How to Explain This and the Construction Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Poetic Reformulations of Dwelling in Jo Shapcott, Alice Oswald, and Lavinia Greenlaw

Homecomings: Poetic reformulations of dwelling in Jo Shapcott, Alice Oswald, and Lavinia Greenlaw Janne Stigen Drangsholt, University of Stavanger Abstract In the study The Last of England?, Randall Stevenson refers to the idea of landscape as “the mainstay of poetic imagination” (Stevenson 2004:3). With the rise of the postmodern idiom, our relationship to the “scapes” that surround us has become increasingly problematic and the idea of place is also increasingly deferred and dis- placed. This article examines the relationship between self and “scapes” in the poetries of Jo Shapcott, Alice Oswald and Lavinia Greenlaw, who are all concerned with various “scapes” and who present different, yet connected, strategies for negotiating our relationships to them. Keywords: shifting territories; place; contemporary poetry; postmodernity In The Last of England?, Randall Stevenson points to how the mid- century renunciation of empire was followed by changes that need to be understood primarily in terms of loss. Each of these losses are conceived as marking the last of a certain kind of England, he says, and while another England gradually emerged, this was an England less unified by tradition and more open in outlook, lifestyle, and culture, in short, a place characterised by factors that render it more difficult to define (cf. Stevenson 2004: 1-10). Along with these losses in terms of national character, Stevenson holds, the English landscape also seemed to be increasingly imperilled. While this landscape had traditionally been “the mainstay of poetic imagination” it now seemed in danger of disappearing, as signalled in Philip Larkin’s poem “Going, Going”, where he laments an “England gone, / The shadows, the meadows, the lanes” (Stevenson 2004: 3). -

Papers of John L. (Jack) Sweeney and Máire Macneill Sweeney LA52

Papers of John L. (Jack) Sweeney and Máire MacNeill Sweeney LA52 Descriptive Catalogue UCD Archives School of History and Archives archives @ucd.ie www.ucd.ie/archives T + 353 1 716 7555 F + 353 1 716 1146 © 2007 University College Dublin. All rights reserved ii CONTENTS CONTEXT Biographical history iv Archival history v CONTENT AND STRUCTURE Scope and content v System of arrangement vi CONDITIONS OF ACCESS AND USE Access xiv Language xiv Finding-aid xiv DESCRIPTION CONTROL Archivist’s note xiv ALLIED MATERIALS Allied Collections in UCD Archives xiv Related collections elsewhere xiv iii Biographical History John Lincoln ‘Jack’ Sweeney was a scholar, critic, art collector, and poet. Born in Brooklyn, New York, he attended university at Georgetown and Cambridge, where he studied with I.A. Richards, and Columbia, where he studied law. In 1942 he was appointed curator of Harvard Library’s Poetry Room (established in 1931 and specialising in twentieth century poetry in English); curator of the Farnsworth Room in 1945; and Subject Specialist in English Literature in 1947. Stratis Haviaras writes in The Harvard Librarian that ‘Though five other curators preceded him, Jack Sweeney is considered the Father of the Poetry Room …’. 1 He oversaw the Poetry Room’s move to the Lamont Library, ‘establishing its philosophy and its role within the library system and the University; and he endowed it with an international reputation’.2 He also lectured in General Education and English at Harvard. He was the brother of art critic and museum director, James Johnson Sweeney (Museum of Modern Art, New York; Solomon R. -

