1976 A report on some pontoniinid shrimps collected from the Seychelle Islands by the F.R.V. Manihine, 1972, with a review of the Seychelles pontoniinid shrimp fauna | CRUSTACEA LIBRA! crMTTH^O'NT/sII a. j. bruce SI- ^q RETDRN TO vj-xiy East African Marine Fisheries Research Organization, P.O. Box 81651, Mombasa, Kenya* Accepted for publication August 1975 A collection of pontoniinid shrimps, principally from the Islands of Mahe and Praslin, in the western Indian Ocean, is described. Twenty-four species were collected, including two new species, Periclimenes difficilis and Periclimenaeus manihinei. Twenty-two species are considered to be commensals and the hosts of many are identified. The early juvenile stages of several species were collected and are described for the first time. The incidence of regeneration in the second pereiopods is studied in detail in Coralliocaris graminea. The pontoniinid shrimp fauna of the Seychelle Islands is reveiwed and its geographic distribution summarized. Two of the species reported are new records for the Indian Ocean and eight are newly added to the Seychelles fauna. CONTENTS Introduction 90 Species collected by the F.R.V. Manihine 92 Systematic account 93 1. Palaemonella rotumana 93 2. Vir orien talis 95 3. Periclimenes spiniferus 95 4. P. lutescens auct. 98 5. P. diversipes 99 6. P. inornatus 103 7. P. tosaensis 106 8. P. zanzibaricus 107 9. P. mahei 108 10. P. hirsutus 110 11. P. difficilis sp. nov. Ill 12. Anchistus miersi 117 13. -

The Effects of the Cyclones of 1983 on the Atolls of the Tuamotu Archipelago (French Polynesia)

THE EFFECTS OF THE CYCLONES OF 1983 ON THE ATOLLS OF THE TUAMOTU ARCHIPELAGO (FRENCH POLYNESIA) J. F. DUPON ORSTOM (French Institute ofScientific Research for Development through cooperation), 213 Rue Lafayette - 75480 Paris Cedex 10, France Abstract. In the TUAMOTU Archipelago, tropical cyclones may contribute to the destruction as well as to some building up of the atolls. The initial occupation by the Polynesians has not increased the vulnerability of these islands as much as have various recent alterations caused by European influence and the low frequency of the cyclone hazard itself. An unusual series of five cyclones, probably related to the general thermic imbalance of the Pacific Ocean between the tropics struck the group in 1983 and demonstrated this vulnerability through the damage that they caused to the environment and to the plantations and settle ments. However, the natural rehabilitation has been faster than expected and the cyclones had a beneficial result in making obvious the need to reinforce prevention measures and the protection of human settle ments. An appraisal of how the lack of prevention measures worsened the damage is first attempted, then the rehabilitation and the various steps taken to forestall such damage are described. I. About Atolls and Cyclones: Some General Information Among the islands of the intertropical area of the Pacific Ocean, most of the low-lying lands are atolls. The greatest number of them are found in this part of the world. Most atolls are characterized by a circular string of narrow islets rising only 3 to 10 m above the average ocean level. -

Ocean Wave Characteristics in Indonesian Waters for Sea Transportation Safety and Planning

IPTEK, The Journal for Technology and Science, Vol. 26, No. 1, April 2015 19 Ocean Wave Characteristics in Indonesian Waters for Sea Transportation Safety and Planning Roni Kurniawan1 and Mia Khusnul Khotimah2 AbstractThis study was aimed to learn about ocean wave characteristics and to identify times and areas with vulnerability to high waves in Indonesian waters. Significant wave height of Windwaves-05 model output was used to obtain such information, with surface level wind data for 11 years period (2000 to 2010) from NCEP-NOAA as the input. The model output data was then validated using multimission satellite altimeter data obtained from Aviso. Further, the data were used to identify areas of high waves based on the high wave’s classification by WMO. From all of the processing results, the wave characteristics in Indonesian waters were identified, especially on ALKI (Indonesian Archipelagic Sea Lanes). Along with it, which lanes that have high potential for dangerous waves and when it occurred were identified as well. The study concluded that throughout the years, Windwaves-05 model had a magnificent performance in providing ocean wave characteristics information in Indonesian waters. The information of height wave vulnerability needed to make a decision on the safest lanes and the best time before crossing on ALKI when the wave and its vulnerability is likely low. Throughout the years, ALKI II is the safest lanes among others since it has been identified of having lower vulnerability than others. The knowledge of the wave characteristics for a specific location is very important to design, plan and vessels operability including types of ships and shipping lanes before their activities in the sea. -