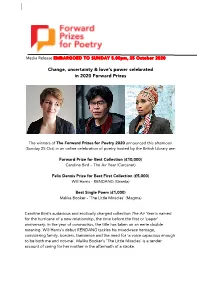

Change, Uncertainty & Love's Power Celebrated in 2020 Forward Prizes

Media Release EMBARGOED TO SUNDAY 5.00pm, 25 October 2020 Change, uncertainty & love’s power celebrated in 2020 Forward Prizes The winners of The Forward Prizes for Poetry 2020 announced this afternoon (Sunday 25 Oct) in an online celebration of poetry hosted by the British Library are: Forward Prize for Best Collection (£10,000) Caroline Bird – The Air Year (Carcanet) Felix Dennis Prize for Best First Collection (£5,000) Will Harris - RENDANG (Granta) Best Single Poem (£1,000) Malika Booker - ‘The Little Miracles’ (Magma) Caroline Bird’s audacious and erotically charged collection The Air Year is named for the hurricane of a new relationship, the time before the first or ‘paper’ anniversary: in the year of coronavirus, the title has taken on an eerie double meaning. Will Harris’s debut RENDANG tackles his mixed-race heritage, considering family, borders, transience and the need for ‘a voice capacious enough to be both me and not-me’. Malika Booker’s ‘The Little Miracles’ is a tender account of caring for her mother in the aftermath of a stroke. 2 The chair of the 2020 jury, writer, critic and cultural historian Alexandra Harris, commented: ‘We are thrilled to celebrate three winning poets whose finely crafted work has the protean power to change as it meets new readers.’ The Forward Prize for Poetry, founded by William Sieghart and run by the charity Forward Arts Foundation, are the most prestigious awards for new poetry published in the UK and Ireland, and have been sponsored since their launch in 1992 by the content marketing agency, Bookmark (formerly Forward Worldwide). -

Poetry Anthology (Post-2000)

FHS English Department ENGLISH LITERATURE Poems of the Decade: Forward Poetry Anthology (Post-2000) Assessment: Paper 3 Poetry Section A One question from a choice of two, comparing an unseen poem with a named poem from the anthology (30 marks) 1 hour 7 minutes AOs AO1 Articulate informed, personal and creative responses to literary texts, using associated concepts and terminology, and coherent, accurate written expression AO2 Analyse ways in which meanings are shaped in literary texts Terminology *A full glossary of terms can be found on the S Drive/English/KS5/Literature/Poetry Glossary Overview of Poems, Poets and Themes EAT ME CHAINSAW VERSUS THE PAMPAS MATERIAL HISTORY AN EASY PASSAGE Patience Agbabi GRASS Ros Barber John Burnside Julia Copus Simon Armitage This poem looks at the idea of a This poem considers the relationship This poem considers the transition be- This poem considers the significance of This poem centres around the journey ‘feeder’ role within a relationship, between man made, physical objects, tween childhood and adulthood, and historical events, particularly the World of a young girl sneaking into her house, using an unusual structure of tercet with nature and the natural world, spe- the narrator’s nostalgia for a less con- Trade Center attacks in September presented in a surreal format which stanzas and a notable semantic cifically using the symbolism of a chain- sumer-driven world through the de- 2001. Burnside is a Scottish poet, born helps to create a distinctive narrative field. Agbabi is a performance poet saw to show man’s interaction. scription of a traditional handker- in 1955 in Fife. -

Barbarian Masquerade a Reading of the Poetry of Tony Harrison And

1 Barbarian Masquerade A Reading of the Poetry of Tony Harrison and Simon Armitage Christian James Taylor Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Leeds School of English August 2015 2 The candidate confirms that the work submitted is his own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation fro m the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement The right of Christian James Taylor to be identified as Author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. © 2015 The University of Leeds and Christian James Taylor 3 Acknowledgements The author hereby acknowledges the support and guidance of Dr Fiona Becket and Professor John Whale, without whose candour, humour and patience this thesis would not have been possible. This thesis is d edicat ed to my wife, Emma Louise, and to my child ren, James Byron and Amy Sophia . Additional thanks for a lifetime of love and encouragement go to my mother, Muriel – ‘ never indifferent ’. 4 Abstract This thesis investigates Simon Armitage ’ s claim that his poetry inherits from Tony Harrison ’ s work an interest in the politics o f form and language, and argues that both poets , although rarely compared, produce work which is conceptually and ideologically interrelated : principally by their adoption of a n ‘ un - poetic ’ , deli berately antagonistic language which is used to invade historically validated and culturally prestigious lyric forms as part of a critique of canons of taste and normative concepts of poetic register which I call barbarian masquerade . -