Annual Report

Darwin Initiative Annual Report Important note: To be completed with reference to the Reporting Guidance Notes for Project Leaders: it is expected that this report will be about 10 pages in length, excluding annexes Submission Deadline: 30 April Project Reference 19-027 Project Title Strengthening the world’s largest Marine Protected Area: Chagos Archipelago Host Country/ies British Indian Ocean Territory (BIOT) Contract Holder Institution Bangor University Partner institutions University of Warwick, Zoological Society of London, FCO BIOT Administration Darwin Grant Value £287,788 Start/end dates of project 2012/13 – 2014/15 Reporting period (eg Apr 2013 2013-2014: Annual Report 2 – Mar 2014) and number (eg Annual Report 1, 2, 3) Project Leader name Dr John R Turner Project website Chagos Environment Outreach Project: http://www.zsl.org/conservation/regions/africa/chagos- coral/chagos-community,1915,AR.html http://www.zsl.org/regions/uk-and-overseas-territories/chagos- archipelago Scientific Expedition 2014: http://chagos-trust.org/2014-biot- expedition Report author(s) and date Dr John Turner, Prof Charles Sheppard, Dr Heather Koldewey, Rebecca Short and Audrey Blancart contributed to report and/or annexes. June 2014. Project Goal: To strengthen the Chagos Marine Protected Area by providing scientific knowledge for effective management, and develop a strategy that engages the support of potential stakeholders through outreach, education and engagement. The legacy will be sound management and increased value of what is currently the world’s largest no-take Marine Protected Area and a unique and globally important reference site. Location: The Chagos archipelago is situated in the middle of the Indian Ocean at the southernmost end of the Laccadive-Chagos ridge. -

IOM Micronesia

IOM Micronesia Federated States of Micronesia Republic of the Marshall Islands Republic of Palau Newsletter, July 2018 - April 2019 IOM staff Nathan Glancy inspects a damaged house in Chuuk during the JDA. Credit: USAID, 2019 Typhoon Wutip Destruction Typhoon Wutip passed over Pohnpei, Chuuk, and Yap States, FSM between 19 and 22 February with winds of 75–80 mph and gusts of up to 100 mph. Wutip hit the outer islands of Chuuk State, including the ‘Northwest’ islands (Houk, Poluwat, Polap, Tamatam and Onoun) and the ‘Lower and ‘Middle’ Mortlocks islands, as well as the outer islands of Yap (Elato, Fechailap, Lamotrek, Piig and Satawal) before continuing southwest of Guam and slowly dissipating by the end of February. FSM President, H.E. Peter M. Christian issued a Declaration of Disaster on March 11 and requested international assistance to respond to the damage caused by the typhoon. Consistent with the USAID/FEMA Operational Blueprint for Disaster Relief and Reconstruction in the Federated States of Micronesia (FSM) and the Republic of the Marshall Islands (RMI), a Joint Damage Assessment (JDA) was carried out by representatives of USAID, OFDA, FEMA and the Government of FSM from 18 March to 4 April, with assistance from IOM. The JDA assessed whether Wutip damage qualifies for a US Presidential Disaster Declaration. The JDA found Wutip had caused damage to the infrastructure and agricultural production of 30 islands, The path of Typhoon Wutip Feb 19-22, 2019. Credit: US JDA, 2019. leaving 11,575 persons food insecure. Response to Typhoon Wutip IOM, with the support of USAID/OFDA, has responded with continued distributions of relief items stored in IOM warehouses such as tarps, rope and reverse osmosis (RO) units to affected communities on the outer islands of Chuuk, Yap and Pohnpei states. -

Mangroves and Coral Reefs: David Stoddart and the Cambridge Physiographic Tradition Colin D

University of Wollongong Research Online Faculty of Science, Medicine and Health - Papers: Faculty of Science, Medicine and Health Part B 2018 Mangroves and coral reefs: David Stoddart and the Cambridge physiographic tradition Colin D. Woodroffe University of Wollongong, [email protected] Publication Details Woodroffe, C. D. (2018). Mangroves and coral reefs: David Stoddart and the Cambridge physiographic tradition. Atoll Research Bulletin, 619 121-145. Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] Mangroves and coral reefs: David Stoddart and the Cambridge physiographic tradition Abstract Mangroves are particularly extensive on sheltered, macrotidal, muddy tropical coastlines, but also occur in association with coral reefs. Reefs attenuate wave energy, in some locations enabling the accretion of fine calcareous sediments which in turn favour establishment of seagrasses and mangroves. Knowledge of the distribution and ecology of both reefs and mangroves increased in the first half of the 20th century. J Alfred Steers participated in the Great Barrier Reef Expedition in 1928, and developed an interest in the geomorphological processes by which islands had formed in this setting. It became clear that many mangrove forests showed a zonation of species and some researchers inferred successional changes, even implying that reefs might transition through a mangrove stage, ultimately forming land. Valentine Chapman studied the ecology of mangroves, and Steers and Chapman described West Indian mangrove islands in the 1940s during the University of Cambridge expedition to Jamaica. These studies provided the background for David Stoddart's participation in the Cambridge Expedition to British Honduras and his PhD examination of three Caribbean atolls. -