No Italian Translation

MASK OF BYRON DISPLAYS NEW FACE October 5, 2004 A WAX carnival mask worn by Lord Byron at the height of the great poet's passionate affair with a young Italian countess in the early 19th century goes on display in Rome today after a delicate restoration. The mask, worn by Byron at a Ravenna carnival in 1820, was given to the Keats-Shelley Memorial House 40 years ago. But Catherine Payling, 33, director of the museum, said she was shocked by its deterioration when taking over 15 months ago. The Keats-Shelley house, next to the Spanish Steps, where Keats died in 1821, contains memorabilia associated with Keats, Shelley and Byron, all of whom lived in Italy at the height of the Romantic movement. Byron had left England in 1816 after a series of affairs and a disastrous year-long marriage, to join a brilliant group of English literary exiles that included Shelley and his wife, Mary. In the spring of 1819, Byron met Countess Teresa Guiccioli, who was only 20 and had been married for a year to a rich and eccentric Ravenna aristocrat three times her age. The encounter, he said later, "changed my life", and from then on he confined himself to "only the strictest adultery". Byron gave up "light philandering" to live with Teresa, first in the Palazzo Guiccioli in Ravenna - conducting the affair under the nose of the count - and then in Pisa after the countess had obtained a separation by papal decree. In his letters to John Murray, his publisher, Byron said that carnivals and balls were "the best thing about Ravenna, when everybody runs mad for six weeks", and described wearing the mask - which originally sported a thick beard - to accompany the countess to the carnival. -

2018 Forward Prizes for Poetry Announce “Urgent, Engaged and Inspirational” Shortlists

MEDIA RELEASE | IMMEDIATE RELEASE, THURSDAY 24 MAY 2018 2018 FORWARD PRIZES FOR POETRY ANNOUNCE “URGENT, ENGAGED AND INSPIRATIONAL” SHORTLISTS Nuclear stand-off, new-born lambs, sex, Hollywood blockbusters, and addiction - Britain’s most coveted poetry awards, the Forward Prizes for Poetry, have today announced shortlists dominated by “urgent, engaged and inspirational” voices tackling complex subjects with brio. The chair of the 2018 jury, the writer, critic and broadcaster Bidisha, said: “In reading for this year’s Forward Prizes, the other judges and I discovered an art form that is in roaring health. We read countless collections full of wonder and possibility, light but not trivial, serious but not depressing, lushly emotional but not sentimental, frequently witty and capable of great craft and zingy modernity. “Our shortlists represent the stunning variety and breadth of poetry today, with contemporary international voices that are urgent, engaged and inspirational.” The Forward Prizes for Poetry celebrate the best new poetry published in the British Isles. They honour both established poets and emerging writers with three distinct awards: Best Collection, Best First Collection and Best Single Poem. They are sponsored by Bookmark Content, the content and communications company. The 2018 Forward Prize for Best Collection (£10,000) Vahni Capildeo – Venus as a Bear (Carcanet) Toby Martinez de las Rivas – Black Sun (Faber) J.O. Morgan – Assurances (Cape) Danez Smith – Don’t Call Us Dead (Chatto) Tracy K. Smith – Wade in the Water (Penguin) -

Mapping and Twentieth-Century American Poetry

The Dissertation Committee for Alba Rebecca Newmann certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: “Language is not a vague province”: Mapping and Twentieth -Century American Poetry Committee: ________________________ ______ Wayne Lesser, Supervisor ______________________________ Thomas Cable, Co -Supervisor ______________________________ Brian Bremen ______________________________ Mia Carter ______________________________ Nichole Wiedemann “Language is not a vague province”: Mapping and Twentieth -Century American Poetry by Alba Rebecca Newmann, B.A.; M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin May 2006 Acknowledgements I wish to express my appreciation to each of my dissertation committee members, Wayne, Tom, Mia, Brian, and Nichole, for their insight and encouragement throughout the writing of this document. My family has my heartfelt thanks as well , for their unflagging support in this, and all my endeavors. To my lovely friends and colleagues at the University of Texas —I am grateful to have found myself in such a vibrant and collegial community ; it surely facilitated my completion of this project . And, finally, to The Flightpath, without which, many things would be different. iii “Language is not a vague province”: Mapping and Twentieth -Century American Poetry Publication No. _________ Alba Rebecca Newmann, Ph.D. The University of Texas at Austin, 2006 Supervisors: Wayne Lesser and Thomas Cable In recent years, the terms “mapping” and “cartography” have been used with increasing frequency to describe literature engaged with place. The limitation of much of this scholarship its failure to investigate how maps themselves operate —how they establish relationships and organize knowledge. -

The Poetry of Paul Celan and Seamus Heaney and the Poetic

Coyle, Derek (2002) 'Out to an other side':the poetry of Paul Celan and Seamus Heaney and the poetic challenge to post-modern discussions of absence and presence in the context of theological and philosophical conceptions of language and artistic production. PhD thesis. http://theses.gla.ac.uk/1765/ Copyright and moral rights for this thesis are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Glasgow Theses Service http://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] Thesis: "Out to an Other Sideý- The poetry of Paul Celan and Seamus Heaney and the poetic, challenge to post-modem discussions of absence and presence in the context of theological and philosophical conceptions of language and artistic production Derek CoYle For the Ph. D Degree University of Glasgow Faculty of Divinity July 2002 Abstract Martin Heideggerin 'The Origin of the Work of Art' seeksto approachthe self- subsistentnature of art. The Greek Temple opensup a spacewithin which our Being may dwell. It is the site of human civilization and religion, and of our capacityto dwell within abstractionslike peace,justice, truth and representation.Art breaksopen a new place and presentsthings in a fresh light. -

Poetry from Britain and Ireland Since 1945

The Penguin Book of Poetry from Britain and Ireland since 1945 EDITED BY SIMON ARMITAGE AND ROBERT CRAWFORD VIKING CONTENTS Introduction xix EDWIN MUIR 1887-1959 The Interrogation 1 The Annunciation 2 The Horses 3 HUGH MACDIABMID 1892-1978 Crystals Like Blood 5 To a Friend and Fellow-Poet 6 DAVID JONES 1895-1974 from The Sleeping Lord 7 ROBERT GRAVES 1895-1985 The White Goddess 9 Apple Island 10 Surgical Ward: Men 11 AUSTIN CLARKE 1896-1974 from Eighteenth Century Harp Songs (Mabel Kelly) 12 RUTH PITTER 1897—1992 Old Nelly's Birthday 13 BASIL BUNTING 1900-1985 from Briggflatts 15 STEVIE SMITH 1902-1971 Do Take Muriel Out 20 Not Waving but Drowning 21 The Jungle Husband 22 Piggy to Joey 22 PATRICK KAVANAGH 1904—1967 A Christmas Childhood 23 The Long Garden 25 I vi | Contents JOHN BETJEMAN 1906-1984 A-Subaltern's Love-Song 26 I. M. Walter Ramsden ob. March 26, 1947, Pembroke College, Oxford 28 Executive 29 Louis MACNEICE 1907-1963 All Over Again 30 Soap Suds 31 The Suicide 31 The Taxis 32 W. H. AUDEN 1907-1973 The Fall of Rome 33 The Shield of Achilles 34 First Things First 36 In Praise of Limestone 37 JOHN HEWITT 1907-1987 I Write For ... 40 The Scar 41 KATHLEEN RAINE 1908— Air 42 The Pythoness 42 ROBERT GARIOCH 1909-1981 The Wire 43 NORMAN MACCAIG 1910—1996 Summer farm 48 July evening 49 Aunt Julia 50. Toad 51 Small boy 52 SOMHAIRLE MACGILL-EAIN/SORLEY MACLEAN 1911-1996 Soluis/Lights 53 Hallaig/Hallaig 54 A' Bheinn air Chall/The Lost Mountain 58 ROY FULLER 1912—1991 1948 60 Contents | vii | GEORGE BARKER 1913-1991 On a Friend's Escape from Drowning off the Norfolk Coast 61 from Villa Stellar 62 R. -