ISO Country Codes

COUNTRY SHORT NAME DESCRIPTION CODE AD Andorra Principality of Andorra AE United Arab Emirates United Arab Emirates AF Afghanistan The Transitional Islamic State of Afghanistan AG Antigua and Barbuda Antigua and Barbuda (includes Redonda Island) AI Anguilla Anguilla AL Albania Republic of Albania AM Armenia Republic of Armenia Netherlands Antilles (includes Bonaire, Curacao, AN Netherlands Antilles Saba, St. Eustatius, and Southern St. Martin) AO Angola Republic of Angola (includes Cabinda) AQ Antarctica Territory south of 60 degrees south latitude AR Argentina Argentine Republic America Samoa (principal island Tutuila and AS American Samoa includes Swain's Island) AT Austria Republic of Austria Australia (includes Lord Howe Island, Macquarie Islands, Ashmore Islands and Cartier Island, and Coral Sea Islands are Australian external AU Australia territories) AW Aruba Aruba AX Aland Islands Aland Islands AZ Azerbaijan Republic of Azerbaijan BA Bosnia and Herzegovina Bosnia and Herzegovina BB Barbados Barbados BD Bangladesh People's Republic of Bangladesh BE Belgium Kingdom of Belgium BF Burkina Faso Burkina Faso BG Bulgaria Republic of Bulgaria BH Bahrain Kingdom of Bahrain BI Burundi Republic of Burundi BJ Benin Republic of Benin BL Saint Barthelemy Saint Barthelemy BM Bermuda Bermuda BN Brunei Darussalam Brunei Darussalam BO Bolivia Republic of Bolivia Federative Republic of Brazil (includes Fernando de Noronha Island, Martim Vaz Islands, and BR Brazil Trindade Island) BS Bahamas Commonwealth of the Bahamas BT Bhutan Kingdom of Bhutan -

A Companion to Contemporary Documentary Filn1

A Companion to Contemporary Documentary Filn1 Edited by Alexandra Juhasz and Alisa Lebow WI LEY Blackwell 2 o ,�- This edition first published 2015 © 2015 John Wiley & Sons, Inc, excepting Chapter 1 © 2014 by the Regents of the University of Minnesota and Chapter 19 © 2007 Wayne State University Press Registered Office John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, UK Contents Editorial Offices 350 Main Street, Malden, MA 02148-5020, USA 9600 Garsington Road, Oxford, OX4 2DQ, UK The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, UK For details of our global editorial offices,for customer services, and for informationabout how to apply for permission to reuse the copyright material in this book please see our website at www.wiley.com/wiley-blackwell. The right of Alexandra Juhasz and Alisa Lebow to be identifiedas the authors of the editorial material in this work has been asserted in accordance with the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, except as permitted by the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, without the prior permission of the publisher. Wiley also publishes its books in a variety of electronic formats. Some content that appears in print Notes on Contributors ix may not be available in electronic books. Introduction: A World Encountered 1 Designations used by companies to distinguish their products are often claimed as trademarks. All Alexandra Juhasz and Alisa Lebow brand names and product names used in this book are trade names, service marks, trademarks or registered trademarks of their respective owners. -

Secret Seychelles Islands with Ponant Aboard Le Jacques Cartier

SECRET SEYCHELLES ISLANDS WITH PONANT ABOARD LE JACQUES CARTIER Embark with PONANT on an expedition cruise to discover the most beautiful islands of the Seychelles. This 13-day itinerary aboard Le Jacques-Cartier will be an opportunity to discover little-known places of breathtaking natural beauty and an original fauna and flora. Leaving from Victoria, the archipelago’s capital, fall under the spell of the idyllic landscapes, with their exceptional flora and fauna. In Praslin, don’t miss the chance to visit the Vallée de Mai Nature Reserve. There you will find sea coconuts, gigantic fruits with a very evocative shape, nicknamed the “love nut”. You will discover the island of Aride, an unspoiled delight of the Indian Ocean, home to thousands of birds including some endemic species. During your cruise, you will have many opportunities to dive or snorkel, notably in Poivre, Assomption, Astove, and at the heart of the sublime coral reef in the Alphonse lagoon. Another highlight of your trip will be the port of call at Cosmoledo. This magnificent atoll owes its nickname, the Galapagos of the Indian Ocean, to the beauty of its unique underwater world. Diving in this paradise lagoon becomes an extraordinary experience. Before you return to Mahé, Le Jacques-Cartier will chart a course for the coral island of Desroches and the sublime beaches of La Digue, some of the most renowned of the Seychelles. The encounters with the wildlife described above illustrate possible experiences ITINERARY only and cannot be guaranteed. Day 1 VICTORIA, MAHÉ Discover Mahé, the main island of the Seychelles and also the largest of the archipelago, home to the capital, Victoria. -