<Insert Cover>

` An Chomhairle Ealaíon An Dara Tuarascáil Bhliantúil is Tríocha maille le Cuntais don bhliain dar chríoch 31ú Nollaig 1983. Tíolachadh don Rialtas agus leagadh faoi bhráid gach T1 den Oireachtas de bhun Altanna 6(3) agus 7(1) den Acht Ealaíon 1951 (P1.2619). Thirty-second Annual Report and Accounts for the year ended 31st December 1983. Presented to the Government and laid before each House of the Oireachtas pursuant to Sections 6(3) and 7(1) of the Arts Act, 1951 ISBN 0 906627 06 0 ISSN 0790-1593 Cover. Photograph by Jaimie Blandford of The Slide File, of the gold tore symbol of Aosdána. The torc, which was made by Pat Flood, is worn by the Saoi. Members (Until December 1983) (From January 1984) James White, Chairman Mairtin McCullough, Chairman Robert Ballagh John Banville Kathleen Barrington Vivienne Bogan Brian Boydell Breandán Breathnach Máire de Paor David Byers Andrew Devane Patrick Dawson Brian Friel Máire de Paor Arthur Gibney Bríd Dukes J. B. Kearney Vincent Ferguson Proinsias MacAonghusa Mairéad Furlong Patrick J. Murphy Garry Hynes Donald Potter Barry McGovern Nóra Relihan Patrick J. Murphy Michael Scott Éilís O’Connell Richard Stokes Seán Ó Mordha T. J. Walsh Michael Smith James Warwick Michael Taylor Staff Director Adrian Munnelly (from July) Director Colm Ó Briain (until July) Drama and Dance Officer Arthur Lappin Opera and Music Officer Marion Creely Traditional Music and Regional Development Officer Paddy Glackin Education and Community Arts Officer Adrian Munnelly (until July) Literature and Combined Arts Officer Laurence Cassidy Visual Arts Officer/Grants Medb Ruane Visual Arts Officer I Exhibitions Patrick Murphy Finance Officer David McConnell Administration Research and Film Officer Phelim Donlon Executive Assistant Nuala O'Byrne Secretarial Assistants Patricia Callaly Antoinette Dawson Sheilah Harris Kevin Healy Patricia Moore Bernadette O'Leary Suzanne Quinn Receptionist Kathryn Cahille 70 Merrion Square, Dublin 2. -

Incorporating Writing Issue 1 Volume 4 Contact [email protected] ------Incorporating Writing Is an Imprint of the Incwriters Society (UK)

1 www.incwriters.com Incorporating Writing Issue 1 Volume 4 Contact [email protected] ---------------------------------------------------- Incorporating Writing is an imprint of The Incwriters Society (UK). The magazine is managed by an editorial team independent of The Society's Constitution. Nothing in this magazine may be reproduced in whole or part without permission of the publishers. We cannot accept responsibility for unsolicited manuscripts, reproduction of articles, photographs or content. Incorporating Writing has endeavoured to ensure that all information inside the magazine is correct, however prices and details are subject to change. Individual contributors indemnify Incorporating Writing, The Incwriters Society (UK) against copyright claims, monetary claims, tax payments / NI contributions, or any other claims. This magazine is produced in the UK © The Incwriters Society (UK) 2004 ---------------------------------------------------- In this issue: Editorial: Beginnings and Endings Making Snow Angels With Michael: An Interview with Eva Salzman Interview with Ian Rankin Taking the Leap: An interview with Lucy English Moving Up The Bench Alien: Life in Asia The Screaming Rock - A poetry project for Ireland (and me) Making Connections – thoughts of a literary magazine editor Be Judged or Be Damned Day in the life of a guidebook writer She is Reviews ---------------------------------------------------- Beginnings and Endings Editorial by Andrew Oldham The Incwriters Society (UK) is passing into a new phase, with plans to open a chapter in the States in 2005 and bring grass roots promotion and poetry to wider audience, our reach now extends across several continents; projects include the sponsoring of the poet, Dave Wood, in his recent Ireland trip (see the new regular column in this edition) and bringing the Suffolk County (NY) Poet Laureate, George Wallace to the UK this November, part of his wider USA and European tour (see George's latest article).