The Case of Ahe and Takaroa Atolls and Implications for the Cultured Pearl Industry

Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science 182 (2016) 243e253 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ecss Revisiting wild stocks of black lip oyster Pinctada margaritifera in the Tuamotu Archipelago: The case of Ahe and Takaroa atolls and implications for the cultured pearl industry * Serge Andrefou et€ a, , Yoann Thomas a, 1, Franck Dumas b,Cedrik Lo c a UMR-9220 ENTROPIE, Institut de Recherche pour le Developpement, UniversitedelaReunion, CNRS, Noumea, New Caledonia b Ifremer, DYNECO/DHYSED, Plouzane, France c Direction des Ressources Marines et Minieres, Papeete, Tahiti, French Polynesia article info abstract Article history: Spat collecting of the black lip oyster (Pinctada margaritifera) is the foundation of cultured black pearl Received 30 June 2015 production, the second source of income for French Polynesia. To understand spat collecting temporal Received in revised form and spatial variations, larval supply and its origin need to be characterized. To achieve this, it is necessary 14 May 2016 to account for the stock of oysters, its distribution and population characteristics (size distribution, sex- Accepted 19 June 2016 ratio). While the farmed stock in concessions can be easily characterized, the wild stock is elusive. Here, Available online 20 June 2016 we investigate the distribution and population structure of the wild stock of Ahe and Takaroa atolls using fine-scale bathymetry and in situ census data. Stocks were surprisingly low (~666,000 and ~1,030,000 Keywords: Invertebrate population oysters for Ahe and Takaroa respectively) considering these two atolls have both been very successful Aquaculture spat collecting atolls in the past. -

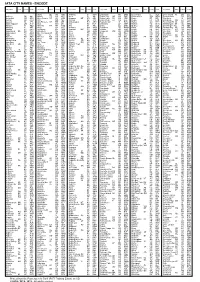

Iata City Names - Encode

IATA CITY NAMES - ENCODE City name State Country Code City name State Country Code City name State Country Code City name State Country Code City name State Country Code City name State Country Code Alpha QL AU ABH Aribinda BF XAR Bakelalan MY BKM Beersheba IL BEV Block Island RI US BID Aalborg DK AAL Alpine TX US ALE Arica CL ARI Baker City OR US BKE Befandriana MG WBD Bloemfontein ZA BFN Aalesund NO AES Alroy Downs NT AU AYD Aripuana MT BR AIR Baker Lake NU CA YBK Beica ET BEI Blonduos IS BLO Aarhus DK AAR Alta NO ALF Arkalyk KZ AYK Bakersfield CA US BFL Beida LY LAQ Bloodvein MB CA YDV Aasiaat GL JEG Alta Floresta MT BR AFL Arkhangelsk RU ARH Bakkafjordur IS BJD Beihai CN BHY Bloomfield Ri QL AU BFC Aba/Hongyuan CN AHJ Altai MN LTI Arlit NE RLT Bakouma CF BMF Beihan YE BHN Bloomington IN US BMG Abadan IR ABD Altamira PA BR ATM Arly BF ARL Baku AZ BAK Beijing CN BJS Bloomington-NIL US BMI Abaiang KI ABF Altay CN AAT Armenia CO AXM Balakovo RU BWO Beira MZ BEW Blubber Bay BC CA XBB Abakan XU ABA Altenburg DE AOC Armidale NS AU ARM Balalae SB BAS Beirut LB BEY Blue Bell PA US BBX Abbotsford BC CA YXX Altenrhein CH ACH Arno MH AMR Balgo Hill WA AU BQW Bejaia DZ BJA Bluefield WV US BLF Abbottabad PK AAW Alto Rio Seng CB AR ARR Aroa PG AOA Bali CM BLC Bekily MG OVA Bluefields NI BEF Abbs YE EAB Alton IL US ALN Arona SB RNA Bali PG BAJ Belaga MY BLG Blumenau SC BR BNU Abeche TD AEH Altoona PA US AOO Arorae KI AIS Balikesir TR BZI Belem PA BR BEL Blythe CA US BLH Abemama KI AEA Altus OK US LTS Arrabury QL AU AAB Balikpapan ID BPN Belfast GB